Sex work

Sex work is "the exchange of sexual services, performances, or products for material compensation.[1][2][3] It includes activities of direct physical contact between buyers and sellers as well as indirect sexual stimulation".[4] Sex work only refers to voluntary sexual transactions; thus, the term does not refer to human trafficking and other coerced or nonconsensual sexual transactions such as child prostitution. The transaction must take place between consenting adults of the legal age and mental capacity to consent and must take place without any methods of coercion, other than payment.[5][6] The term emphasizes the labor and economic implications of this type of work. Furthermore, some prefer the use of the term because it grants more agency to the sellers of these services.

Types

[edit]In 2004, a Medline search and review of 681 "prostitution" articles was conducted in order to create a global typology of types of sex work using arbitrary categories. Twenty-five types of sex work were identified in order to create a more systematic understanding of sex work as a whole. Prostitution varies by forms and social contexts, including different types of direct and indirect prostitution. This study was conducted in order to work towards improving the health and safety of sex workers.[7]

Types of sex work include various consensual sexual services or erotic performances,[8] involving varying degrees of physical contact with clients:

- Webcam modeling and pornographic modeling. The former is often done via a camming site, and the latter may or may not make use of an adult content-subscription service.[4][9]

- Stripper

- Naked butler

- Pole dancing[10][4]

- Phone sex operators: have sexually oriented conversations with clients, and may do verbal sexual roleplay

- Erotic dancing

- Erotic massage

- Pornographic film acting

- Peepshow performers

- Escort services / Girlfriend experience / Sugar baby

- Sexual surrogates: work with psychoanalysts to engage in sexual activity as part of therapy with their clients.[11]

- Street prostitution

- Indoor prostitution (brothel work, massage parlor-related prostitution, bar or casino prostitution)

- Dominatrix

Legal models

[edit]

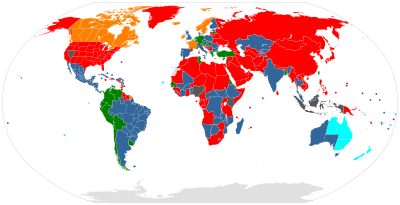

Full criminalization[citation needed] of sex work is the most widely practiced legal strategy for regulating transactional sex.[12] Full criminalization is practiced in China, Russia, and the majority of countries in Africa. In the United States, in which each state has its own criminal code, full contact sex work is illegal everywhere, sex work using a condom is legal only in parts of Nevada; non-contact sex work is a gray and confused area. Under full criminalization the seller, buyer, and any third party involved is subject to criminal penalties. This includes anyone who profits from commercial sex in any location or physical setting. Criminalization has been linked to higher rates of sexually transmitted infections, partner violence, and police harassment.[13] Fear of legal ramifications can deter sex workers from seeking proper sexual health care services and discourage them from reporting crimes of which they were the victim. According to research conducted by Human Rights Watch, criminalization has sex workers more vulnerable to rape, murder, and discrimination due to their marginalized position and ability to be prosecuted by the police even if they come forward as a victim.[14]

Partial criminalization[citation needed] allows for the legalization of both the buying and selling of sex between two consenting parties but prohibits the commercial selling of sex within brothels or public settings such as street solicitation. This has the unintended consequence that it criminalizes the coalition of sex workers, forcing them to work alone and in less safe conditions. Partial criminalization ranges from a variety of legal models such as abolitionism, neo-abolitionism and the Swedish-Nordic Model.[citation needed]

Legalization is currently practiced in parts of South America, Australia, Europe, and in certain counties in the U.S. state of Nevada. The red light district in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, is an example of full legalization, where all aspects of sex work are allowed as long as they are registered with the government. Since the registration process is often expensive and time-consuming, requires legal residence, and may involve regular medical exams, the most marginalized sex workers have to remain illegal, and usually charge less, because they cannot comply with the regulations. This is most common among minority groups, immigrants, and low-income workers.[15]

Decriminalization is the most supported solution by sex workers themselves.[15] The decriminalization of sex work is the only legal solution that offers no criminalization of any party involved in the sex work industry and additionally has no restrictions on who can legally participate in sex work. The decriminalization of sex work would not remove any legal penalties condemning human trafficking. There is no reliable evidence to suggest that decriminalization of sex work would encourage human trafficking.[5] New Zealand was the first country to decriminalize sex work in 2003, with the passage of the Prostitution Reform Act.[16] This is the most advocated for by sex workers because it allows them the most negotiating power with their clients. With full protection under the law, they have the ability to determine their wages, method of protection, and protect themselves from violent offenders. Sex work is one of the oldest professions in existence and even though sex work is criminalized in most places in order to regulate it, the profession has hardly changed at all over time. Those who work in sex trade are more likely to be exploited, trafficked, and victims of assault when sex work is criminalized.[17] Starting in August 2015, Amnesty International, a global movement free of political, religious, or economic interests to protect people from abuse, introduced a policy that requested that all countries decriminalized sex work.[18][19] Amnesty International stated in this policy that decriminalizing sex work would decrease human trafficking through promotion of the health and safety of sex workers by allowing them to be autonomous with protection of the government.[19] This policy gained a large amount of support worldwide from the WHO, UNAIDS, GAATW, and several others, but has not been adopted universally yet.[20][21][22][5][14][23]

History

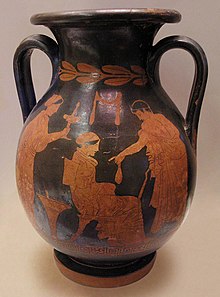

[edit]Sex work, in many different forms, has been practiced since ancient times. It is reported that even in the most primitive societies, there was transactional sex. Prostitution was widespread in ancient Egypt and Greece, where it was practiced at various socioeconomic levels. Hetaera in Greece and geisha in Japan were seen as prestigious members of society for their high level of training in companionship. Attitudes towards prostitution have shifted through history.

