Ruhr

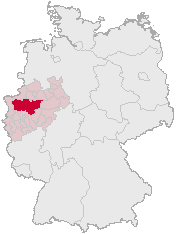

The Ruhr Area, (German Ruhrgebiet, colloquial Ruhr-, Kohlenpott or Revier) is an urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, consisting of a number of large formerly industrial cities bordered by the rivers Ruhr to the south, Rhine to the west, and Lippe to the north. Southwest it borders the Bergisches Land. The area, with some 5.3 million people, is considered part of the larger Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan area of more than 12 million people.

Going from west to east, the area includes the city boroughs of Duisburg, Oberhausen, Bottrop, Mülheim an der Ruhr, Essen, Gelsenkirchen, Bochum, Herne, Hamm, Hagen, and Dortmund as well as parts of the more "rural" districts Wesel, Recklinghausen, Unna and Ennepe-Ruhr. These districts have grown into a large complex forming an industrial landscape of unique size, inhabited by some 5.3 million people, the fifth largest urban area in Europe after Moscow, Greater London, Greater Madrid, and Paris.

History

Towns in the area first grew during the Industrial Revolution, mainly basing their economy on coal mining and steel production. As demand for coal slowly decreased after 1960, the area went through phases of structural crisis and industrial diversification, first developing traditional heavy industry, then moving into service industries and high technology. The proverbial air and water pollution of the area are largely a thing of the past. In 2005 “Essen for the Ruhrgebiet” was the official candidate for nomination as European Capital of Culture for 2010.

In January 1923 French forces occupied the Ruhr area as a means of reprisal after Germany proved incapable of fulfilling reparation payments demanded by the Versailles Treaty. The German government answered with "passive resistance," which meant that coal miners and railway workers refused to obey any instructions by the occupation forces. Production and transportation came to a standstill, but the financial consequences completely ruined public finances in Germany and passive resistance was called off in late 1923.

In World War II, the Allies mounted a campaign specifically to encircle and capture the Ruhr Area. This effort succeeded in surrounding the entire area, trapping several hundred thousand Wehrmacht troops within what was known as the "Ruhr Pocket." Due to its economic significance, the region was very heavily bombed during the War and some of its towns (Dortmund, for example) were among the most devastated cities in Germany.

Following the German unconditional surrender after World War II, the Ruhr area led a perilous existence. The Morgenthau Plan had set the tone in 1944 by requiring the entire area to be stripped of all mining and manufacturing industry, and its industrial worker population to be dispersed as widely as possible. The Ruhr area was then to be governed as an international zone. The French Monnet plan also pushed for an internationalization (see also French proposal from September 1945). The Ruhr Agreement was imposed on the Germans as a condition for permitting them to establish the Federal Republic of Germany.[1] (see also the International Authority for the Ruhr (IAR)).

In the end, the beginning of the Cold War led to increased German control of the area, although permanently limited by the pooling of German coal and steel into a multinational community in 1951 (see European Coal and Steel Community). The nearby Saar area, containing much of Germany's remaining coal deposits, was handed over by the U.S. to economic administration by France as a protectorate in 1947 and did not politically return to Germany until January 1957, with economic reintegration occurring a few years later. Parallel to the question of political control of the Ruhr, the Allies conducted an effort to decrease German industrial potential by limitations on production and dismantling of factories and steel plants, predominantly in the Ruhr. (see also The industrial plans for Germany). By 1950, after the virtual completion of the by then much watered-down "level of industry" plans, equipment had been removed from 706 manufacturing plants in the west and steel production capacity had been reduced by 6,700,000 tons.[2] Dismantling finally ended in 1951.

After Cold War tensions increased, it was anticipated that a Red Army thrust into Western Europe would begin in the Fulda Gap, and would have the Ruhr Area as a primary target.

