Rachel Dyer

1828 spine label | |

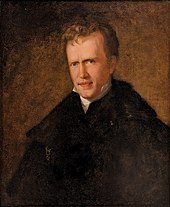

| Author | John Neal |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical fiction Gothic fiction |

| Set in | Salem witch trials |

| Publisher | Shirley and Hyde |

Publication date | 1828 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 276 |

| OCLC | 1049117822 |

| 813.26 | |

Rachel Dyer: A North American Story is a Gothic historical novel by American writer John Neal. Published in 1828 in Maine, it is the first bound novel about the Salem witch trials. Though it garnered little critical notice in its day, it influenced works by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, and Walt Whitman. It is best remembered for the American literary nationalist essay, "Unpublished Preface", that precedes the body of the novel.

Following a darkly poetic narrative, the story centers on historical figure George Burroughs and fictional witch hysteria victim, Rachel Dyer. With about two-thirds of the story taking place in the courtroom, it follows the trials of multiple alleged witches. Themes include justice, sexual frustration, mistreatment of Indigenous Americans by Puritans, the myth of national American unity in the face of pluralist reality, and republican ideals as an antidote for Old World precedent.

Originally written in 1825 as a short story for Blackwood's Magazine, Rachel Dyer was expanded after Neal returned to his hometown, Portland, Maine, from a sojourn in London. He experimented with speech patterns, dialogue, and transcriptions of Yankee dialect, crafting a style for the novel that Neal hoped would come to characterize American literature. Ultimately, the style overshadowed the novel's plot. Rachel Dyer is widely considered to be Neal's most successful novel, with a more controlled construction than his preceding books. A second edition was not released until it was republished by facsimile in 1964.

Plot

[edit]The novel opens with an overview from the narrator of the historical context preceding the Salem witch trials. The narrator describes belief in witchcraft as a universal human trait that was well established amongst educated authorities of the 1690s in both England and its colonies. When Puritans fled persecution in England and colonized New England, they quickly turned to violence to control Quaker colonists and Indigenous Wampanoag. Mary Dyer was executed for her religious convictions and fellow Quaker Elizabeth Hutchinson (based on Anne Hutchinson)[1] cursed their persecutors. A series of events impacting the Massachusetts Bay Colony fulfilled that curse: King Phillip's War, King William's War, epidemics, an earthquake, fires, storms, conflict within the church, and finally, the witch trials. The narrator then introduces the peculiarities of colonial court proceedings and early Puritan leaders, Governor William Phips and Reverend Matthew Paris (based on Samuel Parris).[2]

Paris is grieving for his recently deceased wife. Psychologically vulnerable and superstitious, he centers his life on his ten-year-old daughter, Abigail Paris (based on Betty Parris).[2] She and her twelve-year-old cousin, Bridget Pope (based on Abigail Williams),[2] begin to exhibit what he perceives as demonic behavior. Indigenous neighbors who used to visit the household begin avoiding it and Matthew Paris searches for an explanation. He interrogates Tituba, an enslaved Indigenous household servant who lives in the household with her husband, John Indian. Paris accuses Tituba of witchcraft, and she is arrested, tortured, convicted, and executed. While undergoing torture, she implicates Sarah Good of the same crime in her confession.

Reverend George Burroughs appears at Good's trial. Of mixed European and Indigenous American ancestry and upbringing, Burroughs is a Puritan minister who has been a widower twice. He witnessed the recent Battle of Fort Loyal while serving as minister in Falmouth (now Portland, Maine), but refused to take sides. He escaped injury by mingling into the crowd of Pequot warriors outside the fort, dressed and speaking as a Mohawk. Burroughs defends Good in court and criticizes colonial leaders of breaking treaties and waging unjust war with the Iroquois. Despite Burroughs's defense, Good is convicted and at her execution she proclaims her innocence and prophesies that other innocent victims will be executed. Rachel Dyer (a fictional character not based on any historical figures) appears in the crowd and shouts her support for Sarah Good. Rachel is described as a hunchback with red hair. She and her sister Mary Elizabeth Dyer are Quakers and granddaughters of Mary Dyer, the latter taking her middle name from Elizabeth Hutchinson.

