Doping in American football

| Part of a series on |

| Doping in sport |

|---|

|

National Football League (NFL). The NFL began to test players for steroid use during the 1987 season, and started to issue suspensions to players during the 1989 season.[1] The NFL has issued as many as six random drug tests to players, with each player receiving at least one drug test per season.[2] One notable incident was when in 1992, defensive end Lyle Alzado died from brain cancer, which was attributed to the use of anabolic steroids,[3] however, Alzado's doctors stated that anabolic steroids did not contribute to his death.[4]

The use of performance-enhancing drugs has also been found in other levels of football, including college level, and high school.[5] The most recent figures from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) football drug tests show that one percent of all NCAA football players failed drug tests taken at bowl games, and three percent have admitted to using steroids overall.[5] In the NCAA, players are subject to random testing with 48 hours notice, and are also randomly tested throughout the annual bowl games.[5] The NCAA will usually take approximately 20 percent of the players on a football team to test on a specific day.[5]

Anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs are also used throughout high school football. Steroid use at this level of play doubled from 1991 to 2003, with results of a survey showing that about 6 percent of players out of the 15,000 surveyed had admitted to using some type of anabolic steroid or performance-enhancing drug at one point in their playing time.[6] Other data shows that only 4 percent of high schools have some form of drug testing program in place for their football teams.[6]

Use in the NFL

The use of performance-enhancing drugs and anabolic steroids dates back to the late 1960s in the National Football League (NFL). The case of Denver Broncos defensive lineman Lyle Alzado notably exposed early use among NFL players. In the last years of his life, as he battled against the brain tumor that eventually caused his death at the age of 43, Alzado asserted that his steroid abuse directly led to his fatal illness, but his physician stated it could not possibly be true. Alzado recounted his steroid abuse in an article in Sports Illustrated. He said:

I started taking anabolic steroids in 1969 and never stopped. It was addicting, mentally addicting. Now I'm sick, and I'm scared. Ninety percent of the athletes I know are on the stuff. We're not born to be 300 lbs or jump 30ft. But all the time I was taking steroids, I knew they were making me play better. I became very violent on the field and off it. I did things only crazy people do. Once a guy sideswiped my car and I beat the hell out of him. Now look at me. My hair's gone, I wobble when I walk and have to hold on to someone for support, and I have trouble remembering things. My last wish? That no one else ever dies this way."[7]

Former player and NFL coach Jim Haslett said in 2005 that during the 1980s, half of the players in the league used some type of performance-enhancing drug or steroid and all of the defensive lineman used them. One of the players from the Super Bowl winning 1979 Pittsburgh Steelers team who had earlier confessed to using steroids (in a 1985 Sports Illustrated article) was offensive lineman Steve Courson.[8] Courson blamed a heart condition that he developed on steroids. However, Courson also said that some of his teammates, such as Jack Ham and Jack Lambert, refused to use any kind of performance-enhancing drug.[8]

The BALCO Scandal in 2003 also revealed many users of steroids in the NFL. The scandal followed a US Federal government investigation of the Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative (BALCO) into accusations of its supplying anabolic steroids to professional athletes.[9] U.S. sprint coach Trevor Graham had given an anonymous phone call to the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) in June 2003 accusing a number of athletes being involved in doping with a steroid that was not detectable at the time. He named BALCO owner Victor Conte as the source of the steroid. As evidence, Graham delivered a syringe containing traces of a substance nicknamed The Clear.

