Svetozar Miletić

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

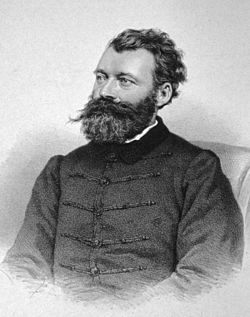

Svetozar Miletić Светозар Милетић | |

|---|---|

| |

| 27th Mayor of Novi Sad | |

| In office 1861–1862 | |

| Preceded by | Gavrilo Polzović |

| Succeeded by | Pavle Mačvanski |

| 30th Mayor of Novi Sad | |

| In office 1867–1868 | |

| Preceded by | Pavle Stojanović |

| Succeeded by | Pavle Stojanović |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 22 February 1826 Mošorin, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 4 February 1901 (aged 74) Vršac, Austria-Hungary |

Svetozar Miletić (Serbian Cyrillic: Светозар Милетић; 22 February 1826 – 4 February 1901) was an advocate, journalist, author, politician, mayor of Novi Sad, and the political leader of Serbs in Vojvodina.[1]

Family

Miletić's ancestor was Mileta Zavišić who came to Bačka from Kostajnica near the border of Bosnia[2] where he led a company of three hundred men and fought against Ottomans for thirty two years. Since Ottomans wanted to punish him after they signed a peace treaty with Austrians, Mileta moved to Bačka and changed his last name to Miletić. Mileta's son Sima, who was educated as merchant in Novi Sad, had fifteen sons and three daughters. Avram Miletić, the oldest Sima's son and grandfather of Svetozar Miletić, was merchant and songwriter who is best known for writing the earliest collection of urban lyric poetry on Serbian language.[3] The second son of Avram Miletić, also Sima like his grandfather, was a boot-maker[4] and a father of Svetozar Miletić.[5] Svetozar Miletić was the oldest of seven children born to Sima and Teodosija (née Rajić) Miletić in the village of Mošorin in Šajkaška, the Serbian Military Frontier, on 22 February 1826. His son-in-law Jaša Tomić, who was a publicist and leader of the Serbian radicals in Vojvodina, took up Miletić's mantle at the turn of the century.

Education

Miletić attended Gymnasia in Novi Sad, Modra, and Požun (Bratislava), and defended a juristical doctorate in Vienna in 1854, but found his real vocation in politics, and at once constituted himself champion of the most advanced opinions. He wrote a song Već se srbska zastava vije svuda javno (Already the Serb flag is unfurled everywhere), which was sung as the anthem of Vojvodina.

He was a political fighter for the freedom and rights of Serbs and other peoples in Austria-Hungary. Miletić was a founder of Ujedinjena omladina srpska (United Serb Youth), and founder and leader of the Srpska narodna slobodoumna stranka (Serb National Freethinkers Party). Also, he was founder and editor of the magazine Zastava (Flag; started in 1866). He took upon himself the heavy task of reconciling the traditional hostility between Serb and Magyar. Miletić had come to the conclusion that the Serbian movement in the Vojvodina could be brought into line with the general Serbian aims of liberty and unity, and also with the wider European movement associated with such names as Niccolo Tommaseo, Daniele Manin, Mazzini, Garibaldi, Léon Gambetta and Castelar. To this idea he devoted all his intellectual gifts and highly combative energies. Other Serbs also became politically engaged, sympathizing with the ideas of the United Serb Youth, a movement which attracted a number of influential figures in Serbian public life in the period of the 1860s and 1870s. (These include Svetozar Marković, Milovan Janković, Jevrem Grujić, Jovan Ilić, Čedomilj Mijatović, Jovan Đorđević, Stojan Novaković, Vaso Pelagić, Jovan Grčić Milenko, Jaša Tomić Jakov Ignjatović, Vladimir Jovanović, Milorad Popović Šapčanin, Draga Dejanović and others). Also, as a member of the Srpska Čitaonica (the Serbian Reading Room), Miletić along with a group of close associates (Jovan Đorđević, Jovan Jovanović Zmaj, Stevan Branovački and nine actors) founded the Serbian National Theatre in Novi Sad in 1861.

