Syncopation

In music, syncopation involves a variety of rhythms which are in some way unexpected which make part or all of a tune or piece of music off-beat. More simply, syncopation is a general term for "a disturbance or interruption of the regular flow of rhythm": a "placement of rhythmic stresses or accents where they wouldn't normally occur."[1] The correlation of at least two sets of time intervals.[2]

Syncopation is used in many musical styles, and is fundamental in styles such as ragtime, jazz, jump blues, funk, gospel, reggae, dub, hip hop, breakbeat, UK garage, dubstep, drum'n'bass, progressive house, progressive rock / metal, djent, groove metal, nu metal, samba, baião, and ska. "All dance music makes use of syncopation and it's often a vital element that helps tie the whole track together".[3] In the form of a back beat, syncopation is used in virtually all contemporary popular music.

Syncopation has been an important element of European musical composition since at least the Middle Ages. J.S. Bach and Handel used syncopated rhythms as an inherent part of their compositions; Haydn used it to create variety. Syncopation was used by Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert, especially in their symphonies, for both purposes. This can be heard in Mozart's 38th and Beethoven's 7th. Syncopation is an essential part of the character of some musical styles, such as jazz and ragtime. Hungarian Csárdás song-dances are always syncopated. The "Scotch snap" of Scotland also feature syncopation.[1][4]

Syncopation can also occur when a strong harmony is placed on a weak beat, for instance when a 7th-chord is placed on the second beat of 3

4 measure or a dominant is placed at the fourth beat of a 4

4 measure. The latter frequently occurs in tonal cadences in 18th and early 19th century music and is the usual conclusion of any section.

A hemiola can also be seen as one straight measure in 3 with one long chord and one short chord and a syncope in the measure thereafter, with one short chord and one long chord. Usually, the last chord in a hemiola is a (bi-)dominant, and as such a strong harmony on a weak beat, hence a syncope.

Types of syncopation

Technically, "syncopation occurs when a temporary displacement of the regular metrical accent occurs, causing the emphasis to shift from a strong accent to a weak accent."[5] "Syncopation is," however, "very simply, a deliberate disruption of the two- or three-beat stress pattern, most often by stressing an off-beat, or a note that is not on the beat."[6]

Suspension

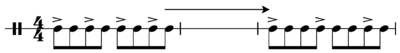

In the following example, there are two points of syncopation where the third beats are carried over (sustained) from the second beats rather than missed. In the same way, the first beat of the second bar is carried over from the fourth beat of the first bar.

Though syncopation may be highly complex, dense or complex looking rhythms often contain no syncopation. The following rhythm, though dense, stresses the regular downbeats, 1 & 4 (in 6

8):[6]

However, whether it's a placed rest or an accented note, any point in a piece of music that moves your perspective of the downbeat is a point of syncopation because it's shifting where the strong and weak accents are built."[6]

"Even-note" syncopation

For example, in meters with even numbers of beats (2

4, 4

4, etc.), the stress normally falls on the odd-numbered beats. If the even-numbered beats are stressed instead, the rhythm is syncopated. Accordingly, the former implies duple meter (1212) while the latter implies quadruple meter (1234).

Off-beat syncopation

The stress can shift by less than a whole beat so it falls on an off beat, as in the following example where the stress in the first bar is shifted back by an eighth note (or quaver) :

Whereas the notes are expected to fall on the beat :

Playing a note ever so slightly before, or after, a beat is another form of syncopation because this produces an unexpected accent :

It can be helpful to think of a 4

4 rhythm in eighth notes and count it as "1-and-2-and-3-and-4-and". In general emphasizing the "and" would be considered the off-beat.

Anticipated bass

Anticipated bass[7] is a bass tone that comes syncopated shortly before the downbeat, which is used in Son montuno Cuban dance music. Timing can vary, but it usually falls on the 2+ as well as the 4 of the 4

4 time, thus anticipating the third and first beats. This pattern is commonly known as the Afro-Cuban bass tumbao.

Physical effects

Missed beat syncopation causes a physical effect in the body of the listener as his/her body moves to supply the missing beat. Complex syncopation has been used to overload the brain to induce abreaction and as a prelude to brain washing.[8][9][10] Cognitively, Temperley[11] argues that most accurately syncopation can be described as involving "displacement; in a syncopation, an accent that belongs on a particular strong beat is shifted or displaced to a weak one."

