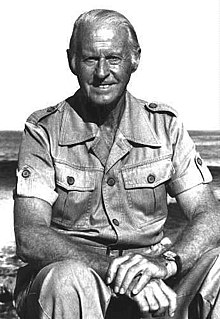

Thor Heyerdahl

Thor Heyerdahl | |

|---|---|

Thor Heyerdahl | |

| Born | October 6, 1914 |

| Died | April 18, 2002 |

| Nationality | Norwegian |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | ethnographer adventurer |

Thor Heyerdahl (October 6, 1914 Larvik, Norway – April 18, 2002 Colla Micheri, Italy) was a Norwegian ethnographer and adventurer with a scientific background in zoology and geography. Heyerdahl became famous for his Kon-Tiki expedition, in which he sailed 4,300 miles (8,000 km) by raft from South America to the Tuamotu Islands.

Early years

As a young child, Thor Heyerdahl established a strong interest in zoology. He created a small museum in his childhood home, with a Vipera berus as the main attraction. He studied Zoology and Geography at Oslo University. At the same time he studied privately Polynesian culture and history, consulting the then world's largest private collection of books and papers on Polynesia, owned by Bjarne Kroepelin, a wealthy wine merchant in Oslo. This collection was later purchased by the Oslo University Library from Kroepelin's heirs and was attached to the Kon-Tiki Museum research department. After seven terms and consultations with experts in Berlin, a project was developed and sponsored by his zoology professors, Kristine Bonnevie and Hjalmar Broch. He was to visit some isolated Pacific island group and study how the local animals had found their way there. Right before sailing together to the Marquesas Islands he married his first wife, Liv, whom he had met shortly before enrolling at the university, and who had studied economics there.

Fatu Hiva

Penguin edition, 1976

The original b/w photo is printed in the book with the caption "Feeling like a king, I could actually put an ancient Marquesan royal crown on my head for the occasion. Or was I the first hippy?"

The events surrounding his stay on the Marquesas, most of the time on Fatu Hiva, were told first in his book Paa Jakt efter Paradiset ['Hunt for Paradise'] (1938). This was published in Norway, and because of the outbreak of World War II was never translated and rather forgotten. Many years later, after having achieved fame with other adventures and books on other subjects, Heyerdahl published a new account of this voyage under the title Fatu Hiva (George Allen & Unwin, 1974). The young couple left Norway in 1936 and stayed about a year in the South Seas.

The Kon-Tiki Expedition

In the Kon-Tiki Expedition, Heyerdahl and five fellow adventurers went to Peru, where they constructed a pae-pae raft from balsa wood and other native materials, a raft that they called the Kon-Tiki. The Kon-Tiki expedition was inspired by old reports and drawings made by the Spanish Conquistadors of Inca rafts, and by native legends and archaeological evidence suggesting contact between South America and Polynesia. After a 101 day, 4,300 mile (8,000 km) journey across the Pacific Ocean, Kon-Tiki smashed into the reef at Raroia in the Tuamotu Islands on August 7, 1947.

Kon-Tiki demonstrated that it was possible for a primitive raft to sail the Pacific with relative ease and safety, especially to the west (with the wind). The raft proved to be highly maneuverable, and fish congregated between the two balsa logs in such numbers that ancient sailors could have possibly relied on fish for hydration in the absence of other sources of fresh water. Inspired by Kon-Tiki, other rafts have repeated the voyage. Heyerdahl's book about the expedition, Kon-Tiki, has been translated into over 50 languages. The documentary film of the expedition, itself entitled Kon-Tiki, won an Academy Award in 1951.

Anthropologists continue to believe, based on linguistic, physical and genetic evidence, that Polynesia was settled from west to east, migration having begun from the Asian mainland. There are controversial indications, though, of some sort of South American/Polynesian contact, most notably in the fact that the South American sweet potato served as a dietary staple throughout much of Polynesia. Heyerdahl attempted to counter the linguistic argument with the analogy that, guessing the origin of African-Americans he would prefer to believe that they came from Africa, judging from their skin colour, and not from England, judging from their speech.