In the year 1844, while at the Evangelical Lycee in Pozun (Bratislava), he made the acquaintance of the Slovak leader, Ľudovít Štúr, and fell under his influence. Miletić begins to regard the Serbian people as a nation and refused Jan Kollar's concept, of only four Slavic tribes—Russian, Polish, Czech and Southern Slav—and cited Vuk Stefanović Karadžić's latest reforms based on the dialect from Eastern Herzegovina and phonetic spelling as well as Serb sovereignty before and after the Turkish invasions. On the occasion of the first great conflict in Europe Miletić saw that his people must liberate themselves from foreign yoke, if they are to survive as a nation.

Revolutions of 1848

In 1848–1849, when revolutions and rebellions were in the air, the Hungarians began their war against Austria, the Serbs in turn rose against the Hungarians for their national and civil liberties, but on the conclusion of peace they were incorporated as part of the Habsburg without any of their rights recognized, just like the rest of the nationalities.

Pre-eminent among the Serbs at the time was Svetozar Miletić, who during his student days in Pozun (Pressburg/Bratislava) edited a small newspaper entitled Serbski Soko, and then at Pest, in 1847, an almanach called Slavjanka, containing a collection of verses by upcoming Serbian poets. In 1848 Miletić was preparing a prose edition of Slavjanka, which was to include essays on the French revolution and on Kościuszko. He visited Belgrade and made friends with the foremost Liberals of Serbia. On this occasion he prepared a mission statement for a newly created student movement called simply United Youth (Ujedinjena Omladina), which was to have branches at Belgrade, Pest, Bratislava and Temesvár.

May Assembly

The proclamation in which Miletić invited all students to prepare the nation for its liberation, fell into the hands of Metternich's police, and from 1847 Miletić was under their constant observation. In April 1848, the Hofkriegsrat in Vienna decided that this youth of twenty must be rendered innocuous. For Miletić, when he saw the servility of the Serb delegation to the Diet at Bratislava, urged the younger generation to go among the people and rouse it to a struggle for national guarantees. He left Bratislava, went to Novi Sad, and then to the Military Frontiers, where he incited the Šajkaši not to go to Italy and fight against Young Italy, and not go aboard ships which were to carry them as cattle to the slaughter-house, but he pleaded with them to await the National Assembly which was to convene on the 1st to 3 May 1848 (better known as the May Assembly). This assembly was formed by the young men round Miletić, but its directive was controlled by stronger forces than they—Patriarch Josif Rajačić, Vojvoda Stevan Šupljikac, the Austrophil Serbian Government in Belgrade, and Austrian General Ban Josip Jelačić. This, and the chauvinism of the Magyars, gave to the Serbian movement in 1848, and still more in 1849, a tendency which Miletić could not agree with. He would always take time to point out that Serbs and the Slavs would not shake off their yoke through these struggles. His private inclination was to take advantage of all the disorder in Europe and go our own way—to complete national liberation. Miletić would have much preferred to find a modus vivendi with the Magyars, and that the Frontiersmen (Grenzer) should have been sent, in conjunction with Alexander Karađorđević, Prince of Serbia and Petar II Petrović Njegoš of Montenegro, to liberate Bosnia, Herzegovina and Old Serbia instead. But he was alone in these aspirations (except for Petar II Petrović-Njegoš who espoused the same ideas as Miletić), unfortunately isolated and powerless, and torn between the desire to help the Serbian cause such as it was and the awareness that it was not what it ought to be. When this proved impossible, Miletić took an increasingly lukeworm attitude in the movement from then on, and in April 1849, when the breath of reaction could already be felt, he withdrew himself altogether. Disgusted at the turn of events and the direction the national life was taking, Miletić dropped politics altogether and began to think about his interrupted schooling. He studied law in Vienna, and was granted one of the bursaries founded by Prince Mihailo (Obrenović); but he reserved to himself full liberty of political opinions and action, and for the Prince's foundation he rendered thanks to the nation!