Salem resident Martha Corey is accused of witchcraft. By the time of her trial, many more have been arrested for the same crime, and fear of accusation has swept the town. Burroughs unsuccessfully attempts to defend Corey, who is aloof throughout the trial. Following a speech from Increase Mather, Corey is hanged. Burroughs visits Matthew Paris to investigate the origin of the witch hysteria and finds the household fearful and lifeless. Burroughs then visits the Dyer sisters because of their vocal opposition to the witch hysteria. The three learn that authorities in Salem have issued warrants for their arrest. They flee and are captured en route to the colony of Providence Plantations. While imprisoned and awaiting trial, Burroughs fails to convince the Dyer sisters to issue false confessions in the hope of delaying their own executions until the hysteria passes.

Salem resident Judith Hubbard, who is jealous of Burroughs's affection for Mary Elizabeth Dyer, appears at his trial. She provides spectral evidence by testifying that both of his dead wives have appeared to her as spirits and told her that he murdered them. A boy named Robert Eveleth testifies that Hubbard, Abigail Paris (now dead), and Bridget Pope (who is dying) conspired against Burroughs. Eveleth's testimony is dismissed, and Matthew Paris is going mad and unable to provide corroborating testimony. Burroughs is convicted on Hubbard's testimony but is comforted by Rachel Dyer. She is convicted later the same day. Burroughs is executed and Rachel Dyer dies in her cell clutching a bible. Their martyrdom breaks the witch hysteria before Mary Elizabeth Dyer or anybody else is executed. The final chapter is followed by an appendix labeled "Historical Facts", in which Neal cites connections between first-hand accounts of the witch trials and the circumstances of the story.

Themes

[edit]"They were ministers of the gospel, who ... pursued their brethren to death, scourged, fined, imprisoned, banished, mutilated, and where nothing else would do, hung up their bodies between heaven and earth for the good of their souls".

Many scholars see Rachel Dyer as a story of injustice[4] rooted in the imposition of Old World legal forms upon the free will of New World people.[5] Neal connected the disparate mid-17th-century stories of Quaker dissenters Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer of Boston with the story of the 1692 Salem witch trials. This has been interpreted as a critique of English common law's reliance on precedent[6] by setting up the witch trial story as supernatural retribution for Dyer's and Hutchinson's persecution under unjust laws.[7] As the court's most outspoken opponent, Burroughs questions the judges' rulings and receives in reply: "such was the law, the law of the mother-country and therefore the law of the colonies".[8] But the story centers more on the Dyer sisters' martyrdom, which is presented by Neal as a female tradition of quiet dissent to patriarchal legalism.[9] According to author Donald Sears, juxtaposing crown colonies of the 1690s with republican America of the 1820s highlights the relative value placed on human life in each era.[10] Historian Philip Gould and literature scholars David J. Carlson and Fritz Fleischmann feel the juxtaposition critiques early nineteenth-century American reliance on tradition and hierarchy.[11]

This critique of Puritans as opponents of personal liberty is balanced by Neal's nationalist desire to portray them as a founding body of the US.[12] Neal was at the forefront of the early American literary nationalist movement,[13] which he implies with this novel is deeply connected to the creation of a new legal system that abandons common law through codification.[14] Rachel Dyer was published the same year as Noah Webster's first dictionary. Literature scholar John D. Seelye feels that both books represented a broader literary search for a national American identity.[15] Neal commented on this search by making the greatest opponent to common law in his novel, George Burroughs, of mixed English and Indigenous American ancestry and upbringing.[16] Writing indigenous and racially mixed characters into his novels is one of the ways Neal fashioned his literary nationalist brand.[17]

As a Gothic novel,[18] Rachel Dyer uses gloomy narration, associates dark spaces with immorality, depicts New England forests as the devil's domain, and portrays superstition as the product of rural isolation.[19] Nathaniel Hawthorne cited the novel's Puritan Massachusetts setting as an influence in writing The Scarlet Letter,[20] and Sears argues that Sarah Good's curse from the gallows may have inspired Matthew Maule's curse in Hawthorne's The House of the Seven Gables.[21] After reading Rachel Dyer, John Greenleaf Whittier and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow were inspired to include witchcraft in their poetry and prose.[22]

Neal used the novel's interpretation of republican American values to condemn the treatment of Indigenous Americans by European Americans.[23] He defends Metacomet's legacy from King Philip's War[10] and characterizes the witch hysteria as supernatural retribution for the Puritans' mistreatment of their Indigenous neighbors.[7] Carlson argues that these story elements anticipated many 21st-century historians' characterization of war-related anxieties as a cause of the witch hysteria.[24]

