User:Nishkid64/Buford Expedition

Background[edit]

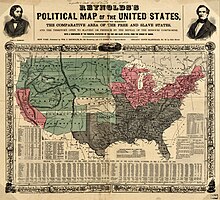

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 created the territories of Nebraska and Kansas. This Act, which reopened controversy over slavery that the 1820 Missouri Compromise had resolved, included the principle now known as "popular sovereignty", an idea advocated by U.S. Senator Stephen A. Douglas, chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, which would let matters involving slavery be decided by the inhabitants of the territories.[1] Popular sovereignty was an attempt to offer concessions to the southern states by making the expansion of slavery possible into both western and northern territories.[2][3][4]

The southern states had conceded their efforts to form a majority in Nebraska early on, after it appeared that there was a large enough anti-slavery voting bloc to guarantee the territory's admission as a free state.[5] The settlement and the zone formation of the state government in Kansas became highly politicized beyond the borders of the territory. As Republican Senator William H. Seward of New York proclaimed, "[w]e will engage in competition for the virgin soil of Kansas."[3] Democratic Senator David Rice Atchison of Missouri remarked to his colleagues from the South, "[w]e are playing for a might stake. The game must be played boldly. ... If we win we can carry slavery to the Pacific Ocean, if we fail we lose Missouri, Arkansas, Texas and all the territories."[3] Missouri, a slave state, was uniquely exposed to free states, with Illinois and Iowa bordering it on the east and north. Most parts of Missouri held very few slaves, and slave owners accounted for a very small proportion of the state's population. If Kansas entered the Union as a free state, Missouri would have free soil on three sides. Since manumission, abolition activity, and escape were all more common in the border south, Southerners felt that the existence of nearby free soil was a threat to Missouri slaveowners. Senator Atchison told Democratic Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi that Southerners "are organizing. We will be compelled to shoot, burn, & hang, but the thing will soon be over."[6]

The first organized immigration to Kansas Territory was by citizens of southern states, most notably neighboring Missouri, who came to the territory to secure the expansion of slavery.[6] Pro-slavery settlements were established by these immigrants at Leavenworth, Lecompton, and Atchison. Anti-slavery leaders were uncertain if they would have a strong enough presence to ensure its entrance into the Union as a free state. However, they did not plan on giving up the fight in Kansas so easily, so they launched a massive recruiting campaign, through organizations, such as the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company, to bring immigrants to the territory to shift the balance of power.[3][5][7] These organizations helped establish free-state settlements further into the territory, in Topeka, Manhattan, and Lawrence.[6]

In 1855, Atchison led a group of border ruffians across the Missouri border to vote illegally in Kansas's first legislative election. Although a subsequent congressional investigation found that 4,908 of the 6,318 votes cast were fraudulent, the pro-slavery legislature kept their seats.[6] By the end of 1855, the Emigrant Aid Societies had accounted for lost ground, and the prospect of Kansas becoming a pro-slavery state looked bleak.[5]

Buford heeds the call for help[edit]

Border ruffians in Missouri immediately appealed to Southern states, asking slavery proponents to emigrate to Kansas to help win the election. In the Montgomery, Alabama Advertiser and Gazette, the border ruffians issued the following appeal:

But the time has come when she [Missouri] can no longer stand up single-handed, the lone champion of the South, against the myrmidons of the South. It requires no foresight to perceive that if the 'higher law' men succeed in this crusade, it will be but the beginning of a war upon the institutions of the South, which will continue until slavery shall cease to exist in any of the states, or the Union is dissolved.

