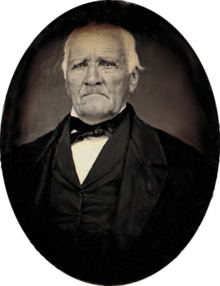

Sam Houston

Sam Houston | |

|---|---|

| |

| 7th Governor of Texas | |

| In office December 21, 1859[1] – March 18, 1861 | |

| Lieutenant | Edward Clark |

| Preceded by | Hardin Richard Runnels |

| Succeeded by | Edward Clark |

| United States Senator from Texas | |

| In office February 21, 1846 – March 4, 1859 | |

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | John Hemphill |

| 3rd President of the Republic of Texas | |

| In office December 13, 1841 – December 9, 1844 | |

| Preceded by | Mirabeau B. Lamar |

| Succeeded by | Anson Jones |

| 1st President of the Republic of Texas | |

| In office October 22, 1836 – December 10, 1838 | |

| Preceded by | David G. Burnet (interim) |

| Succeeded by | Mirabeau B. Lamar |

| 8th Governor of Tennessee | |

| In office October 1, 1827 – April 16, 1829 | |

| Lieutenant | William Hall |

| Preceded by | William Carroll |

| Succeeded by | William Hall |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 2, 1793 Rockbridge County, Virginia |

| Died | July 26, 1863 (aged 70) Huntsville, Texas |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Signature | |

Samuel Houston, known as Sam Houston (March 2, 1793– July 26, 1863), was a 19th-century American statesman, politician, and soldier. He was born in Timber Ridge in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, of Scots-Irish descent. Houston became a key figure in the history of Texas and was elected as the first and third President of the Republic of Texas, U.S. Senator for Texas after it joined the United States, and finally as governor of the state. He refused to swear loyalty to the Confederacy when Texas seceded from the Union, and resigned as governor.[2] To avoid bloodshed, he refused an offer of a Union army to put down the Confederate rebellion. Instead, he retired to Huntsville, Texas, where he died before the end of the Civil War.

His earlier life included migration to Tennessee from Virginia, time spent with the Cherokee Nation (into which he later was adopted as a citizen and took a wife), military service in the War of 1812, and successful participation in Tennessee politics. Houston is the only person in U.S. history to have been the governor of two different states (although other men had served as governors of more than one American territory).

In 1827 Houston was elected Governor of Tennessee as a Jacksonian.[3] In 1829 Houston resigned as Governor and relocated to Arkansas Territory.[4] Shortly afterwards he relocated to Coahuila y Texas, then a Mexican state, and became a leader of the Texas Revolution.[5] He supported annexation by the United States.[6] In 1832 Houston was involved in an altercation with a U.S. Congressman, followed by a high-profile trial.[7] The city of Houston is named after him. Houston's reputation was honored after his death: posthumous commemoration has included a memorial museum, a U.S. Army base, a national forest, a historical park, a university, and the largest free-standing statue of an American.[8]

Early life and family heritage

Sam Houston was the son of Major Samuel Houston and Elizabeth Paxton. Houston's ancestry is often traced to his great-great grandfather Sir John Houston, who built a family estate in Scotland in the late 17th century. His second son John Houston emigrated to Ulster, Ireland, during the English plantation period. Under the system of primogeniture, he did not inherit the estate. After several years in Ireland, John Houston emigrated in 1735 with his family to the North American colonies, where they first settled in Pennsylvania. As it filled with Lutheran German immigrants, Houston decided to move his family with other Scots-Irish who were migrating to lands in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.[9]

An historic plaque in Townland tells the story of the Houston family. It is located in Ballyboley Forest Park near the site of the original John Houston estate. It is dedicated to "One whose roots lay in these hills whose ancestor John Houston emigrated from this area."[citation needed]

The Shenandoah Valley had many farms of Scots-Irish migrants. Newcomers included the Lyle family of the Raloo area, who helped found Timber Ridge Presbyterian Church. The Houston family settled nearby. Gradually John developed his land and purchased slaves.[9] Their son Robert inherited his father's land. His youngest of five sons was Samuel Houston.

Samuel Houston became a member of Morgan's Rifle Brigade and was commissioned a major during the American Revolutionary War. At the time militia officers were expected to pay their own expenses. He had married Elizabeth Paxton and inherited his father's land, but he was not a good manager and got into debt, in part because of his militia service.[9] Their children were born on his family's plantation near Timber Ridge Church, including Sam Houston on March 2, 1793, the fifth of nine children and the fifth son born.