A long period was to elapse before he could repay by his national work the debt which he owed to Rajačić (who sponsored him) and Prince Mihailo, for the reactionary Bach rėgime made all public life impossible. Miletić speedily and successfully completed his bar examination, and set up practice at Novi Sad, and about that time married. Miletić soon became famous and acquired an independent material position. It was as though he delighted in the sense of his growing powers, and yet declined to undertake any public work, so long as such conditions prevailed as permitted him from putting forth his full effort.

Political career

These conditions changed after the Austrian defeats at Solferino and Magenta, when Franz Joseph, by the October Diploma of 1860, found it necessary to promise the introduction of constitutional government. As one means of appeasing the Magyars, Franz Joseph ordered the speedy reincorporation of the Serbian Vojvodina in the Kingdom of Hungary. But they were not satisfied with this concession, and insisted upon the constitution of 1848, which was only granted after Austria's fresh defeat at Königgrätz in 1866. In the six years during which this trial of strength between Austria and Hungary lasted the attitude of the Serbs and Croats, Romanians and Slovaks, assumed very considerable importance. Indeed if the nationalities had sided with Austria during this period, as they had done in 1848, Hungary would hardly have attained that complete independence from the Austrian monarchy which was embodied in the Compromise, or Ausgleich of 1867. But the absolutist régime of Alexander von Bach had alienated the nationalities, and they flung themselves into the arms of Magyar Liberalism. The Magyars for their part at this time laid greater streets on the Liberal than upon the Magyar side of things.

And no one did more for this new policy than Svetozar Miletić, as representative of the Hungarian Serbs. He took the role of mediator graciously and the burden of reconciling the traditional animosities between two stubborn nationalities, and dissipating the doubts and suspicions which ten years of reaction had kindled. Miletić had reached the conviction that the Serbian movement in the Vojvodina could be brought into line with the general Serbian aims of liberty and unity, and also with the wider European movement. To this idea he devoted all his intellectual gifts and highly combative temperament.

For a certain time circumstances favoured him. Mihailo Obrenović III, Prince of Serbia was in touch with Andrassy and Ferenc Deak, who were at the time willing to help Serbia acquire Bosnia and Herzegovina and liberate her kinsmen under the Turkish yoke; and for this Miletić was ready and eager to render them any possible service in return. The Vojvodina was reincorporated towards the end of 1860, and on 4 January 1861, Miletić published an article which was long to serve as his party's policy, and in which, while not taking exception to Hungary's acceptance of the Vojvodina at the hands of Austria, he announced to the latter that she need no longer reckon upon the Serbs in her quarrels with other nations. In the same year, at a political meeting of Hungarian Serbs, held at Sremski Karlovci in Syrmia, he put forward the idea of seeking guarantees for their nationality, by friendly agreement with the Magyars. In the year 1865 he was elected to the Croatian Sabor and supported a peculiar kind of Dualism under which both Austria and Hungary would be reorganized on a federal basis: he therefore joined the party club which passed as Magyarophil.

Among the older Serbian intellectuals this policy awakened but little response. But for the very reason the younger generation—intelligentsia, merchants, and artisans alike—gathered all the more eagerly around "the eagle of Novi Sad," where in 1866 they organized the "United Youth" (Ujedinjena Omladina) as the symbol of political unity. The foremost Serbian poets and writers of that time gave their support to the Omladina movement, which found alike its Achilles Miletić and its Ajax in Laza Kostić, Odysseus in Đura Jakšić, and Homer in Jovan Jovanović Zmaj. This new bourgeoisie was in close contact with the peasantry, and little by little, between 1861 and 1871, the whole Serbian nation in the Vojvodina gave its adherence to the national party of Miletić. When in 1872 elections were held for the autonomous Church Assembly, this party obtained 72 out of a total of 75 seats. Throughout this period all the honours which it was in the power of the Serbs to confer were lavished upon Svetozar Miletić as their recognized leader. From 1865 to 1884 he represented them in the Parliament at Budapest; in 1861 and 1867 he was Mayor of Novi Sad; in 1871 he became President of the Matica Srpska, the oldest Serbian cultural institution. And the Omladina in its dreams accorded him the honour of Voivode in the Banat and Bačka and Supreme Zupan in the three counties which Deak, in 1862, had promised to delimit on a national basis.

