Roza Shanina

Roza Shanina | |

|---|---|

Shanina in 1944 | |

| Born | 3 April 1924 Edma, Velsky Uyezd, Vologda Governorate, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Died | 28 January 1945 (aged 20) Reichau, East Prussia, Germany |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | USSR |

| Service | Red Army |

| Years of service | 1942–1945 † |

| Rank | Senior sergeant |

| Unit | 184th Rifle Division (3rd Belorussian Front) |

| Commands | 1st Sniper Platoon (184th Rifle Division) |

| Battles / wars |

|

| Awards |

|

Roza Georgiyevna Shanina[a] (Template:Lang-ru, IPA: [ˈrozə ɡʲɪˈorɡʲɪɪvnəˈʂanʲɪnə]; 3 April 1924 – 28 January 1945[b]) was a Soviet sniper during World War II who was credited with over 50 kills. Shanina volunteered for the military after the death of her brother in 1941 and chose to be a sniper on the front line. Praised for her shooting accuracy, Shanina was capable of precisely hitting enemy personnel and making doublets (two target hits by two rounds fired in quick succession).

In 1944, a Canadian newspaper described Shanina as "the unseen terror of East Prussia".[3] She became the first servicewoman of the 3rd Belorussian Front to receive the Order of Glory. Shanina was killed in action during the East Prussian Offensive while shielding the severely wounded commander of an artillery unit. Shanina's actions received praise during her lifetime, but conflicted with the Soviet policy of sparing snipers from heavy battles. Her combat diary was first published in 1965.

Early life

Roza Shanina was born on 3 April 1924 in the Russian village of Edma in Arkhangelsk Oblast to Anna Alexeyevna Shanina, a kolkhoz milkmaid, and Georgiy (Yegor) Mikhailovich Shanin, a logger who had been disabled by a wound received during World War I.[4] Roza was reportedly named after the Marxist revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg[5] and had six siblings: one sister Yuliya and five brothers: Mikhail, Fyodor, Sergei, Pavel, and Marat. The Shanins also raised three orphans.[6] Roza was above average height, with light brown hair and blue eyes, and spoke in a Northern Russian dialect.[7] After finishing four classes of elementary school in Yedma, Shanina continued her education in the village of Bereznik. As there was no school transport at the time, when she was in grades five through seven Roza had to walk 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) to Bereznik to attend middle school.[4] On Saturdays, Shanina again went to Bereznik to take care of her ill aunt Agnia Borisova.[6]

At the age of fourteen, Shanina, against her parents' wishes, walked 200 kilometres (120 mi) across the taiga to the rail station and travelled to Arkhangelsk to study at the college there.[7] (The trek was later attested by Shanina's school teacher Alexander Makaryin.)[8] Shanina left home with little money and almost no possessions;[9] and before moving to the college dormitory she lived with her elder brother Fyodor.[9] Later in her combat diary, Shanina would recall Arkhangelsk's stadium Dinamo, and the cinemas, Ars and Pobeda.[7] Shanina's friend Anna Samsonova remembered that Roza sometimes returned from her friends in Ustyansky District to her college dormitory between 2:00 and 3:00 am. As the doors were locked by that time, the other students tied several bedsheets together to help Roza climb into her room.[10] In 1938, Shanina became a member of the Soviet youth movement Komsomol.[11]

Two years later, Soviet secondary education institutes introduced tuition fees, and the scholarship fund was cut.[12] Shanina received little financial support from home and on 11 September 1941, she took a job in kindergarten No. 2 (lately known as Beryozka) in Arkhangelsk, with which she was offered a free apartment.[12] She studied in the evenings and worked in the kindergarten during the daytime. The children liked Shanina and their parents appreciated her.[9] Shanina graduated from college in the 1941–42 academic year,[13] when the Soviet Union was in the grip of World War II.

