Special reconnaissance

- This article is a subset article under Human Intelligence. For a complete hierarchical list of articles, see the intelligence cycle management hierarchy.

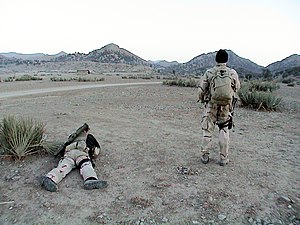

Special reconnaissance (SR) is conducted by small units of highly trained military personnel, usually from special forces units or military intelligence organizations, who operate behind enemy lines, avoiding direct combat and detection by the enemy. As a role, SR is distinct from commando operations, but both are often carried out by the same units. The SR role frequently includes covert direction of air and missile attacks, in areas deep behind enemy lines, placement of remotely monitored sensors and preparations for other special forces. Like other special forces, SR units may also carry out direct action (DA) and unconventional warfare (UW), including guerrilla operations.

SR was recognized as a key special operations capability by a former US Secretary of Defense William J. Perry: "Special Reconnaissance is the conduct of environmental reconnaissance, target acquisition, area assessment, post-strike assessment, emplacement and recovery of sensors, or support of Human Intelligence (HUMINT) and Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) operations."[1]

In international law, SR is not regarded as espionage if combatants are in proper uniforms, regardless of formation, according to the Hague Convention of 1907,[2] or the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.[3] However, some countries do not honor these legal protections, as was the case with the Nazi "Commando Orders" of World War II, which were held to be illegal at the Nuremberg Trials.

In intelligence terms, SR is a human intelligence (HUMINT) collection discipline. Its operational control is likely to be inside a compartmented cell of the HUMINT, or possibly the operations, staff functions. Since such personnel are trained for intelligence collection as well as other missions, they will usually maintain clandestine communications to the HUMINT organization and will be systematically prepared for debriefing. They operate significantly farther than the most forward friendly scouting and surveillance units; they may be tens to hundreds of miles deeper.

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

While SR has been a function of armies since ancient times, specialized units with this task date from the lead-up to World War II.

In 1938, the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) and the War Office both set up special reconnaissance departments. These later formed the basis of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), which conducted operations in occupied Europe.

During the Winter War (1939–40) and the Continuation War (1941–44), Finland employed several kaukopartio (long range patrol) units.

From 1941, volunteers from various countries formed, under the auspices of the British Army, the Long Range Desert Group and Special Air Service, initially for service in the North African Campaign.

In 1942, following the onset of the Pacific War, the Allied Intelligence Bureau, was set up in Australia. Drawing on personnel from Australian, British, New Zealand and other Allied forces, it included Coastwatchers and "special units" that undertook reconnaissance behind enemy lines.

The US Government established the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), modelled on the British SOE, in June 1942. Following the end of the war OSS became the basis for the CIA.

During the Vietnam War, respective division and brigades in-country trained their Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol members (now known as the Long Range Surveillance units). However, the US Army's 5th Special Forces Group held an advanced course in the art of patrolling for potential Army and Marine team leaders at their Recondo School in Nha Trang, Vietnam, for the purpose of locating enemy guerrilla and main force North Vietnamese Army units, as well as artillery spotting, intelligence gathering, forward air control, and bomb damage assessment.[4]

Spectrum of capabilities: LRS and SR

Conventional military forces, at battalion level, will often have scout platoons that can perform limited reconnaissance beyond the main line of troops. For example, reorganized US Army brigade combat teams, the new US Army Unit of Action, are gaining reconnaissance squadrons (i.e., light battalion sized units). US Army Battlefield Surveillance Brigades (BfSB) have specialized Long Range Surveillance (LRS) companies.[5]

Long Range Surveillance 6-man teams (LRS) operate behind enemy lines, deep within enemy territory, forward of battalion reconnaissance teams and cavalry scouts in their assigned area of interest. The duration of an LRS mission depends on equipment and supplies the team must carry, movement distance to the objective area, and resupply availability. LRS teams normally operate up to seven days without resupply depending on terrain and weather.

SR units are well armed, since they may have to defend themselves if they are detected as their exfiltration support needs time to get to them.[6] During the 1991 Gulf War, British SAS and United States Army and Air Force Special Operations Forces units were sent on SR to find mobile Iraqi SCUD launchers, originally to direct air strikes onto them. When air support was delayed, however, the patrols might attack key SCUD system elements with their organic weapons and explosives. See The Great SCUD Hunt.