The Compromise

Naturally when the Magyars concluded their 1867 Compromise with Austria and the foreign policy of the new Dual Monarchy fell into the hands of Count Andrassy, whom Austria had hanged in effigy in 1849; when Prince Mihailo of Serbia was assassinated in 1868 and Andrassy adopted as part of his programme the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina; and when the New Hungary began to falsify their former Liberal principles in the interest of wholesale Magyarisation, then no one reacted more strongly to the changed situation than he who had up till this time been the firmest believer in Magyar liberalism. Politically, the principle underlying the agreement was that the empire should be divided into two portions, in one of these the Magyars were to rule, in the other the Germans; in either section the Slav races (the Serbs and Croatians, the Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, Ruthenians, and Slovenes) and the Romanians and Italians were to be placed in a position of political inferiority, according to Henry de Worms's The Austro-Hungarian Empire (London, 1876). Thus Miletić became the champion against whose breast were pointed all the lances of authority in Hungary and in Austria. With their policy of "whip and hay," of repression and secret funds, Andrassy, Lonyay and Kalman Tisza tried to split up the party of Miletić after Prince Mihailo's murder. Andrassy even accused Miletić of complicity in the crime and suspended him from his post as Mayor of Novi Sad. This manoeuvre failed, and the ranks of the National Party closed firmly than ever around their leader. In the same way in 1870 Andrassy secured Miletić's sentence of a year's imprisonment owing to his attacks upon the corrupt anti-national regime of Baron Levin Rauch in Croatia. Both on entering and leaving prison Miletic had a triumphal reception from his compatriots in the Voyvodina, and henceforth he was uncontested master of their souls. But even in this situation he was at all times ready to come to terms with the Magyars. His conditions of peace were summed up in a single phrase: "The Balkans for the Balkan people." Roman Catholic Austria, he argued, could not satisfy her own Catholic Slavs—the Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes and Croats—let alone hope to fulfill a mission in the Balkans.

Serbian-American inventor Mihajlo Pupin in his highly acclaimed, Pulitzer prize-winning autobiography From Immigrant to Inventor, wrote on page 21:

Svetozar Miletich, the great nationalistic leader of the Serbs in Austria-Hungary, visited Panchevo, and the people prepared a torchlight procession for him. This procession was to be a protest of Panchevo and the whole of Banat against the emperor's treachery of 1869. My father had protested long before by excluding the emperor's picture from our house. That visit of Miletich marks the beginning of a new political era in Banat, the era of nationalism. The schoolboys of Panchevo turned out in great numbers, and I was one of them, proud to become one of the torch-bearers.