Tour of duty

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Arkhangelsk was bombed by the Luftwaffe, and Shanina and other townspeople were involved in firefighting and mounted voluntary vigils on rooftops to protect the kindergarten.[citation needed] Shanina's two elder brothers had volunteered for the military. In December 1941, a death notification was received for her 19-year-old brother Mikhail, who had died during the siege of Leningrad. In response, Shanina went to the military commissariat to ask for permission to serve.[4] Two more of Shanina's brothers died in the war.[12] At that time the Soviet Union had begun deploying female snipers because they had flexible limbs, and it was believed that they were patient, careful and cunning.[15] In February 1942, Soviet women between the ages of 16 and 45 became eligible for the military draft,[16] but Shanina was not drafted that month, as the local military commissariat wanted to spare her from the draft.[17] She first learned to shoot at a shooting range.[17] On 22 June 1942, while still living in the dormitory, Shanina was accepted into the Vsevobuch program for universal military training. After Shanina's several applications, the military commissariat finally allowed her to enroll in the Central Women’s Sniper Training School,[7] where she met Aleksandra "Sasha" Yekimova and Kaleriya "Kalya" Petrova, who became her closest friends, with Shanina calling them "the vagrant three".[7] Honed to a fine point, Shanina scored highly in training and graduated from the academy with honours.[18] She was asked to stay as an instructor there, but refused due to a call of duty.[19] In 1941–1945 a total of 2,484 Soviet female snipers were deployed for the war and their combined tally of kills is estimated to be at least 11,280.[20]

After the momentous victory in the Battle of Stalingrad, the Soviets mounted nationwide counter-offensives and Shanina on 2 April 1944 joined the 184th Rifle Division, where a separate female sniper platoon had been formed. Shanina was appointed a commander of that platoon.[12] Three days later, southeast of Vitebsk, Shanina killed her first German soldier. In Shanina's own words, recorded by an anonymous author, her legs gave way after that first encounter and she slid down into the trench, saying, "I've killed a man."[21] Concerned, the other women ran up saying, "That was a fascist you finished off!"[21] Seven months later, Shanina wrote in her diary that she was now killing the enemy in cold blood and saw the meaning of her life in her actions.[7] She wrote that if she had to do everything over again, she would still strive to enter the sniper academy and go to the front again.[22]

For her actions in the battle for the village of Kozyi Gory (Smolensk Oblast), Shanina was awarded her first military decoration, the Order of Glory 3rd Class, on 18 April 1944. She became the first servicewoman of the 3rd Belorussian Front to receive that order.[23] According to the report of Major Degtyarev (the commander of the 1138th Rifle Regiment), she received the award for the corresponding commendation list, between 6 and 11 April Shanina killed 13 enemy soldiers while subjected to artillery and machine gun fire.[11] By May 1944, her sniper tally increased to 17 confirmed enemy kills,[7] and Shanina was praised as a precise and brave soldier.[12] The same year, on 9 June, Shanina's portrait was featured on the front page of the Soviet newspaper Unichtozhim Vraga.[7]

When Operation Bagration commenced in the Vitebsk region on 22 June 1944, it was decided that female snipers would be withdrawn. They voluntarily continued to support the advancing infantry anyway,[24] and despite the Soviet policy of sparing snipers, Shanina asked to be sent to the front line.[25] Although her request was refused, she went anyway. Shanina was later sanctioned for going to the front line without permission, but did not face a court martial.[26] She wanted to be attached to a battalion or a reconnaissance company, turning to the commander of the 5th Army, Nikolai Krylov. Shanina also wrote twice to Joseph Stalin with the same request.[27]

From 26 to 28 June 1944, Shanina participated in the elimination of the encircled German troops near Vitebsk[28] during the Vitebsk–Orsha Offensive. As the Soviet army advanced further westward, from 8 to 13 July of the same year, Shanina and her sisters-in-arms took part in the battle for Vilnius,[12] which had been under German occupation since 24 June 1941. The Germans were finally driven out from Vilnius on 13 July 1944. During the Soviet summer offensives of that year Shanina managed to capture three Germans.[7]

