Rondo Hatton

Rondo Hatton | |

|---|---|

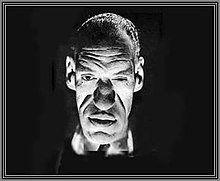

Hatton's acromegalic features made him a Hollywood horror film icon | |

| Born | April 22, 1894 Hagerstown, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died | February 2, 1946 (aged 51) |

| Resting place | American Legion Cemetery, Tampa, Florida |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, actor |

| Years active | 1927–1946 (actor) |

| Spouses | Elizabeth Immell James

(m. 1926; div. 1930)Mabel Housh (m. 1934–1946) |

Rondo Hatton (April 22, 1894 – February 2, 1946)[1] was an American journalist and actor. After writing for The Tampa Tribune, Hatton found a career in film due to his unique facial features, which were the result of acromegaly. He headlined horror films with Universal Studios near the end of his life, earning him a reputation as a cult icon.

Early years

[edit]Hatton was born in the Kee Mar College girls' infirmary in Hagerstown, Maryland.[2][3] The family moved several times during Hatton's youth before settling in Tampa, Florida.[4] He starred in track and football at Hillsborough High School and was voted Handsomest Boy in his class his senior year.[4]

In Tampa, Hatton worked as a sportswriter for The Tampa Tribune. He continued working as a journalist until after World War I, when the symptoms of acromegaly developed. Acromegaly distorted the shape of Hatton's head, face, and extremities in a gradual but consistent process. He eventually became severely disfigured by the disease.[5] Because the symptoms developed in adulthood (as is common with the disorder), the disfigurement was incorrectly attributed later by film studio publicity departments to elephantiasis resulting from exposure to a German mustard gas attack during service in World War I.[6] Hatton served in combat and served on the Pancho Villa Expedition along the Mexican border and in France during World War I with the United States Army,[2] from which he was discharged due to his illness.

Career

[edit]Director Henry King noticed Hatton when he was working as a reporter with The Tampa Tribune covering the filming of Hell Harbor (1930) and hired him for a small role.[5] After some hesitation, Hatton moved to Hollywood in 1936 to pursue a career playing similar, often uncredited, bit and extra roles. His most notable of these was as a contestant-extra in the "ugly man competition" (which he loses to a heavily made up Charles Laughton) in the RKO production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame. He had another supporting-character role as Gabe Hart, a member of the lynch mob in the 1943 film of The Ox-Bow Incident.

Universal Studios used Hatton's unusual features to promote him as a horror star after he played the part of The Hoxton Creeper (aka The Hoxton Horror) in the studio's ninth Sherlock Holmes film, The Pearl of Death (1944). He made two films playing "the Creeper", House of Horrors and The Brute Man, which were both filmed in 1945 but not released until after his death in 1946.[7]

Death

[edit]Around Christmas 1945, Hatton suffered a series of heart attacks, a direct result[8] of his acromegalic condition.[4][7] On February 2, 1946, he suffered a fatal heart attack at his home on South Tower Drive in Los Angeles.[4] His body was transported to Florida and interred at the American Legion Cemetery in Tampa.[9][10]

Legacy

[edit]Hatton's name – and face – have become recurring humorous motifs in popular culture. In season 6, episode 4 of the 1970s television series The Rockford Files ("Only Rock-n-Roll Will Never Die, part 1"), Jim Rockford, exasperated at a friend who dismisses himself as unattractive, exclaims "You're no Rondo Hatton!" Hatton's physical likeness inspired the Lothar character in Dave Stevens's 1980s Rocketeer Adventure Magazine stories, and in Disney's 1991 film version, The Rocketeer, in which the character is played by actor Tiny Ron in prosthetic make-up.

The Scooby Doo cartoon series character The Creeper, who vaguely resembles Frankenstein's Monster, is likely based on Universal Studios' own "Creeper" from the 1946 film The House of Horrors, who was portrayed by Rondo Hatton, with Scooby Doo's Creeper seemingly being a caricature of Rondo in terms of hand size and facial features.

The 2000 AD comic book character Judge Dredd, who is rarely seen without his helmet, used "face-changing technology" to make himself look like Hatton in issue 52 (February 18, 1978) – the first time the character's face was shown unobscured. The name "Rondo Hatton" was also in a list of suspects obtained by Dredd during the case.[11] As the artist Brian Bolland revealed in an interview with David Bishop: "The picture of Dredd's face – that was a 1940s actor called Rondo Hatton. I've only seen him in one film."[12] Additionally, the character The Creep in the Dark Horse Presents comic-book series strongly resembled Hatton.

Hatton is regularly name-checked in the novels of Robert Rankin, often referred to as "the now-legendary Rondo Hatton" and credited as appearing in films that are either fictional, or in which he clearly had no part, such as the Carry On films. Rankin's references to Hatton routinely occur in the form of "he had a Rondo Hatton" (hat on). Another namecheck occurs in Rafi Zabor's PEN/Faulkner-award-winning 1998 novel The Bear Comes Home, where the name is used as a nickname for good-natured but unrefined minor character Tommy Talmo. In the 2004 Stephen King novel, The Dark Tower VII, a character is described as looking "like Rondo Hatton, a film actor from the 1930s, who suffered from acromegaly and got work playing monsters and psychopaths". In the 1991 movie The Rocketeer, actor Tiny Ron Taylor, playing Nazi henchman Lothar, is made up with prosthetics to look like Hatton. The episode of Doctor Who entitled "The Wedding of River Song" features Mark Gatiss as a character whose appearance (achieved through prosthetics) is based on Hatton's, credited under the pseudonym Rondo Haxton for his performance.[13]

A documentary being produced in 2017, Rondo and Bob,[14][15] and released in 2020,[16] looks at the lives of Hatton and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre art director Robert A. Burns, a self-described expert on Hatton.[17]

The Dark Horse comic The Creep focuses on Oxel Karnhus, a private detective with acromegaly, who was modelled after Hatton and his "Creeper" character.

