User:Andytheicandy/sandbox

Labrador Husky

[edit]The Labrador Husky is a spitz type of dog that was bred for work as a very strong, fast sled dog; it is a purebred originating from Canada. Although the breed's name may be baffling, it is not a mix between a Labrador Retriever and a husky. The breed is very little known, and there are no breed clubs that currently recognize it.

The Labrador Husky is a spitz purebred sled dog originating from Newfoundland and Labrador, a Canadian province. It is believed to be first developed by the Thule Inuit people between 1250 AD and 1450 AD.[1] This intelligent breed is similar in size and weight as a Siberian Husky however, the breed is not a mix between a Labrador Retriever and a Husky.

The Labrador Husky is a breed of sled dogs originally developed in Canada for sledding over long distances across rough snowy terrain. This breed is a medium-sized to large-sized, double-coated dog that occurs in two general color forms. As with dogs from other sledding breeds, the Labrador Husky is energetic and intelligent. It responds well to structured training, particularly if it is interesting and challenging. It forms a strong attachment to its owners, and can be protective of them and their possessions.

The biggest step in a successful article is with some main points that need to be covered with any biography of a music group. History and name origin, early years, band legacy. Members, awards (if any) , music/songs/albums. All information should be cited accordingly. There also needs to be clear communication from writer to reader. No arguments are needed and no to bias writing. write about the history of the band and all major topics surrounding the band.

I think the most important step to a good Wikipedia article is having the right sources. For example, in the article about AC/DC there were 133 sources cited in the article. Most were articles from credible websites like Rollingstone.com and AC/DC’s own website. Information can be taken from all these sources and still not make a great article. It is up to the writer to use the information they just witnessed to make a biography.

Just because there are 133 sources doesn’t mean every source is the best and is the most credible. Sources should be read numerous times and evaluated. There should be a reason for the inclusion of this source. For example, an article writes on a band member that had past away. Think of why this is important to the article. In the case with AC/DC they stated that the passing of a member added motivation for creating better music. The articles length should be from 5,000 to 8,000 words. The article shouldn't be too long making it drag or too short not covering enough information.The talk page should be well organized allowing for communication.

History

[edit]There is a band you are covering. So think and evaluate what you need to cover. Band Members. Create a small introduction about each member. Present how this person is important or when did they join the band? Major Songs or Albums? Crime involved? or perhaps drug use? Present unbiased backstories of the band members to continue the article. History in the name? If its an older band present the different decades in which they had a successful year and what not.

Timeline

[edit]The article should be arranged in a timeline format.. After the introduction, present major plot points in the bands history. Success, Deaths, Rebirth are all good examples.

After the article is finished create a legacy paragraph and write the legacy the band had.

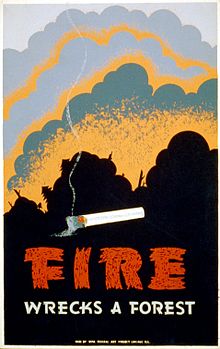

Wildfires are a common problem for Americans especially for those who live in California and southern areas near. Policies have been implemented starting in 1908 with the Forest Fire Emergency Fund Act. Since then numerous policies have been in place such as the "10AM Policy". FEMA and NFPA created policies to help with damages to buildings and houses. The U.S. Army and U.S. Forest Service also take part in preserving timber. Wildfires were seen to be a major problem. Smokey the Bear was introduced to the pubic to spread awareness to adolescence. Wildfires have been a problem for years and the most notable fire recently was the 2016 Nevada Wildfires.

History of wildfire policy in the U.S.