Planning to move on as people did on the frontier to leave debts behind, the elder Samuel Houston patented land in Maryville the county seat of Blount Co.in East Tennessee near relatives. He died in 1807 before he could move with his family, and they moved on without him: Elizabeth taking their five sons and three daughters to the new state.[9] Having received only a basic education on the frontier, young Sam was 14 when his family moved to Maryville.[10] In 1809, at age 16, Houston ran away from home, because he was dissatisfied to work as a shop clerk in his older brothers' store.

He went southwest, where he lived for a few years with the Cherokee tribe led by Ahuludegi (also spelled Oolooteka) on Hiwassee Island, on the Hiwassee River above its confluence with the Tennessee. Having become chief after his brother moved west in 1809, Ahuludegi was known to the European Americans as John Jolly. He became an adoptive father to Houston, giving him the Cherokee name of Colonneh, meaning "the Raven".[11] Houston learned fluent Cherokee, while visiting his family in Maryville every several months. Finally he returned to Maryville in 1812, and at age 19, Houston founded a one-room schoolhouse in Knox county between Maryville and Knoxville.[9] This was the first school built in Tennessee, which had become a state in 1796.

War of 1812

In 1812 Houston reported to a training camp in Knoxville, Tennessee,[10] and enlisted in the 39th Infantry Regiment to fight the British in the War of 1812. By December of that year, he had risen from private to third lieutenant. At the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in March 1814, he was wounded in the groin by a Creek arrow. His wound was bandaged, and he rejoined the fight. When Andrew Jackson called on volunteers to dislodge a group of Red Sticks from their breastwork (fortification), Houston volunteered, but during the assault he was struck by bullets in the shoulder and arm. He returned to Maryville as a disabled veteran, but later took the army's offer of free surgery and convalesced in a New Orleans, Louisiana hospital.[12]

Houston became close to Jackson, who was impressed with him and acted as a mentor. In 1817 Jackson appointed him sub-agent in managing the business relating to Jackson's removal of the Cherokees from East Tennessee to a reservation in what is now Arkansas. He had differences with John C. Calhoun, then Secretary of War, who chided him for appearing dressed as a Cherokee at a meeting. More significantly, an inquiry was begun into charges related to Houston's administration of supplies for the Indians. Offended, he resigned in 1818.[13]

Tennessee politics

Following six months of study at the office of Judge James Trimble, Houston passed the bar examination in Nashville, after which he opened a legal practice in Lebanon, Tennessee.[14] In 1818 Houston was appointed as the local prosecutor in Nashville,[15] and was also given a command in the state militia.

In 1822 Houston was elected to the US House of Representatives for Tennessee, where he was a staunch supporter of fellow Tennessean and Democrat Andrew Jackson. He was widely considered to be Jackson's political protégé, although their ideas about appropriate treatment of Native Americans differed greatly. Houston was a Congressman from 1823 to 1827, re-elected in 1824.

In 1827 he declined to run for re-election to Congress. Instead he ran for, and won, the office of governor of Tennessee, defeating the former governor, William Carroll. He planned to stand for re-election in 1828, but resigned after the dissolution of his first marriage.

Marriage and family

On January 22, 1829, at the age of 35, Houston married 19-year-old Eliza Allen, the daughter of the well-connected planter Colonel John Allen (1776–1833) of Gallatin, Tennessee, who was a friend of Andrew Jackson. Houston's friends thought he was genuinely in love with the girl, but for unknown reasons Eliza left him shortly after the marriage and returned to her father and the couple never reconciled. Neither Houston nor Eliza Allen ever discussed the reasons for their separation; speculation and gossip accredited their split to Eliza being in love with another man.[9] Houston seemed to care greatly for his wife's reputation and took great care to forestall any possible allegations of infidelity on their parts, writing to her father

- April 9, 1829

- Mr. Allen, the most unpleasant & unhappy circumstance has just taken place in the family, & one that was entirely unnecessary at this time. Whatever had been my feelings or opinions in relation to Eliza at one time, I have been satisfied & it is now unfit that anything should be averted to....The only way this matter can now be overcome will be for us all to meet as tho it had never occurred, & this will keep the world, as it should ever be, ignorant that such thoughts ever were. Eliza stands acquitted by me. I have received her as a virtuous wife, & as such I pray God I may ever regard her, & trust I ever shall.

