State Duma (Russian Empire)

State Duma Госуда́рственная ду́ма Gosudarstvennaya Duma | |

|---|---|

| Parliament of the Russian Empire | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

| Seats | 434 – 518 |

| Elections | |

Last election | September 1912 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Tauride Palace St. Petersburg | |

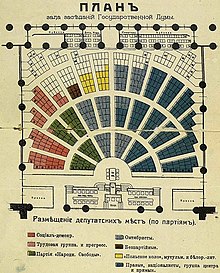

The State Duma or Imperial Duma was a legislative assembly in the late Russian Empire, which held its meetings in the Taurida Palace in St. Petersburg. It was convened four times between 27 April 1906 and the collapse of the Empire in February 1917. The First and the Second Dumas were more democratic and represented a greater number of national types than their successors.[1] The Fourth Duma was dissolved on 6 October 1917.

History

Coming under pressure from the Russian Revolution of 1905, on August 6, 1905 (O.S.), Sergei Witte (appointed by Nicholas II to manage peace negotiations with Japan) issued a manifesto about the convocation of the Duma, initially thought to be a purely advisory body, the so-called Bulygin-Duma. In the subsequent October Manifesto, the Tsar promised to introduce further civil liberties, provide for broad participation in a new "State Duma", and endow the Duma with legislative and oversight powers. The State Duma was to be the lower house of a parliament, and the State Council of Imperial Russia the upper house.

However, Nicholas II was determined to retain his autocratic power (in which he succeeded). On April 23, 1906 (O.S.), the Tsar issued the Fundamental Laws, which gave him the title of "supreme autocrat". Although no law could be made without the Duma's assent, neither could the Duma pass laws without the approval of the noble-dominated State Council (half of which was to be appointed directly by the Tsar), and the Tsar himself retained a veto. The laws stipulated that ministers could not be appointed by, and were not responsible to, the Duma, thus denying responsible government at the executive level. Furthermore, the Tsar had the power to dismiss the Duma and announce new elections whenever he wished; article 87 allowed him to pass temporary (emergency) laws by decrees. All these powers and prerogatives assured that, in practice, the Government of Russia continued to be a non-official Absolute Monarchy. It was in this context that the first Duma opened four days later, on April 27.[2]

First Duma

The first Duma opened with around 500 deputies; most radical left parties, such as the Socialist Revolutionary Party had boycotted the election, leaving the moderate Constitutional Democrats (Kadets) with the most deputies (around 180). Second came an alliance of slightly more radical leftists, the Trudoviks (Laborites) with around 100 deputies. To the right of both were a number of smaller parties, including the Octobrists. Together, they had around 45 deputies. Other deputies, mainly from peasant groups, were unaffiliated.[2]

The Kadets were among the only political parties capable of consistently drawing voters due to their relatively moderate political stance. The Kadets drew from an especially urban population, often failing to draw the attention of rural communities who were instead committed to other parties.[3]

The Duma ran till 8 July 1906, with little success.[4] The Tsar and his loyal Prime Minister Ivan Goremykin were keen to keep it in check, and reluctant to share power; the Duma, on the other hand, wanted continuing reform, including electoral reform, and, most prominently, land reform.[2] Sergei Muromtsev, Professor of Law at Moscow University, was elected Chairman.[5] Lev Urusov held a famous speech.[6] Scared by this liberalism, the Tsar dissolved the Duma, reportedly saying 'curse the Duma. It is all Witte's doing'. The same day, Pyotr Stolypin was named as the new Prime Minister.[2]

In frustration, Paul Miliukov and approximately 200 deputies, mostly from the liberal Kadets party decamped to Vyborg, then part of Russian Finland, to discuss the way forward. From there, they issued the Vyborg Appeal, which called for civil disobedience. Largely ignored, it ended in their arrest and the closure of Kadet Party offices. This, among other things, helped pave the way for an alternative makeup for the second Duma.[2]

Second Duma

The Second Duma (20 February 1907 to 2 June 1907) was equally short-lived.[4] One of the new members was Vladimir Purishkevich, strongly opposed to the October Manifesto. The Bolsheviks and Mensheviks (that is, both factions of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party) and the Socialist Revolutionaries all abandoned their policies of boycotting elections to the Duma, and consequently won a number of seats. The Kadets (by this point the most moderate and centrist party), found themselves outnumbered two-to-one by their more radical counterparts. Even so, Stolypin and the Duma could not build a working relationship, being divided on the issues of land confiscation (which the socialists and, to a lesser extent, the Kadets, supported but the Tsar and Stolypin vehemently opposed) and Stolypin's brutal attitude towards law and order.[2]

On June 1, 1907, prime minister Pyotr Stolypin accused Social Democrats of preparing an armed uprising and demanded that the Duma exclude 55 Social Democrats from Duma sessions and strip 16 of their parliamentary immunity. When this ultimatum was rejected by Duma, it was dissolved on 3 June by an ukase (imperial decree) in what became known as the Coup of June 1907.[7]