As presented in the novel, Indigenous Americans represent life, though the Puritans associate them with death and dismiss their insight.[25] Neal's choice to give Burroughs a multiracial identity and have him navigate between white and Indigenous worlds is interpreted as a challenge to the concepts of national unity and imperialism.[26] According to Carlson and Edward Watts, Neal used that mixed-race identity to critique colonial America while implying that the mistakes of the 1690s were at risk of being repeated in his own time.[27]

Neal clearly states in the preface that one of his intentions in crafting the novel's title character was to counteract the dominant literary theme that links positive personal attributes with physical beauty, saying "that a towering intellect may inhabit a miserable body".[28] This is a theme he also employed with the character of Hammond in his 1823 novel Errata.[29] Despite her physical deformities,[10] Rachel Dyer demonstrates high morals and commitment to female solidarity in spite of the jealousy she felt at other women's attraction to Burroughs.[30] She also bemoans how differently she may have been treated at trial, had she been more physically attractive.[31] Neal wrote at a time when most critics attacked literature that failed to conform to traditional British conventions, and he intended Rachel Dyer to defy those criticisms.[32]

Sexual frustration is also a theme throughout the novel.[33] Neal links the origin of the witch hysteria to the sexual development of young Bridget Pope,[33] whose bewitched behavior stems from sexual frustration and is calmed too late when she is reunited with her love interest, Robert Eveleth, after the trials have already begun.[34] Matthew Paris is depicted as an isolated, sexually frustrated man.[35] With Tituba and John Indian the only couple in the household, Matthew Paris is threatened by their sexuality, and makes his accusation as a result.[36] Finally, Neal portrays Judith Hubbard's false testimony against Burroughs as revenge for romantic rejection from Burroughs.[37]

Background

[edit]

Neal was one of Blackwood's Magazine's most prolific contributors between 1824 and 1825, while living in London.[38] In 1825, he proposed a series of short stories based in the US, and submitted the first one in October of that year.[39] Scottish publisher William Blackwood accepted the story and paid for it, but delayed publication until Neal demanded it back in February 1826.[40] After returning to his native Portland, Maine, in 1827, he set to work on expanding it, consulting Robert Calef's More Wonders of the Invisible World, which had been republished in 1823.[41] The resulting novel Rachel Dyer is longer, but not substantially different from the original tale, which Neal eventually published as "New-England Witchcraft" in five issues of the New-York Mirror in 1839.[42]

Neal was likely inspired to elevate Burroughs to the role of protagonist in his version of the witch trials story because of Burroughs's stint as minister in Portland (then Falmouth).[43] Both men were also famous for their physical strength.[44] Given these connections, academic Maya Merlob argues that Neal may have felt comfortable filling in many of the unknown details of Burroughs's life with circumstances of his own, making Burroughs into something of a lawyer like himself with persuasive speaking techniques the adolescent Neal learned as a dry goods salesman.[45] Given his interest in history and law, Neal would have been drawn to the Salem court records as research material for the novel.[46] The title character and heroine, however, having no basis in history, he named in honor of his sister, Rachel Wilson Neal.[47]

Like his magazine The Yankee,[48] which also launched in 1828, Rachel Dyer may have been part of Neal's campaign to win back the respect of his hometown, according to author Donald Sears. Many in Portland had rejected him for the unsympathetic characterization of local Portland figures in his earlier novels and for his criticism of American authors in British magazines.[49] According to Neal, he wrote it "hoping it may be regarded by the wise and virtuous of our country as some sort of atonement for the folly and extravagance of my earlier writing".[50] Neal also announced that he was done with novels as an artistic medium. Though he did publish Authorship in 1830 and The Down-Easters in 1833, he wrote first drafts of both novels in London before publishing Rachel Dyer.[51] He did not write another bound novel until True Womanhood in 1859, at the urging of Longfellow, Samuel Austin Allibone, and others in the literary field.[52]

Style

[edit]Do thee mean to confess?

I — I! —

Ah George —

I cannot Rachel — I dare not — I am a preacher of the word of truth. But you may — what is there to hinder you?

Thee will not?

No.

Nor will I.