During the Middle Ages prostitution was tolerated but not celebrated. It was not until the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century that attitudes turned against prostitution on a large scale and bodies began to be regulated more heavily. These moral reforms were to a large extent directed towards the restriction of women's autonomy. Furthermore, enforcement of regulations regarding prostitution disproportionately impacted the poor.[24]

Sex work has a long history in the United States, yet laws regulating the sale of sex are relatively new. In the 18th century, prostitution was deeply rooted from Louisiana to San Francisco. Despite its prevalence, attitudes towards prostitutes were negative and many times hostile. Although the law did not directly address prostitution at this time, law enforcement often targeted prostitutes. Laws against lewdness and sodomy were used in an attempt to regulate sex work. Red-light districts formed in the 19th century in major cities across the country in an attempt by sex workers to find spaces where they could work, isolated from outside society and corresponding stigma.

Ambiguity in the law allowed for prostitutes to challenge imprisonment in the courts. Through these cases prostitutes forced a popular recognition of their profession and defended their rights and property. Despite sex workers' efforts, social reformers looking to abolish prostitution outright began to gain traction in the early 20th century. New laws focused on the third-party businesses where prostitution took place, such as saloons and brothels, holding the owners culpable for the activities that happened within their premises. Red-light districts began to close. Finally, in 1910 the Mann Act, or "White Slave Traffic Act" made illegal the act of coercing a person into prostitution or other immoral activity, the first federal law addressing prostitution. This act was created to address the trafficking of young, European girls who were thought to have been kidnapped and transported to the United States to work in brothels but criminalized those participating in consensual sex work.[25] Subsequently, at the start of the First World War, a Navy decree forced the closure of sex-related businesses in close proximity to military bases. Restrictions and outright violence led to the loss of the little control workers had over their work. In addition to this, in 1918, the Chamberlain–Kahn Act made it so that any woman found to have a sexually transmitted infection (STI) would be quarantined by the government. The original purpose of this act was to stop the spread of venereal diseases among U.S. soldiers.[26] By 1915 under this act, prostitutes, or those perceived to be prostitutes could be stopped, inspected, and detained or sent to a rehabilitation facility if they were found to test positive for any venereal disease. During World War I, an estimated 3,000 women were detained and examined. The state had made sex workers into legal outcasts.[27] During the Great Depression, black women in New York City accounted for more than 50% of arrests for prostitution.[28]

Types of sex work expanded in the 21st century. Film and later the Internet provided new opportunities for sex work.[29][30] In 1978, Carol Leigh, a sex worker and activist, coined the term "sex work" as it is now used. She looked to combat the anti-pornography movement by coining a term that reflected the labor and economic implications of the work. The term came into popular use in the 1980s. COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics) and other similar groups formed in the 1970s and 80s to push for women's sexual freedom and sex workers' rights. A rift formed within feminism that continues today, with some arguing for the abolishment of sex work and others working for acceptance and rights for sex works.

Stigmas are negative and often derogatory ideas and labels that are placed on one or more members of a community. A prevalent stigma of sex workers that is circulated through various media platforms is the "whore" stigma in which sex workers are labelled as "whores" due to the nature and abundance of client relationships.[31]

A history of media narratives of sex workers was studied to yield the top three most common storylines shown in media about sex works. First, sex workers are shown as carriers and sources of disease. Second, sex work is shown as a social problem that varies in severity. And third, sex work is almost always portrayed in media to occur outdoors, which adds to negative social perceptions that associate sex work to be dirty or public. Across all of these narratives, we typically see a gendered hierarchy in which women of various ages are shown as the sex workers and men are portrayed as the authoritative role of pimps, clients, and law enforcers.[31]

A study in 2006 from the University of Victoria found that when compared to media representations of sex work, firsthand experiences of sex workers were far from similar. It was found that even though inaccurate, media portrayals of sex work are formed from rigid social and cultural scripts that perpetuate stigma and provide influence to news coverage and negative perceptions of sex work.[31]

The HIV/AIDS epidemic presented a new challenge to sex workers. The criminalization of exposing others to HIV/AIDS significantly impacted sex workers. Gay-related immune disorder, or GRID (later changed to AIDS), made headlines in 1985 and led to intermittent sex work. Sex workers were wrongfully held responsible for the transmission of the infection due to the stigma associated with HIV/AIDS, which resulted in discrimination against them. [32] Harm reduction strategies were organized providing testing, counseling, and supplies to stop the spread of the disease. This experience organizing helped facilitate future action for social justice. The threat of violence persists in many types of sex work. Unionization of legal types of sex work such as exotic dancers, lobbying of public health officials and labor officials, and human rights agencies has improved conditions for many sex workers. Nonetheless, the political ramifications of supporting a stigmatized population make organizing around sex work difficult. Despite these difficulties, actions against violence and for increased visibility and rights persist drawing hundreds of thousands of participants.[33] Women in the sex trade are more susceptible to experiencing more stigma and discrimination than men.[34] This stigma and discrimination is attributed to the negative social connotation of the job title "sex worker" and social perspective that sex workers have closer exposure to sexually transmitted infections like HIV and AIDS. These stigmas influence how society interacts with sex workers. In 2011, many sex workers in Hong Kong reported having a verbally or physically abusive interaction with a police officer or healthcare official, which prompted a negative impact on overall health and unequal access to healthcare.[34]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, contact professions (which includes many forms of sex work, amongst others) had been banned (temporarily) in some countries. This has resulted in a reduction in Europe of certain forms of sex work.[35][36][37] In addition, there has been a greater adoption of forms of sex work which do not require physical contact (virtual sexual services).[38][39][40] Examples of sex work that do not require physical contact include webcam modelling and adult content-subscription services (e.g. OnlyFans).[41] Some sex workers have carried on regardless however, also because some virtual sexual services may require an official bank account (or other means of receiving money digitally) and an own private room.[39][38] The COVID-19 pandemic has heightened pre-existing marginalization, inequality, and criminalization of sex workers. With increased global health risks associated with the pandemic, sex workers' in-person services were suspended, posing more financial stressors to an already poverty-stricken population. COVID-19 regulations have specifically posed more threats to the physical and financial safety of socially disadvantaged sex workers who are undocumented, transgender, and of color.[42]