- She was cold to me, and I thought did not love me. She owns that such was one cause of my unhappiness. You can judge how unhappy I was to think I was united to a woman that did not love me. This time is now past, & my future happiness can only exist in the assurance that Eliza and myself can be happy & that Mrs. Allen & you can forget the past, —forgive all & and find your lost peace & you may rest assured that nothing on my part shall be wanting to restore it. Let me know what is to be done.

Houston also requested that one of her relatives

- ...publish in the Nashville papers that if any wretch ever dares to utter a word against the purity of Mrs. Houston I will come back and write the libel in his heart's blood.

In April 1829, in part due to the embarrassment of his well known separation, Houston resigned as governor of Tennessee and went west with the Cherokee to exile in Arkansas Territory. That year he was adopted as a citizen in the nation. There Houston cohabited with Tiana Rogers Gentry, a part-Cherokee widow in her mid-30s. They lived together for several years, and though he was still married under civil law he married Tiana under the Cherokee law.[9] After declining to accompany Houston to Texas in 1832, she later married John McGrady. He officially divorced Eliza Allen in 1837; the following year 1838 Tiana died of pneumonia. (Eliza Allen remarried in 1840, becoming the wife of Dr. Elmore Douglass and stepmother to his 10 children; she bore him 4 children and died in 1861.)[16]

On May 9, 1840, Houston, aged 47 and now the President of Texas, married for a third time. The bride was 21-year-old Margaret Moffette Lea of Marion, Alabama. The union was far longer lived than his two previous unions and produced eight children born between Houston's 50th and 67th years. Margaret Houston acted as a tempering influence on her much older husband and even convinced him to stop drinking. Although the Houstons had numerous houses, they kept only one continuously, Cedar Point (1840–1863) on Trinity Bay.

Their children were the following:

- Sam Houston, Jr., 1843–1894

- Nancy Elizabeth, 1846–1920 (named after her grandmothers)

- Margaret Lea, 1848–1906

- Mary William, 1850–1931

- Antoinette Power, 1852–1932 (named after Margaret's sister)

- Andrew Jackson Houston, 1854-1941 (U.S. Senator from Texas)

- William Rogers, 1858–1891

- Temple Lea Houston, 1860–1905 (named after Margaret's father) (state senator of Texas legislature, 1885–1888)

Indian Territory

Houston went west and lived again among the Cherokee in the Arkansas Territory, who in October 1829 formally adopted him as a citizen of their nation.[13] He set up a trading post (Wigwam Neosho) near Fort Gibson, Cherokee Nation, by the Verdigris River near its confluence with the Arkansas. The Cherokee gave him a nickname meaning "The Raven".[17] During this time Houston was interviewed by the author Alexis de Tocqueville, who was traveling in the United States and its territories. Houston's abandonment of his gubernatorial office and his wife all caused a rift with his mentor President Jackson. They were not reconciled for several years.

Controversy and trial

In 1830 and again in 1832 Houston visited Washington, DC to expose the frauds which government agents committed against the Cherokee.[13] While he was in Washington in April 1832, anti-Jacksonian Congressman William Stanbery of Ohio made accusations about Houston in a speech on the floor of Congress. Attacking Jackson through his protégé, Stanbery accused Houston of being in league with John Van Fossen and Congressman Robert S. Rose. The three men had bid on supplying rations to the various tribes of Native Americans who were being forcibly relocated because of Jackson's Indian Removal Act of 1830.

After Stanbery refused to answer Houston's letters about the accusation, Houston confronted him on Pennsylvania Avenue and beat him with a hickory cane. Stanbery drew one of his pistols and pulled the trigger—the gun misfired.

On April 17 Congress ordered Houston's arrest. During his trial at the District of Columbia City Hall, he pleaded self-defense and hired Francis Scott Key as his lawyer. Houston was found guilty, but thanks to highly placed friends (among them James K. Polk), he was only lightly reprimanded. Stanbery filed charges against Houston in civil court. Judge William Cranch found Houston liable and fined him $500. Houston left the United States for Mexico without paying the fine.

Republic of Texas

The publicity surrounding the trial raised Houston's unfavorable political reputation. He asked his wife, Tiana Rodgers, to go with him to Mexican Texas, but she preferred to stay at their cabin and trading post in Oklahoma. She later married a man named Sam McGrady and died of pneumonia in 1838. Houston married again after her death.