The full story of Hatton's life is told in the Scott Gallinghouse book Rondo Hatton: Beauty Within the Brute (BearManor Media, 2019), which also includes exhaustive production histories of his Universal horror films.

Rondo Hatton Awards; cultural references

[edit]Since 2002, the Rondo Hatton Classic Horror Awards have paid tribute to Hatton in name and likeness.[18] The physical award is a representation of Hatton's face, based on the bust of "The Creeper", whom Hatton portrayed in the 1946 Universal Pictures film House of Horrors.

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1927 | Uncle Tom's Cabin | Slave | Film debut, Uncredited |

| 1929 | Jungle Drums | Shadow | Uncredited |

| 1930 | Hell Harbor | Dance Hall Bouncer | Uncredited |

| 1931 | Safe in Hell | Jury Member | Uncredited |

| 1936 | Wolves of the Sea | Bar Proprietor | Uncredited (stock footage from Hell Harbor) |

| 1938 | In Old Chicago | Rondo - Body Guard | |

| Alexander's Ragtime Band | Barfly | Uncredited | |

| 1939 | Captain Fury | Convict Sitting on Floor | Uncredited |

| The Big Guy | Convict | Uncredited | |

| The Hunchback of Notre Dame | Ugly Man | Uncredited | |

| 1940 | Moon Over Burma | Sailor | Uncredited |

| Chad Hanna | Canvasman | Uncredited | |

| 1942 | It Happened in Flatbush | Baseball Game Spectator | Uncredited |

| The Cyclone Kid | Townsman | Uncredited | |

| Tales of Manhattan | Party Guest | (Fields sequence), Uncredited | |

| The Moon and Sixpence | The Leper | Uncredited | |

| Sin Town | Townsman | Uncredited | |

| The Black Swan | Sailor | Uncredited | |

| 1943 | The Ox-Bow Incident | Gabe Hart | Uncredited |

| Sleepy Lagoon | Hunchback | Uncredited | |

| 1944 | Johnny Doesn't Live Here Anymore | Graves | Uncredited |

| The Pearl of Death | The Hoxton Creeper | ||

| The Princess and the Pirate | Gorilla | Uncredited | |

| 1945 | The Jungle Captive | Moloch the Brute | |

| The Royal Mounted Rides Again | Bull Andrews | ||

| 1946 | The Spider Woman Strikes Back | Mario the Monster Man | |

| House of Horrors | The Creeper | ||

| The Brute Man | Hal Moffat/The Creeper | Final film |

References

[edit]- ^ Duryea, Bill (June 27, 1999). "Floridian: In love with a monster". St Petersburg Times.

- ^ a b Raw, Laurence (2012). Character Actors in Horror and Science Fiction Films, 1930-1960. McFarland. pp. 100–102. ISBN 9780786490493. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ Gallinghouse, Scott; Weaver, Tom. Scripts from the Crypt: The Brute Man. BearManor Media.

- ^ a b c d Fleming, E. J. (2015). Hollywood Death and Scandal Sites: Seventeen Driving Tours with Directions and the Full Story (2nd ed.). McFarland. p. 102. ISBN 9780786496440. Retrieved November 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Guzzo, Paul (October 24, 2017). "Hillsborough High honors courage of horror-star alumnus The Creeper". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved April 4, 2018 – via tampabay.com.

- ^ Sullivan, Ed (January 18, 1938). "Hollywood: All Around the Town". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- ^ a b Meehan, Paul (2010). Horror Noir: Where Cinema's Dark Sisters Meet. McFarland. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-786-46219-3.

- ^ Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Klibanski A, Bronstein MD, Chanson P, Lamberts SW, et al. (September 2013). "A consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of acromegaly complications". Pituitary. 16 (3): 294–302. doi:10.1007/s11102-012-0420-x. PMC 3730092. PMID 22903574.

- ^ Weaver, Tom; Brunas, John (2011). Universal Horrors: The Studio's Classic Films, 1931–1946 (2 ed.). McFarland. p. 557. ISBN 978-0-786-49150-6.

- ^ Levesque, William R.; Shopes, Rich. "On eve of Memorial Day, candles at Tampa cemetery mark sacrifice of veterans". Tampa Bay Times. tampabay.com. Retrieved April 5, 2018.

- ^ Thargs Nerve Centre, prog 61[citation needed]

- ^ Bishop, David (February 24, 2007). "28 Days of 2000 AD #24: Brian Bolland Pt. 1". Vicious Imagery.

- ^ "Extended Matt Smith and Mark Gatiss Interview - Doctor Who Confidential - Series 6 - BBC Three". BBC. October 7, 2011. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Info". RondoandBob.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ "Screening and Press". rondoandbob.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2017.

- ^ "Rondo and Bob". IMDb.

- ^ "Documentary on man who put the gore in 'Texas Chainsaw Massacre'". Austin American-Statesman. Texas. June 4, 2017. Archived from the original on June 3, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ Rondo Hatton Classic Horror Awards, dreadcentral.com; accessed August 30, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- "Rondo Hatton". The Tampa Bay Times. September 29, 1923.

- Hatton, Rondo. "Newshounds, Once Doughboys, Describe First Armistice Day: Southeast of Sedan". The Tampa Bay Times. November 12, 1928.