Heyerdahl's theory of Polynesian origins

It has been suggested that Kon-Tiki#Anthropology be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since December 2007. |

Heyerdahl claimed that in Incan legend there was a sun-god named Con-Tici Viracocha who was the supreme head of the mythical fair-skinned people in Peru. The original name for Virakocha was Kon-Tiki or Illa-Tiki, which means Sun-Tiki or Fire-Tiki. Kon-Tiki was high priest and sun-king of these legendary "white men" who left enormous ruins on the shores of Lake Titicaca. The legend continues with the mysterious bearded white men being attacked by a chief named Cari who came from the Coquimbo Valley. They had a battle on an island in Lake Titicaca, and the fair race was massacred. However, Kon-Tiki and his closest companions managed to escape and later arrived on the Pacific coast. The legend ends with Kon-Tiki and his companions disappearing westward out to sea.

When the Spaniards came to Peru, Heyerdahl asserted, the Incas told them that the colossal monuments that stood deserted about the landscape were erected by a race of white gods who had lived there before the Incas themselves became rulers. The Incas described these "white gods" as wise, peaceful instructors who had originally come from the north in the "morning of time" and taught the Incas' primitive forefathers architecture as well as manners and customs. They were unlike other Native Americans in that they had "white skins and long beards" and were taller than the Incas. The Incas said that the "white gods" had then left as suddenly as they had come and fled westward across the Pacific. After they had left, the Incas themselves took over power in the country.

Heyerdahl said that when the Europeans first came to the Pacific islands, they were astonished that they found some of the natives to have relatively light skins and beards. There were whole families that had pale skin, hair varying in color from reddish to blonde, and almost Semitic, hook-nosed faces. In contrast, most of the Polynesians had golden-brown skin, raven-black hair, and rather flat noses. Heyerdahl claimed that when Jakob Roggeveen first discovered Easter Island in 1722, he supposedly noticed that many of the natives were white-skinned. Heyerdahl claimed that these people could count their ancestors who were "white-skinned" right back to the time of Tiki and Hotu Matua, when they first came sailing across the sea "from a mountainous land in the east which was scorched by the sun." The ethnographic evidence for these claims is outlined in Heyerdahl's book Aku Aku: The Secret of Easter Island.

Heyerdahl proposed that Tiki's neolithic people colonized the then-uninhabited Polynesian islands as far north as Hawaii, as far south as New Zealand, as far east as Easter Island, and as far west as Samoa and Tonga around A.D. 500. They supposedly sailed from Peru to the Polynesian islands on pae-paes--large rafts built from balsa logs, complete with sails and each with a small cottage. They built enormous stone statues carved in the image of human beings on Pitcairn, the Marquesas, and Easter Island that resembled those in Peru. They also built huge pyramids on Tahiti and Samoa with steps like those in Peru. But all over Polynesia, Heyerdahl found indications that Tiki's peaceable race had not been able to hold the islands alone for long. He found evidence that suggested that seagoing war canoes as large as Viking ships and lashed together two and two had brought Stone Age Northwest American Indians to Polynesia around A.D. 1100, and they mingled with Tiki's people. The oral history of the people of Easter Island, at least as it was documented by Heyerdahl, is completely consistent with this theory, as is the archaeological record he examined (Heyerdahl 1958). In particular, Heyerdahl obtained a radiocarbon date of A.D. 400 for a charcoal fire located in the pit that was held by the people of Easter Island to have been used as an "oven" by the "Long Ears," which Heyerdahl's Rapa Nui sources, reciting oral tradition, identified as a white race which had ruled the island in the past (Heyerdahl 1958). Genetic research has found that modern-day Polynesians are more closely related to Southeast Asians than to American Indians. Easter Islanders are of Polynesian descent.

Expedition to Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

In 1955-1956, Heyerdahl organized the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Rapa Nui (Easter Island). The expedition's scientific staff included Arne Skjølsvold, Carlyle Smith, Edwin Ferdon and William Mulloy. Heyerdahl and the professional archaeologists who traveled with him spent several months on Rapa Nui investigating several important archaeological sites. Highlights of the project include experiments in the carving, transport and erection of the famous moai, as well as excavations at such prominent sites as Orongo and Poike. The expedition published two large volumes of scientific reports (Reports of the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the East Pacific) and Heyerdahl later added a third (The Art of Easter Island). The work of this expedition laid the foundation for much of the archaeological research that continues to be conducted on the island. Heyerdahl's popular book on the subject, Aku-Aku was another international best-seller.