Shortly after, then-director of the UCLA Olympic Analytical Laboratory Don Catlin, developed a testing process for The Clear (tetrahydrogestrinone (THG)).[10] With the ability to detect THG, the USADA retested 550 existing urine samples from athletes, of which several proved to be positive for THG.[11]

A number of players from the Oakland Raiders were implicated in this scandal, including Bill Romanowski, Tyrone Wheatley, Barrett Robbins, Chris Cooper and Dana Stubblefield.[12] Recently, many players have confessed to steroid use. One of these players was former Oakland Raiders player Bill Romanowski. Romanowski confessed on the American news television show 60 Minutes to using steroids for a two-year period beginning in 2001.[13] He stated that these were supplied by former NFL player and former head of BALCO Victor Conte, saying:

I took [human growth hormone] for a brief period and ... I definitely didn't receive what I got out of THG."[13]

A notable recent occurrence happened in 2006. During the season, San Diego Chargers linebacker Shawne Merriman failed a drug test and was suspended for four games when his primary "A" sample and backup "B" sample both tested positive for a banned substance.[14] Merriman was named NFL Defensive Rookie of the Year in 2005, with 54 tackles and 10 sacks. He also had a total of five passes defended and two forced fumbles. He was a starting player in the 2005 Pro Bowl, and was a leader on his team in sacks in the 2006 season.[14] The incident led to the passage of a rule that forbids a player who tests positive steroids from being selected to the Pro Bowl in the year in which they tested positive. The rule is commonly referred to as the "Merriman Rule".[15][16] However, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell has tried to distance the policy from being associated with the player, stating that Merriman tested clean on 19 of 20 random tests for performance-enhancing drugs since entering the league.[17]

NFL steroid policy

The NFL banned substances policy has been acclaimed by some[18] and criticized by others,[19] but the policy is one of the longest running in professional sports, beginning in 1987.[18] Since the NFL started random, year-round tests and suspending players for banned substances, many more players have been found to be in violation of the policy. By April 2005, 111 NFL players had tested positive for banned substances, and of those 111, the NFL suspended 54.[19]

The policy involves all players getting tested times throughout the regular season, the playoffs, and during the off-season.[2] The policy was different in the 1990s than it is today, due to heavy criticism from the United States Government.[19] Originally, there were specific guidelines for when the player was caught using a steroid or other performance-enhancing drug. If a player was caught using steroids during training camp or some other off-season workout, they were suspended for 30 days for a first-time offense.[2] Typically, this would mean missing four games, three in the pre-season and one in the regular season. Players would then be tested throughout the year for performance-enhancing drugs and steroids. A player who tested positively during a previous test might or might not be included in the next random sampling.[2] A player who tested positive again would be suspended for one year, and a suspension for a third offense was never specified, because it never happened.[2] In later years when many players ignored the policy, NFLPA director Gene Upshaw sent out a letter to all NFL players that stated:

"Over the past few years, we have made a special effort to educate and warn players about the risks involved in the use of "nutritional supplements." Despite these efforts, several players have been suspended even though their positive test result may have been due to the use of nutritional supplements. Under the Policy, you and you alone are responsible for what goes into your body. As the Policy clearly warns, supplements are not regulated or monitored by the government. This means that, even if they are bought over-the-counter from a known establishment, there is simply no way to be sure that they:

(a) contain the ingredients listed on the packaging;

(b) have not been tainted with prohibited substances; or

(c) have the properties or effects claimed by the manufacturer or salesperson.Therefore, if you take these products, you do so AT YOUR OWN RISK! The risk is at least a 4-game suspension without pay if a prohibited substance is detected in your system. For your own health and success in the League, we strongly encourage you to avoid the use of supplements altogether, or at the very least to be extremely careful about what you choose to take."[20]

Use in college football

Steroids and performance-enhancing drugs have been reportedly used by many college football players in the NCAA. According to a recent drug test and survey, about one percent of all NCAA football players have tested positive for a performance-enhancing drug or steroid, and about three percent have admitted to using one sometime during their college football career.[5] Controversy arose in 2005, when former Brigham Young University player Jason Scukanec, although never admitting to using steroids himself, stated that steroids were used in many notable Division I programs.[5]

Scukanec, who is the co-host of a sports talk radio show "Primetime With Isaac and Big Suke" on KFXX-AM (AM 1080 "The Fan") in Portland, Oregon, made these statements:

Over the course of my five years at BYU, I have concrete proof of 13 to 15 guys (using steroids), and I would suspect five others...And BYU is more temperate than most programs. Being around NFL and NFL Europe players, they would tell me stuff that blew my mind. I know other schools are worse. I would bet my house you could find at least five guys on every Division I team in the country (using steroids).[5]