From her time at the military academy, Shanina became known for her ability to score doublets (two target hits made in quick succession).[citation needed] During one period she crawled through a muddy communications trench each day at dawn to a specially camouflaged pit which overlooked German-controlled territory.[3] She wrote, "the unconditional requirement—to outwit the enemy and kill him—became an irrevocable law of my hunt".[29] Shanina successfully used counter-sniper tactics against a German cuckoo sniper hidden in a tree, by waiting until dusk when the space between the tree branches would be backlit by sunlight and the sniper's nest became visible.[30] On one occasion, Shanina also made use of selective fire from a submachine gun.[31]

Diary

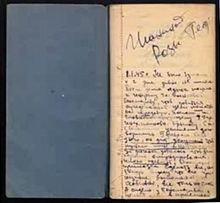

Shanina enjoyed writing and would often send letters to her home village and to her friends in Arkhangelsk.[21] She started writing a combat diary; although diaries were strictly prohibited in the Soviet military,[32] there were some furtive exceptions, such as The Front Diary of Izrael Kukuyev and The Chronicle of War of Muzagit Hayrutdinov.[33][34] To preserve military secrecy, Shanina termed the killed and wounded "blacks" and "reds" respectively in her diary.[25] Shanina kept the diary from 6 October 1944 to 24 January 1945.[35]

After Shanina's death, the diary, consisting of three thick notebooks, was kept by the war correspondent Pyotr Molchanov for twenty years in Kyiv.[36] An abridged version was published in the magazine Yunost in 1965, and the diary was transferred to the Regional Museum of Arkhangelsk Oblast.[36] Several of Shanina's letters and some data from her sniper log have also been published.[37]

East Prussia

In August 1944, advancing Soviet troops had reached the Soviet border with East Prussia and by 31 August of that year Shanina's battle count reached 42 kills.[7] The following month the Šešupė River was crossed. Shanina's 184th Rifle Division became the first Soviet unit to enter East Prussia.[38] At that time, two Canadian newspapers, the Ottawa Citizen and Leader-Post, reported that according to an official dispatch from the Šešupė River front, Shanina killed five Germans in one day as she crouched in a sniper hideout.[3] Later in September, her sniper tally had reached 46 kills,[3][39] of which 15 were made on German soil and seven during an offensive.[40] On 17 September, Unichtozhim Vraga credited Shanina with 51 hits.[24] In the third quarter of 1944, Shanina was given a short furlough and visited Arkhangelsk. She returned to the front on 17 October for one day, and later received an honourable certificate from the Central Committee of Komsomol.[7] On 16 September 1944, Shanina was awarded her second military distinction, the Order of Glory 2nd Class for intrepidity and bravery displayed in various battles against the Germans in that year.[28]

On 26 October 1944 Shanina became eligible for the Order of Glory 1st Class for her actions in a battle near Schlossberg (now Dobrovolsk), but ultimately received the Medal for Courage instead.[41] She was among the first female snipers to receive the Medal for Courage.[25][42] Shanina was awarded the medal on 27 December for the gallant posture displayed during a German counter-offensive on 26 October. There Shanina fought together with Captain Igor Aseyev, a Hero of the Soviet Union, and witnessed his death on 26 October.[43] Shanina, who served as an assistant platoon commander, was ordered to commit the female snipers to combat.[41] Schlossberg was finally retaken from Germans by the troops of the 3rd Belorussian Front on 16 January 1945 during the Insterburg–Königsberg Operation.