While there are obvious risks to doing so,[3] SR-trained units can operate out of uniform. They may use motorcycles, four-wheel-drive vehicles, or multiple helicopter lifts in their area of operations, or have mountaineering or underwater capability. Most SR units are trained in advanced helicopter movement and at least basic parachuting; some SR will have HAHO and HALO advanced parachute capability.

SR will have more organic support capabilities, including long-range communications, possibly SIGINT and other means of collecting technical intelligence, and usually at least one medical technician who can do more than basic first aid.

See Special Reconnaissance organizations for national units. All these organizations have special operations roles, with SR often by specialists within them. Certain organizations are tasked for response involving areas contaminated by chemicals, biological agents, or radioactivity.

Since reconnaissance is a basic military skill, "special" reconnaissance refers to the means of operating in the desired area, and the nature of the mission. In US Army doctrine,[1][7] there are five basic factors:

- Physical distances. The area of operations may be well beyond the forward line of troops, and require special skills to reach the area.

- Political considerations. Clandestine insertion also may be a requirement. If there is a requirement to work with local personnel, language skills and political awareness may be critical.

- Lack of required special skills and expertise. The most basic requirement for SR is to be able to remain unobserved, which may take special skills and equipment. If there is a requirement to collect intelligence, skills anywhere from advanced photography to remote sensor operation may be required.

- Threat capabilities. This usually relates to the need to stay clandestine, potentially against an opposing force with sophisticated intelligence capabilities. Such capabilities may be organic to a force, or be available from a sponsoring third country.

- Follow-on special forces missions. This is the concept of preparing for other functions, such as Unconventional Warfare (UW) (i.e., guerrilla) or Foreign Internal Defense (FID) (i.e., counter-guerrilla) operations.

Appropriate missions

Special forces units that perform SR are usually polyvalent, so SR missions may be intelligence gathering in support of another function, such as counter-insurgency, foreign internal defense (FID), guerrilla/unconventional warfare (UW), or direct action (DA).

Other missions may deal with locating targets and planning, guiding, and evaluating attacks against them.

Target analysis could go in either place. If air or missile strikes are delivered after the SR team leaves the AO, the SR aspect is intelligence, but if the strikes are to be delivered and possibly corrected and evaluated while the SR team is present, the SR mission is fires-related.

Intelligence related missions

Every SR mission will collect intelligence, even incidentally. Before a mission, SR teams will usually study all available and relevant information on the area of operations (AO). On their mission, they then confirm, amplify, correct, or refute this information.

Assessment, whether by clandestine SR or overt study teams, is a prerequisite for other special operations missions, such as UW or FID. DA or counter-terror (CT), usually implies clandestine SR.

Hydrographic, meteorological and geographic reconnaissance

Mission planners may not know if a given force can move over a specific route. These variables may be hydrographic, meteorological, and geographic. SR teams can resolve trafficability or fordability, or locate obstacles or barriers.[7]: 1–4

MASINT sensors exist for most of these requirements. The SR team can emplace remotely operated weather instrumentation. Portable devices to determine the depth and bottom characteristics of waters are readily available, as commercial fishing equipment or more sophisticated devices for military naval operations.

Remote-viewing MASINT sensors to determine the trafficability of a beach are experimental. Sometimes, simple observation or use of a penetrometer or weighted cone that measures how deeply weights will sink into the surface are needed. These however have to be done at the actual site. Beach measurements are often assigned to naval SR units like the United States Navy SEALs or UK Special Boat Service.

Beach and shallow water reconnaissance, immediately before an amphibious landing is direct support to the invasion, not SR. SR would determine if a given beach is suitable for any landing, well before the operational decision to invade.

There is a blurred line between SR and direct action in support of amphibious operations, when an outlying island is captured, with the primary goal of using it as a surveillance base and for support functions. While the attack by elements of the 77th Infantry Division on Kerama Retto before the main battle was a large scale operation by SR standards, it is an early example. Operation Trudy Jackson, the capture of an island in the mouth of the harbor before the Battle of Inchon by a joint CIA/military team led by Navy LT Eugene Clark, landed at Yonghung-do is much more in the SR/DA realm. Clark apparently led numerous SR and DA operations during the Korean War, some of which may still be classified.

IMINT

Basic photography[7]: C-9–C-14 and sketching is usually a skill for everyone performing SR missions. More advanced photographic technique may involve additional training or attaching specialists.