Houston left for Texas in December 1832 and was immediately swept up in the politics of what was still a territory of the Mexican state of Coahuila-Texas. Historians[who?] have speculated that Houston went to Texas at the request of President Jackson to seek U.S. annexation.[citation needed]

Attending the Convention of 1833 as representative for Nacogdoches, Houston emerged as a supporter of William Harris Wharton and his brother, who promoted independence from Mexico, the more radical position of the American settlers and Tejanos in Texas. He also attended the Consultation of 1835. The Texas Army commissioned him as Major General in November 1835. He negotiated a peace settlement with the Cherokee of East Texas in February 1836 to allay their fears about independence. At the convention to declare Texan Independence in March 1836, he was made Commander-in-Chief.

On March 2, 1836, his 43rd birthday, Houston signed the Texas Declaration of Independence. Mexican soldiers killed all those at The Alamo Mission at the end of the Battle of the Alamo on March 6. On March 11, Houston joined what constituted his army at Gonzales: 374 unorganized, unequipped, untrained, and unsupplied recruits. Word of the defeat at the Alamo reached Houston there, and while he waited for confirmation, he organized the recruits as the 1st Regiment Volunteer Army of Texas.

On March 13, short on rations, Houston retreated before the superior forces of Mexican General (and dictator) Antonio López de Santa Anna. Heavy rain fell nearly every day, causing severe morale problems among the exposed troops struggling in mud. After four days' march, near present-day LaGrange, Houston received additional troops and continued east two days later with 600 men. At Goliad, Santa Anna ordered the execution of approximately 400 volunteer Texas militia led by James Fannin, who had surrendered his forces on March 20. Near present-day Columbus on March 26, they were joined by 130 more men, and the next day learned of the Fannin disaster.

Houston continued his retreat eastward towards the Gulf coast, drawing criticism for his perceived lack of willingness to fight. On March 29, camped along the Brazos River, two companies refused to retreat further, and Houston decided to use the opportunity for rudimentary training and discipline of his force. On April 2 he organized the 2nd Regiment, received a battalion of regulars, and on April 11 ordered all troops along the Brazos to join the main army, approximately 1,500 men in all. He began crossing the Brazos on April 12.

Finally, Santa Anna caught up with Houston's army, but had split his own army into three separate forces in an attempt to encircle the Texans. At the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, Houston surprised Santa Anna and the Mexican forces during their afternoon "siesta." The Texans won a decisive victory in under 18 minutes, suffering few casualties, although Houston's ankle was shattered by a stray bullet. Badly beaten, Santa Anna was forced to sign the Treaty of Velasco, granting Texas its independence. Although Houston stayed on briefly for negotiations, he returned to the United States for treatment of his ankle wound.

Houston was twice elected president of the Republic of Texas. On September 5, 1836 he defeated Stephen F. Austin and Henry Smith with a landslide of over 79% of the vote. Houston then served from October 22, 1836, to December 10, 1838, and again from December 12, 1841, to December 9, 1844. On December 20, 1837, Houston presided over the convention of Freemasons that formed the Grand Lodge of the Republic of Texas, now the Grand Lodge of Texas.

While he initially sought annexation by the U.S., Houston dropped that goal during his first term. In his second term, he strove for fiscal prudence and worked to make peace with the Native Americans. He also struggled to avoid war with Mexico, whose forces invaded twice during 1842. In response to the Regulator-Moderator War of 1844, he sent in Republic militia to put down the warfare.

Settlement of Houston

The settlement of Houston was founded in August 1836 by brothers J.K. Allen and A.C. Allen. It was named in Houston's honor and served as capital. Gail Borden helped lay out Houston's streets.

In 1835, one year before being elected first President of the Republic of Texas, Sam Houston founded the Holland Masonic Lodge. The initial founding of the lodge took place in Brazoria and was relocated to what is now Houston in 1837.[18]

The city of Houston served as the capital until President Mirabeau Lamar signed a measure that moved the capital to Austin on January 14, 1839. Between his presidential terms (the constitution did not allow a president to serve consecutive terms), Houston was a representative in the Texas House of Representatives for San Augustine. He was a major critic of President Mirabeau Lamar, who advocated continuing independence of Texas and the extension of its boundaries to the Pacific Ocean.