My best friend was a steroid monster. I shot him up probably four times in the butt. He couldn’t do it himself. He was afraid of needles. He was naturally 245 or 250 pounds, but he got up to 312 with a 36-inch waist. He had stretch marks on his chest and shoulder and eventually blew out both of his knees. When I was with the Broncos, they brought him in for a workout. The offensive line coach came to me and said, ‘What’s your friend on?’ Another guy we played with, who is still in the NFL, would come back at the end of a season weighing 270. Three weeks into the offseason, he was 295 and buffed. It wasn’t a big mystery what he was doing. Three guys I played with in the NFL, I saw them use (steroids). The coaches knew the guys on the juice. To pretend it doesn’t go on would be a farce. It’s the big no-no nobody wants to talk about. And you don’t want to know what’s going on at the junior college level, where no testing is being done.[5]

Portland State University coach Tim Walsh commented on the situation, declining the remarks:

That’s a bold statement. It’s a tough accusation, to come up with a number like that. Is it true? Maybe, maybe not. I wish I could say I knew for sure. I’m not naive enough to think it’s not going on out there, but I feel pretty strongly it’s not been a problem with our players over the years.[5]

The number of players who have admitted using steroids in a confidential survey conducted by the NCAA since the 1980s has dropped from 9.7 percent in 1989 to 3.0 percent in 2003.[5] During the 2003 season, there were over 7,000 drug tests, with just 77 turning up as positive test results.[5] Scukanec claims that methods were used to get around the drug testing, whether it be avoiding the tests by using the drugs during the off-season, or flushing the drugs out of your system. This was used with a liquid he referred to as the "pink."[5] He stated:

There are a ton of (masking) products out there. What most of them cause is diuresis (increased excretion of urine), which means the athlete is providing diluted urine sample, almost water. In NCAA drug testing, the athlete is required to provide a concentrated specimen that passes a specific gravity cutoff. If the specimen is too diluted, he has to provide another sample. Using a product to cause diuresis is not going to help.[5]

Health issues

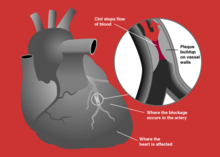

Performance-enhancing drugs, most notably anabolic steroids can cause many health issues. Many American football players have experienced these health issues from using anabolic steroids, which have even resulted in some player's deaths. Most of these issues are dose-dependent, the most common being elevated blood pressure, especially in those with pre-existing hypertension,[21] and harmful changes in cholesterol levels: some steroids cause an increase in LDL cholesterol and a decrease in HDL cholesterol.[22] Anabolic steroids such as testosterone also increase the risk of cardiovascular disease[23] or coronary artery disease.[24][25] Acne is fairly common among anabolic steroid users, mostly due to stimulation of the sebaceous glands by increased testosterone levels.[26][27] Conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) can accelerate the rate of premature baldness for those who are genetically predisposed.

Other side effects can include alterations in the structure of the heart, such as enlargement and thickening of the left ventricle, which impairs its contraction and relaxation.[28] Possible effects of these alterations in the heart are hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, heart attacks, and sudden cardiac death.[29] These changes are also seen in non-drug using athletes, but steroid use may accelerate this process.[30][31] However, both the connection between changes in the structure of the left ventricle and decreased cardiac function, as well as the connection to steroid use have been disputed.[32][33]

High doses of oral anabolic steroid compounds can cause liver damage as the steroids are metabolized (17α-alkylated) in the digestive system to increase their bioavailability and stability.[34] When high doses of such steroids are used for long periods, the liver damage may be severe and lead to liver cancer.[35][36]