Dialogue is the predominant vehicle for Neal's experiments with writing style in Rachel Dyer, overshadowing plot and characterization.[54] This is particularly the case in courtroom scenes, which make up two-thirds of the book's length,[54] and that provide a vehicle for demonstrating style elements that Neal felt should come to define American literature.[45]

Neal experimented with a wide range of speech patterns and dialogue techniques, ranging from long, eloquent speeches to short, repetitive murmurs.[55] He omitted quotation marks throughout the novel, feeling they are unnecessary for properly constructed dialogue.[56] Much of the dialogue lacks identifying tags and moves stichomythically back and forth between speakers with little or no interrupting narration.[57] Using crowded, cacophonous courtroom scenes, Neal attempted to paint a picture of a heterogenous nation that dismisses Old World precedent and encourages discourse between races and nationalities.[58]

Like many of his other novels, Neal used Rachel Dyer to experiment with phonetic transcriptions of Yankee dialect, which is assigned to minor characters like Robert Eveleth, the court bailiff, and frontier townsfolk at the Battle of Fort Loyal.[59] This is Neal's attempt at literary realism[29] and at conceptualizing the US as a culturally diverse place.[60] This pioneering effort to document regional American dialect was cited in the first edition of the Dictionary of American English more than a century later.[61]

"Unpublished Preface"

[edit]Rachel Dyer starts with a three-page preface and a fifteen-page essay titled "Unpublished Preface to the North-American Stories".[62] Neal wrote the latter in 1825 for Blackwood's Magazine as an introductory essay to a series of short stories, but the editor rejected it.[63] The essay is a manifesto for American literary nationalism, a movement of which Neal was at the forefront in the 1820s.[64] The product of one of the most aggressive among early literary nationalists, per scholar Ellen Bufford Welch,[13] the essay is far better known among modern critics and scholars than the novel to which it is attached.[65] Literature scholar Hans-Joachim Lang republished it in 1962 in the German journal Amerikastudien.[66]

The "Unpublished Preface" recognizes efforts by other American novelists to explore American places and characters, but criticizes them for failing to help develop new linguistic and formal styles.[67] This could be achieved, Neal argued, through experimentation with American colloquialism, speech patterns, and regional accents.[68] Contending that American novelists relied too much on British precedent,[67] he charged Washington Irving with copying Joseph Addison and James Fenimore Cooper with copying Walter Scott. Neal said: "I shall never write what is now worshipped under the name of classical English ... the deadest language I ever met with".[69]

Neal also advanced cultural pluralism in the essay, criticizing his literary peers for limiting themselves to white characters as representative of the American identity.[70] He blamed them for helping advance Jacksonian values on the rise at the time: manifest destiny, empire building, Indian removal, consolidation of federal power, racialized citizenship, and the Cult of Domesticity. Unlike Neal's earlier literary nationalist works that portrayed the US as a unified nation, the "Unpublished Preface" represents the author's movement toward American literary regionalism in reaction to Jacksonian populism, according to Watts and Carlson.[71]

Like the novel itself, the "Unpublished Preface" rejects precedent,[65] calling for "another Declaration of Independence, in the Great Republic of Letters".[72] This is a theme for which Neal was well-known at the time[27] and that ran through all seven of Neal's previously published novels,[73] many of which included literary nationalist statements in their prefaces.[64] However, the essay also used the relatively uncontroversial concept of literary nationalism to advance the more controversial push among radical American lawyers to abandon English Common law.[74]

This nationalist/regionalist challenge likely inspired Walt Whitman to write Leaves of Grass twenty-seven years later, according to author Benjamin Lease.[75] Whitman likely read Rachel Dyer as a boy. Years later he interacted with Neal as a regular contributor to Brother Jonathan magazine while Neal was editor in 1843.[76]

Publication history

[edit]Rachel Dyer is the first fictionalized account of the Salem witch trials story in a bound novel, being preceded only by Salem, an Eastern Tale (1820), which was published anonymously to little notice and low distribution in serial form by a New York City literary journal.[77] Neal's novel was published in Portland, Maine, in 1828,[78] and never saw a second edition in his lifetime; it was first republished, by facsimile with an original introduction by John D. Seelye, in 1964.[79] This was the first of Neal's major novels to be republished since Seventy-Six was republished in London in 1840.[80] However, it was the fourth major work by Neal republished in the twentieth century, starting with American Writers in 1937.[81]

Reception

[edit]Period critique

[edit]