In "Easter Island: the Mystery Solved" (Random House, 1989), Heyerdahl offered a more detailed theory of the island's history. Based on native testimony and archeological research, he claimed the island was originally colonized by Hanau eepe ("Long Ears"), from South America, and that Polynesians Hanua momoko ("Short Ears") arrived only in the mid-16th century; they may have come independently or perhaps were imported as workers. According to Heyerdahl, something happened between Admiral Roggeveen's discovery of the island in 1722 and James Cook's visit in 1774; while Roggeveen encountered white, Indian, and Polynesian people living in relative harmony and prosperity, Cook encountered a much smaller population consisting mainly of Polynesians and living in privation.

Heyerdahl speculates there was an uprising of "Short Ears" against the ruling "Long Ears." The "Long Ears" dug a defensive moat on the eastern end of the island and filled it with kindling. During the uprising, Heyerdahl claimed, the "Long Ears" ignited their moat and retreated behind it, but the "Short Ears" found a way around it, came up from behind, and pushed all but two of the "Long Ears" into the fire.

The Boats Ra and Ra II

In 1969 and 1970, Heyerdahl built two boats from papyrus and attempted to cross the Atlantic from Morocco in Africa. Based on drawings and models from ancient Egypt, the first boat, named Ra, was constructed by boat builders from Lake Chad in the Republic of Chad using reed obtained from Lake Tana in Ethiopia and launched into the Atlantic Ocean from the coast of Morocco. After a number of weeks, Ra took on water after its crew made modifications to the vessel that caused it to sag and break apart. The ship was abandoned and the following year, another similar vessel, Ra II was built by boatmen from Lake Titicaca in Bolivia and likewise set sail across the Atlantic from Morocco, this time with great success. The boat reached Barbados, thus demonstrating that mariners could have made trans-Atlantic voyages by sailing with the Canary Current.[1] While the purpose of the Ra voyages was merely to prove the seaworthiness of ancient vessels constructed of buoyant reeds, others contentiously have cited the success of the Ra II expedition as evidence that Egyptian mariners could have journeyed, by design or happenstance, to the New World in prehistoric times.[citation needed]

A book, The Ra Expeditions, and a film documentary were made about the voyages.

Apart from the primary aspects of the expedition, Heyerdahl deliberately selected a crew representing a great diversity in race, nationality, religion and political viewpoint in order to demonstrate that at least on their own little floating island, people could cooperate and live peacefully. Additionally, the expedition took samples of ocean pollution and presented their report to the United Nations.

The Tigris

Heyerdahl built yet another reed boat, Tigris, which was intended to demonstrate that trade and migration could have linked Mesopotamia with the Indus Valley Civilization in what is now modern-day Pakistan. Tigris was built in Iraq and sailed with its international crew through the Persian Gulf to Pakistan and made its way into the Red Sea. After about 5 months at sea and still remaining seaworthy, the Tigris was deliberately burnt in Djibouti, on April 3 1978 as a protest against the wars raging on every side in the Red Sea and Horn of Africa. In Heyerdahl's open letter [1] to the Secretary of the United Nations he said in part:

- ' Today we burn our proud ship... to protest against inhuman elements in the world of 1978... Now we are forced to stop at the entrance to the Red Sea. Surrounded by military airplanes and warships from the world's most civilized and developed nations, we have been denied permission by friendly governments, for reasons of security, to land anywhere, but in the tiny, and still neutral, Republic of Djibouti. Elsewhere around us, brothers and neighbors are engaged in homicide with means made available to them by those who lead humanity on our joint road into the third millennium.

- 'To the innocent masses in all industrialized countries, we direct our appeal. We must wake up to the insane reality of our time.... We are all irresponsible, unless we demand from the responsible decision makers that modern armaments must no longer be made available to people whose former battle axes and swords our ancestors condemned.

- 'Our planet is bigger than the reed bundles that have carried us across the seas, and yet small enough to run the same risks unless those of us still alive open our eyes and minds to the desperate need of intelligent collaboration to save ourselves and our common civilization from what we are about to convert into a sinking ship.'