Lightweight unmanned aerial vehicles with imagery and other intelligence collection capability are potentially useful for SR, since small UAVs have low observability. SR team members can be trained to use them, or specialists can be attached. The UAV may transmit what it sees, using one or more sensors, either to the SR team or a monitoring headquarters. Potential sensors include stabilized and highly magnified photography, low-light television, thermal imagers and imaging radar. Larger UAVs, which could be under the operational control of the SR team, could use additional sensors including portable acoustic and electro-optical systems.

SIGINT (and EW)

If there is a ground SIGINT requirement deep behind enemy lines, an appropriate technical detachment may be attached to the SR element. For SIGINT operations, the basic augmentation to United States Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance (Force Recon) is a 6-man detachment from a Radio Reconnaissance Platoon. There is a SIGINT platoon within the Intelligence Company of the new Marine Special Operations Support Group.[8]

Army Special Forces have the Special Operations Team-Alpha that can operate with a SF team, or independently. This low-level collection team typically has four men.[9] Their primary equipment is the AN/PRD-13 SOF SIGINT Manpack System (SSMS), with capabilities including direction-finding capability from 2 MHz to 2 GHz, and monitoring from 1 to 1400 MHz. SOT-As also have the abilities to exploit computer networks, and sophisticated communications systems.[10]

The British 18 (UKSF) Signal Regiment provides SIGINT[11] personnel, including from the preexisting 264 (SAS) Signals Squadron and SBS Signals Squadron to provide specialist SIGINT, secure communications, and information technology augmentation to operational units. They may be operating in counterterror roles in Iraq in the joint UK/US TASK FORCE BLACK.[12]

If the unit needs to conduct offensive electronic warfare, clandestinity requires that, at the very least, any ECM devices be operated remotely, either by the SR force or, preferably, by remote electronic warfare personnel after the SR team leaves the area.[13]

MASINT and remote surveillance

Passive MASINT sensors can be used tactically by the SR mission. SR personnel also may emplace unmanned MASINT sensors like seismic, magnetic, and other personnel and vehicle detectors for subsequent remote activation, so their data transmission does not interfere with clandestinity. Remote sensing is generally understood to have begun with US operations against the Laotian part of the Ho Chi Minh trail, in 1961. Under CIA direction, Lao nationals were trained to observe and photograph traffic on the Trail.[14] This produced quite limited results, and, in 1964, Project LEAPING LENA parachuted in teams of Vietnamese Montagnards led by Vietnamese Special Forces.

The very limited results from LEAPING LENA led to two changes. First, US-led SR teams, under Project DELTA sent in US-led teams. Second, these Army teams worked closely with US Air Force Forward Air Controllers (FAC) which were enormously helpful in directing US air attacks by high-speed fighter-bombers, BARREL ROLL in northern Laos and Operation STEEL TIGER. While the FACs immediately helped, air-ground cooperation improved significantly with the use of remote geophysical MASINT sensors, although MASINT had not yet been coined as a term.[15]

The original sensors, a dim ancestor of today's technologies, started with air-delivered sensors under Operation Igloo White, such as air-delivered Acoubuoy and Spikebuoy acoustic sensors.[16] These cued monitoring aircraft, which sent the data to a processing center in Thailand, from which target information was sent to the DELTA teams.

Closer to today's SR-emplaced sensors was the Mini-Seismic Intrusion Detector (MINISID). Unlike other sensors employed along the trail it was specifically designed to be hand delivered and implanted. The MINISID and its smaller version the MICROSID were personnel detection devices often used in combination with the magnetic intrusiondetector (MAGID). Combining sensors in this way improved the ability of individual sensors to detect targets and reduced false alarms. Today's AN/GSQ-187 Improved Remote Battlefield Sensor System (I-REMBASS) is a passive acoustic sensor which with other MASINT sensors detects vehicles and humans on a battlefield,[17] multiple acoustic, seismic, and magnetic sensors combine modes to discriminate real targets. It will be routine for SR units both to emplace such sensors for regional monitoring by higher headquarters' remote sensing centers, but also as an improvement over tripwires and other improvised warnings for the patrol.

Passive acoustic sensors provide additional measurements that can be compared with signatures and used to complement other sensors. For example, a ground search radar may not be able to differentiate between a tank and a truck moving at the same speed. Adding acoustic information may quickly help differentiate them.

TECHINT

Capture of enemy equipment for TECHINT analysis is a basic SR mission. Capture of enemy equipment for examination by TECHINT specialists may be a principal part of SR patrols and larger raids, such as the World War II Operation Biting raid on Saint-Jouin-Bruneval, France, to capture a German Würzburg radar. They also captured a German radar technician.