Incarceration

Consequently Miletić fostered such opposition to Austria's progress in the Balkans, that the occupation of Bosnia logically involved the political extinction of Miletić. In accordance with the wishes of Franz Joseph I of Austria and Count Andrassy, Kálmán Tisza, with his accustomed brutality, and in entire disregard of parliamentary immunity, ordered the arrest of Miletić on 5 July 1876, and then began his search for incriminating evidence. In the prisons of Voyvodina he found a single witness, a decayed individual whose word no court free from political influence would have dreamt of accepting. Not knowing how long the Eastern Crisis ushered in by Serbo-Turkish War would last, Tisza postponed the trial for eighteen months. Setting his hopes on European opinion, Mihailo Polit-Desančić, Miletić's comrade-in-arms, did all he could to hasten an investigation (which would ultimately prove Miletić's innocence) by brilliantly defending him in court in Budapest, but to no avail. At the beginning of 1878 Miletić was condemned for high treason and sentenced to five years' ordinary imprisonment and a heavy fine. On 27 November 1879, when the occupation of Bosnia was already an accomplished fact, Franz Joseph pardoned the victim of his policy of Balkan expansion. Though Miletić's health was broken by his three and a half years of confinement, he still found the strength to lead his compatriots in the Voyvodina for another two years. In 1881, in face of acute pressure on the part of the administrative authorities, he secured his election to the Parliament of Budapest, and in a speech of the following year summoned the Monarchy to evacuate Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The words of Hamlet, which perhaps were more often on his lips than those of any character in literature, became an obsession with him. Hic et ubique—at every turn, on floor and roof!—he saw Kálmán Tisza lurking about, pulling down the wall of his room upon him or laying weights upon his head and making it impossible for him to sleep. From 1884 to 1889, his illness was so severe that he had to be removed to an asylum. Then at last his madness left him, but, unhappy, though he lived till the year 1901, his mind never fully recovered sufficiently enough for him to resume his leadership of the Serbs of Voyvodina, now badly disunited and weakened. His disappearance from public life contributed very materially to the long period of depression through which the Serbs went, and which lasted right on till the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. And even today the Serbs of Voyvodina are all too conscious of the vacuum that Miletić left. He possessed to a surprising degree the arts of the orator, combined with a magnificent and striking physical presence which today is embodied in his monument in Novi Sad where he was the Lord Mayor.

Miletić died at Vršac on 4 February 1901, and was buried in Novi Sad.

Works

- Na Tucindan (1860; Before Christmas)

- Istočno pitanje (1863; The Eastern Question)

- Značaj i zadatak srpske omladine (1866, The importance and the task of the Serbian Youth movement)

- Federalni dualizam (1866; Federal dualism)

- Osnova programa za srpsku liberalno-opozicionu stranu (1869; The basic program of the Serbian liberal-opposition party)

- O obrazovanju ženskinja (1871; On the education of women)

Legacy

There are several villages named after him: Svetozar Miletić, a village in the Sombor municipality; Miletićevo, a village in the Plandište municipality.[citation needed] Although there is a village called Srpski Miletić in the Odžaci municipality, it's not related to the Svetozar Miletić, since this village had name "Miletić" before Svetozar Miletić was born. The village was probably named after some other person with surname "Miletić".[citation needed]

He is included in The 100 most prominent Serbs.

See also

References

- ^ "Political, cultural, artistic activities of the Ujedinjena Omladina Sppska as a case of networking" (PDF).

- ^ Popović, Bogdan; Jovan Skerlić (1934). Srpski književni glasnik, Volume 42. p. 283.

Милетићев отац је, године 1876, казивао Александру Сандићу да је његов прадед, Милета Завишић, дошао у Бачку са босанске границе, из Костајнице, што много не противречи Милетићеву казивању...

- ^ Petrović, Nikola (1958), Svetozar Miletić, 1826–1901 (in Serbian), Belgrade: Nolit, p. 8, OCLC 7888773,

дични предак Милета Завишић, гласовити јунак, тридесет и две године, са својом четом од триста јунака вршио упаде на турску територију и кажњавао Турке за њихова недела према Србима. Када су се Аустријанци и Турци измирили, Турци затраже Милетину главу. Да би се склонио од неминовне погибије, Милета се пресели са својом породицом у Бачку и прозове се Милетић, да би заметнуо траг. Милетин син Сима, према предању Светозарев прадед, изучи трговачки занат у Новом Саду и ту се ожени и изроди петнаест синова и три кћери. ... Симин најстарији син Аврам, Светозарев дед, рођен је 1755...

- ^ Popović, Bogdan; Jovan Skerlić (1934). Srpski književni glasnik, Volume 42. p. 283.

Син Аврама Милетића, Сима чизмар...

- ^ Зборник Матице српске за друштвене науке, Volumes 19–21 (in Serbian). Novi Sad: Matica Srpska. 1958. p. 104.

Аврам Милетић, деда Светозара Милетића...

Bibliography

- Jovan Mirosavljević, Brevijar ulica Novog Sada 1745–2001, Novi Sad, 2002.

- Vasa Stajić, "Svetozar Miletic" in The Slavonic Review, 1928, p. 106–113.