STS-400

This article needs to be updated. (March 2009) |

|

STS-400[1] is the Space Shuttle contingency support (Launch On Need) flight, which would be launched using Space Shuttle Endeavour[1] should a major problem occur during STS-125, the final Hubble Space Telescope servicing mission (HST SM-4).

Due to the much lower orbital inclination of the HST compared to the ISS, the shuttle crew will be unable to use the International Space Station as a safe haven and follow the usual plan of recovering the crew with another shuttle at a later date. Instead, NASA has developed a plan to conduct a shuttle-to-shuttle rescue mission, similar to proposed rescue missions for pre-ISS flights.[2][3] This rescue mission would be launched only three days after call up, as the maximum time the crew can remain aboard a damaged orbiter is 23 to 28 days.[4]

It was initially planned that the rescue shuttle would be rolled to Launch Complex 39B two weeks before the planned STS-125 shuttle launch from Launch Complex 39A, creating a rare scenario of two shuttles being on the launch pads at the same time. This occurred in October 2008, however STS-125 was subsequently delayed and rolled back to the VAB. It was planned that after the STS-125 mission, launch pad 39B would continue the conversion for use in Project Constellation for the Ares I rocket.

This mission was originally scheduled to be flown by Endeavour, and numbered as STS-400, but due to an anomaly aboard the Hubble Space Telescope, the STS-125 launch slipped until after STS-119 (the Discovery mission to the ISS), thus the shuttle scheduled to fly this mission was changed to Discovery, and the mission was redesignated STS-401. STS-125 was then delayed further, allowing Discovery mission STS-119 to fly beforehand. This resulted in the rescue mission reverting to Endeavour, and the designation STS-400 being reinstated.[1] In January 2009, it was announced that NASA was evaluating conducting both launches from Complex 39A in order to avoid further delays to Ares I-X, scheduled for launch from LC-39B after STS-400 vacates it.[1] Several of the members on the NASA mission management team said at the time that single pad operations were very doable and likely to be the decision.[5] However, in late March 2009, NASA announced that they would continue with dual-pad operations after all.

Crew

The crew assigned to this mission is a subset of the STS-126 crew[6]

- Christopher Ferguson (3) - Commander

- Eric A. Boe (2) - Pilot

- Robert S. Kimbrough (2) - Mission Specialist 1

- Stephen G. Bowen (2) - Mission Specialist 2

Number in parentheses indicates number of spaceflights by each individual prior and including this mission if flown

Early mission plans

Three different concept mission plans have been evaluated. The first would be to use a shuttle-to-shuttle docking, where the rescue shuttle docks with the damaged shuttle, by flying upside down and backwards, relative to the damaged shuttle.[3] It is unclear whether this would be practical, as the forward structure of either orbiter could collide with the payload bay of the other, resulting in damage to both orbiters. The second option that was evaluated, would be for the rescue orbiter to rendezvous with the damaged orbiter, and perform station-keeping while using its Remote Manipulator System (RMS) to transfer crew from the damaged orbiter. This mission plan would result in heavy fuel consumption. The third concept would be for the damaged orbiter to grapple the rescue orbiter using its RMS, eliminating the need for station-keeping. The rescue orbiter would then transfer crew using its RMS, as in the second option, and would be more fuel efficient than the station-keeping option.[3]

The concept that was eventually decided upon was a modified version of the third concept. The rescue orbiter would use its RMS to grapple the end of the damaged orbiter's RMS.[7]

Preparations

After its most recent mission (STS-123), Endeavour was taken to the Orbiter Processing Facility for routine maintenance. Afterward, Endeavour sat stand-by for STS-326 which would have been flown in the case that STS-124 would not have been able to return to Earth safely. Stacking of the Solid Rocket Boosters began on July 11, 2008. One month later, the External Tank arrived at KSC and was mated with the SRBs on August 29, 2008. Endeavour joined the stack on September 12, 2008 and was rolled out to Pad 39B one week later.

Since STS-126 launched before STS-125, Atlantis rolled back to the VAB on October 20, and Endeavour rolled around to Launch Pad 39B on October 23. When it is time to launch STS-125, Atlantis will rollout to pad 39A and Endeavour will either rollout to pad 39B, or rollout to LC-39A before Atlantis, processed, and then be rolled back to remain stacked in the VAB ready for rollout to LC-39A should launch be required.[1]

Mission plan

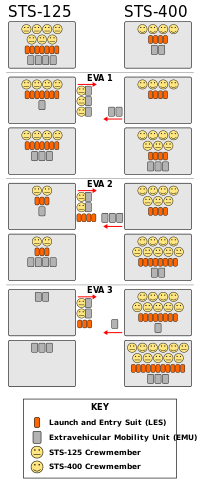

The Mission would begin with extended heatshield inspection using the Orbiter Boom Sensor System on flight day two. On the same day it is planned to rendezvous and grapple with Atlantis as well as to perform the first EVA, during which Megan McArthur, Andrew Feustel and John Grunsfeld would set up a tether between the airlocks. They would also transfer a big size EMU and, after McArthur had repressurized, transfer McArthur's EMU back to Atlantis. Afterwards they would repressurize on Endeavour, ending flight day two activities.

The final two EVA are planned for flight day three. During the first of them Grunsfeld would depressurize on Endeavour in order to help Gregory Johnson and Michael Massimino in transferring an EMU to Atlantis and four ACS suits to Endeavour. He and Johnson would then repressurize on Endeavour, and Massimino would go back to Atlantis. He, along with Scott Altman and Michael Good would then bring the final ACS suits and themselves to Endeavour during the final EVA. They would also be standing by in case the RMS system should malfunction.[7] The rescue orbiter would then land normally, and the damaged orbiter would be disposed of through a destructive re-entry over the Pacific, with the impact area being north of Hawaii.

This mission would likely mark the end of the Space Shuttle program, as it is highly infeasible that the program could continue with just two orbiters.[8]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Bergin, Chris (2009-01-19). "STS-125/400 Single Pad option progress - aim to protect Ares I-X". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 2009-01-19.

- ^ Chris Bergin (2006-05-09). "Hubble Servicing Mission moves up". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ a b c John Copella (2006-07-31). "NASA Evaluates Rescue Options for Hubble Mission". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ http://www.space.com/missionlaunches/090510-sts125-rescue-plan.html

- ^ http://www.nasaspaceflight.com/2009/01/sts-125400-single-pad-option-progress-protect-ares-i-x/ STS-125/400 Single pad options

- ^ NASA (2008-06-16 STS-125: The Final Visit Retrieved on 2008-06-25.

- ^ a b Chris Bergin (2007-11-10). "STS-400 - NASA draws up their Hubble rescue plans". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 2007-10-16.

- ^ Watson, Traci (2005-03-22). "The mission NASA hopes won't happen". USA Today. Retrieved 2006-09-13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)