Salome Alexandra

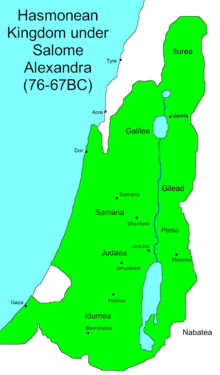

Salome Alexandra or Alexandra of Jerusalem (139–67 BCE), (Template:Lang-he-n, Shelomtzion or ShlomTzion) was the only Jewish regnant queen, with the exception of her own husband's mother whom he had prevented from ruling as his dying father had wished, and of the much earlier usurper Athaliah. The wife of Aristobulus I, and afterward of Alexander Jannaeus,[1] she was the last woman ruler of Judaea, and the last ruler of ancient Judaea to die as the ruler of an independent kingdom.

Her personal genealogy is not given by Josephus. Rabbinical legends designate the Sage Simeon b. Shetah as her brother. [2] If meant and true literally, she was the daughter of Setah Bar Yossei Rabbi and granddaughter of Yossei Bar Yochanan.[3]

On Aristobulus' death (103 BCE), Aristobulus' wife liberated his brother Alexander Jannaeus, who had been held in prison. During the reign of Alexander, who (according to the historian Josephus) apparently married her shortly after his accession,[4] Alexandra seemed to have wielded only slight political influence, as evidenced by the hostile attitude of the king to the Pharisees.

Alexandra received the reins of government (76 or 75 BCE) at Jannaeus' camp before Ragaba, and concealed the king's death until the fortress had fallen, in order that the rigor of the siege might be maintained. She succeeded for a time in quieting the vexatious internal dissensions of the kingdom that existed at the time of Alexander's death; and she did this peacefully and without detriment to the political relations of the Jewish state to the outside world. Alexandra managed to secure assent to a Hasmonean monarchy from the Pharisees, who had suffered intense misery under Alexander and became Judea's ruling class.

Her political ability

The frequent visits to the palace of the chief of the Pharisaic party, Simeon ben Shetach, who was said to be the queen's brother must have occurred in the early years of Alexander's reign, before he had openly broken with the Pharisees. Alexandra does not seem to have been able to prevent the cruel persecution of that sect by her husband; nevertheless the married life of the royal pair seems to have ended cordially: and on his deathbed Alexander entrusted the government, not to his sons, but to his wife.

Her next concern was to open negotiations with the leaders of the Pharisees, whose places of concealment she knew. Having been given assurances as to her future policy, they declared themselves ready to give Alexander's remains the obsequies due to a monarch. By this step she avoided any public affront to the dead king, which, owing to the embitterment of the people, would certainly have found expression at the interment. This might have been attended with dangerous results to the Hasmonean dynasty.

Reestablishment of the Sanhedrin

The Pharisees, who had suffered intense misery under Alexander, now became not only a tolerated section of the community, but actually the ruling class. Alexandra installed as high priest her eldest son, Hyrcanus II a man wholly after the heart of the Pharisees and the Sanhedrin was reorganized according to their wishes. This body had hitherto been, as it were, a "house of lords," the members of which belonged to the aristocracy[citation needed]; but it lost all significance when a powerful monarch was at the helm.[citation needed] From this time it became a "supreme court" for the administration of justice and religious matters, the guidance of which was placed in the hands of the Pharisees.

Her internal and external policy

That the Pharisees, now that the control of affairs was in their hands, did not treat the Sadducees any too gently is very probable; an example is the execution of Diogenes of Judea, by whose advice King Alexander had 800 Pharisees nailed on the cross[citation needed]. The Sadducees were moved to petition the queen for protection against the ruling party. Alexandra, who desired to avoid all party conflict, removed the Sadducees from Jerusalem, assigning certain fortified towns for their residence.

Alexandra increased the size of the army and carefully provisioned the numerous fortified places so that neighbouring monarchs were duly impressed by the number of protected towns and castles which bordered the Israeli frontier. As well, she did not abstain from actual warfare; she sent her son Aristobulus with an army to besiege Damascus, then beleaguered by Ptolemy Menneus. The expedition was reportedly without result. Nevertheless the last days of her reign were tumultuous. Her son Aristobulus endeavored to seize the government and only her death saved her from the embarrassment of being dethroned by her own child.