[edit]Since the turn of the 20th century, various federal and state agencies have been involved in wildland fire management in one form or another. In the early 20th century, for example, the federal government, through the U.S. Army and the U.S. Forest Service, solicited fire suppression as a primary goal of managing the nation's forests. At this time in history fire was viewed as a threat to timber, an economically important natural resource. As such, the decision was made to devote public funds to fire suppression and fire prevention efforts. For example, the Forest Fire Emergency Fund Act of 1908 permitted deficit spending in the case of emergency fire situations.[2] As a result, the U.S. Forest Service was able to acquire a deficit of over $1 million in 1910 due to emergency fire suppression efforts.[2] Following the same tone of timber resource protection, the U.S. Forest Service adopted the "10 AM Policy" in 1935.[2] Through this policy, the agency advocated the control of all fires by 10 o'clock of the morning following the discovery of a wildfire. Fire prevention was also heavily advocated through public education campaigns such as Smokey Bear. Through these and similar public education campaigns the general public was, in a sense, trained to perceive all wildfire as a threat to civilized society and natural resources. The negative sentiment towards wildland fire prevailed and helped to shape wildland fire management objectives throughout most of the 20th century.

Beginning in the 1970s public perception of wildland fire management began to shift.[2] Despite strong funding for fire suppression in the first half of the 20th century, massive wildfires continued to be prevalent across the landscape of North America. Ecologists were beginning to recognize the presence and ecological importance of natural, lightning-ignited wildfires across the United States. It was learned that suppression of fire in certain ecosystems may in fact increase the likelihood that a wildfire will occur and may increase the intensity of those wildfires. With the emergence of fire ecology as a science also came an effort to apply fire to ecosystems in a controlled manner; however, suppression is still the main tactic when a fire is set by a human or if it threatens life or property.[3] By the 1980s, in light of this new understanding, funding efforts began to support prescribed burning in order to prevent wildfire events.[2] In 2001, the United States implemented a National Fire Plan, increasing the budget for the reduction of hazardous fuels from $108 million in 2000 to $401 million.[3]

In addition to using prescribed fire to reduce the chance of catastrophic wildfires, mechanical methods have recently been adopted as well. Mechanical methods include the use of chippers and other machinery to remove hazardous fuels and thereby reduce the risk of wildfire events. Today the United States' maintains that, "fire, as a critical natural process, will be integrated into land and resource management plans and activities on a landscape scale, and across agency boundaries. Response to wildfire is based on ecological, social and legal consequences of fire. The circumstance under which a fire occurs, and the likely consequences and public safety and welfare, natural and cultural resources, and values to be protected dictate the appropriate management response to fire" (United States Department of Agriculture Guidance for Implementation of Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy, 13 February 2009). The five federal regulatory agencies managing forest fire response and planning for 676 million acres in the United States are the Department of the Interior, the Bureau of Land Management, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the National Park Service, the United States Department of Agriculture-Forest Service and the United States Fish and Wildlife Services. Several hundred million U.S. acres of wildfire management are also conducted by state, county, and local fire management organizations.[4] In 2014, legislators proposed The Wildfire Disaster Funding Act to provide $2.7 billion fund appropriated by congress for the USDA and Department of Interior to use in fire suppression. The bill is a reaction to United States Forest Service and Department of Interior costs of Western Wildfire suppression appending that amounted to $3.5 billion in 2013.[5]

Wildland-urban interface policy

[edit]An aspect of wildfire policy that is gaining attention is the wildland-urban interface (WUI). More and more people are living in "red zones," or areas that are at high risk of wildfires. FEMA and the NFPA develop specific policies to guide homeowners and builders in how to build and maintain structures at the WUI and how protect against property losses. For example, NFPA-1141 is a standard for fire protection infrastructure for land development in wildland, rural and suburban areas[6] and NFPA-1144 is a standard for reducing structure ignition hazards from wildland fire.[7] For a full list of these policies and guidelines, see http://www.nfpa.org/categoryList.asp?categoryID=124&URL=Codes%20&%20Standards. Compensation for losses in the WUI are typically negotiated on an incident-by-incident basis. This is generating discussion about the burden of responsibility for funding and fighting a fire in the WUI, in that, if a resident chooses to live in a known red zone, should he or she retain a higher level of responsibility for funding home protection against wildfires. One initiative aimed at helping U.S. WUI communities live more safely with fire is called fire-adapted communities.