Rachel Dyer was an obscure novel when it was published, attracting little critical attention in the US and virtually none in the UK for years.[82] Referring to the novel's comparatively focused construction, one American reviewer said five months after publication that it "has fewer of the peculiarities of its peculiar author".[83] A British critic, while reviewing Neal's next novel Authorship in 1831, offered brief and lukewarm praise of the earlier work by referring to Burroughs as "the wild preacher of the woods ... a personage worthy of the dramatic era of Elizabeth".[84] The critic concluded that Neal "exults the name of Yankee, and Yankees should be proud of him".[85] Neal also published two reviews of his own novel in his magazine The Yankee.[86] Speaking of himself in the third person, he repeated a sentiment in the "Unpublished Preface" that it is his best work, but that he is capable of better: "It is the best thing of the sort ever produced by John Neal, though not altogether such a work as might have been hoped for by his countrymen."[87] The other Yankee review was written by a friend, who anticipated the prevailing sentiment amongst modern scholars that Rachel Dyer represents Neal's best effort to date to control his own expansive proclivities. According to him: "Wherever Neal's imagination has been employed throughout the work, it has been more temperate and rational than on any former occasion of the kind."[88]

Years later, the novel was praised by Whittier and Longfellow, who both received their first impactful encouragement in The Yankee.[89] Whittier praised the opening chapters as "magnificent poetry" that certainly sprang from Neal's deep convictions.[90] In 1868, Longfellow wrote brief and mixed praise in his private journal: "Read John Neal's Rachel Dyer, a tale of Witchcraft. Some parts very powerful."[91]

Modern views

[edit]Contemporary scholars of John Neal's novels widely consider Rachel Dyer to be his most successful,[92] though it is as obscure to the modern reader as his other books.[93] Biographer Donald A. Sears specifically points to the novel's depth of characterization, skilled phonetic transcription of regional accents, and experiments with dialogue.[94] Both he and Fleischmann claim that the work fulfilled the literary nationalist call of the "Unpublished Preface" better than any other by Neal.[95] Biographer Benjamin Lease feels that, while Hawthorne and Herman Melville used the same themes years later to produce better novels, "in 1828, Rachel Dyer stands alone".[96] Lease and Lang compared it to the 1953 play The Crucible, claiming Neal's work matched the play in dramatic effect, but surpassed it in sophistication.[97]

When praising Rachel Dyer, many scholars focus on the story's construction. Compared to Neal's earlier novels, Alexander Cowie celebrated that "Neal for once abandoned his literary monkeyshines",[93] Fleischmann calls it "carefully controlled",[98] Lease says it was "far more concentrated in effect",[99] Sears says it was "written with better control",[43] Lang claims it has "more concentrated power",[4] and Seelye writes in the introduction to the 1964 republication that the story has more "control and warmth".[100] Lease, however, tempers his praise of the novel's powerful and well-constructed elements, critiquing the more excessive parts of the novel, particularly the courtroom scenes, "where the lawyer in Neal gets somewhat the better of the novelist."[101] Irving T. Richards goes further, claiming that Rachel Dyer suffers from "absurd extravagances" that are "especially obnoxious" given the grave chapter of American history it represents.[102] He feels that the strength of the story's construction comes more from the absence of wandering excesses than the presence of a unified theme.[103] Whereas most scholars posit that Neal subdued his natural expansive tendencies in order to write Rachel Dyer, Maya Merlob argues that his more erratic works represent as much an intentionally chosen model as this novel does.[104]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Gould 1996, p. 203.

- ^ a b c Richards 1933, p. 697n2.

- ^ Neal 1964, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Lease & Lang 1978, p. xxiii.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 295.

- ^ Carlson 2007, pp. 408–409.

- ^ a b Lease 1972, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, pp. 307–308, quoting Rachel Dyer.

- ^ Fleischmann 1987, p. 164.

- ^ a b c Sears 1978, p. 81.

- ^ Gould 1996, p. 205; Carlson 2007, pp. 409, 427n11; Fleischmann 1983, p. 317.

- ^ Gould 1996, pp. 18–19, 175–176.

- ^ a b Welch 2021, p. 473.

- ^ Carlson 2007, pp. 407, 409, 427n11.

- ^ Seelye 1964, p. xi.

- ^ Seelye 1964, p. xi; Richards 1933, p. 699.

- ^ Goddu 1997, p. 58.

- ^ Welch 2021, p. 471; Carlson 2007, p. 407.

- ^ Lease 1972, pp. 143–144; Sears 1978, p. 82.

- ^ Kayorie 2019, p. 90; Seelye 1964, p. xii; Lease 1972, p. 137.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 83.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 137; Sears 1978, p. 82.