On 12 December 1944, an enemy sniper shot Shanina in her right shoulder. She wrote in her diary that she had not felt the pain, "the shoulder was just scalded with something hot."[7] Although the injury, which Shanina described as "two small holes", seemed minor to her, she needed an operation and was incapacitated for several days.[7] She reported in her diary that the previous day she had a prophetic dream in which she was wounded in exactly the same place.[7][38]

On 8 January 1945, Nikolai Krylov formally allowed Shanina to participate in front-line combat, albeit with great reluctance: previously Shanina was denied that permission by the commander of the 184th Rifle Division and the military council of the 5th Army as well.[38] Five days later, the Soviets launched the East Prussian Offensive, which prompted heavy fighting in East Prussia. By 15 January, travelling with divisional logistics, Shanina reached the East Prussian town of Eydtkuhnen (now Chernyshevskoye), where she used white military camouflage.[7] Several days later, she experienced friendly fire from a Katyusha rocket launcher and wrote in her diary, "Now I understand why the Germans are so afraid of Katyushas. What a fire!"[7] At the border of East Prussia, Shanina killed 26 enemy soldiers.[26] The last unit she served in was the 144th Rifle Division. According to the online Book of Memory of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Shanina served in the 205th Special Motorized Rifle Battalion of that division.[44] Shanina had hoped to go to university after the war, or if that was not possible, to raise orphans.[7][38]

In the course of her tour of duty Shanina was mentioned in despatches several times. Her final sniper tally reached fifty-nine confirmed kills[45] (fifty-four, according to other sources[46][47]), including twelve kills during the Battle of Vilnius,[48] with sixty-two enemies knocked out of action.[41] Domestically, her achievements were acknowledged particularly by the war correspondent Ilya Ehrenburg[49] and in the newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda, which said that Shanina was one of the best snipers in her unit and that even veteran soldiers were inferior to her in shooting accuracy.[50] Shanina's exploits were also reported in the Western press, particularly in Canadian newspapers, where she was called "the unseen terror of East Prussia".[3][51] She paid no special attention to the achieved renown, and once wrote that she had been overrated. On 16 January 1945, Shanina wrote in her combat diary: "What I've actually done? No more than I have to as a Soviet person, having stood up to defend the motherland."[12] She also wrote, "The essence of my happiness is fighting for the happiness of others. It's strange, why is it that in grammar, the word "happiness" can only be singular? That is counter to its meaning, after all. ... If it turns necessary to die for the common happiness, then I'm braced to."[22]

Death

In the face of the East Prussian Offensive, the Germans tried to strengthen the localities they controlled against great odds. In a diary entry dated 16 January 1945, Shanina wrote that despite her wish to be in a safer place, some unknown force was drawing her to the front line.[52] In the same entry, she wrote that she had no fear and that she had even agreed to go "to a melee combat." The next day, Shanina wrote in a letter that she might be on the verge of being killed because her battalion had lost 72 out of 78 people.[12] Her last diary entry reports that German fire had become so intense that the Soviet troops, including herself, had sheltered inside self-propelled guns.[7] On 27 January, Shanina was severely wounded and was later found by two soldiers disemboweled, with her chest torn open by a shell fragment.[53] Despite attempts to save her, Shanina died the following day[53] near the Richau estate (later a Soviet settlement of Telmanovka), 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) northwest of the East Prussian village of Ilmsdorf (Novobobruysk). Nurse Yekaterina Radkina remembered Shanina telling her that she regretted having done so little.[53]

By the day of Shanina's death, the Soviets had overtaken several major East Prussian localities, including Tilsit, Insterburg and Pillau, and approached Königsberg. Recalling the moment Shanina's mother received notification of her daughter's death, her brother Marat wrote: "I clearly remembered mother's eyes. They weren't teary anymore. ... 'That's all, that's all'—she repeated".[54] Shanina was buried under a spreading pear tree on the shore of the Alle River—now called the Lava—[12] and was later reinterred in the settlement of Wehlau.[55]

Posthumous honours

In 1964–65 a renewed interest in Shanina arose in the Soviet press, largely due to the publication of her diary. The newspaper Severny Komsomolets asked Shanina's contemporaries to write what they knew about her.[21] Streets in Arkhangelsk, Shangaly and Stroyevskoye were named after her, and the village of Yedma has a museum dedicated to Shanina. The local school where she studied in 1931–35 has a commemorative plate.[56] In Arkhangelsk, regular shooting competitions were organized among members of the paramilitary DOSAAF sport organisation for the Roza Shanina Prize,[26] while Novodvinsk organized an open shooting sports championship in her memory.[57] The village of Malinovka in Ustyansky District started to hold annual cross-country ski races for the Roza Shanina Prize.[58]