Sex work empowerment

[edit]

International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers

[edit]Dr. Annie Sprinkle and the Sex Workers Outreach Project USA first observed the International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers on December 17, 2003, and has been continuously recognized for the last 17 years.[43] Sprinkle and the Sex Workers Outreach Project USA first observed this day in memory of victims of the Green River Killer in Seattle Washington and has since evolved into an annual, international recognition for other cities who have lost many lives of sex workers, those who experience and have experienced violence, and to empower sex workers.[44] During the week of December 17, the International Day to End Violence Against Sex workers calls attention to hate crimes around the world and social justice organizations work side-by-side with sex worker communities to hold memorials and stage actions to raise awareness of violence by focusing on condemnation of transphobia, xenophobia, racism, criminalization of drug use as well as stigma of sex work in order for sex work to be a safe, non criminalized practice.[45]

Adult content-subscription services

[edit]In adult content-subscription services (e.g. OnlyFans) social media creators can be paid for their content. This content can include selfies, tips, information, tutorials, as well as sex work. OnlyFans creators make a lucrative profit from subscribers who purchase access to their exclusive account every month.[46] OnlyFans has changed sex work in a way that has made it more powerful for the creator, and safer for them to control how they perform their sex work. Many OnlyFans creators that focus on sex work have reported that they receive more subscribers as they post more frequently. It is irrelevant if the posts are "explicit" or not.[47] Several of the women who perform sex work on OnlyFans have regulars that they know everything about from their job description to family member names, to when their surgical procedures are. Although these creators are often paid for and may assist in their subscribers' orgasms, this act is not considered prostitution. Subscribers to OnlyFans sex work accounts have stated that they can get pornography for free anywhere, and that they are paying for a service catered to their personal needs. These subscribers are paying for people to be an online significant other who occasionally helps them achieve an orgasm.[47]

Emotional labor

[edit]Emotional labor is an essential part of many service jobs, including many types of sex work. Through emotional labor sex workers engage in different levels of acting known as surface acting and deep acting. These levels reflect a sex worker's engagement with the emotional labor. Surface acting occurs when the sex worker is aware of the dissonance between their authentic experience of emotion and their managed emotional display. In contrast deep acting occurs when the sex worker can no longer differentiate between what is authentic and what is acting; acting becomes authentic.[48]

Sex workers engage in emotional labor for many different reasons. First, sex workers often engage in emotional labor to construct performances of gender and sexuality.[49][50][51] These performances frequently reflect the desires of a clientele which is mostly composed of heterosexual men. In the majority of cases, clients value women who they perceive as normatively feminine. For women sex workers, achieving this perception necessitates a performance of gender and sexuality that involves deference to clients and affirmation of their masculinity, as well as physical embodiment of traditional femininity.[49][52] The emotional labor involved in sex work may be of a greater significance when race differences are involved. For instance Mistress Velvet, a black, femme dominatrix, advertises herself using her most fetishized attributes. She makes her clients, who are mostly white heterosexual men, read Black feminist theory before their sessions. This allows the clients to see why their participation, as white heterosexual men, contributes to the fetishization of black women.[53]

Both within sex work and in other types of work, emotional labor is gendered in that women are expected to use it to construct performances of normative femininity, whereas men are expected to use it to construct performances of normative masculinity.[48] In both cases, these expectations are often met because this labor is necessary to maximizing monetary gain and potentially to job retention. Indeed, emotional labor is often used as a means to maximize income. It fosters a better experience for the client and protects the worker thus enabling the worker to make the most profit.[49][50][54]

In addition, sex workers often engage in emotional labor as a self-protection strategy, distancing themselves from the sometimes emotionally volatile work.[4][50] Finally, clients often value perceived authenticity in their transactions with sex workers; thus, sex workers may attempt to foster a sense of authentic intimacy.[49][54]

Health care for sex workers

[edit]Mental health care

[edit]Traumatic sexual events and violence put sex workers at a higher risk for mental health disorders. Women in sex work have a higher chance of suffering mental health disorders, and the chance is even greater for those who are women in minority groups including the LGBTQ+ community.[55] A study performed in 2010 concluded that women in sex work were more likely to exhibit signs of PTSD (13%), anxiety (33.7%), and depression (24.4%). Women in sex work experience more obstacles and barriers to gaining mental health care despite their increased risk due to stigma, lack of access to insurance, lack of trust from health care professionals and misogyny.[56][57] A study examining the institutionalized barriers to healthcare faced by female sex workers was conducted in Canada in 2016. The study yielded the finding that about 70% of female sex workers experience one or more institutional barriers to healthcare. These institutional barriers included long wait times, limited hours of operation, and biased treatment or discrimination on behalf of health care providers.[58]

