User:Purlspearls/Birka

| This is the sandbox page where you will draft your initial Wikipedia contribution.

If you're starting a new article, you can develop it here until it's ready to go live. If you're working on improvements to an existing article, copy only one section at a time of the article to this sandbox to work on, and be sure to use an edit summary linking to the article you copied from. Do not copy over the entire article. You can find additional instructions here. Remember to save your work regularly using the "Publish page" button. (It just means 'save'; it will still be in the sandbox.) You can add bold formatting to your additions to differentiate them from existing content. |

Birka[edit]

Birka listen (help·info) (Birca in medieval sources), on the island of Björkö (lit. "Birch Island") in present-day Sweden, was an important Viking Age trading center which handled goods from Scandinavia and Finland as well as Central and Eastern Europe and the Orient. Björkö is located in Lake Mälaren, 30 kilometers west of contemporary Stockholm, in the municipality of Ekerö.

Birka was founded around AD 750 and it flourished for more than 200 years. It was abandoned c. AD 975, around the same time Sigtuna was founded as a Christian town some 35 km to the northeast. It has been estimated that the population in Viking Age Birka was between 500 and 1000 people.

The archaeological sites of Birka and Hovgården, on the neighbouring island of Adelsö, make up an archaeological complex which illustrates the elaborate trading networks of Viking Scandinavia and their influence on the subsequent history of Europe. Generally regarded as Sweden's oldest town, Birka (along with Hovgården) has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1993. Many burial sites have been uncovered at Birka, leading to the finding of many objects including jewelry and many textile fragments. In recent years, objects from Birka have been in the under the public eye due to ongoing academic research connecting Birka to evidence of trade with the Middle East.[1]

History[edit]

Birka was founded around 750 AD as a trading port by a king or merchants trying to control trade. It is one of the earliest urban settlements in Scandinavia. Birka was the Baltic link in the Dnieper trade route through Ladoga and Novgorod to the Byzantine Empire and the Abbasid Caliphate. Birka is the site of the first known Christian congregation in Sweden, founded in 831 by Saint Ansgar.

As a trading center, Birka most likely offered furs, iron goods, and craft products, in exchange for various materials from Europe and Western Asia. Furs were obtained from the Sami people, the Finns, people in northwestern Russia, as well as from local trappers. Furs included bear, fox, marten, otter, beaver, and other species. Reindeer antlers and objects carved from reindeer antlers like combs were important items of trade. The trade of walrus teeth, amber, and honey is also documented.

Foreign goods found from the graves of Birka include glass and metalware, pottery from the Rhineland, clothing and textiles including Chinese silk, Byzantine embroidery with extremely fine gold thread, brocades with gold passementerie, and plaited cords of high quality. From the ninth century onwards coins minted at Haithabu in Northern Germany and elsewhere in Scandinavia start to appear. However, The vast majority of the coins found at Birka are silver dirhams from the Middle East while English and Carolingian coins are rare.

Rimbert and Adam of Bremen's account of Birka[edit]

Sources from Birka rely on archaeological remains. No texts survive from this area, though the written text Vita Ansgari ("The Life of Ansgar") by Rimbert (c. 865) describes the missionary work of Ansgar around 830 at Birka, and Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum (Deeds of Bishops of the Hamburg Church) by Adam of Bremen in 1075 describes the Archbishop Unni, who died at Birka in 936. Saint Ansgar's work was the first attempt to convert the people of Birka from the Norse religion to Christianity. It was unsuccessful.

Both Rimbert and Adam were German clergymen writing in Latin. There are no known Norse sources mentioning the name of the settlement, or even the settlement itself, and the original Norse name of Birka is unknown. Birca is the Latinised form given in the written sources by Rimbert and Adam; and Birka is the contemporary, unhistorical Swedish form. The Latin name is probably derived from an Old Norse word "birk" which probably means market place. Related to this was the Bjärköa law (bjärköarätt) which regulated the life of marketplaces in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Birka and similar spellings are common in Scandinavian place names leading to speculation that references to Birka, especially those by Adam of Bremen, were not about the same location.

Both publications are silent on Birka's size, layout, and appearance. Based on Rimbert's account, Birka was significant because it had a port and was the location of the regional ting. Adam only mentions the port, but otherwise, Birka seems to have been significant to him because it was the start of Ansgar's Christian mission and because Archbishop Unni was buried there.