In the years that followed, Heyerdahl was often outspoken on issues of international peace and the environment. The Tigris was crewed by eleven men: Thor Heyerdahl (Norway), Norman Baker (USA), Carlo Mauri (Italy), Yuri Senkevich (USSR), Germán Carrasco (Mexico), Hans Petter Bohn (Norway), Rashad Nazir Salim (Iraq), Norris Brock (USA), Toru Suzuki (Japan), Detlef Zoltzek (Germany), Asbjørn Damhus (Denmark).

Other work

Thor Heyerdahl also investigated the mounds found on the Maldive Islands in the Indian Ocean. There, he found sun-oriented foundations and courtyards, as well as statues with elongated earlobes. Both of these archeological finds fit with his theory of a sea-faring civilization which originated in what is now Sri Lanka, colonized the Maldives, and influenced or founded the cultures of ancient South America and Easter Island. His discoveries are detailed in his book, "The Maldive Mystery."

In 1991 he studied the Pyramids of Güímar on Tenerife and declared that they cannot be random stone heaps, but actual pyramids. He also discovered their special astronomical orientation. Heyerdahl advanced a theory according to which the Canaries had been bases of ancient shipping between America and the Mediterranean.

His last project was presented in the book Jakten på Odin, ('the search for Odin'), in which he initiated excavations in Azov, near the Sea of Azov at the northeast of the Black Sea. He searched for the possible remains of a civilization to match the account of Snorri Sturluson in Ynglinga saga, where Snorri describes how a chief called Odin led a tribe, called the Æsir in a migration northwards through Saxland, to Fyn in Denmark settling in Sweden. There, according to Snorri, he so impressed the natives with his diverse skills that they started worshipping him as a god after his death (see also House of Ynglings and Mythological kings of Sweden). Heyerdahl accepted Snorri's story as literal truth. This project generated harsh criticism and accusations of pseudo-science from historians, archaeologists and linguists in Norway, who accused Heyerdahl of selective use of sources, and a basic lack of scientific methodology in his work.

The central claims in this book are based on similarities of names in Norse mythology and geographic names in the Black Sea-region, e.g. Azov and æsir, Udi and Odin, Tyr and Turkey. Philologists and historians reject these parallels as mere coincidences, and also anachronisms, for instance the city of Azov did not have that name until over 1000 years after Heyerdahl claims the æsir dwellt there. The controversy surrounding the search for Odin-project was in many ways typical of the relationship between Heyerdahl and the academic community. His theories rarely won any scientific acceptance, whereas Heyerdahl himself rejected all scientific criticism and concentrated on publishing his theories in best-selling books to the larger masses.

Heyerdahl claimed that the Udi ethnic minority in Azerbaijan was the descendants of the ancestors of the Scandinavians. He travelled to Azerbaijan on a number of occasions in the final two decades of his life and visited the Kish church. Heyerdahl's Odin theory was rejected by all serious historians, archaeologists, and linguists.

Heyerdahl was also an active figure in Green politics. He was the recipient of numerous medals and awards. He also received 11 honorary doctorates from universities in the Americas and Europe.

Subsequent years

In subsequent years, Heyerdahl was involved with many other expeditions and archaeological projects. However, he remained best known for his boat-building, and for his emphasis on cultural diffusionism. He died, aged 87, from a brain tumor. The Norwegian government granted Heyerdahl the honor of a state funeral in the Oslo Cathedral on April 26, 2002. His cremated remains lie in garden of his family's home in Colla Micheri.[2]

Legacy

- Heyerdahl's expeditions were spectacular, and his heroic journeys in flimsy boats caught the public imagination. Although much of his work remains controversial within the scientific community, Heyerdahl undoubtedly increased public interest in ancient history and in the achievements of various cultures and peoples around the world — he also showed that long distance ocean voyages were technically possible even with ancient designs. As such, he was a major practitioner of experimental archaeology. Heyerdahl's books served to inspire several generations of readers. He introduced readers of all ages to the fields of archaeology and ethnology by making them attractive through his colorful adventures. This Norwegian adventurer often broke the bounds of conventional thinking and was unapologetic for doing so. "Boundaries?", he is quoted as asking, "I have never seen one but I hear that they exist in the minds of most people."