Primary health care

[edit]Sex workers are less likely to seek health care or be eligible to seek health care due to negative stigma. Women in sex work are disproportionally treated worse in health care settings. It is a minimal necessity that women in sex work have access to frequent STI testing and treatment, but it is essential that sex workers have the equal access for regular primary care for other ailments as non-sexworkers.[56] UNAIDS researched the percentage rates of accessible prevention services for sex workers in 2010 around the world and concluded that 51% did not have access.[59] Another obstacle for sex workers to gain health care services is that many are unable to, or unwilling to disclose their profession on required medical paperwork making them ineligible to receive medical care.[19][60]

The population of sex workers has been targeted by the public health industry as a population that has a high risk of HIV infection. This concept is used to strategize marketing materials to sex workers about health resources, but it has been found to actually add to stigma and discrimination of sex workers, further delegitimize prostitution as a source of income, hinder effective health interventions, and perpetuate the idea that being a sex worker is a risk factor for disease.[61] Public health care initiatives that prioritize HIV prevention among sex workers and portray sex workers as a vulnerable population overshadow the rights of sex workers and the legitimacy of sex work as a functional occupation. The title "sex worker" itself was introduced in an attempt to break the association by healthcare industries that links female prostitutes with dirty, immoral, and diseased identities.[61]

Factors in sex workers' health

[edit]There is a possibility that sex work's status as a criminal offense could lead sex workers to engage in practices that impact their own health and safety. In countries where sex work is classified as a crime, condoms can be used as a form of evidence. The Sex Workers Project is an organization that provides legal and social services for sex workers. In a study done regarding the impact of using condoms as evidence, the Brooklyn Defense Services provided data that showed that between 2008 and 2009 there were around 39 sex work-related cases in which condoms were used as evidence.[62] There is a chance that in order to decrease the chance of arrest, sex workers are inclined to participate in unprotected sex. If this is the case, this would contribute to the higher risk of sexually transmitted infections these workers face, as aforementioned.

In Tangent with this, it is not uncommon for sex workers experiencing health difficulties to not take the appropriate steps with healthcare professionals due to fear or distrust in them. A survey done by STAR-STAR, a partner of the human rights organization UNFPA, concluded that almost a quarter of sex workers were denied healthcare services because of their occupation.[63]

Communication between health-care providers and sex workers

[edit]In the interest of providing the best care for Sex Workers seeking health care, transparent communication can enhance the quality of services being provided. This can be practiced on both sides of this relationship. For example, a care provider could include questions in their sexual history questionnaire that pertain to the exchange of sex for money.[64] Being prompted with these kinds of questions could mitigate the anxiety that if the patient is honest about what they do would cause their services to be declined. This might encourage the patient to be more honest about their entire experience and history, which would allow for a better decision to be made in regards to treatment.

Intimate relationships

[edit]A study in Melbourne, Australia, found that sex workers typically experience relationship difficulties as a result of their line of work. This primarily stems from the issue of disclosure of their work in personal relationships. Some sex workers noted that dating ex-clients is helpful as they have had contact with sex workers, and they are aware of their employment.[65]

Although a majority of women in sex work reported that their profession negatively affected them, those that stated a positive effect reported that they had increases sexual self-esteem and confidence.[65] There is very little empirical evidence characterizing clients of sex workers, but they may share an analogous problem. A Scientific American article on sex buyers summarizes a limited field of research which indicates that Johns have a normal psychological profile matching the makeup of the wider male population but view themselves as mentally unwell.[66]

Dolf Zillmann asserts that extensive viewing of pornographic material produces many sociological effects which he characterizes as unfavorable, including a decreased respect for long-term, monogamous relationships, and an attenuated desire for procreation.[67] He claims that pornography can "potentially undermine the traditional values that favor marriage, family, and children" and that it depicts sexuality in a way which is not connected to "emotional attachment, of kindness, of caring, and especially not of continuance of the relationship, as such continuance would translate into responsibilities".[68]

Commodified intimacy

[edit]In clients' encounters with prostitutes or exotic dancers (and potentially other sex workers as well), many seek more than sexual satisfaction. They often seek, via their interactions with sex workers, an affirmation of their masculinity, which they may feel is lacking in other aspects of their lives.[49][52] This affirmation comes in the form of (a simulation of) affection and sexual desire, and "smooth, intimate, affective space, wherein the way that time is managed is governed only by mutual desire and enjoyment."[52] Partly because they are engaged in work during these interactions, prostitutes' experience and interpretation of time tends to be structured instead by desires to maximize income, avoid boredom, and/or avoid detriment to self-esteem.[52]

For sex workers, commodified intimacy provides different benefits. In Brazil, sex workers prioritize foreign men over local men in terms of forming intimate relationships with sex workers. This is a result of local men regarding sex workers as having no worth beyond their occupation. In contrast, foreign men are often accompanied by wealth and status, which are factors that can help a sex worker become independent. Hence sex workers in Brazil are more likely to seek out "ambiguous entanglements" with the foreign men they provide services for, rather than the local men.[69]