Vita Ansgari and Gesta are sometimes ambiguous, which has caused some controversy as to whether Birka and the Björkö settlement are the same locations. Many other locations have been suggested through the years. However, Björkö is the only location that shows remains of a town of Birka's significance, which is why the vast majority of scholars regard Björkö as the location of Birka.

Birka was abandoned during the latter half of the 10th century. Based on the dating of the coins found, the city seems to have died out around 960. Roughly around the same time, the nearby settlement of Sigtuna supplanted Birka as the main trading center in the Mälaren area. The reasons for Birka's decline are disputed. A contributing factor may have been the post-glacial rebound, which lowered the water level of Mälaren changing it from an arm of the sea into a lake and cutting Birka off from the southern access to the Baltic Sea.[citation needed] The Baltic island of Gotland was also in a better strategic position for Russian-Byzantine trade and was gaining eminence as a mercantile stronghold. Historian Neil Kent has speculated that the area may have been the victim of an enemy assault.

The Varangian trade stations in Russia suffered a serious decline at roughly the same date.

Björkö Archaeological Site[edit]

The exact location of Birka was also lost during the centuries, leading to speculation from Swedish historians. In 1450, the island of Björkö was claimed to be Birka by the "Chronicle of Sweden."

In search of Birka, National Antiquarian Johan Hadorph was the first to attempt excavations on Björkö in the late 17th century.

In the late 19th century, Hjalmar Stolpe, an entomologist by education, arrived on Björkö to study fossilized insects found in amber on the island. Stolpe found very large amounts of amber, which is unusual since amber is not normally found in lake Mälaren. Stolpe speculated that the island may have been an important trading post, prompting him to conduct a series of archeological excavations between 1871 and 1895. The excavations soon indicated that a major settlement had been located on the island and eventually Stolpe spent two decades excavating the island. After Björkö came to be identified with ancient Birka, it has been assumed that the original name of Birka was simply Bierkø (sometimes spelled Bjärkö), an earlier form of Björkö.

A significant collection of textiles fragments were retrieved during excavations, mostly from chamber graves. Agnes Geijer published the most detailed analysis of this collection in 1938, although her study was based upon only around 5% of the 4800 textile fragments preserved from the site. The collection represents a usual variety of different types of textiles showing high quality textiles manufactured by different techniques like tabby and twill. Mostly made from wool and flax, the quality of the textiles studied by Geijer ranged from very coarse to fine fabrics with high thread counts that required complicated techniques to create. The variety of materials and techniques to make the tablet woven textiles led Geijer to theorize that some of the textiles were imported. Geijer also found remains of the three-end twill textile that has not been found anywhere else in Northern Europe.[2] Geijer theorized that some of the fragments came from the East, possibly China, due the use of gold and silver wire as well as silk.[3]

Ownership of Björkö is today mainly in private hands and is used for farming. The settlement site, however, is an archaeological site, and a museum has been built nearby for an exhibition of finds (mostly replicas), models and reconstructions. It is a popular site to visit during the summer times. The complete collection of archaeological finds from the excavations on Björkö are held by The Swedish History Museum in Stockholm, and many of the artifacts are on display there.

The archaeological remains are located in the north part of Björkö and span an area of about 7 hectares (17 acres). The remains are both burial-sites and buildings, and in the south part of this area, there is also a hill fort called "Borgen" ("The Fortress"). The construction technique of the buildings is still unknown, but the main material was wood. An adjacent island holds the remains of Hovgården, an estate that housed the King's retinue during visits.

Approximately 700 people lived at Birka when it was at its largest, and about 3,000 graves have been found. Its administrative center was supposedly located outside of the settlement itself, on the nearby island of Adelsö.

The most recent large excavation was undertaken between 1990 and 1995 in a region of dark earth, believed to be the site of the main settlement.