The Tsar was unwilling to be rid of the State Duma, despite these problems. Instead, using emergency powers, Stolypin and the Tsar changed the electoral law and gave greater electoral value to the votes of landowners and owners of city properties, and less value to the votes of the peasantry, whom he accused of being "misled", and, in the process, breaking his own Fundamental Laws.[2]

Third Duma

This ensured the third Duma (7 November 1907 – 9 June 1912) would be dominated by gentry, landowners and businessmen. The number of deputies from non-Russian regions was greatly reduced.[8] The system facilitated better, if hardly ideal, cooperation between the Government and the Duma; consequently, the Duma lasted a full five-year term, and succeeded in 200 pieces of legislation and voting on some 2500 bills. Due to its more noble, and Great Russian composition, the third Duma, like the first, was also given a nickname, "The Duma of the Lords and Lackeys" or "The Master's Duma". The Octobrist party were the largest, with around one-third of all the deputies. This Duma, less radical and more conservative, left clear that the new electoral system would always generate a landowners-controlled Duma, which in turn would be under complete submission to the Tsar, unlike the first two Dumas.[2]

In terms of legislation, the Duma supported an improvement in Russia's military capabilities, Stolypin's plans for land reform and basic social welfare measures. The power of Nicholas' hated land captains was consistently reduced. It also supported more regressive laws, however, such as on the question of Finnish autonomy and Russification, with a fear of the Empire breaking up being prevalent. Since the dissolution of the Second Duma a very large proportion of the Empire was either under martial law, or one of the milder forms of the state of siege. It was forbidden, for instance, at various times and in various places, to refer to the dissolution of the Second Duma, to the funeral of the Speaker of the First Duma, Muromtsev, and the funeral of Leo Tolstoy, to the fanatical [right-wing] monk Iliodor, or to the notorious agent provocateur, Yevno Azef.[9] Stolypin was assassinated in September 1911 and replaced by his Finance Minister Vladimir Kokovtsov.[2] It enabled Count Kokovtsov to balance the budget regularly and even to spend on productive purposes.

Fourth Duma

The Fourth Duma of 15 November 1912 – 6 October 1917 was also of limited political influence. Twice it went into recess, for five months and for almost eight months. There was one promising new member in Alexander Kerensky, but also Roman Malinovsky, a Bolshevik. In March 1913 the Octobrists, led by Alexander Guchkov, President of the Duma, commissioned an investigation on Grigori Rasputin to research the allegations being a Khlyst.[10] The leading party of the Octobrists divided itself into three different sections.

On the eve of the war the government and the Duma were hovering round one another like indecisive wrestlers, neither side able to make a definite move.[11] On July 1, 1914 the Tsar suggested that the Duma should be reduced to merely a consultative body. The war made the political parties more cooperative and practically formed into one party. When the Tsar pronounced to leave for the front in Mogilev, the Progressive Bloc was formed, fearing Rasputin's influence over Tsarina Alexandra would increase.[12]

In August 1914 the Duma volunteered its own dissolution until the end of the war, but on 17 July 1915 it reconvened for six weeks. Its former members became increasingly displeased with Tsarist control of military and governmental affairs and demanded its own reinstatement. When the Tsar refused its call for the replacement of his cabinet on 21 August with a "Ministry of National Confidence", roughly half of the deputies formed a "Progressive Bloc", which in 1917 became a focal point of political resistance. On 3 September 1915 the Duma prorogued.[4]

The Duma gathered on 9 February 1916 after the 76-year-old Ivan Goremykin had been replaced by Boris Stürmer as prime minister. The deputies were disappointed when Stürmer held his speech. Because of the war, he said, it wasn't the time for constitutional reforms. For the first time in his life, the Tsar made a visit to the Taurida Palace, which made it practically impossible to hiss at the new prime minister.

On 1 November 1916 (Old Style) the Duma reconvened and the government under Boris Stürmer[13] was attacked by Pavel Milyukov in the State Duma, not gathering since February. In his speech he spoke of "Dark Forces", and highlighted numerous governmental failures with the famous question "Is this stupidity or treason?" Kerensky called the ministers "hired assassins" and "cowards" and said they were "guided by the contemptible Grishka Rasputin!"[14]

For the Octobrists and the Kadets, who were the liberals in the parliament, Rasputin and his support of autocracy and absolute monarchy was one of their main obstacles. The politicians tried to bring the government under control of the Duma.[15] "To the Okhrana it was obvious by the end of 1916 that the liberal Duma project was superfluous, and that the only two options left were repression or a social revolution."[16]

On 19 November Vladimir Purishkevich, one of the founders of the Black Hundreds, gave a speech in the Duma. He declared the monarchy had become discredited because of what he called the "ministerial leapfrog".[17][18]

In the seventeen months of the "Tsarina's rule", from September 1915 to February 1917, Russia had four Prime Ministers, five Ministers of the Interior, three Foreign Ministers, three War Ministers, three Ministers of Transport and four Ministers of Agriculture. This "ministerial leapfrog", as it came to be known, not only removed competent men from power, but also disorganized the work of government since no one remained long enough in office to master their responsibilities.[19]

On 14 February 1917 the Duma reconvened.[4] During the 1917 February Revolution, a group of Duma members formed the Provisional Committee. Guchkov, along with Vasily Shulgin, came to the army headquarters near Pskov to persuade the Tsar to abdicate. The committee sent commissars to take over ministries and other government institutions, dismissing Tsar-appointed ministries and later formed the Provisional Government under Georgi Lvov.