There are also gender-specific side effects of anabolic steroids. Development of breast tissue in males, a condition called gynecomastia (which is usually caused by high levels of circulating estrogen), may arise because of increased conversion of testosterone to estrogen by the enzyme aromatase.[37] Reduced sexual function and temporary infertility can also occur in males.[38][39][40] Another male-specific side effect which can occur is testicular atrophy, caused by the suppression of natural testosterone levels, which inhibits production of sperm (most of the mass of the testes is developing sperm). This side effect is temporary: the size of the testicles usually returns to normal within a few weeks of discontinuing anabolic steroid use as normal production of sperm resumes.[41] Female-specific side effects include increases in body hair, deepening of the voice, enlarged clitoris, and temporary decreases in menstrual cycles. When taken during pregnancy, anabolic steroids can affect fetal development by causing the development of male features in the female fetus and female features in the male fetus.[42]

See also

- Steroid use in baseball

- Doping in the United States

- Doping (sport)

- List of suspensions in the National Football League

References

- ^ Gay, Nancy (27 October 2006). "Steroids spotlight turns to football". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Timothy (3 July 1991). "N.F.L.'s Steroid Policy Too Lax, Doctor Warns". New York Times. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ Puma, Mike. "Not the size of the dog in the fight". ESPN. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Real Sports, Lyle Alzado". elitefitness.com. Retrieved 2007-04-24.[dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Eggers, Kerry. "NCAA athletes on the juice?". Portland Tribune. Retrieved 2008-05-02.[dead link]

- ^ a b Livingstone, Seth (8 June 2005). "Fight against steroids gaining muscle in high school athletics". USA Today. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Lyle Alzado and Steroids". Usefultrivia.com. 2004. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Haslett says '70s Steelers made steroids popular in NFL". CBS SportsLine. 24 March 2005. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ Fainaru-Wada, Mark, and Lance Williams. Game Of Shadows. 2006.

- ^ Steeg, Jill Lieber (28 February 2007). "Catlin has made a career out of busting juicers". USA Today. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ Longman, Jere; Joe Drape (November 2, 2003). "Decoding a Steroid: Hunches, Sweat, Vindication". New York Times. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ Kimball, Bob; Dure, Beau (27 November 2007). "BALCO investigation time line". USA Today. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Romo tells '60 Minutes' he used steroids". ESPN.com. AP. 13 October 2005. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Sources: Chargers' Merriman suspended for steroids". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ^ Klis, Mike (2010-09-14). "Chargers LB supports the "Merriman Rule"". Denver Post. Retrieved 2012-11-01.

- ^ "Sources: Positive 'roids test to result in Pro Bowl ban". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ^ "Chargers LB tested clean 19 of 20 times". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ^ a b Maske, Mark; Shapiro, Leonard (2005-04-28). "NFL's Steroid Policy Gets Kudos on Capitol Hill". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ a b c "NFL Steroid Policy 'Not Perfect'". CBS News. 2005-04-27.

- ^ "NFl Banned Substances- Letter". Retrieved 2008-05-04. [dead link]

- ^ Grace F, Sculthorpe N, Baker J, Davies B (2003). "Blood pressure and rate pressure product response in males using high-dose anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS)". J Sci Med Sport. 6 (3): 307–12. doi:10.1016/S1440-2440(03)80024-5. PMID 14609147.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tokar, Steve (February 2006). "Liver Damage And Increased Heart Attack Risk Caused By Anabolic Steroid Use". University of California - San Francisco. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ Barrett-Connor, E. (1995). "Testosterone and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in men". Diabete Metab. 21 (3): 156–61. PMID 7556805.

- ^ Bagatell C, Knopp R, Vale W, Rivier J, Bremner W (1992). "Physiologic testosterone levels in normal men suppress high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels". Ann Intern Med. 116 (12 Pt 1): 967–73. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-116-12-967. PMID 1586105.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mewis C, Spyridopoulos I, Kühlkamp V, Seipel L (1996). "Manifestation of severe coronary heart disease after anabolic drug abuse". Clinical Cardiology. 19 (2): 153–5. doi:10.1002/clc.4960190216. PMID 8821428.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hartgens F, Kuipers H (2004). "Effects of androgenic-anabolic steroids in athletes". Sports Med. 34 (8): 513–54. doi:10.2165/00007256-200434080-00003. PMID 15248788.