U.S. Senator from Texas

After the annexation of Texas by the United States in 1845, Houston was elected to the U.S. Senate, along with Thomas Jefferson Rusk. Houston served from February 21, 1846, until March 4, 1859. He was a Senator during the Mexican-American War, when the U.S. defeated Mexico and acquired vast expanses of new territory in the Southwest as part of the concluding treaty.

Throughout his term in the Senate, Houston spoke out against the growing sectionalism of the country. He blamed the extremists of both the North and South, saying: "Whatever is calculated to weaken or impair the strength of [the] Union,– whether originating at the North or the South,– whether arising from the incendiary violence of abolitionists, or from the coalition of nullifiers, will never meet with my unqualified approval."[citation needed]

Houston supported the Oregon Bill in 1848, which was opposed by many Southerners. In his passionate speech in support of the Compromise of 1850, echoing Matthew 12:25, Houston said "A nation divided against itself cannot stand."[19] Eight years later, Abraham Lincoln would express the same sentiment.

Houston opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, and correctly predicted that it would cause a sectional rift in the country that would eventually lead to war, saying: " ... what fields of blood, what scenes of horror, what mighty cities in smoke and ruins– it is brother murdering brother ... I see my beloved South go down in the unequal contest, in a sea of blood and smoking ruin."[citation needed] He was one of only two Southern senators (the other was John Bell of Tennessee) to vote against the act. At the time, he was considered a potential candidate for President of the United States. But, despite the fact that he was a slave-owner, his strong Unionism and opposition to the extension of slavery alienated the Texas legislature and other southern States.

Governor of Texas

Houston ran twice for governor of Texas as a Unionist, unsuccessfully in 1857, and successfully against Hardin R. Runnels in 1859. Upon election, he became the only person in U.S. history to serve as governor of two states, as well as the only governor to have been a foreign head of state. Although Houston was a slave owner and opposed abolition, he opposed the secession of Texas from the Union.

An elected convention voted to secede from the United States on February 1, 1861, and Texas joined the Confederate States of America on March 2, 1861. Houston refused to recognize its legality, but the Texas legislature upheld the legitimacy of secession. The political forces that brought about Texas's secession were powerful enough to replace the state's Unionist governor. Houston chose not to resist, stating, "I love Texas too well to bring civil strife and bloodshed upon her. To avert this calamity, I shall make no endeavor to maintain my authority as Chief Executive of this State, except by the peaceful exercise of my functions ... " He was evicted from his office on March 16, 1861, for refusing to take an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy, writing,

"Fellow-Citizens, in the name of your rights and liberties, which I believe have been trampled upon, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the nationality of Texas, which has been betrayed by the Convention, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of the Constitution of Texas, I refuse to take this oath. In the name of my own conscience and manhood, which this Convention would degrade by dragging me before it, to pander to the malice of my enemies, I refuse to take this oath. I deny the power of this Convention to speak for Texas....I protest....against all the acts and doings of this convention and I declare them null and void.[20]"

He was replaced by Lieutenant Governor Edward Clark. To avoid more bloodshed in Texas, Houston turned down U.S. Col. Frederick W. Lander's offer from President Lincoln of 50,000 troops to prevent Texas's secession. He said, "Allow me to most respectfully decline any such assistance of the United States Government."

After leaving the Governor's mansion, Houston traveled to Galveston. Along the way, many people demanded an explanation for his refusal to support the Confederacy. On April 19, 1861 from a hotel window he told a crowd:

"Let me tell you what is coming. After the sacrifice of countless millions of treasure and hundreds of thousands of lives, you may win Southern independence if God be not against you, but I doubt it. I tell you that, while I believe with you in the doctrine of states rights, the North is determined to preserve this Union. They are not a fiery, impulsive people as you are, for they live in colder climates. But when they begin to move in a given direction, they move with the steady momentum and perseverance of a mighty avalanche; and what I fear is, they will overwhelm the South." [21]

Electoral history

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | Sam Houston | 5,119 | 79.4 | |

| Independent | Henry Smith | 743 | 11.5 | |

| Independent | Stephen F. Austin | 587 | 9.1 | |

Later life

In 1854, Houston was baptized by Rev. Rufus C. Burleson. At the time Burleson was the pastor of the Independence Baptist Church in Washington County, which Houston and his wife attended. Then the wealthiest community in Texas, Independence had won the bid for Baylor College, where Burleson served as second president.[22] Houston was also close friend of Rev. George Washington Baines, who preceded Burleson at the church. Baines was the maternal great-grandfather of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