Seats held in Imperial Dumas

| Party | First Duma | Second Duma | Third Duma | Fourth Duma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russian Social Democratic Party | 18 (Mensheviks) | 47 (Mensheviks) | 19 (Bolsheviks) | 15 (Bolsheviks) |

| Socialist-Revolutionary Party | – | 37 | – | – |

| Labour group | 136 | 104 | 13 | 10 |

| Progressist Party | 27 | 28 | 28 | 41 |

| Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets) | 179 | 92 | 52 | 57 |

| Non-Russian National Groups | 121 | – | 26 | 21 |

| Centre Party | – | – | – | 33 |

| Octobrist Party | 17 | 42 | 154 | 95 |

| Nationalists | 60 | 93 | 26 | 22 |

| Rightists | 8 | 10 | 147 | 154 |

| TOTAL | 566 | 453 | 465 | 448 |

Chairmen of the State Duma of the Russian Empire

- Sergey Muromtsev (1906)

- Fyodor Golovin (1907)

- Nikolay Khomyakov (1907–1910)

- Alexander Guchkov (1910–1911)

- Mikhail Rodzianko (1911–1917)

Deputy Chairmen of the State Duma of the Russian Empire

- The First Duma

- Prince Pavel Dolgorukov (Cadet Party) 1906

- Nikolay Gredeskul (Cadet Party) 1906

- The Second Duma

- N.N. Podznansky (Left) 1907

- M.E. Berezik (Trudoviki) 1907

- The Third Duma

- Vol. V.M. Volkonsky (moderately right), bar. A.F. Meyendorff (Octobrist), C.J. Szydlowski (Octobrist), M. Kapustin (Octobrist), I. Sozonovich (right).

- The Fourth Duma

- Prince D.D. Urusov (Progressive Bloc)

- + Prince V.M. Volkonsky (Centrum-Right) (1912–1913)

- Nikolay Nikolayevich Lvov (Progressive Bloc) (1913)

- Alexander Konovalov (Progressive Bloc) (1913–1914)

- S.T. Varun-Sekret (Octobrist Party) (1913–1916)

- Alexander Protopopov (Left Wing Octobrist Party) (1914–1916)

- Nikolai Vissarionovich Nekrasov (Cadet Party) (1916–1917)

- Count V.A. Bobrinsky (Nationalist) (1916–1917)

- Prince D.D. Urusov (Progressive Bloc)

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

- ^ Harold Whitmore Williams (1915) Russia of the Russians, p. 82

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Walter Gerald Moss (1 October 2004). A History Of Russia: Since 1855. Anthem Press. pp. 97–106. ISBN 978-1-84331-034-1. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Thatcher, Ian (2011). "The First State Duma, 1906: The View from the Contemporary Pamphlet and Monograph Literature". Canadian Journal of History.

- ^ a b c d Inevitable?: Turning Points of the Russian Revolution by Tony Brenton

- ^ Abraham Ascher, "P.A. Stolypin: The Search for Stability in Late Imperial Russia", Stanford, 2001, p. 102

- ^ Mikhail Larionov and the Cultural Politics of Late Imperial Russia by Sarah Warren, p. 64. [1]

- ^ Vladimir Gurko (1939) Features and Figures of the Past. Government and Opinion in the Reign of Nicholas II, p. 8. [2]

- ^ Harold Whitmore Williams (1915) Russia of the Russians, p. 78

- ^ Harold Whitmore Williams (1915) Russia of the Russians, p. 102, 105

- ^ B. Moynahan (1997) Rasputin. The saint who sinned, p. 169-170.

- ^ G.A. Hosking (1973) The Russian constitutional experiment. Government and Duma, 1907-1914, p. 205.

- ^ O. Figes (1996) A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution, 1891–1924, p. 270.

- ^ Alexanderpalace

- ^ The Russian Provisional Government, 1917: Documents, Volume 1, p. 16 by Robert Paul Browder, Aleksandr Fyodorovich Kerensky [3]

- ^ O. Antrick, (1938) "Rasputin und die politischen Hintergründe seiner Ermordung", p. 79, 117.

- ^ O. Figes (1996), p. 811.

- ^ O. Figes (1997) A People's Tragedy: A History of the Russian Revolution, p. 278. [4]

- ^ The Cambridge History of Russia: Volume 2, Imperial Russia, 1689-1917, p. 668 by Maureen Perrie, Dominic Lieven, Ronald Grigor Suny [5]

- ^ http://www.johndclare.net/Russ_Rasputin_Figes.htm