Björkö Objects[edit]

"Allah" Textile Controversy[edit]

In 2017, Annika Larsson, a textile researcher, claimed in a press release by Uppsala University to have discovered a textile among the finds from Birka that bore the Arabic words "Allah" and "Ali".[4][5] She theorized that some of the Viking people could have converted to Islam, leading to a media frenzy.[6] Dr. Stephennie Mulder, a professor of Islamic art at the University of Texas at Austin, replied to Larsson’s findings in a Twitter thread.[7] Mulder argued that the textile could not read Allah because the dating of the object was from the 10th century and the style of writing, Square Kufic, is not seen until the 15th century. Larsson proposed extensions to the tablet weaving that expanded beyond the original drawing by Agnes Geijer in 1938.[8] Textile specialist, Carolyn Priest-Dorman, argued that the expansions are improbable because the fragment has finished edges called selvages and the band would have cut weft threads if the fragment had been narrowed at some point.[9] Larsson’s drawings were based on her own ideas and not on any proof of what an expanded design would look like or if an expansion even existed. The backlash after Mulder and other historians' criticism led to the object listing at Uppsala University website to include the skepticism of Larsson’s research.[4]

"Allah" Ring Controversy[edit]

A ring was found during the archeological excavations at Birka between 1872 and 1895, when archeologist Hjalmar Stolpe discovered it in a 9th century Viking woman's burial. It is made of high-quality silver alloy and is set with a pink-violet oval glass.[10] The ring, preserved at the Swedish history museum, became known as the "Allah ring" because of the pseudo-Kufic inscription found on the ring’s glass that resembles the word Allah (Arabic: الله). While other rings were found at the Birka excavations, the "Allah ring" was the only one that had this type of inscription. The Arabic historical linguist Marijn van Puten argued that the inscription on the ring was an example of pseudo-Kufic and that it has no meaning in Arabic.[11] Nevertheless, other analysts extrapolated that the pseudo-Kufic engraving was indeed Arabic and that this was sufficient evidence to directly link Vikings to Islamic civilization.[12] In her Twitter thread on the "Allah” textile, Stephennie Mulder drew on the work of van Putten to argue that like the textile, the ring had been similarly understood. However, she acknowledged that the Arabic language—found on the ring and other objects from Birka—was appreciated by the Vikings as a sign of social status.[13] The inscription could suggest that the ring owner might have been one of the Viking elites who were in contact with the Islamic world via trade or travel.[14]

Dragonhead[edit]

The Birka dragonhead is a 45mm long decorative object made from a tin alloy. Sven Kalmring and Lena Holmquist maintain that the dragonhead was cast from a soapstone mold due to the presence of casting burs on the object and the fact that similar casting molds of dragons have been found in Birka. Stylistically similar dragonheads have been discovered around the Baltic, and scholars like Anne-Sofie Gräslund believe they likely functioned as dress pins.[15]

Wearable Accessories[edit]

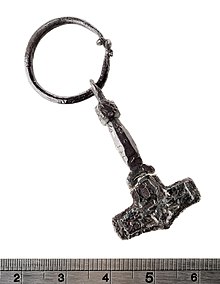

10 small silver crosses were found in graves at Birka.[16] Missionaries, brought by Rimbert and others, lead to some converts to Christianity.[16] 27 graves contained small pendants of Thor’s hammer from around the 10th century. Both traditional Viking religious beliefs and Christianity were present at Birka.[17]

Many Birka grave excavations produced a number of funerary findings unique to the deceased and the region of the grave. In the excavation of grave Bj 463, a small copper alloy brooch with animal motifs was found alongside the skeletal remains of a young girl from Birka, and similar ones appeared in other excavations around Birka.[18]

The brooch is understood to be typically related to female burials and also female jewelry of the Viking period. The surrounding fragments of textiles attached to these brooches, scattered around various graves across Sweden, also give an understanding of what the typical womenswear of the Viking age may have been in the 9th and 10th centuries.[19]

Dirham Coins[edit]

Dirham coins have been located all around Scandinavian countries and suggest strong trade relations existed between the medieval Middle East and Northern Europe.[20] A dirham coin was found in the excavation of grave sites in Birka, with Arabic writing and an absence of imagery that would date the coin sometime after the 7th century.[21] Other writing on the coin indicates the location of the mint as well as the names of a caliph and an Amir, which place the coin’s origins in al-Shah, modern day Tashkent inUzbekistan. The coin’s inscription in Arabic translates into English:

There is no deity but Allah alone he has no equal For God Muhammad is the messenger of God.[22]

Birka Burial Sites[edit]

Over 3,000 grave sites are located in Birka, including both cremations and inhumations in coffins or chamber graves.[23][24] Skeletal analysis and the presence of gender-specific jewelry and objects in graves has shown that the majority of the deceased are female. Scholar Nancy L. Wicker suggests that the disproportionate number of female graves is due to the fact that female grave goods are easily identifiable, but male graves without objects are difficult to identify.[23]

