San Pedro Sacatepéquez, Guatemala

San Pedro Sacatepéquez | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 14°41′0″N 90°38′0″W / 14.68333°N 90.63333°W | |

| Country | |

| Department | Guatemala Department |

| Area | |

| • Total | 57 sq mi (148 km2) |

| Elevation | 7,200 ft (2,200 m) |

| Population (2004) | |

| • Total | 31,503 |

| Climate | Cwb |

San Pedro Sacatepéquez (Spanish pronunciation: [sam ˈpeðɾo sakateˈpekes]) is a municipality in the Guatemala department of Guatemala. According to the 1998 edition of The Columbia Gazetteer of the World, its elevation is 6,890 ft (2,100 m) and it is a market center. Its economy is based on manufacturing, including tile making and textiles, and agriculture, including the cultivation of corn, black beans,and vegetables.[1]

Doctrine of Order of Preachers

After the conquest, the Spanish crown focused on the Catholic indoctrination of the natives. Human settlements founded by royal missionaries in the New World were called "Indian doctrines" or simply "doctrines". Originally, friars had only temporary missions: teach the Catholic faith to the natives, and then transfer the settlements to secular parishes, just like the ones that existed in Spain at the time; the friars were supposed to teach Spanish and Catholicism to the natives. And when the natives were ready, they could start living in parishes and contribute with mandatory tithing, just like the people in Spain.[2]

But this plan never materialized, mainly because the Spanish crown lost control of the regular orders as soon as their friars set course to America. Shielded by their apostolic privileges granted to convert natives into Catholicism, the missionaries only responded to their order local authorities, and never to that of the Spanish government or the secular bishops. The orders local authorities, in turn, only dealt with their own order and not with the Spanish crown. Once a doctrine had been established, the protected their own economic interests, even against those of the King and thus, the doctrines became Indian towns that remains unaltered for the rest of the Spanish colony.

The doctrines were founded at the friars discretion, given that they were completely at liberty to settle communities provided the main purpose was to eventually transfer it as a secular parish which would be tithing of the bishop. In reality, what happened was that the doctrines grew uncontrollably and were never transferred to any secular parish; they formed around the place where the friars had their monastery and from there, they would go out to preach to settlements that belong to the doctrine and were called "annexes", "visits" or "visit towns". Therefore, the doctrines had three main characteristics:

- they were independent from external controls (both ecclesiastical and civilian )

- were run by a group of friars

- had a relatively larger number of annexes.[2]

The main characteristic of the doctrines was that they were run by a group of friars, because it made sure that the community system would continue without any issue when one of the members died.[3]

In 1638, the Order of Preachers split their large doctrines —which meant large economic benefits for them— in groups centered on each one of their six monasteries, and the San Pedro Sacatepéquez doctrine was moved under the Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala monastery jurisdiction:[4]

| Monastery | Doctrines |

|---|---|

| Guatemala |

|

Geographic location

Image gallery

-

A view of the market area and church in San Pedro Sacatepéquez in the mid-1980s.

-

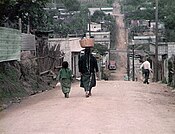

A typical street scene in San Pedro Sacatepéquez, Guatemala Department, in 1983 or 1984.

See also

Notes and references

References

- ^ Cohen,, Saul Bernard (1998). The Columbia gazetteer of the world. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11040-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b van Oss 1986, p. 53.

- ^ van Oss 1986, p. 54.

- ^ a b Belaubre, Christopohe (2001). "Poder y redes sociales en Centroamérica: el caso de la Orden de los Dominicos (1757-1829)" (PDF). Mesoamérica. 41. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b "Municipios del departamento de Guatemala". SEGEPLAN (in Spanish). Guatemala. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Bibliography

- van Oss, Adriaan C. (1986). Catholic Colonialism: A Parish History of Guatemala, 1524-1821. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521527125.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)