Transformation

Richard Middleton[12] suggests adding the concept of transformation to Narmour's[13] prosodic rules which create rhythmic successions in order to explain or generate syncopations. "The syncopated pattern is heard 'with reference to', 'in light of', as a remapping of, its partner." He gives examples of various types of syncopation: Latin, backbeat, and before-the-beat. First however, one may listen to the audio example of stress on the "strong" beats, where expected:

Latin equivalent of simple 4

4

This unsyncopated rhythm is shown in the first measure directly below:

The third measure depicts the syncopated rhythm in the following audio example in which the first and fourth beat are provided as expected, but the accent unexpectedly lands in between the second and third beats, creating a familiar "Latin rhythm" known as tresillo:

Backbeat transformation of simple 4

4

The accent may be shifted from the first to the second beat in duple meter (and the third to fourth in quadruple), creating the backbeat rhythm familiar in rock drumming beatbox stereotypes:

Different crowds will "clap along" at concerts on either 1 & 3 or 2 & 4, as above.

"Satisfaction" example

The phrasing of "Satisfaction", a good example of syncopation,[6] is derived here from its theoretic unsyncopated form, a repeated trochee (¯ ˘ ¯ ˘). A backbeat transformation is applied to "I" and "can't", and then a before-the-beat transformation is applied to "can't" and "no".[12]

1 & 2 & 3 & 4 & 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 &

Repeated trochee: ¯ ˘ ¯ ˘

I can't get no - o

Backbeat trans.: ¯ ˘ ¯ ˘

I can't get no - o

Before-the-beat: ¯ ˘ ¯ ˘

I can't get no - o

This demonstrates how each syncopated pattern may be heard as a remapping, "'with reference to'," or, "'in light of'," an unsyncopated pattern.[12]

See also

- Anacrusis

- Counting (music)

- Syncopation (dance)

- Syncope and epenthesis, analogous linguistic concepts where vocal rhythm causes the loss or addition of sounds to a word

References

- ^ a b

Hoffman, Miles (1997). "Syncopation". National Symphony Orchestra. NPR. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Patterson, William Morrison, 'Rhythm of Prose'( Introductory Outline), Columbia University Press 1917

- ^ Snoman, Rick (2004). Dance Music Manual: Toys, Tools, and Techniques, p.44. ISBN 0-240-51915-9.

- ^ Jazz in print (1856-1929): an anthology of selected early readings in jazz ... By Karl Koenig. reprint from Nov 1901. Musician. Pendragon Press. page 67

- ^ Reed, Ted (1997). Progressive Steps to Syncopation for the Modern Drummer, p.33. ISBN 0-88284-795-3.

- ^ a b c d Day, Holly and Pilhofer, Michael (2007). Music Theory For Dummies, p.58-60. ISBN 0-7645-7838-3.

- ^ Peter Manuel (1985). "The anticipated bass in Cuban popular music," Latin American Music Review, Vol. 6, No. 2, Autumn-Winter, pp. 249-261.

- ^ William Sargent, Battle for the Mind, p. 100, Doubleday 1957, reprinted by Malor Books, 1997

- ^ P.Verger, Dieux d'Afrique, Paul Hartmann (open publisher), Paris, 1954

- ^ Maya Deren, Divine Horsemen The Living Gods of Haiti, Thames and Hudson, London, 1953

- ^ Temperley, David (1999). "Syncopation in Rock: A Perceptual Perspective". Source: Popular Music, Vol. 18, No. 1, (Jan., 1999), pp. 19-40. Published by: Cambridge University Press. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/853567. Accessed: 26 May 2008 17:33

- ^ a b c Middleton (1990/2002). Studying Popular Music, p.212-13. Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 0-335-15275-9.

- ^ Narmour (1980). p.147-53. Cited in Middleton (1990/2002), p.212-13.

Sources

- Seyer, Philip, Allan B. Novick and Paul Harmon (1997). What Makes Music Work. Forest Hill Music. ISBN 0-9651344-0-7.

External links