In 1862, Houston returned to Huntsville, Texas, and rented the Steamboat House; the hills in Huntsville reminded him of his boyhood home in Tennessee. Houston was active in the Masonic Lodge, transferring his membership to Forrest Lodge #19. His health deteriorated in 1863 due to a persistent cough. In mid-July, Houston developed pneumonia. He died on July 26, 1863 at Steamboat House, with his wife Margaret by his side. His last recorded words were, "Texas! Texas! Margaret..."[citation needed]

The inscription on his tomb reads:

- A Brave Soldier. A Fearless Statesman.

- A Great Orator– A Pure Patriot.

- A Faithful Friend, A Loyal Citizen.

- A Devoted Husband and Father.

- A Consistent Christian– An Honest Man.

Sam Houston was buried in Huntsville, Texas, where he lived in retirement; his wife Margaret Lea was buried after her death in Independence at her family's cemetery.

Monuments and museums

- Huntsville, Texas, is the home of the Sam Houston Memorial Museum, a 67 ft (20 m) statue, Sam Houston State University, and Houston's gravesite. The statue (which is the world's largest statue of an American hero, easily visible by motorists traveling on Interstate 45) is the title and subject of a country music song by Merle Haggard.

- A bronze equestrian sculpture of Houston is located in Hermann Park in Houston, Texas This statue depicts Houston atop his horse with a single hand out stretched pointing directly towards San Jacinto.

- The Sam Houston Wayside near Lexington, Virginia, is a 38,000-pound piece of Texas pink granite commemorating Houston's birthplace.

- The Sam Houston Schoolhouse in Maryville, Tennessee, is Tennessee's oldest schoolhouse. In addition to the schoolhouse there is a museum on the grounds.

- USS Sam Houston, an Ethan Allen class submarine, was named after Houston.

- The Sam Houston National Forest, one of four national forests in Texas, was named after Houston.[23]

- The Sam Houston Regional Library and Research Center, located outside of Liberty, Texas has the largest known collection of photographs and illustrations of Houston.

- Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, is named after Houston.

- Many cities in the U.S. have a street, school, or park named for Houston; however, New York City's Houston Street is not named after Sam Houston. Instead, it is named after William Houstoun, and pronounced HOW-stin.

- The State of Texas has placed a statue of Sam Houston inside Statuary Hall of the United States Capitol.

- The Sam Houston Coliseum (now demolished) in Houston, Texas, was named after Houston. The Beatles performed there in 1965.

- There is a mural depicting Sam Houston on a gas tank near State Hwy 225 in Houston.[24]

- Sam Houston High School,[25] in Lake Charles, Louisiana

- Sam Houston Middle School,[26] in Garland, Texas

- Sam Houston Elementary Schools in Lebanon and Maryville, Tennessee; Eagle Pass, Huntsville, Conroe and Bryan,[27] Texas, and Houston, Texas [28]

- A bust of Sam Houston is located inside the Virginia State Capitol Building in Richmond, Virginia

- The City of Houston, Texas was named after Houston

- The City of Houston, Mississippi was named after Houston

- The City of Houston, Minnesota was named after Houston

- A toll road encirling the city of Houston is named the Sam Houston Tollway

- The song "SayHo" by Scott Miller is about Sam Houston

- The State of Tennessee has a county named for him, Houston Co. the county seat is Erin, TN

- In Texas, Houston County is named in honour of the renowned statesman. Its county seat is Crockett, Texas.

Notes

- ^ Williams, John H. (1994), Sam Houston: Life and Times of Liberator of Texas an Authentic American Hero, New York, NY: Touchstone, p. 316, ISBN 0-671-88071-3

- ^ Magazine article, The Biggest Texan: A Profile of Sam Houston, by Margaret Coit, Boys' Life Magazine, April, 1963

- ^ Sam Houston's Wife: A Biography of Margaret Lea Houston, by William Seale, 1992, page 21

- ^ Representing Texas, by Ben R. Guttery, 2008, page 83

- ^ Texas Cemeteries, by Bill Harvey, 2003, page 158

- ^ Our Nation's Archive: The History of the United States in Documents, by Erik A. Bruun, 1999, page 268

- ^ Sam Houston's Texas, by Sue Flanagan, 1964, page 6

- ^ Oddball Texas: A Guide to Some Really Strange Places, by Jerome Pohlen, 2006, page 216

- ^ a b c d e f g James L. Haley, Sam Houston, Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004 Cite error: The named reference "Haley" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Neely, Jack. Knoxville's Secret History, Scruffy City Publishing, 1995.