- ^ Watts 2012, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Carlson 2007, p. 422.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, pp. 305, 317.

- ^ Pethers 2012, pp. 24–25; Davis 2007, p. 66.

- ^ a b Watts & Carlson 2012b, p. xviii.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 80, quoting Rachel Dyer.

- ^ a b Richards 1933, p. 703.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 313.

- ^ Cowie 1948, p. 783n34.

- ^ Carlson 2007, p. 416.

- ^ a b Fleischmann 1983, p. 301.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 311.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 302.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 303.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 84; Fleischmann 1983, p. 301.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 50; Sears 1978, p. 71.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 495–496.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 495–496, 498–499.

- ^ Gould 1996, p. 203; Carlson 2007, p. 426n7; Sears 1978.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 920.

- ^ a b Sears 1978, p. 79.

- ^ Seelye 1964, pp. viii–x.

- ^ a b Merlob 2012, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Sears 1978, pp. 79, 137n1, 137n2.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 319.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 112; Richards 1933, p. 577.

- ^ Sears 1978, pp. 79–80, 137–138n3.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 294, quoting the preface to Rachel Dyer.

- ^ Lease 1972, pp. 146, 159.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 11; Richards 1933, pp. 1181–1182.

- ^ Neal 1964, p. 257.

- ^ a b Pethers 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 144.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 705.

- ^ Pethers 2012, p. 24; Lease 1972, p. 144.

- ^ Davis 2007, p. 66; Carlson 2007, pp. 418, 430n29.

- ^ Lease 1972, pp. 144, 153.

- ^ Pethers 2012, pp. 12, 27.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 189.

- ^ Neal 1964, pp. iii–xx.

- ^ Lease & Lang 1978, p. xxi.

- ^ a b Welch 2021, p. 471.

- ^ a b Carlson 2007, p. 406.

- ^ Neal, Lang & Richards 1962, p. 204.

- ^ a b Welch 2021, p. 474.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 694–695.

- ^ Lease 1972, pp. 143–144, quoting the "Unpublished Preface".

- ^ Watts 2012, p. 213.

- ^ Watts & Carlson 2012b, p. xxi.

- ^ Pethers 2012, p. 3, quoting the "Unpublished Preface".

- ^ Pethers 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Carlson 2007, pp. 414–415.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 79.

- ^ Rubin 1941, p. 183.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 82.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 11.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 34.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 203.

- ^ Halfmann 1990, pp. 431, 431n8.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 695.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 146, quoting the reviewer.

- ^ Lease 1972, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Cairns 1922, p. 213.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 147.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 293; Richards 1933, p. 695, quoting Neal in The Yankee.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 696, quoting "Strafford" in The Yankee.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 129.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 86; Lease 1972, p. 145, quoting John Greenleaf Whittier.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 137, quoting Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 703; Fleischmann 1983, p. 13; Seelye 1964, p. viii; Watts & Carlson 2012b, p. xviii; Cowie 1948, p. 173.

- ^ a b Cowie 1948, p. 175.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 84.

- ^ Sears 1978, p. 84; Fleischmann 1983, p. 295.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 145.

- ^ Lease & Lang 1978, p. 283.

- ^ Fleischmann 1983, p. 293.

- ^ Lease 1972, p. 138.

- ^ Seelye 1964, p. viii.

- ^ Lease 1972, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Richards 1933, p. 704.

- ^ Richards 1933, pp. 703–704.

- ^ Merlob 2012, p. 120n11.

Sources

[edit]- Cairns, William B. (1922). British Criticisms of American Writings 1815–1833: A Contribution to the Study of Anglo-American Literary Relationships. University of Wisconsin Studies in Language and Literature Number 14. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin. OCLC 1833885.

- Carlson, David J. (2007). "'Another Declaration of Independence': John Neal's 'Rachel Dyer' and the Assault on Precedent". Early American Literature. 42 (3): 405–434. doi:10.1353/eal.2007.0031. JSTOR 25057515. S2CID 159478165.

- Cowie, Alexander (1948). The Rise of the American Novel. New York City, New York: American Book Company. OCLC 268679.

- Davis, Theo (2007). Formalism, Experience, and the Making of American Literature in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511551000. ISBN 978-1-139-46656-1.

- DiMercurio, Catherine C., ed. (2018). Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism: Criticism of the Works of Novelists, Philosophers, and Other Creative Writers Who Died between 1800 and 1899, from the First Published Critical Appraisals to Current Evaluations. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale, A Cengage Company. ISBN 978-1-4103-7851-4.