Not atypically for such operations, a technical specialist (radar engineer Flight Sergeant C.W.H. Cox) was attached to the SR unit. Sometimes technical specialists without SR training have taken their first parachute jump on TECHINT-oriented missions.

Cox told them what to take, and what that could not be moved to photograph. Cox had significant knowledge of British radar, and conflicting reports say that the force was under orders to kill him rather than let him be captured.[18] This was suggested an after-the-action rumor, as Cox was a technician, and the true radar expert that could not be captured, Don Preist, stayed offshore but in communications with the raiders.[18] Preist also had ELINT equipment to gain information on the radar.

Publicising this operation helped British morale but was poor security. Had the force destroyed the site and retreated without any notice, the Germans might have suspected what technology had been compromised. So the Germans fortified their radar sites, and the British, realising similar raids could target them, moved their radar research center, TRE farther inland.[18]

A mixture of SR, DA, and seizing opportunities characterized Operation Rooster 53, originally planned as a mission to locate and disable a radar. It turned into an opportunity to capture the radar and, flying overloaded helicopter, bring the entire radar back to the electronic TECHINT analysts. The Sayeret Matkal reconnaissance unit was central to this Israeli mission.

Specific Data Collection

SR teams may be assigned to observe and measure specific site or enemy facility information as done for targeting, but in this case for ground operations rather than suppression by fire. Regular ground forces, for example, might need a road and bridge surveyed to know whether heavy vehicles can cross it. The SR may be able help with observation, photography, and other measurements. An engineering specialist, preferably from a special operations organization may need to augment the team.

SR commanders need to ensure such missions cannot be performed by organic reconnaissance and other elements of a maneuver force commander supported by the SR organization, as well as other supporting reconnaissance services such as IMINT.

For example, during the Falklands War of 1982, UK Special Air Service delivered using helicopters eight 4-man patrols deep into enemy-held territory up to 20 miles (32 km) from their hide sites several weeks before the main conventional force landings. Each man carried equipment needed for up to 25 days due to resupply limitations (cf. the 7-day limits of conventional LRS patrols discussed above). These patrols surveyed major centers of enemy activity. The patrols reconnoitered Argentinian positions at night, and then due to the lack of cover moved to distant observation posts (OPs). Information gathered was relayed to the fleet by secure radio not impervious from SIGINT that could locate their OPs. No common understanding of the threat of Argentine direction finding existed, and different teams developed individual solutions. The value of the information and the stress on the SR teams were tremendous. Their activities helped the force, limited in its sensors, develop an accurate operational picture of the opposition.[7]: 1–18

Offensive missions

SR units can engage targets of opportunity, but current doctrine emphasizes avoiding direct engagement, concentrating instead on directing air (e.g., GAPS as well as CAS), artillery, and other heavy fire support onto targets. The doctrine of bringing increasingly more accurate and potent firepower has however been evolving significantly since the early days of Vietnam.[14]

SR units are trained in target analysis which combines both engineer reconnaissance and special forces assessment to identify targets for subsequent attack by fire support, conventional units, or special operations (i.e., direct action or unconventional warfare behind enemy lines). They evaluate targets using the "CARVER" mnemonic:[19]

- Criticality: How important, in a strategic context, is the target? What effect will its destruction have on other elements of the target system? Is it more important to have real-time surveillance of the target (e.g., a road junction) than its physical destruction?

- Accessibility: Can an SR team reach or sense the target, keep it under surveillance for the appropriate time, and then exfiltrate after the target is struck?

- Recuperability: When the target is destroyed by fire support or direct action, in the case of DA missions, can the enemy repair, replace, or bypass it quickly using minimum resources? If so, it may not be a viable target.

- Vulnerability: do SR (including DA) and supporting units have the capability to destroy the target?

- Effect: Beyond pure military effect what are the political, economic, legal, and psychological effects of destroying the target? How would the attack affect local civilians?

- Recognizability: Can the target be recognized clearly, by SR and attack forces, under the prevailing weather, light, and in its terrain? If there are critical points within the target, they also must be recognizable by the means of destruction used.

Target acquisition

There are some differences between the general and the SR process of target acquisition: conventional units identify targets that directly affects the performance of their mission, while SR target acquisition includes identifying enemy locations or resources of strategic significance with a much wider scope. Examples of difficult strategic targets included Ho Chi Minh trail infrastructures and logistic concentrations, and the Scud hunt during Operation Desert Storm.[19]

SR units detect, identify, and locate targets to be engaged by lethal or nonlethal attack systems under the control of higher headquarters. SR also provides information on weather, obscuring factors such as terrain masking and camouflage, friendly or civilian presence in the target area, and other information that will be needed in targeting by independent attack systems.