In 1985, the Council of Veterans of the Russian Central Women Sniper Academy unsuccessfully requested the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union to posthumously bestow the Order of Glory 1st Class on Shanina[59] (which would have made her a Full Cavalier of that order). In the same year, Russian author Nikolai Zhuravlyov published the book Posle boya vernulas (Returned After Battle). Its title refers to Shanina's words, "I will return after the battle," which she uttered after receiving a note from her battalion commander urging her to return to the rear immediately.[26] Verses have been composed about Shanina, such as those by writer Nikolai Nabitovich.[60] A small memorial stele dedicated to Shanina (part of a three-piece monument) was erected in Bogdanovsky settlement, Ustyansky District.[61]

In 2000, Shanina's name appeared on the war memorial stone of the Siberian State Technological University, although there is no evidence she had any affiliation with it during her life. Russian author Viktor Logvinov controversially wrote in the 1970s that Shanina had studied in the Siberian Forestry Institute and that she was the daughter of an "old Krasnoyarsk communist".[62] The claim was continued by Krasnoyarsk publications in later years, particularly in 2005.[63] In 2013, a wall of memory, featuring graffiti portraits of six Russian war honorees, including Roza Shanina, was opened in Arkhangelsk.[64]

Character and personal life

The war correspondent Pyotr Molchanov, who had frequently met Shanina at the front, described her as a person of unusual will with a genuine, bright nature.[21] Shanina described herself as "boundlessly and recklessly talky" during her college years.[10] She typified her own character as like that of the Romantic poet, painter and writer Mikhail Lermontov, deciding, like him, to act as she saw fit.[7] Shanina dressed modestly and liked to play volleyball.[65] According to Shanina's sister-in-arms Lidiya Vdovina, Roza used to sing her favourite war song "Oy tumany moi, rastumany" ("O My Mists") each time she cleaned her weapon.[21] Shanina had a straightforward character[66] and valued courage and the absence of egotism in people.[7] She once told a story when "about half a hundred frenzied fascists with wild cries" attacked a trench accommodating twelve female snipers, including Shanina: "Some fell from our well-aimed bullets, some we finished with our bayonets, grenades, shovels, and some we took prisoners, having restrained their arms."[21]

Shanina's personal life was thwarted by war. On 10 October 1944, she wrote in her diary, "I can't accept that Misha Panarin doesn't live anymore. What a good guy! [He] has been killed ... He loved me, I know, and so did I ... My heart is heavy, I'm twenty, but I have no close [male] friend".[7] In November 1944, Shanina wrote that she "is flogging into her head that [she] loves" a man named Nikolai, although he "doesn't shine in upbringing and education".[7] In the same entry, she wrote that she did not think about marriage because "it's not the time now".[7] She later wrote that she "had it out" with Nikolai and "wrote him a note in the sense of 'but I'm given to the one and will love no other one'".[7] Ultimately in her last diary record, filled with grim tones, Shanina wrote that she "cannot find a solace" now and is "of no use to anyone".[67]

See also

Notes

- ^ In the commendation lists Shanina's patronymic is Georgiyevna, while in her birth certificate and in several other sources the patronymic goes as Yegorovna. The Russian given name Yegor is a form of Georgiy.[1]

- ^ On Shanina's grave her death day is indicated as 27 January.[2] This article uses the date provided in Shanina's death notification and other sources.