Economics of fire management policy

[edit]Similar to that of military operations, fire management is often very expensive in the U.S. and the rest of the world. Today, it is not uncommon for suppression operations for a single wildfire to exceed costs of $1 million in just a few days. The United States Department of Agriculture allotted $2.2 billion for wildfire management in 2012.[8] Although fire suppression purports to benefit society, other options for fire management exist. While these options cannot completely replace fire suppression as a fire management tool, other options can play an important role in overall fire management and can therefore affect the costs of fire suppression.

Fire suppression and climate change has resulted in larger, more intense wildfire events which are seen today.[9] In economic terms, expenditures used for wildfire suppression in the early 20th century have contributed to increased suppression costs which are being realized today.[9]

Regional burden of wildfires in the United States

[edit]

Nationally, the burden of wildfires is disproportionally heavily distributed in the southern and western regions. The Geographic Area Coordinating Group (GACG)[10] divides the United States and Alaska into 11 geographic areas for the purpose of emergency incident management. One particular area of focus is wildland fires. A national assessment of wildfire risk in the United States based on GACG identified regions (with the slight modification of combining Southern and Northern California, and the West and East Basin); indicate that California (50.22% risk) and the Southern Area (15.53% risk) are the geographic areas with the highest wildfire risk.[11] The western areas of the nation are experiencing an expansion of human development into and beyond what is called the wildland-urban interface (WUI). When wildfires inevitably occur in these fire-prone areas, often communities are threatened due to their proximity to fire-prone forest.[12] The south is one of the fastest growing regions with 88 million acres classified as WUI. The south consistently has the highest number of wildfires per year. More than 50,000 communities are estimated to be at high to very high risk of wildfire damage. These statistics are greatly attributable to the South's year-round fire season.[13]

Notable wildfires in the United States

[edit](Chronological)

- Peshtigo Fire, 1871; most loss of life in a US wildfire.

- Great Fire of 1910 in the US; shaped 20th-century wildfire policy

- 1988 Yellowstone wildfires

- 2011 Texas wildfires

- 2013 Beaver Creek Fire in Idaho.

- 2016 Nevada wildfire[14]

See also

[edit]- ^ "Labrador Husky - Sarah's Dogs". www.sarahsdogs.com. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ^ a b c d e Pyne, S.J. 1984. Introduction to wildland fire: Fire management in the United States. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- ^ a b Stephens, Scott L.; Ruth (2005). "Federal Forest Fire Policy in US". Ecological Application. 15 (2): 532–542. doi:10.1890/04-0545.

- ^ "National Interagency Fire Center". Nifc.gov. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Graff, Trevor. "Congressional wildfire bill would adjust state wildland fire funding". Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ "NFPA 1141: Standard for Fire Protection Infrastructure for Land Development in Wildland, Rural, and Suburban Areas". Nfpa.org. 31 May 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "NFPA 1144: Standard for Reducing Structure Ignition Hazards from Wildland Fire". Nfpa.org. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ United States Department of Agriculture . FY 2012 Budget Summary

- ^ a b Western Forestry Leadership Coalition (2010). "The true cost of wildfire in the western U.S." (PDF). Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ "National Geographic Area Coordination Center Website Portal". Gacc.nifc.gov. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Ager, A.A.; Calkin, P.E.; Finney, M.A.; Gilbertson-Day, J.W.; Thompson, M.P. (2011). "Integrated national-scale assessment of wildfire risk to human and ecological values". Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment. 25: 1–20. doi:10.1007/s00477-011-0461-0.

- ^ USDA Forest Service. 2011. Wildland fire and fuels fesearch and development strategic plan: Meeting the needs of the present, anticipating the needs of the Future. FS0854

- ^ Hoyle, Z. (2009). "The southern wildlife risk assessment: A powerful new tool for fighting fire in the south". Compass. 18: 12–14. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ http://www.foxnews.com/us/2016/08/02/wildfires-burn-in-7-western-states-prompt-evacuations0.html

| This is a user sandbox of Andytheicandy. You can use it for testing or practicing edits. This is not the sandbox where you should draft your assigned article for a dashboard.wikiedu.org course. To find the right sandbox for your assignment, visit your Dashboard course page and follow the Sandbox Draft link for your assigned article in the My Articles section. |