During Operation Desert Storm, the US senior commanders, Colin Powell and Norman Schwarzkopf were opposed to using ground troops to search for Iraqi mobile SCUD launchers. Under Israeli pressure to send its own SOF teams into western Iraq and the realization that British SAS were already hunting SCUDs, US Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney proposed using US SR teams as well as SAS.[20] The senior British officer of the Coalition, Peter de la Billière was himself a former SAS commander and well-disposed to use SAS. While Schwarzkopf was known to generally oppose SOF, Cheney approved the use of US SOF to hunt for the launchers.[14]

On February 7, US SR teams joined British teams in the hunt for mobile Scud launchers.[21] Open sources contain relatively little operational information about U.S. SOF activities in western Iraq. Some basic elements have emerged, however. Operating at night, Air Force MH-53J Pave Low and Army MH-47E helicopters would ferry SOF ground teams and their specially equipped four-wheel-drive vehicles from bases in Saudi Arabia to Iraq.[22] The SOF personnel would patrol during the night and hide during the day. When targets were discovered, Air Force Combat Control Teams with the ground forces would communicate over secure radios to AWACS.

Directing fire support

SR, going back to Vietnam, was far more potent when it directed external firepower onto the target rather than engaging it with its own weapons. Early coordination between SR and air support in Vietnam depended on visual and voice communications, without any electronics to make the delivery precise. SR teams could throw colored smoke grenades as a visual reference, but they needed to be in dangerously close range to the enemy to do so. A slightly improved method involved their directing a Forward Air Controller aircraft to fire marking rockets onto the target, but the method was fraught with error.

In Vietnam, the support was usually aircraft-delivered, although in some cases the target might be in range of artillery. Today, the distance to which SR teams penetrate will usually be out of the range of artillery, but ground-launched missiles might support them. In either case, directing any support relies on one of two basic guidance paradigms:

- Go-Onto-Target (GOT) for moving targets,

- Go-Onto-Location-in-Space (GOLIS) for fixed targets

For close air support, the assumption had been that rapidly changing tactical situations, including sudden changes in geometry between friendly forces and the target, GOT was assumed. If the attack was to be guided from the ground, the target would be directly illuminated with some equivalent way of putting a virtual "hit me here" indication on the target, such as a laser designator.

Poststrike reconnaissance

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

Poststrike reconnaissance is the distant or close visual, photographic, and/or electronic surveillance of a specific point or area of operational or strategic significance that has been attacked to measure results. SR units carry out these missions when no other capabilities, such as conventional ground forces, local scouts and aviation, UAVs and other systems under the control of higher headquarters, and national-level intelligence collection capabilities cannot obtain the needed information.

Operational techniques

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

Their mission is not to engage in direct combat. It may be to observe and report, or it may include directing air or artillery attacks on enemy positions. If the latter is the case, the patrol still tries to stay covert; the idea is that the enemy obviously knows they are being attacked, but not who is directing fire.

While it is rare for a single man to do a special reconnaissance mission, it does happen. More commonly, the smallest unit is a two-man sniper team. Even though snipers teams' basic mission is to shoot enemy personnel or equipment, they are skilled in concealment and observation, and can carry out pure reconnaissance missions of limited durations. The US Marine Corps often detaches sniper teams organic to combat units, to establish clandestine observation posts.

Marine Force Recon Greenside Operations are those in which combat is not expected. US Army Special Forces SR operations commonly are built around 12-man "A detachments" or 6-man "split A detachments" and US Army Long Range Surveillance Teams are 6-man teams. UK Special Air Service operations build up from four-man units.

Infiltration

Special reconnaissance teams, depending on training and resources, may enter the area of operations in many ways. They may stay behind, where the unit deliberately stays hidden in an area that is expected to be overrun by advancing enemy forces. They may infiltrate by foot, used when the enemy does not have full view of his own lines, such that skilled soldiers can move through their own front lines and, as a small unit, penetrate those of the enemy. Such movement is most often by night.

They may have mechanical help on the ground, such as tactical four-wheel-drive vehicles (e.g., dune buggies or long-wheelbase Land Rovers) or motorcycles. The British Special Air Service pioneered in vehicle SR, going back to North Africa in World War II. In Desert Storm, US SR forces used medium and heavy helicopters to carry in vehicles for the Scud Hunt.