Gender differences

[edit]Interviews with men and women escorts illuminate gender differences in these escorts' experiences.[4] On average, women escorts charged much more than men.[70][better source needed] Compared to traditional women escorts, women in niche markets charged lower rates. However, this disparity in rates did not exist for men escorts. Men escorts reported widespread acceptance in the gay community; they were much more likely than women to disclose their occupation.[citation needed] This community acceptance is fairly unusual to the gay community and not the experience of many women sex workers. Also, heterosexual men prostitutes are much more likely than heterosexual women prostitutes to entertain same-gender clients out of necessity, because the vast majority of clients are men.[52] In general, there is a greater social expectation for women to engage in emotional labor than there is for men; there are also greater consequences if they do not.[48]

Risks

[edit]The potential risks sex work poses to the worker vary greatly depending on the specific job they occupy. Compared to outdoor or street-based sex workers, indoor workers are less likely to face violence.[71] Street sex workers may also more likely to use addictive drugs, to have unprotected sex, and to be the victim of sexual assault.[4] HIV affects large numbers of sex workers, of all genders, who engage in prostitution globally. Rape and violence, poverty, stigma, and social exclusion are all common risks faced by sex workers in many different occupations.[24] A study of violence against women engaged in street prostitution found that 68% reported having been raped.[72] Sex workers are also at a high risk of murder. According to Salfati's study, sex workers are 60 to 120 times more likely to be murdered than nonprostitute females.[73] Although these features tend to apply more to sex workers who engage in full service sex work, stigma and safety risks are pervasive for all types of sex work, albeit to different extents.[4][71] Because of the varied legal status of some forms of sex work, sex workers in some countries also face the risk of incarceration, flogging and even the death penalty.[74]

Feminist debate

[edit]Feminist debates on sex work focus primarily on pornography and prostitution. Feminist arguments against these occupations tend to be founded in the notion that these types of work are inherently degrading to women, perpetuate the sexual objectification of women, and/or perpetuate male supremacy.[75] In response, proponents of sex work argue that these claims deny women sex workers' agency, and that choosing to engage in this work can be empowering. They contend that the perspectives of anti-sex work feminists are based on notions of sexuality constructed by the patriarchy to regulate women's expressions sexuality.[76] In fact, many feminists who support the sex industry claim that criminalizing sex work causes more harm to women and their sexual autonomy. An article in the Touro Law Review 2014, focuses on the challenges faced by prostitutes in the U.S and the need for prostitution reform: "[By criminalizing prostitution] women lose the choice to get paid for having consensual sex. A woman may have sex for free, but once she receives something of value for her services, the act becomes illegal".[77] Those who see this as an attack on a women's sexual autonomy also worry about the recent attacks on liberal social policy, such as same sex marriage and abortion on demand, in the U.S. Some liberals also argue that since a disproportionate share of those who choose sex work as a means of income are the poor and disadvantaged, public officials should focus on social policies improving the lives of those choosing to do so rather than condemnation of the "private" means which those victims of society employ.[78] In an interview, Monica Jones, a Black transgender woman and activist, describes the need to address the conflation of sex work and human trafficking. [79]

Debates on sex worker agency

[edit]The topic of sexual labor is often contextualized within opposing abolitionist and sex-positive perspectives.[80][81] The abolitionist perspective typically defines sex work as an oppressive form of labor.[82] According to opponents of prostitution, it is not only the literal purchase of a person's body for sexual exploitation, it also constitutes exertion of power over women both symbolically and materially. This perspective views prostitution and trafficking as directly and intimately connected and therefore calls for the abolition of prostitution in efforts to eliminate the overall sexual exploitation of women and children.[82] Opponents also refute the idea of consent among sex workers by claiming that such consent is merely a submissive acceptance of the traditional exploitation of women. For these reasons, opponents believe that decriminalizing sex work would utterly harm women as a class by maintaining their sexual and economic exploitation while "serving the interests of pimps, procurers and prostitutors".[82] Some Marxist feminists argue sex work is not uniquely exploitative. Heather Berg writes, "Commercial sex exchange is not exploitative because of anything unique to sex; it is exploitative because it is labor under capitalism."[83]

Some sex-positive feminists recognize sex workers as situated within a modern Western sexual hierarchy where a married man and woman are respected while LGBT people, fetishists, and sex workers such as prostitutes and pornographic models are viewed as sexual deviants.[84] According to sex positive feminists, sex law incorporates a prohibition against mixing sex and money in order to sustain this hierarchy. Therefore, the individuals who practice these "deviant" sexual acts are deemed as criminals and have limited institutional support and are subjected to economic sanctions.[84] Sex-positive perspectives challenge this hierarchy by appreciating sexual diversity and rejecting any notion of "normal" sex.[85] With this understanding, people who choose to engage in criminalized sex acts are seen as autonomous sexual beings rather than victims of the sex industry. For black women, agency is viewed as contextual due to historical considerations, and can be regarded as one facet of a complex system of ideals that encompass black women's sexuality over time. One result of this is the way that race relations impact the mobility of black people in the sex industry.[86]

Some liberal feminists believe that a "democratic morality" should judge sexual activity (as if the proclivities of the majority, as well as their proficiency in providing sexual pleasures, should determine the direction of a society's moral compass) "by the way partners treat one another, the presence or absence of coercion, and the quantity and quality of the pleasures they provide".[84] They propound that it should not be an ethical concern whether sex acts are coupled or in groups, same or mixed sex, with or without consensual acts of violence or video, commercial or free.[84]

Relevant television series and films

[edit]See also

[edit]- Decriminalization of sex work

- List of sex worker organizations

- Migrant sex work

- Prostitution

- Revolting Prostitutes

- Sexual assistance

- Transgender sex worker

References

[edit]- ^ Lutnick, Alexandra; Cohan, Deborah (November 2009). "Criminalization, legalization or decriminalization of sex work: What female sex workers say in San Francisco, USA". Reproductive Health Matters. 17 (34): 38–46. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(09)34469-9. PMID 19962636. S2CID 13619772.