Footnotes

- ^ "Georgiy". Behind the Name. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Роза Шанина: героизм и красота (in Russian). Roshero.ru. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Red Army Girl Unseen Terror of East Prussia". Ottawa Citizen. 20 September 1944. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ a b c Алёшина & Попышева 2010, p. 14

- ^ Зара Хушт. Что в имени тебе моем? [What is in my name for you?]. Краснодарские известия (in Russian). Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ a b Poroshina 1995, p. 52

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Снайпер Роза Шанина [Sniper Roza Shanina] (in Russian). Armoury Online. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 6

- ^ a b c Неизвестное письмо [The Unknown Letter] (PDF). Известия русского Севера (in Russian). September 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ a b Память Победы: она была подругой легендарного снайпера Розы Шаниной [The Memory of Victory: She was a Friend of Legendary Sniper Roza Shanina]. Pravda (in Russian). 11 May 2005. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ a b Наградной лист [Commendation list (of Roza Shanina on her 3rd class Order of Glory)] (in Russian). Podvignaroda.ru. 17 April 1944. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ovsyankin, Yevgeny. "Снайпер Роза Шанина [Sniper Roza Shanina]" (in Russian). Arkhangelsk: Arkhangelsk Pedagogical College. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ^ Ovsyankin, Yevgeny. "В годы Великой Отечественной ..." [In the years of the Great Patriotic War ...] (in Russian). Arkhangelsk Pedagogical College. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ Thomas, Nigel (2013). World War II Soviet Armed Forces (3): 1944–45. Osprey Publishing. p. 1897. ISBN 978-1-78096-428-7.

- ^ Pegler 2006, pp. 175–176

- ^ History of World War II. Marshall Cavendish. 2004. p. 587. ISBN 978-0-7614-7482-1.

- ^ a b Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 15

- ^ Алёшина & Попышева 2010, p. 15

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 16

- ^ Ruchko, Aleksandr. Неженское дело? [A Non-Woman Business?] (in Russian). Gun Magazine. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Melnitskaya, Lidiya (9 February 2006). "Навеки – двадцатилетняя" [Forever Twenty Aged]. Pravda Severa (in Russian). Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ a b Головин, Владимир (2010). "Вместо легких лодочек – кирзачи солдатские." [Kirza Boots Instead of Court Shoes]. Урал (in Russian). Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ Krylov, N.I.; Alekseev N.I.; Dragan I.G. (1970). Навстречу победе (in Russian). Nauka. p. 191.

- ^ a b М. Молчанов (1985). "Девушки – снайперы 5-й армии" [Female Snipers of the 5th Army (from the compilation Born by War)] (in Russian). Молодая гвардия. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ a b c Пётр Молчанов (1976). Жажда боя [Thirst for battle]. Снайперы (compilation) (in Russian). Moscow: OAO "Molodaya gvardiya". Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Russian Snipers of 1941–1945 years; После боя вернусь ... [Returned after battle ...] (excerpts from books by Медведева, В. Е. and Журавлёва, Н. А.)" (in Russian). DOSAAF publishing house. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 45

- ^ a b Наградной лист [Commendation list [of Roza Shanina on her 2nd class Order of Glory]] (in Russian). Podvignaroda.ru. 16 September 1944. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 23

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 24

- ^ Алёшина & Попышева 2010, p. 16

- ^ Ortenberg, David. Сорок третий [The Forty Third] (in Russian). Militera. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Фронтовой дневник Кукуева И. Е [The Front Diary of I. E. Kukuyev]. Strana Kaliningrad (in Russian). 10 July 2007. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Lebedev, Pyotr. В бою до последнего вздоха [In Battle Till the Last Breath]. Республика Татарстан (in Russian). Retrieved 3 January 2011.

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 14

- ^ a b Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 4

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 20

- ^ a b c d Jones, Michael (2011). Total War: From Stalingrad to Berlin. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-84854-246-4.

- ^ "Russ Girl Terror of East Prussia". U.S. News. September 1944. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "Репортаж "Забытый герой – Роза Шанина"" ["The Forgotten Hero – Roza Shanina" report (03:08 time mark)] (in Russian). Pomorfilm.ru. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 13

- ^ Награды девушкам-снайперам [Awards for sniper girls] (PDF). Krasnaya Zvezda (in Russian). 17 January 1945. p. 3. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, pp. 34–35

- ^ "Результаты поиска по сводной базе – все поля" [Database search results] (in Russian). Interregional Informational and Search Center. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ Шанина Роза Георгиевна [Shanina Roza Georgiyevna] (in Russian). Podvignaroda.ru. Retrieved 11 January 2014.