The great struggle will come off at the next election in October, 1856, and unless at that time the South can maintain her ground all will be lost. We repeat it, the Crisis has arrived. The time has come for action—bold, determined action. Words will no longer do any good; we must have men in Kansas, and that by tens of thousands. A few will not answer. If we should need ten thousand men and lack one of that number, all will count nothing. Let all then who can come do so at once. Those who cannot come must give their money to help others to come. ... We tell you know, and tell you frankly, that unless you come quickly, and come by thousands, we are gone. The elections once lost are lost forever.[8]

They believed that if Kansas entered the union as a free state, other states would follow suit, starting with Missouri and other states west of the Mississippi River and moving eastward until the pro-slavery bloc was localized to the south Atlantic region.[9][10] Pro-slavery emigrant aid societies immediately formed in the South and began recruitment campaigns. In early November, a citizen named Thomas J. Orme proposed to send 500 settlers to Kansas if people could raise US$100,000 to fund the move.[10] Orme's proposition did not stir any interest,[11] but another proposal six days later, on November 26, 1855, made by Major Jefferson Buford, a lawyer from Eufaula, received considerable attention:[12]

To Kansas Emigrants— Who will go to Kansas? I wish to raise three hundred industrious, sober, discreet, reliable men capable of bearing arms, not prone to use them wickedly or unnecessarily, but willing to protect their sections in every real emergency. I desire to start with them for Kansas by the 20th of February next. To such I will guaranty the donation of a homestead of forty acres of first rate land, a free passage to Kansas and the means of support for one year. To ministers of the gospel, mechanics, and those with good military or agricultural outfits, I will offer greater inducements. Besides devoting twenty thousand dollars of my own means to this enterprise I expect all those who know and have confidence in me and who feel an interest in the cause, to contribute as much as they are able. I will give to each contributor my obligation that for every fifty dollars contributed I will within six months thereafter place in Kansas one bona fide settler, able and willing to vote and fight if need be for our section, or in default of doing so, that I will on demand refund the donation with interest from the day of its receipt. I will keep an account of the obligations so issued, and each successive one shall specify one emigrant more than its immediate predecessor,—thus: No. 1 shall pledge me to take one emigrant; No. 2, two; No. 3, three, etc., and if the state makes a contribution it shall be divided into sums of fifty dollars each and numbered accordingly. Here is your cheapest and surest chance to do something for Kansas,—something toward holding against the free-soil hordes that great Thermopylae of Southern institutions. In this their great day of darkness, nay, of extreme peril, there ought to be, there needs must be great individual self-sacrifice, or they cannot be maintained. If we cannot find many who are willing to incur great individual loss in the common cause, if we cannot find some crazy enough to peril even life in the deadly breach, then it is not because individuals have grown more prudent and wise, but because public virtue has decayed and we have thereby already become unequal to the successful defense of our rights.[13]

Organizing the expedition[edit]

Within days, Buford stated that he had already found a number prospective settlers, who he described as "honest, clever, poor young men from the country, used to agricultural labor, with a few merchants, mechanics, printers, and carpenters."[14] Buford organized the party of prospective settlers ?in military fashion: those who held the rank of captain or higher in military service would maintain their status in the group, while officers below the rank of captain would have to be elected by a vote from their fellow settlers.[14] If need be, the emigrants could also vote to expel a member from the group. ?Buford set up four rendezvous points—Eufaula, Seale, Montgomery and Columbus, Georgia—where members would assemble to be kept up to date with Buford's plans and to receive their issue of rations.[14][15] On the return trip back to Alabama, Buford planned to write a report detailing each settler's name, where they were enrolled and where they were dropped off in Kansas.[14]

To finance the party's voyage to Kansas, Buford asked slavery advocates to offer donations for the cause. He said, "I am not rich and have found no money, but have made what little I possess—have four small children of tender age to support, and, with less at stake than thousands of others, am only battling for our common section, against a powerful, untiring, fanatical enemy, who, fighting as he thinks for humanity, is in fact bringing degradation, desolation and woe to our beloved South."[11] Buford announced that for every fifty dollars that was contributed to his cause, he would, as initially described in his open letter in the Eufaula, Alabama Spirit of the South, take one emigrant to Kansas, give him forty acres of land and keep him there for a year. The offer trumped the gimmicks used by the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company to lure emigrants and donors.[16] ?To support his plan, Buford sold forty of his plantation slaves on January 7, 1856 in Montgomery and placed the over US$20,000 in proceeds in an expense fund for the expedition. Buford also lobbied the Alabama state legislature to appropriate $25,000 to finance the costs of the expedition. The bill was introduced in the legislature by Representative F. K. Beck of Wilcox County and referred to the Committee on Federal Relations, but the matter was never discussed.[16][17][18]