- Fleischmann, Fritz (1983). A Right View of the Subject: Feminism in the Works of Charles Brockden Brown and John Neal. Erlangen, Germany: Verlag Palm & Enke Erlangen. ISBN 978-3-7896-0147-7.

- Fleischmann, Fritz (1987). "Yankee Heroics: New England Folk Life and Character in the Fiction of Portland's John Neal (1793–1876)". In Vaughan, David K. (ed.). Consumable Goods: Papers from the North East Popular Culture Association Meeting, 1986. Orono, Maine: National Poetry Foundation, University of Maine. pp. 157–165. ISBN 0943373026.

- Goddu, Theresa A. (1997). Gothic America: Narrative, History, and Nation. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10817-1.

- Gould, Philip (1996). Covenant and Republic: Historical Romance and the Politics of Puritanism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511585449. ISBN 0-521-55499-3.

- Halfmann, Ulrich (September 1990). "In Search of the 'Real North American Story': John Neal's Short Stories 'Otter-Bag' and 'David Whicher'". The New England Quarterly. 63 (3): 429–445.

- Kayorie, James Stephen Merritt (2019). "John Neal (1793–1876)". In Baumgartner, Jody C. (ed.). American Political Humor: Masters of Satire and Their Impact on U.S. Policy and Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 86–91. ISBN 978-1-4408-5486-6.

- Lease, Benjamin (1972). That Wild Fellow John Neal and the American Literary Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-46969-0.

- Lease, Benjamin; Lang, Hans-Joachim, eds. (1978). The Genius of John Neal: Selections from His Writings. Las Vegas: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-261-02382-7.

- Merlob, Maya (2012). "Celebrated Rubbish: John Neal and the Commercialization of Early American Romanticism". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. 99–122. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Neal, John; Lang, Hans-Joachim; Richards, Irving T. (1962). "Critical Essays and Stories by John Neal". Jahrbuch für Amerikastudien. 7: 204–319. JSTOR 41155013.

- Neal, John (1964). Rachel Dyer: A North American Story. Gainesville, Florida: Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints. OCLC 468770740. Facsimile reproduction of 1828 edition.

- Pethers, Matthew (2012). "'I Must Resemble Nobody': John Neal, Genre, and the Making of American Literary Nationalism". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. 1–38. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Richards, Irving T. (1933). The Life and Works of John Neal (PhD thesis). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. OCLC 7588473.

- Rubin, Joseph Jay (1941) [Originally published in The New England Quarterly, vol. 14, no. 2. pp. 359–362]. "John Neal's Poetics as an Influence on Whitman and Poe". Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism: Criticism of the Works of Novelists, Philosophers, and Other Creative Writers Who Died between 1800 and 1899, from the First Published Critical Appraisals to Current Evaluations. pp. 183–184. In DiMercurio (2018).

- Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-7230-2.

- Seelye, John D. (1964). "Introduction". Rachel Dyer: A North American Story. pp. v–xii. In Neal (1964).

- Watts, Edward (2012). "He Could Not Believe that Butchering Red Men Was Serving Our Maker: 'David Whicher' and the Indian Hater Tradition". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. 209–226. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Watts, Edward; Carlson, David J., eds. (2012a). John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. Lewisburg, Pennsylvania: Bucknell University Press. ISBN 978-1-61148-420-5.

- Watts, Edward; Carlson, David J. (2012b). "Introduction". John Neal and Nineteenth Century American Literature and Culture. pp. xi–xxxiv. In Watts & Carlson (2012a).

- Welch, Ellen Bufford (2021). "Literary Nationalism and the Renunciation of the British Gothic Tradition in the Novels of John Neal". Early American Literature. 56 (2): 471–497. doi:10.1353/eal.2021.0039. S2CID 243142175.

External links

[edit]- Rachel Dyer original 1828 edition available at Google Books

- Rachel Dyer: A North American story at Project Gutenberg

- Rachel Dyer original 1828 edition available at Internet Archive

- 1828 American novels

- American gothic novels

- American historical novels

- Books by John Neal (writer)

- King Philip's War

- King William's War

- Novels set in Massachusetts

- Novels set in the 1690s

- Salem witch trials in fiction

- Native Americans in popular culture

- Novels set in the American colonial era

- Novels set in courtrooms