In legend

Rabbinical legend still further magnifies the prosperity which Judea enjoyed under Alexandra. The Haggadah (Ta'anit, 23a; Sifra, ḤuḲḲat, i. 110) relates that during her rule, as a reward for her piety, rain fell only on Sabbath (Friday) nights; so that the working class suffered no loss of pay through the rain falling during their work-time. The fertility of the soil was so great that the grains of wheat grew as large as kidney-beans; oats as large as olives; and lentils as large as gold denarii. The sages collected specimens of these grains and preserved them to show future generations the reward of obedience to the Law.

[The name "Shalom Zion" is variously modified in rabbinical literature: see Krauss, "Lehnwörter" s.v.; it occurs also in inscriptions; see Lidzbarski, "Handbuch der Nord-Semitischen Epigraphik," s.v., and art. Alphabet in this vol., p. 443.]

Modern use of the name

"Shlomtzion" (שלומציון), derived from the queen's name, is sometimes used as a female first name in contemporary Israel. Among others, the well-known Israeli writer Amos Kenan bestowed that name on his daughter.

In the 1977 Knesset elections Ariel Sharon accepted the advice of Kenan to give the name "Shlomtzion" to a new political party which Sharon was forming at the time (it later merged with the Likud).

References

- ^ That Alexandra, the widow of Aristobulus I, was identical with the one who married his brother Alexander Jannaeus is nowhere explicitly stated by Josephus, who, it is generally inferred, took it for granted that the latter performed the levirate marriage prescribed by the law for the widow of a childless brother deceased.

- ^ Hezser, C. Rabbinic law in its Roman and Near Eastern context http://books.google.com/books?id=SczRfXdmprMC&pg=PA207&lpg=PA207&dq=sister++alexandra++Simeon+b.+Shetah&source=bl&ots=kungMr4YCn&sig=sB1Urv8UcdWg3Jz8XLfHoNYQlGw&hl=en&ei=wWuRSovrItLBlAeLx7CfDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1#v=onepage&q=sister%20%20alexandra%20%20Simeon%20b.%20Shetah&f=false

- ^ T. Stanford Mommaerts, Ancient Genealogy chart - Ansbertus. Available at http://groups.yahoo.com/groups/ancient_genealogy/files/ansbertus.gif, version of 4/11/2005.

- ^ Josephus' statement (Jewish Antiquities xv. 6, § 3), that Hyrcanus II, Jannaeus' eldest son, was eighty years old when he was put to death by Herod, in 31 BCE, is probably erroneous, for that would set the year of his birth as 111 BCE, and Jannaeus himself was born in 125 BCE, so that he could have been but fourteen when Hyrcanus was born to him. It is difficult to understand how a thirteen-year-old boy married a widow of thirty. The statement, made by Josephus (Jewish Antiquities xiii. 11, §§ 1, 2), that during the reign of Aristobulus, Aristobulus' wife, presumably Salome Alexandra, brought about the death of the young prince Antigonus I, because she saw in him a rival of her husband, lacks additional confirmation.

References

- Josephus, Ant. xiii. 11, § 12; 15, § 16;

- idem, B. J. i. 5;

- Heinrich Ewald, History of Israel, v. 392-394;

- Heinrich Grätz, Gesch. d. Juden, 2d ed., iii. 106, 117-129;

- Hitzig, Gesch. d. Volkes Israel, ii. 488-490;

- Emil Schürer, Geschichte i. 220, 229-233;

- Joseph Derenbourg, Essai sur l'Histoire et la Géographie de Palestine, pp. 102-111;

- Wellhausen, I. J. G. pp. 276, 280-285;

- F. W. Madden, Coins of the Jews, pp. 91, 92;

- Hugo Willrich, Judaica: Forschungen zur Hellenisch-Jüdischen Geschichte und Litteratur, 1900, pp. 74, 96.

External links

- Queen Salome Alexandra Entry in Chabad.org Gallery of Our Great

- The Salome No One Knows Biblical Archaeology Review July/August Issue

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)