On behalf of Buford, noted leaders, such as William Lowndes Yancey, Alpheus Baker, Henry DeLamar Clayton, LeRoy Pope Walker and Henry W. Hilliard delivered speeches, asking Alabamans to protect "Southern rights on the Kansas battleground". In addition, Buford appointed Yancey in charge of receiving donations for the expedition.[17] In early January 1856, William T. Merrifield, a free state proponent from Worcester, Massachusetts was in Montgomery at the time and heard news of Buford's planned expedition. He immediately returned back to his hometown and informed Eli Thayer, the founder of the Massachusetts Emigrant Aid Company, of Buford's plans. Thayer immediately arranged a 165-man force armed with Beecher's Bibles (Sharps rifles) and sent them off to Kansas to fight the Southern force.[16][17][19] Buford intended to also arm his party of settlers, but in March 1856, he announced that, in light of President Franklin Pierce's February 11 proclamation calling for peace in the Kansas Territory between the two sides, he would leave the group unarmed.[17][20]

Embarking on the expedition[edit]

On March 31, 1856, one group of prospective settlers left the meeting place in Eufaula and began their journey to Montgomery. Along the way, they passed through Columbus, Georgia, and picked up the 50-man company that had been waiting there. Buford led his men into Montgomery on April 4, where they collected the final company of emigrants. In all, there were approximately 400 prospective settlers—one hundred from South Carolina, fifty from Georgia, one each from Illinois and Boston and the rest from Alabama.[21]

That day, the people of Montgomery held a reception for the emigrants at Estelle Hall.[22] Alpheus Baker delivered a inspirational speech to the emigrants, in which he spoke unfavorably against legislation involving Southern interests. He told the men that Kansas was the battleground where the final decision was to be made, and as Southerners, they needed to be determined to "commit no wrong...and relinquish no right".[22] Baker called on the emigrants' "proverbial chivalry" and appealed to their sense of reason to rescue the South's constitutional rights and to maintain "in all vigor the institutions to which they were accustomed from their infancy".[22] A day later, Buford assembled his men in front of the Madison House in downtown Montgomery, and instructed them to abstain from consuming alcohol and to conduct themselves as gentlemen.[23] Early in the afternoon, the men marched to the Agricultural Fair Grounds, where Buford organized the group into a battalion of four companies, with Buford elected general of the entire group.[23][24] Buford proceeded to explain that the purpose of his mission was to populate Kansas with "good and true" men who would protect customary Southern rights in the territory.[23] After Buford, a number of notable dignitaries also delivered speeches, reminding the settlers that the "fate of the South depended on the success or failure of the efforts now being made to save the new territory for the South".[23]

On Sunday, the battalion attended a sermon by Reverend Isaac Taylor (I. T.) Tichenor at the local Baptist church. After the sermon, Reverend Tichenor proposed to present each member of the battalion with a Bible, a weapon he considered more powerful than the Beecher's Bibles being given to anti-slavery emigrants by some ministers in the Northern states.[23] He procured the funds needed to buy the Bibles, and turned it over to Buford, who would purchase them somewhere along the journey to Kansas. The battalion met at the Baptist church again the next day, where the church congregation offered prayer asking for "blessings of heaven" for the men, and presented Buford with a "handsome" Bible.[23]

Equipped with two large banners, one inscribed with the word "Kansas" and the other with "The Supremacy of the White Race" on the front and "Kansas, The Outpost" on the back, and silk badges with the inscription "Alabama for Kansas—North of 36°30'. Bibles—Not Rifles" on some of the men, the battalion left the church and marched on to the wharf.[25] After two final speeches from Alpheus Baker and Henry W. Hilliard, the men boarded the steamboat Messenger and headed for Mobile, prompting the booming of a cannon and cheers from the crowd of 5,000 who had gathered to see the emigrants off.[26] In Mobile, the battalion took rest for two days. There, they elected their officers: B. F. Treadwell as Colonel, Major L. F. Johnson as Quartermaster-General, Captain E. R. Bell as Adjutant-General, John W. Jones as Surgeon, and Gordon, Brown, Andrews and Jernigan as Captains.[26] On April 11, the group went to the bookstore of Messrs. McIlvaine and purchased enough Bibles for everyone in the battalion. Immediately thereafter, they went to the wharf and boarded the steamboat Florida and headed for New Orleans. In New Orleans, Buford picked up a few additional men for the expedition. The battalion was split in two for the journey up the Mississippi River—one group would travel in the steamer America and the other in the Oceana.[26]