- In 1954 William Willis sailed alone from Peru to American Samoa on the small raft named "Seven Little Sisters".

- Kantuta Expeditions, a repeated expeditions of Kon-Tiki by Eduard Ingriš.

- Thor Heyerdahl's grandson, Olav Heyerdahl, retraced his grandfather's Kon-Tiki voyage in 2006, as part of a six-member crew. The voyage, called the Tangaroa Expedition, was intended as a tribute to Thor Heyerdahl, as well as a means to monitor the Pacific Ocean's environment. A film about the voyage is in preparation.

Decorations and honorary degrees

Heyerdahl's numerous awards and honors include the following:

- Retzius Medal, Royal Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography (1950)

- Mungo Park Medal, Royal Scottish Society for Geography (1951)

- Bonaparte-Wyse Gold Medal, Société de Géographie de Paris (1951)

- Commander of the Royal Norwegian Order of St Olav (1951) and with Star, (1970)

- Bush Kent Kane Gold Medal, Geographical Society of Philadelphia (1952)

- Honorary Member, Geographical Societies of Norway (1953), Peru (1953), Brazil (1954).

- El Orden por Meritos Distinguidos, Peru (1953)

- Elected Member Norwegian Academy of Sciences (1958)

- Fellow, New York Academy of Sciences (1960)

- Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Oslo, Norway (1961)

- Vega Gold Medal, Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography (1962)

- Lomonosov Medal, Moscow State University (1962)

- Gold Medal, Royal Geographical Society, London (1964)

- Distinguished Service Award, Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, Washington, USA (1966)

- Grande Ufficiale Ordine Al Merito della Republica Italiana (1968)

- Commander, American Knights of Malta (1970)

- Order of Merit, Egypt (1971)

- Grand Officer, Royal Alaouites Order, Morocco (1971)

- Kiril i Metodi Award, Geographical Society, Bulgaria (1972)

- Honorary Professor, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Mexico (1972)

- Officer, La Orden El Sol del Peru (1975)

- International Pahlavi Environment Prize, United Nations (1978)

- Order of the Golden Ark, Netherlands (1980)

- Doctor Honoris Causa, USSR Academy of Science (1980)

- Bradford Washburn Award, Museum of Science, Boston, USA, (1982)

- Doctor Honoris Causa, University of San Martin, Lima, Peru, (1991)

- Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Havana, Cuba (1992)

- Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Kiev, Ukraine (1993)

- President's Medal, Pacific Lutheran University, Tacoma, USA (1996)

See also

- Asteroid 2473 Heyerdahl is named after the explorer

- M/S Thor Heyerdahl, a ferry named after him (Now M/S Vana Tallinn)

- HNoMS Thor Heyerdahl, a frigate of the Norwegian Navys Fridtjof Nansen class frigates named after him

- Thor Heyerdahl, a refurbished schooner, used for youth work and owned by a former member of the Tigris expedition [2]

- List of notable brain tumor patients

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact

References

- ^ Ryne, Linn. "Voyages into History." Norway - the official site in the United States. Retrieved 01-13-08.

- ^ "Thor Heyerdahl's Final Projects." Azerbaijan International 10(2). http://www.azari.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/ai102_folder/102_articles/102_heyerdahl_storfjell.html

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Aku-Aku: The Secret of Easter Island. Rand McNally. 1958.

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Kon-Tiki, 1950 Rand McNally & Company.

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Fatu Hiva. Penguin. 1976.

- Heyerdahl, Thor. Early Man and the Ocean: A Search for the Beginnings of Navigation and Seaborne Civilizations, February 1979.

External links

- Kon-Tiki Museum

- Thor Heyerdahl Biography and Bibliography

- Thor Heyerdahl expeditions

- the 'Tigris' expedition, with Heyerdahl's war protest

- Bjornar Storfjell's account: A reference of his last project Jakten på Odin

- National Geographic biography

- Forskning.no Biography from the official Norwegian scientific webportal (in Norwegian).

- Biography of Thor Heyerdahl

- Sea Routes to Polynesia Extracts from lectures by Thor Heyerdahl