US Army Special Forces units working with the Afghan Northern Alliance did ride horses, and there may be other pack or riding animals capabilities.

SR units can move by air. They can use a variety of helicopter techniques, using fast disembarking by rope, ladder, or fast exit, at night. Alternatively, they can parachute, typically by night, and using the HALO or HAHO jump technique so their airplane does not alert the enemy.

Appropriately trained and equipped SR personnel can come by sea. They can use boats across inland water or from a surface ship or even a helicopter-launched boat. Another option is underwater movement, by swimming or delivery vehicle, from a submarine or an offshore surface ship. Some highly trained troops, such as United States Navy SEALs or British Special Boat Service or Indian MARCOS may parachute into open water, go underwater, and swim to the target.

Support

Units on short missions may carry all their own supplies, but, on longer missions, will need resupply. Typically, SR units are used to the area of operations, and are quite comfortable with local food if necessary. Because even the most secure radios can be detected and located—albeit by technical advanced airborne or spaceborne receivers—it is good practice to make transmissions as short and precise as possible. One way of shortening messages is to define a set of codes, typically two-letter, for various prearranged packages of equipment. Those starting with "A" might be for ammunition, "F" for food, and "M" for medical. Burst transmission is another radio security technique.

When long-range or long-duration patrols need resupply, a variety of techniques are used, all involving tradeoffs of security, resupply platform range and stealth, and the type and amount of resupply needed. When the SR patrol is in an area where the enemy knows there might be some patrol activity, helicopters may make a number of quick touchdowns, all but one simply to mislead the enemy. If it is reasonably certain that the enemy knows some patrols are present, but not where, the helicopters may even make some touchdowns more likely to be observed, but leave boobytrapped supplies.

They may need to have wounded personnel replaced, and sometimes evacuated. In some extreme situations, and depending strongly on the particular organization, wounded personnel who cannot travel may be killed by their own side, to avoid capture, with potential interrogation, perhaps under torture, and compromise of the special reconnaissance mission. Killing wounded personnel is described as a feature of Soviet and Russian Spetsnaz doctrine.[6] A variant described for US personnel was explained to a US forward air controller, by a MACV SOG officer,

"If I decide that there's no way we can effect your rescue [in Cambodia], I’ll order the gunships to fire at you to prevent the enemy from getting their hands on you. I can’t risk having any of the [recon] teams compromised if they take you alive."[15]: 304–305

Exfiltration

Most of the same methods used to infiltrate may be used to exfiltrate. Stay-behind forces may wait until friendly forces arrive in their area.

One of the more common means of exfiltration is by special operations helicopters. There are a number of techniques that do not require the helicopter to land, in which the SR team clips harnesses to ropes or rope ladders, and the helicopter flies away to an area where it is safe for them to come aboard. Small helicopters, such as the MH-6, have benches outside the cabin, onto which trained soldiers can quickly jump and strap in.

Communications and electronics

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

Without modern military electronics, and occasionally civilian ones, modern SR is fundamentally different from special soldiers that took on such risky missions but with unreliable communications and a constant danger of being located through them. Human-to-human electronics are not the only critical advance. Navigational systems such as GPS, with backups to them, have immense value. GPS tells the patrol its location, but laser rangefinders and other equipment can tell them the exact location of a target to send to a fire support unit. Strong encryption, electronic counter-countermeasures, and mechanisms, such as burst transmission to reduce the chance of being located all play a role.

Current trends in secure communications, light and flexible enough for SR patrols to carry, are based on the evolving concept of software defined radio. The immensely flexible Joint Tactical Radio System (JTRS) is deployed with NATO special operations units, and can provide low-probability-of-intercept encrypted communications between ground units, from ground to aircraft, or from ground to satellite. It lets a SR team use the same radio to operate on several networks, also allowing a reduced number of spare radios. Some of the raiders on the Son Tay raid carried as many as five radios.

JTRS closely integrates with target designators that plug into it, so that a separate radio is not required to communicate with precision-guided munition launchers. While unmanned aerial vehicles obviously involve more technologies than electronics, the availability of man-portable UAVs for launch by the patrol, as well as communications between the patrol and a high-performance UAV, may result in fundamentally new tactical doctrines.

Software defined radio, along with standard information exchange protocols such as JTIDS Link 16, are enabling appropriate communications and situation awareness, reducing the chance of fratricide, across multiple military services. The same basic electronic device[23] can be an Air Force Situation Awareness Data Link (SADL) device that communicates between aircraft doing close air support, but also can exchange mission data with Army Enhanced Position Location Reporting System (EPLRS) equipment. Again, the same basic equipment interconnects EPLRS ground units.