The America and Oceana arrived in St. Louis, Missouri on April 23 and stopped there for a day. While he was in St. Louis, Buford sent a letter to Col. William Walker, provisional governor of Kansas Territory, asking if some of his men could settle on the Wyandotte Reservation.[26] On April 24, the entire battalion boarded the steamer Keystone, en route to Kansas City. Just before the steamer was about to leave port, a thief broke into Buford's trunk and stole $5,000. The money was not recovered, and local authorities believed that one of the emigrants was the thief.[27] The steamer stopped in Westport, Kansas City, where the emigrants were given equipment to prepare them for settlement in Kansas. On May 2, the men entered Kansas Territory and dispersed themselves throughout the country, looking for desirable areas to settle.[26]

Settling in Kansas[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Guelzo, Allen C. (2008), Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates that Defined America, New York: Simon & Schuster, pp. 13–19, ISBN 978-0-7432-7320-6.

- ^ Wishart, David J. (January 2004), Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, p. 670, ISBN 0-8032-4787-7.

- ^ a b c d White 1991, p. 160.

- ^ Nichols 1956, pp. 203–210.

- ^ a b c Fleming 1900, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d White 1991, p. 161.

- ^ Garner & Lodge 1906, p. 1073.

- ^ "Appeal to the South from the Kansas Emigration Society of Missouri", Advertiser and Gazette, Montgomery, Alabama, 1855.

- ^ Charleston Mercury, 1855.

- ^ a b Fleming 1900, p. 39.

- ^ a b Monaghan 1984, p. 35.

- ^ Fleming 1900, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Eufaula, Alabama Spirit of the South, November 26, 1855.

- ^ a b c d Fleming 1900, p. 40.

- ^ Alabama Journal, February 1, 1856.

- ^ a b c Neely 2007, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d Fleming 1900, p. 41.

- ^ Advertiser and State Gazette, January 13, 1856.

- ^ Worcester Spy, 1887.

- ^ Advertiser and State Gazette, March 1, 1856.

- ^ Fleming 1900, pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b c Hodgson 1876, p. 348.

- ^ a b c d e f Fleming 1900, p. 42.

- ^ Hodgson 1876, p. 349.

- ^ Fleming 1900, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c d e Fleming 1900, p. 43.

- ^ St. Louis Herald, April 26, 1856.

References[edit]

- Fleming, Walter L. (October 1900), "The Buford Expedition to Kansas", The American Historical Review, 6 (1): 38–48, doi:10.2307/1834688, JSTOR 1834688

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link). - Garner, James Wilford; Lodge, Henry Cabot (1906), The History of the United States, vol. 3, Philadelphia: J. D. Morris & Co., OCLC 2552293.

- Hodgson, Joseph (1876), The Cradle of the Confederacy: or, The times of Troup, Quitman, and Yancey: A sketch of southwestern political history from the formation of the Federal Government to A.D. 1861, Mobile, Alabama: Register Publishing Office, OCLC 248023492.

- Monaghan, Jay (1984), Civil War on the Western Border, 1854–1865, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-8126-9.

- Neely, Jeremy (2007), The Border Between Them: Violence and Reconciliation on the Kansas-Missouri Line, Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, ISBN 978-0-8262-1729-5.

- Nichols, Roy F. (September 1956), "The Kansas-Nebraska Act: A Century of Historiography", The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 43 (2): 187–212, doi:10.2307/1902683, JSTOR 1902683

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link). - White, Richard (1991), "It's Your Misfortune and None of My Own": A New History of the American West, Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-2567-5.