- ^ Melnik B, Jansen T, Grabbe S (2007). "Abuse of anabolic-androgenic steroids and bodybuilding acne: an underestimated health problem". Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft=Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 5 (2): 110–7. doi:10.1111/j.1610-0387.2007.06176.x. PMID 17274777.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ De Piccoli B, Giada F, Benettin A, Sartori F, Piccolo E (1991). "Anabolic steroid use in body builders: an echocardiographic study of left ventricle morphology and function". Int J Sports Med. 12 (4): 408–12. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1024703. PMID 1917226.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sullivan ML, Martinez CM, Gallagher EJ (1999). "Atrial fibrillation and anabolic steroids". The Journal of emergency medicine. 17 (5): 851–7. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(99)00095-5. PMID 10499702.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dickerman RD, Schaller F, McConathy WJ (1998). "Left ventricular wall thickening does occur in elite power athletes with or without anabolic steroid Use". Cardiology. 90 (2): 145–8. doi:10.1159/000006834. PMID 9778553.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ George KP, Wolfe LA, Burggraf GW (1991). "The 'athletic heart syndrome'. A critical review". Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 11 (5): 300–30. doi:10.2165/00007256-199111050-00003. PMID 1829849.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dickerman R, Schaller F, Zachariah N, McConathy W (1997). "Left ventricular size and function in elite bodybuilders using anabolic steroids". Clin J Sport Med. 7 (2): 90–3. doi:10.1097/00042752-199704000-00003. PMID 9113423.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Salke RC, Rowland TW, Burke EJ (1985). "Left ventricular size and function in body builders using anabolic steroids". Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 17 (6): 701–4. doi:10.1249/00005768-198512000-00014. PMID 4079743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yamamoto Y, Moore R, Hess H, Guo G, Gonzalez F, Korach K, Maronpot R, Negishi M (2006). "Estrogen receptor alpha mediates 17alpha-ethynylestradiol causing hepatotoxicity". J Biol Chem. 281 (24): 16625–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.M602723200. PMID 16606610.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Socas L; Zumbado M; Pérez-Luzardo O; et al. (2005). "Hepatocellular adenomas associated with anabolic androgenic steroid abuse in bodybuilders: a report of two cases and a review of the literature". British journal of sports medicine. 39 (5): e27. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2004.013599. PMC 1725213. PMID 15849280.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Velazquez I, Alter BP (2004). "Androgens and liver tumors: Fanconi's anemia and non-Fanconi's conditions". Am. J. Hematol. 77 (3): 257–67. doi:10.1002/ajh.20183. PMID 15495253.

- ^ Marcus R, Korenman S (1976). "Estrogens and the human male". Annu Rev Med. 27: 357–70. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.27.020176.002041. PMID 779604.

- ^ Hoffman JR, Ratamess NA (June 1, 2006). "Medical Issues Associated with Anabolic Steroid Use: Are they Exaggerated?" (PDF). Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ^ Meriggiola, M.; Costantino, A.; Bremner, W.; Morselli-Labate, A. (2002). "Higher testosterone dose impairs sperm suppression induced by a combined androgen-progestin regimen". American Society of Andrology. 23 (5): 684–90. PMID 12185103.

- ^ Matsumoto, A. (1990). "Effects of chronic testosterone administration in normal men: safety and efficacy of high dosage testosterone and parallel dose-dependent suppression of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and sperm production". The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 70 (1): 282–7. doi:10.1210/jcem-70-1-282. PMID 2104626.

- ^ Alén M, Reinilä M, Vihko R (1985). "Response of serum hormones to androgen administration in power athletes". Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 17 (3): 354–9. doi:10.1249/00005768-198506000-00009. PMID 2991700.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Manikkam, M.; Crespi, E.; Doop, D.; et al. (2004). "Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone excess leads to fetal growth retardation and postnatal catch-up growth in sheep". Endocrinology. 145 (2): 790–8. doi:10.1210/en.2003-0478. PMID 14576190.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)