- ^ Samuel Houston from the Handbook of Texas Online

- ^ Neely, Jack, Knoxville's Secret History, Scruffy City Publishing, 1995

- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Lebanon, Tennessee: A Tour of Our City" (PDF). Lebanon/Wilson County Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved February 5, 2007. [dead link]

- ^ Office History, Nashville District Attorney General

- ^ WNPT.org

- ^ Joseph McElroy, Jefferson Davis, p.79

- ^ Holland Masonic Lodge - History page

- ^ ["http://www.shsu.edu/~pin_www/samhouston/PresAm.html]

- ^ James l. Haley. Sam Houston. University of Oklahoma Press, 2004, pp. 390-91.

- ^ James l. Haley, Sam Houston, University of Oklahoma Press, 2004, p. 397

- ^ General Sam Houston - Texas State Historical Marker, Independence, Texas

- ^ FS.fed.us

- ^ Flickr.com

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Houston Elementary School, Bryan, Texas

- ^ [3]

References

The following are reference sources (alphabetical by author):

- Andrew Jackson-His Life and Times; Brands, H.W.; Doubleday: ISBN 0-385-50738-0.

- The Texas Revolution; Brinkley, William; Texas A&M Press: ISBN 0-87611-041-3.

- Sword of San Jacinto, Marshall De Bruhl; Random House: ISBN 0-394-57623-3.

- Sam Houston, Haley, James L.; University of Oklahoma Press: ISBN 0-8061-3644-8.

- The Raven: A Biography of Sam Houston; James, Marquis; University of Texas Press: ISBN 0-292-77040-5.

- The Eagle and the Raven; Michener, James A.; State House Press: ISBN 0-938349-57-0.

Further reading

- Campbell, Randolph B.; Handlin, Oscar (1993), Sam Houston and the American Southwest, HarperCollins, ISBN 9780065006889

- De Bruhl, Marshall (1993), Sword of San Jacinto: A Life of Sam Houston, Random House, ISBN 9780394576237

- Haley, James L. (2004), Sam Houston, University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 9780806136448

- James, Marquis (1988), The Raven: A Biography of Sam Houston, University of Texas Press, ISBN 9780292770409

- Williams, John Hoyt (1993), Sam Houston: A Biography of the Father of Texas, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 9780671746414

- Williams, John Hoyt (1994), Sam Houston: The Life and Times of the Liberator of Texas, an Authentic American Hero, Simon and Schuster, ISBN 9780671880712

- John F. Kennedy: Profiles in Courage, 1956

External links

- United States Congress. "Sam Houston (id: H000827)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Life of General Houston, 1793-1863 published 1891, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Sam Houston ; David Crockett. published 1901, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Samuel Houston from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Sam Houston Memorial Museum

- Sam Houston Memorial Museum Antiquities Collection From Texas Tides

- Sam Houston's Obituary - The Tri Weekly Telegraph, Houston, Texas July 29, 1863 - TexasBob.com

- Sam Houston Historic Schoolhouse in Maryville, TN USA

- Tennessee Encyclopedia entry

- Tennessee State Library & Archives, Papers of Governor Sam Houston, 1827-1829

- Sam Houston Rode a Gray Horse

- Houston Family Papers, 1836-1869 and undated, in the Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library at Texas Tech University

- 1793 births

- 1863 deaths

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- American people of the War of 1812

- American prosecutors

- Baptists from the United States

- Democratic Party United States Senators

- Governors of Tennessee

- Governors of Texas

- Know-Nothing United States Senators

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Tennessee

- People from Knoxville, Tennessee

- People from Rockbridge County, Virginia

- People of Texas in the American Civil War

- People of the Creek War

- People of the Texas Revolution

- Political violence in the United States

- Presidents of the Republic of Texas

- Tennessee Democratic-Republicans

- Tennessee Jacksonians

- Tennessee lawyers

- Texas Democrats

- Texas Know Nothings

- United States presidential candidates, 1860

- United States Senators from Texas