- ^ Brayley, Martin; Ramiro Bujeiro (2001). World War II Allied Women's Services. Osprey Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-84176-053-7.

- ^ Pegler 2006, p. 160

- ^ Yevgeny Ovsyankin (2010). Когда Родина в опасности [When the Motherland is in danger] (in Russian). Nord.pomorsu.ru. Archived from the original on 17 April 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ Д.Д. Панков. Центральная женская школа снайперской подготовки в Подольске [Central Female Sniper Academy in Podolsk] (in Russian). Podolsk.org. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ^ "Sniper Roza Shanina". Krasnaya Zvezda (in Russian). 22 September 1944. p. 2.

- ^ "Woman sniper's total now 46". Leader-Post. 25 September 1944. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 55

- ^ a b c Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 59

- ^ Poroshina 1995, p. 54

- ^ Информация из списков захоронения [Information from the lists of burials] (in Russian). Obd-memorial. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "Вместо учебников – винтовка. Вместо учителей – война" [Rifle instead of textbooks, war instead of teachers] (in Russian). Pomorie.ru. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

- ^ В Новодвинске состоится открытое первенство города по пулевой стрельбе [Novodvinsk will host the city's open shooting sports championship] (in Russian). Arnews. 16 January 2004. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Соревнования по лыжным гонкам на призы Розы Шаниной [Ski race competitions for the Roza Shanina Prize] (in Russian). Belomorsport.ru. 26 February 2013. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 67

- ^ Из поколения победителей [From the generation of victors] (in Russian). Ustyany.net. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ Новый памятник 3 кавалерам ордена "Славы" [A new monument to the three recipients of the Order of Glory] (in Russian). Pomorie.ru. 2 September 2010. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ^ Logvinov, Viktor (1977). В бой идут сибиряки: красноярцы на фронтах и в тылу Великой Отечественной войны. Красноярск : Кн. изд-во. p. 25.

- ^ Красноярцы в Великой Отечественной войне: материалы региональной межвузовской научной конференции, посвященной 60-летию победы СССР в Великой Отечественной войне, 20 апреля 2005 года (in Russian). Краснояр. гос. ун-т, Гос. унив. науч. б-ка Краснояр. края. 2005. p. 65.

- ^ "Стена памяти" украшает Чумбаровку. Pravda Severa (in Russian). 16 September 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ Poloskova, A. (1995). Воспоминания о семье Шаниных. Этот день мы приближали как могли...: устьяки на фронте и в тылу (in Russian). Устьян. район. краевед. музей: 57.

- ^ Kozlova, A. (1995). Никогда не забудем. Этот день мы приближали как могли...: устьяки на фронте и в тылу (in Russian). Устьян. район. краевед. музей: 56.

- ^ Mamonov & Poroshina 2011, p. 58

Sources

- Mogan, A. G. (2020). Stalin's Sniper: The War Diary of Roza Shanina, The Question Mark Publishing, ISBN 979-8611869130

- Pegler, Martin (2006). Out of Nowhere: A History of the Military Sniper. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-140-3.

- Алёшина, А.; Попышева, К. (2010). "Снайпер Роза" [Sniper Roza]. Краеведческий альманах "Отечество" (in Russian). Устьян. район. краевед. музей.

- Mamonov, Vladimir; Poroshina, Natalya (2011). Она завещала нам песни и росы [She bequeathed us songs and dews] (in Russian). Устьянский районный краеведческий музей.

- Poroshina, Natalya (1995). Ее юность рвалась снарядами [Her youth was torn shells]. Этот день мы приближали как могли...: устьяки на фронте и в тылу (in Russian). Устьянский районный краеведческий музей.