- ^ "Prostitution Reform Act 2003 No 28 (as at 26 November 2018), Public Act – New Zealand Legislation". www.legislation.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- ^ Orchard, Treena (2019). "Sex Work and Prostitution". Encyclopedia of Sexuality and Gender. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-59531-3_15-1. ISBN 978-3-319-59531-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Weitzer, Ronald John, ed. (2000). Sex for Sale: Prostitution, Pornography, and the Sex Industry. Routledge. ISBN 9780415922944.

- ^ a b c "Q&A: policy to protect the human rights of sex workers". www.amnesty.org. 31 May 2016. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- ^ Ditmore, Melissa (May 9, 2008). "Sex Work vs. Trafficking: Understanding the Difference". Alternet. Archived from the original on November 27, 2018.

- ^ Harcourt, C; Donovan, B (1 June 2005). "The many faces of sex work". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 81 (3): 201–206. doi:10.1136/sti.2004.012468. PMC 1744977. PMID 15923285.

- ^ Who are sex workers

- ^ Weiss, Benjamin R. (5 April 2017). "Patterns of Interaction in Webcam Sex Work: A Comparative Analysis of Female and Male Broadcasters". Deviant Behavior. 39 (6): 732–746. doi:10.1080/01639625.2017.1304803. hdl:11323/9131. ISSN 0163-9625. S2CID 151727082.

- ^ Green, Alison (2017-11-22). "Top 10 Sex-Related Jobs". www.careeraddict.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ Poelzl, Linda (October 2011). "Reflective Paper: Bisexual Issues in Sex Therapy: A Bisexual Surrogate Partner Relates Her Experiences from the Field". Journal of Bisexuality. 11 (4): 385–388. doi:10.1080/15299716.2011.620454. S2CID 143977403.

- ^ "About the map of Sex Work Law | Sexuality, Poverty and Law". spl.ids.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 2021-05-12. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- ^ Hayes-Smith, Rebecca; Shekarkhar, Zahra (2010-03-01). "Why is prostitution criminalized? An alternative viewpoint on the construction of sex work". Contemporary Justice Review. 13 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1080/10282580903549201. ISSN 1028-2580. S2CID 146238757.

- ^ a b "Why Sex Work Should Be Decriminalized". Human Rights Watch. 2019-08-07. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- ^ a b What do sex workers want? | Juno Mac | TEDxEastEnd, 26 February 2016, retrieved 2019-10-30

- ^ "New Zealand Parliament home page - New Zealand Parliament". www.parliament.nz. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- ^ Albright, E.; d'Adamo, K. (2017-01-01). "Decreasing Human Trafficking through Sex Work Decriminalization". AMA Journal of Ethics. 19 (1): 122–126. doi:10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.1.sect2-1701. ISSN 2376-6980. PMID 28107164.

- ^ "Who We Are". www.amnesty.org. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ a b c "Amnesty International publishes policy and research on protection of sex workers' rights". www.amnesty.org. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ "New WHO guidelines to better prevent HIV in sex workers". World Health Organization. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "HIV and sex work — Human rights fact sheet series 2021" (PDF). UNAIDS. 2 June 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ "Response to UN Women's consultation on sex work". The Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women (GAATW). 2016-10-16. Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ^ "HIV and sex workers". The Lancet. July 23, 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

This Series of seven papers aims to investigate the complex issues faced by sex workers worldwide, and calls for the decriminilisation of sex work, in the global effort to tackle the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

- ^ a b Melissa Hope, Ditmore, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of prostitution and sex work Volumes 1 & 2. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313329685.

- ^ Martin, Michael Rheta; Gelber, Leonard (1978). Dictionary of American History: With the Complete Text of the Constitution of the United States. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 393. ISBN 9780822601241.

- ^ Ann, Moseley (August 2017). Cather Studies, Volume 11 (11 ed.). University of Nebraska Press. p. 384. ISBN 9780803296992.

- ^ Grant, Melissa Gira (18 February 2013). "When Prostitution Wasn't a Crime: The Fascinating History of Sex Work in America". AlterNet. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- ^ Blanshard, Paul (October 1942). "Negro Deliquency in New York". The Journal of Educational Sociology. 16 (2): 115–123. doi:10.2307/2262442. JSTOR 2262442.

- ^ Cunningham, Stewart; Sanders, Teela; Scoular, Jane; Campbell, Rosie; Pitcher, Jane; Hill, Kathleen; Valentine-Chase, Matt; Melissa, Camille; Aydin, Yigit; Hamer, Rebecca (2018). "Behind the screen: Commercial sex, digital spaces and working online". Technology in Society. 53: 47–54. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2017.11.004. hdl:2381/40720.

- ^ Jones, Angela (2015). "Sex Work in a Digital Era". Sociology Compass. 9 (7): 558–570. doi:10.1111/soc4.12282.

- ^ a b c Hallgrimsdottir, Helga Kristin; Phillips, Rachel; Benoit, Cecilia (August 2006). "Fallen Women and Rescued Girls: Social Stigma and Media Narratives of the Sex Industry in Victoria, B.C., from 1980 to 2005". Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie. 43 (3): 265–280. doi:10.1111/j.1755-618X.2006.tb02224.x.