Reporting during and after the mission

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

The debriefing may be done by HUMINT officers of their own organization, who are most familiar with their information-gathering techniques. Information from SR patrols is likely to contribute to HUMINT collection, but, depending on the mission, may also contribute to IMINT, TECHINT, SIGINT, and MASINT Some of those techniques may be extremely sensitive and held on a need-to-know basis within the special reconnaissance organization and the all-source intelligence cell.

SR personnel generally report basic information, which may be expressed with the "SALUTE" mnemonic

- Size

- Activity

- Location

- Unit

- Time

- Equipment. They will provide map overlays, photography, and, when they have UAV/IMINT, SIGINT or MASINT augmentation, sensor data.

SR troops, however, also are trained in much more advanced reporting, such as preparing multiple map overlays of targets, lines of communications, civilian and friendly concentrations, etc. They can do target analysis, and also graph various activities on a polar chart centered either on an arbitrary reference or on the principal target.

Example units

Many countries have units with an official special reconnaissance role, including:

- Australia:

- Brazil

- Parachute Infantry Brigade (Brigada de Infantaria Pára-quedista)

- Special Operations Command (Comando de Operações Especiais)

- Marine Special Operations Battalion (Batalhão de Operações Especiais de Fuzileiros Navais, Batalhão Tonelero)

- Canada:

- Denmark:

- Jægerkorpset

- Frømandskorpset

- Sirius Patrol (two-man arctic patrols)

- Special Support and Reconnaissance Company.

- France:

- India:

- Ireland:

- Israeli:

- Italy:

- New Zealand:

- Poland:

- Portugal:

- Tropas de Operações Especiais (Special Operations Troops)

- Precursores Aeroterrestres (Air-Land Pathfinders)

- Destacamento de Ações Especiais (Naval Special Actions Detachment)

- Russia:

- Federal Security Service "FSB"

- Alpha Group Directorate "A" of the FSB Special Purpose Center (TsSN FSB), is an elite, stand-alone sub-unit of Russia's special forces.

- Vympel Group Directorate "B" Vympel Group is an elite Russian spetsnaz unit under the command of the FSB.(TsSN FSB)

- Armed Forces of the Russian Federation

- Spetsnaz GRU 2nd, 3nd, 10nd, 14nd, 16nd, 24nd, 25nd Spetsnaz Brigade (obrSpN)

- 45th Detached Reconnaissance Regiment Specnaz VDV (orpSpN)

- Russian commando frogmen 42nd, 420nd, 431nd, 561nd Naval Reconnaissance Spetsnaz Point (omrpSpN)

- Razvedka"Military intelligence" personnel/units within larger formations in ground troops, airborne troops and marines. Intelligence battalion in the divisions, reconnaissance company in the brigade, a reconnaissance platoon in the regiment. The level of training that the same Spetsnaz GRU but not controlled by the GRU, mascot bat

- Federal Security Service "FSB"

- Sri Lanka:

- Sweden:

- Särskilda Operationsgruppen (Special Operations Task Group)

- United Kingdom:

- United States:

- United States Air Force

- United States Army

- United States Army 1st Special Forces Operational Detachment-Delta (Airborne) (1st SFOD-D) / "Delta Force"

- United States Army 75th Ranger Regiment (United States Army Rangers)

- United States Army 75th Ranger Regiment, Regimental Reconnaissance Company (RRC)

- United States Army Battlefield Surveillance Brigades (BfSBs)

- United States Army BfSB Reconnaissance & Surveillance Squadrons (R&S Squadrons)

- United States Army Long-Range Surveillance (LRS) Units

- United States Army LRS Companies

- United States Army LRS Detachments

- United States Army LRS Teams

- United States Army LRS Detachments

- United States Army LRS Companies

- United States Army Long-Range Surveillance (LRS) Units

- United States Army BfSB Reconnaissance & Surveillance Squadrons (R&S Squadrons)

- United States Army Intelligence Support Activity (USAISA) / "The Activity"

- United States Army Special Forces ("Green Berets")

- United States Intelligence Community

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Paramilitary Operations (CIA Special Activities Division (SAD), Special Operations Group (SOG))

- United States Marine Corps

- United States Marine Corps Division Reconnaissance (Division Reconnaissance / Division Recon)

- United States Marine Corps Force Reconnaissance (Force Reconnaissance / Force Recon / FORECON)