Language

The local dialect of German is commonly called Ruhrdeutsch or Ruhrpottdeutsch, although there is really no uniform dialect that justifies designation as a single dialect. It is rather a working class sociolect with influences from the various dialects found in the area and changing even with the professions of the workers. A major common influence stems from the coal mining tradition of the area. For example, the Ruhr Area is more commonly known among locals as either "Ruhrpott", where "Pott" is a derivate of "Pütt" (pitmen's term for mine; cp. the English "pit"), or as "Revier" (pitmen's term for seam).

Single words in the dialect are of Polish origin (see below about the Polish immigration in the 19th century), e.g. the word "Mottek" meaning "hammer" which is derived of the Polish word "Młotek" with the same meaning.

The article "das" is often spoken "dat(t)" in Ruhrpottdeutsch, "was" is spoken "wat(t)" etc.

The influx of foreign workers has introduced new expressions arising from the circumstances of industrial work and led to a form of slang typical of certain groups of people in the area. So there is no unified grammar or spelling of the Ruhrdeutsch variations available, yet a substantial amount of literature has been published, including translations of the famous Asterix comic books representing a typical instance of the varieties spoken in the Ruhr Area.

Migration

In the 19th century the Ruhr area pulled up to 500,000 Poles from East Prussia and Silesia due to the event referred to as Ostflucht. By 1925, the Ruhrgebiet had around 3.8 million inhabitants. Most of the new inhabitants migrated from Eastern Europe, however, one could also find a couple of immigrants from France, Ireland, and the United Kingdom. It is believed that these immigrants came from over 140 different nations. After World War II, even more immigrants flocked from the east. These guest workers or "gastarbeiter" came mostly from Italy, and Turkey.

Almost all of their descendants today speak German only and consider themselves Germans, with only their Polish family names remaining as a sign of their past.

In 1900, the main concentrations of the Polish minority were:

- District of Gelsenkirchen, (Westfalia) 13.1 %

- District of Bochum, (Westfalia) 9.1 %

- District of Dortmund, (Westfalia) 7.3 %

- City of Gelsenkirchen, (Westfalia) 5.1 %

Public Transport

All public transport companies in the Ruhr Area are run under the umbrella of the VRR (German: Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr), which provides a uniform ticket system valid for the entire area. The Ruhr Area is well-integrated into the Deutsche Bahn, both in passenger and cargo rail.

External links

- Tourist information on the Ruhrgebiet in English with photos

- Post-Surrender Program for Germany (Sept. 1944)

- Ruhr Delegation of the United States of America, Council of Foreign Ministers American Embassy Moscow, March 24, 1947

- Draft, The President's Economic Mission to Germany and Austria, Report 3, March, 1947; OF 950B: Economic Mission as to Food…; Truman Papers.

- France, Germany and the Struggle for the War-making Natural Resources of the Rhineland Describes the contest for the Ruhr and Saar over the centuries.

- Ruhrgebietsbilder: Photos about the Ruhr

- Photos and stories from students at the 3 Ruhr-area universities

Notes

Bibliography

- Kift, Roy, 'Tour the Ruhr - the English language guide' (second edition 2003) (ISBN: 3-88474-815-7 Klartext Verlag, Essen [1]

- Berndt, Christian. Corporate Germany Between Globalization and Regional Place Dependence: Business Restructuring in the Ruhr Area (2001)

- Crew, David. Town in the Ruhr: A Social History of Rochum, 1860-1914 (1979) (ISBN: 0231043007)

- Gillingham, John. Industry and Politics in the Third Reich: Ruhr Coal, Hitler, and Europe (1985) (ISBN: 0231062605)

- Chauncy D. Harris, "The Ruhr Coal-mining District," Geographical Review, 36 (1946), 194-221.

- Norman J. G. Pounds. The Ruhr: A Study in Historical and Economic Geography (1952) online

- Royal Jae Schmidt. Versailles and the Ruhr: Seedbed of World War II (1968)

- Elaine Glovka Spencer. Management and Labor in Imperial Germany: Ruhr Industrialists as Employers, 1896-1914. Rutgers University Press. (1984) online

See also

- Occupation of the Ruhr (1923-1924)

- Rhine-Ruhr

- Ruhrpolen