- ^ https://www.aidsactivisthistory.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/aahp-tracey-tief-final.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Sex Work Activists, Allies, and You History". Archived from the original on February 2, 2016.

- ^ a b Mastin, Teresa; Murphy, Alexandra G.; Riplinger, Andrew J.; Ngugi, Elizabeth (2016-03-03). "Having Their Say: Sex Workers Discuss Their Needs and Resources". Health Care for Women International. 37 (3): 343–363. doi:10.1080/07399332.2015.1020538. ISSN 0739-9332. PMID 25719732. S2CID 36035922.

- ^ "Impact of COVID-19 on Sex Workers in Europe". Global Network of Sex Work Projects. 6 July 2020.

- ^ Brooks, Samantha K.; Patel, Sonny S.; Greenberg, Neil (2023). "Struggling, Forgotten, and Under Pressure: A Scoping Review of Experiences of Sex Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 52 (5): 1969–2010. doi:10.1007/s10508-023-02633-3. PMC 10263380. PMID 37311934.

- ^ The Lancet Public Health (2023). "Sex workers health: time to act". The Lancet Public Health. 8 (2): e85. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00006-3. PMID 36709055.

- ^ a b Nelson, Alex J.; Yu, Yeon Jung; McBride, Bronwyn (2020-11-02). "Sex Work during the COVID-19 Pandemic". Exertions. doi:10.21428/1d6be30e.3c1f26b7. S2CID 228835857.

- ^ a b Kabelka, Hannah (2020-05-25). "Back to the Street". KIT Royal Tropical Institute.

- ^ DeLacey, Hannah (2020-05-10). "The precarisation of sex workers during the COVID-19 pandemic". leidenlawblog.nl.

- ^ Dickson, E. J. (2020-05-18). "Sex Workers Built OnlyFans. Now They Say They're Getting Kicked Off". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2021-12-28.

- ^ Bromfield, Nicole F.; Panichelli, Meg; Capous-Desyllas, Moshoula (May 2021). "At the Intersection of COVID-19 and Sex Work in the United States: A Call for Social Work Action". Affilia. 36 (2): 140–148. doi:10.1177/0886109920985131. ISSN 0886-1099. S2CID 232357870.

- ^ NSWP (2010-11-26). "17 December: International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers". Global Network of Sex Work Projects. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ NSWP (2017-05-11). "International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers". Global Network of Sex Work Projects. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ Daring, Christa. "Homepage". December 17th - International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ "Sex workers turned to OnlyFans, but so did a lot of amateurs". Marketplace. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Jacob (2019-02-09). "How OnlyFans Changed Sex Work Forever". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- ^ a b c Hochschild, Arlie Russell (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520054547.

- ^ a b c d e Frank, Katherine (2002). G-Strings and Sympathy: Strip Club Regulars and Male Desire. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822329725.

- ^ a b c Sanders, T. (2005). "'It's Just Acting': Sex Workers' Strategies for Capitalizing of Sexuality". Gender, Work and Organization. 12 (4): 319–342. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.622.3543. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0432.2005.00276.x.

- ^ Trautner, M. (2005). "Doing Gender, Doing Class: the Performance of Sexuality in Exotic Dance Clubs". Gender and Society. 19 (6): 771–788. doi:10.1177/0891243205277253. S2CID 17217211.

- ^ a b c d e Brewis, Joanna; Linstead, Stephen (2003). Sex, Work and Sex Work: Eroticizing Organization. Routledge. ISBN 9781134621774.

- ^ Duberman, Amanda (2018-02-13). "Meet The Dominatrix Who Requires The Men Who Hire Her To Read Black Feminist Theory". Huffington Post. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ a b Sijuwade, P. (1996). "Counterfeit Intimacy: Dramaturgical Analysis of an Erotic Performance". International Journal of Sociology of the Family. 26 (2): 29–41. doi:10.1080/01639625.1988.9967792.

- ^ Puri, Nitasha; Shannon, Kate; Nguyen, Paul; Goldenberg, Shira M. (2017-12-19). "Burden and correlates of mental health diagnoses among sex workers in an urban setting". BMC Women's Health. 17 (1): 133. doi:10.1186/s12905-017-0491-y. ISSN 1472-6874. PMC 5735638. PMID 29258607.

- ^ a b Sawicki, Danielle A.; Meffert, Brienna N.; Read, Kate; Heinz, Adrienne J. (2019). "Culturally Competent Health Care for Sex Workers: An Examination of Myths That Stigmatize Sex-Work and Hinder Access to Care". Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 34 (3): 355–371. doi:10.1080/14681994.2019.1574970. ISSN 1468-1994. PMC 6424363. PMID 30899197.

- ^ Martín-Romo, Laura; Sanmartín, Francisco J.; Velasco, Judith (2023). "Invisible and stigmatized: A systematic review of mental health and risk factors among sex workers". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 148 (3): 255–264. doi:10.1111/acps.13559. hdl:10396/26223. PMID 37105542.

- ^ Socías, M. Eugenia; Shoveller, Jean; Bean, Chili; Nguyen, Paul; Montaner, Julio; Shannon, Kate (2016-05-16). Beck, Eduard J (ed.). "Universal Coverage without Universal Access: Institutional Barriers to Health Care among Women Sex Workers in Vancouver, Canada". PLOS ONE. 11 (5): e0155828. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1155828S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155828. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4868318. PMID 27182736.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information; U.S. National Library of Medicine (December 2012). NSWP GLOBAL SEX WORKER CONSULTATION. World Health Organization.