- United States Marine Corps Light Armored Reconnaissance (LAR) Battalions

- United States Marine Corps Radio Reconnaissance Platoons

- United States Marine Corps Scout Sniper Platoons

- United States Marine Corps Surveillance and Target Acquisition (STA) Platoons

- United States Marine Raider Regiment (United States Marine Raiders)

- United States Navy

See also

- HUMINT

- Intelligence collection management

- List of intelligence gathering disciplines

- MASINT

- Special Activities Division

- SEAL Team Six

References

- ^ a b William J. Perry. "1996 Annual Defense Report, Chapter 22, Special Operations Forces". Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land, Article 29". International Red Cross. 18 October 1907. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ a b "Fourth Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War. Geneva, 12 August 1949, Article 29". International Red Cross. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ Ankony, Robert C., Lurps: A Ranger's Diary of Tet, Khe Sanh, A Shau, and Quang Tri, revised ed., Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Lanham, MD (2009)

- ^ Department of the Army. Field Manual 7-93 - Long-Range Surveillance Unit Operations Reconnaissance and Surveillance Units.

- ^ a b Suvorov, Viktor (1990). SPETSNAZ: The Inside Story Of The Special Soviet Special Forces. Pocket. ISBN 0-671-68917-7.

- ^ a b c d "Field Manual 31-20-5 - Special Reconnaissance Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Special Forces". 7 March 1990. FM 31-20-5. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ "U.S. Marine Corps Forces, Special Operations Command(MARSOC)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-16. Retrieved 2007-11-17.

- ^ "FM 3-05.102 Army Special Forces Intelligence" (PDF). July 2001.

- ^ L3/Linkabit Communications. "The AN/PRD-13 (V1) Man Portable Signal Intelligence System".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "18 (UKSF) Signals Regiment". Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ^ "TASK FORCE BLACK". Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ^ Department of the Army (30 September 1991). "4: Intelligence and Electronic Warfare Support to Special Forces Group (Airborne)". FM 34-36: Special Operations Forces Intelligence and Electronic Warfare Operations.

- ^ a b c Rosenau, William (2000). "Special Operations Forces and Elusive Enemy Ground Targets: Lessons from Vietnam and the Persian Gulf War. U.S. Air Ground Operations Against the Ho Chi Minh Trail, 1966-1972" (PDF). RAND Corporation. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Haas, Michael E. (1997). "Apollo's Warriors: US Air Force Special Operations during the Cold War" (PDF). Air University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2004. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ John T. Correll (November 2004). "Igloo White". Air Force Magazine. 87 (11). Archived from the original (– Scholar search) on September 30, 2007.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format=|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ CACI (9 April 2002). "AN/GSQ-187 Improved Remote Battlefield Sensor System (I-REMBASS)". Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ^ a b c Paul, James. "Operation Biting, Bruneval, 27th/28th Feb. 1942". Paul. Retrieved 2007-11-10.

- ^ a b Joint Chiefs of Staff (1993). "Joint Publication 3-05.5: Special Operations Targeting and Mission Planning Procedures" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R.; Trainor, Bernard E. (1995). The Generals’ War: The Inside Story of the Conflict in the Gulf. Little, Brown and Company.

- ^ Ripley, Tim. "Scud Hunting: Counter-force Operations against Theatre Ballistic Missiles" (PDF). Centre for Defence and International Security Studies, Lancaster University. Retrieved 2007-11-11.

- ^ Douglas C. Waller (1994). The Commandos: The Inside Story of America's Secret Soldiers. Dell Publishing.

- ^ "Joint Combat ID through Situation Awareness". Retrieved 2010-08-05.

External links

- Long Range Surveillance: True test for ‘quiet professional’

- Eyes Behind the Lines: US Army Long-Range Reconnaissance and Surveillance Units

- US Army Field Manual 7-93 Long Range Surveillance Unit Operations. (FM 7-93)

- PDF downloadable version of the US Army’s Long Range Surveillance Unit Operations Field Manual. (FM 7-93) This manual provides doctrine, tactics, techniques, and procedures on how Long Range Surveillance Units perform combat operations as a part of the Army's new Battlefield Surveillance Brigades.

- LRSU: EYES OF THE COMMANDER by Staff Sergeants Brent W. Dick and Kevin M. Lydon

- "Riding With the Posse Part I" by Mike Gifford

- International Special Training Center and NATO celebrate 30 years of teaching special forces (July 2, 2009) by Maj. Jennifer Johnson, 7th Army Joint Multinational Training Command Public Affairs