- ^ Taylor, Anna Kathryn; Mastrocola, Emma; Chew-Graham, Carolyn A. (2016-06-01). "How can general practice respond to the needs of street-based prostitutes?". British Journal of General Practice. 66 (647): 323–324. doi:10.3399/bjgp16X685501. ISSN 0960-1643. PMC 4871300. PMID 27231303.

- ^ a b Uretsky, Elanah (January 2015). "'Sex' – it's not only women's work: a case for refocusing on the functional role that sex plays in work for both women and men". Critical Public Health. 25 (1): 78–88. doi:10.1080/09581596.2014.883067. ISSN 0958-1596. PMC 4309277. PMID 25642103.

- ^ Tomppert, Leigh (April 2012). "Public Health Crisis: The Impact of Using Condoms as Evidence of Prostitution in New York City" (PDF). The PROS Network. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ "Sex workers face high HIV risks – and high barriers to care". United Nations Population Fund. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ "Improving Awareness of and Screening for Health Risks Among Sex Workers". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2023-07-19.

- ^ a b Bellhouse, Clare; Crebbin, Susan; Fairley, Christopher K.; Bilardi, Jade E. (30 October 2015). "The Impact of Sex Work on Women's Personal Romantic Relationships and the Mental Separation of Their Work and Personal Lives: A Mixed-Methods Study". PLOS ONE. 10 (10): e0141575. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1041575B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141575. PMC 4627728. PMID 26516765.

- ^ Westerhoff, Nikolas (1 October 2012). "Why Do Men Buy Sex?". Scientific American. 21 (2s): 60–65. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanbrain0512-60.

- ^ "Report of the Surgeon General's Workshop on Pornography and Public Health: Background Papers: 'Effects of Prolonged Consumption of Pornography' (August 4, 1986)". 1986-08-04. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ^ Zillmann, Dolf; Bryant, Jennings (1988), "Effects of Prolonged Consumption of Pornography on Family Values", Journal of Family Issues, 9 (4): 518–544, doi:10.1177/019251388009004006, S2CID 146337747

- ^ Williams, Erica (8 November 2013). Sex Tourism in Bahia: Ambiguous Entanglements. University of Illinois Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0252079443.

- ^ Fogg, A. (14 October 2014). "Gender differences amongst sex workers online". Archived from the original on 3 October 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ a b Krusi, A (Jun 2012). "Negotiating safety and sexual risk reduction with clients in unsanctioned safer indoor sex work environments: a qualitative study". Am J Public Health. 102 (6): 1154–9. doi:10.2105/ajph.2011.300638. PMC 3484819. PMID 22571708.

- ^ Farley, Melissa; Kelly, Vanessa (2008). "Prostitution". Women & Criminal Justice. 11 (4): 29. doi:10.1300/J012v11n04_04. S2CID 219610839.

- ^ Salfati, C. G.; James, A. R.; Ferguson, L. (2008). "Prostitute Homicides: A Descriptive Study". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 23 (4): 505–43. doi:10.1177/0886260507312946. PMID 18319375. S2CID 21274826.

- ^ Federal Research Division (2004). Saudi Arabia A Country Study. p. 304. ISBN 978-1-4191-4621-3.

- ^ Dworkin, A. "Prostitution and Male Supremacy".

- ^ Davidson, Julia O'Connell (2013). Prostitution, Power and Freedom. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780745668093.

- ^ Carrasquillo, Tesla (October 2014). "Understanding Prostitution and the Need for Reform". Touro Law Review. 30 (3): 697–721.

- ^ "Audacia Ray in Feministe "7 Key American Sex Worker Activist Projects"". Archived from the original on 2017-08-16. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- ^ Gossett, Che; Hayward, Eva (2020-11-01). "Monica Jones". TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly. 7 (4): 611–614. doi:10.1215/23289252-8665271. ISSN 2328-9252.

- ^ Hakim, Catherine (2015). "Economies of Desire: Sexuality and the Sex Industry in the 21st Century" (PDF). Economic Affairs. 35 (3): 329–348. doi:10.1111/ecaf.12134. S2CID 155657726.

- ^ Bernstein, Elizabeth (2007). Temporarily Yours: Intimacy, Authenticity, and the Commerce of Sex. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b c Comte, Jacqueline (2013). "Decriminalization of Sex Work: Feminist Discourses in Light of Research". Sexuality and Culture. 18: 196–217. doi:10.1007/s12119-013-9174-5. S2CID 143978838.

- ^ Berg, Heather (2014). "Working for Love, Loving for Work: Discourses of Labor in Feminist Sex-Work Activism". Feminist Studies. 40 (3): 694. doi:10.1353/fem.2014.0045. JSTOR 10.15767/feministstudies.40.3.693. S2CID 152198638 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d Rubin, Gayle (1984). "Thinking Sex: Notes toward a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality" (PDF). Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality: 275–284.

- ^ Windsor, Elroi (2014). Sex Matters: Future Visions for a Sex-Positive Society. New York: Norton. pp. 691–699. ISBN 978-0-393-93586-8.

- ^ Miller-Young, Mireille (2014). A Taste for Brown Sugar, Black Women in Pornography. Duke University Press Book. ISBN 978-0822358282.

- ^ "Buying Sex (2013)". IMDB. May 2013.

- ^ "Meet the Fokkens (2011)". IMDb. December 2011.