Many graves contain objects such as coins, glass, and textiles that originated in foreign countries as far as the Middle East and Eastern Asia. According to Nancy L. Wicker, these objects were either imported to Birka as luxury trade goods, or they belonged to foreign individuals who were buried at Birka.[23]

Grave Bj 582: Female Warrior[edit]

Grave Bj 463: Young Girl[edit]

Grave Bj 463 contained the skeleton of a girl from the mid-10th century. She was buried in a coffin with grave goods associated with high-status women, including a round brooch, glass beads, and a needle case.[18] By the condition of her teeth, she was 5-6 years old at the time of her death, and further analysis determined that her diet was similar to that of male warriors instead of a typical child’s diet.[18][25] Scholar Marianne Hem Eriksen maintains that this girl is an unusual case of a high-status child burial, as children were seldom buried with identifiable grave goods.[25]

References[edit]

- ^ Geijer, Agnes (1979). A history of textile art. London: Pasold Research Fund in association with Sotheby Parke Bernet. p. 245. ISBN 0-85667-055-3. OCLC 5871922.

- ^ Geijer, Agnes (1979). A history of textile art. London: Pasold Research Fund in association with Sotheby Parke Bernet. p. 71. ISBN 0-85667-055-3. OCLC 5871922.

- ^ Geijer, Agnes (1979). A history of textile art. London: Pasold Research Fund in association with Sotheby Parke Bernet. pp. 220–221. ISBN 0-85667-055-3. OCLC 5871922.

- ^ a b Naylor, David. "Exhibition: Viking Age patterns may be Kufic script - Uppsala University, Sweden". www.uu.se. Retrieved 2021-11-10.

- ^ "Viking Age Script Deciphered - Mentions 'Allah' and 'Ali'". 2017-10-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Anderson, Christina (2017-10-14). "'Allah' Is Found on Viking Funeral Clothes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-11-10.

- ^ "https://twitter.com/stephenniem/status/919897406031978496". Twitter. Retrieved 2021-11-10.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Samuel, Sigal (2017-10-17). "Did Viking Couture Really Feature the Word 'Allah'?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2021-11-10.

- ^ Priest-dorman, Carolyn (2017-10-12). "A String Geek's Stash: Viking Age Tablet Weaving: Kufic or Not?". A String Geek's Stash. Retrieved 2021-11-28.

- ^ "Analysis and interpretation of a unique Arabic finger ring from the Viking Age town of Birka, Sweden". doi:10.1002/sca.21189.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "https://twitter.com/phdnix/status/920584737168723968". Twitter. Retrieved 2021-11-29.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ "Analysis and interpretation of a unique Arabic finger ring from the Viking Age town of Birka, Sweden". doi:10.1002/sca.21189.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "https://twitter.com/stephenniem/status/919897406031978496". Twitter. Retrieved 2021-11-29.

{{cite web}}: External link in|title= - ^ Fernstål, Lotta (2008-01-01). "A Bit Arabic. Pseudo-Arabic Inscriptions on Viking Age Weights in Sweden and Expressions of Self-image". Current Swedish Archaeology.

- ^ Kalmring, Sven; Holmquist, Lena (2018-06). "'The gleaming mane of the serpent': the Birka dragonhead from Black Earth Harbour". Antiquity. 92 (363): 742–757. doi:10.15184/aqy.2018.50. ISSN 0003-598X.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Geijer, Agnes (1979). A history of textile art. London: Pasold Research Fund in association with Sotheby Parke Bernet. p. 22. ISBN 0-85667-055-3. OCLC 5871922.

- ^ Geijer, Agnes (1979). A history of textile art. London: Pasold Research Fund in association with Sotheby Parke Bernet. p. 24. ISBN 0-85667-055-3. OCLC 5871922.

- ^ a b c Herausgeber., Hem Eriksen, Marianne. VIKING WORLDS : things, spaces and movement. ISBN 978-1-78925-210-1. OCLC 1096352449.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jesch, Judith (1991). Women in the Viking Age. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85115-360-5.

- ^ Gruszczyński, Jacek (2019-01-10). Viking Silver, Hoards and Containers. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY : Routledge, 2019. | Series: Routledge archaeologies of the Viking world: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-24365-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ author., Deliyannis, Deborah Mauskopf, 1966-. Fifty early medieval things : materials of culture in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. ISBN 978-1-5017-2589-0. OCLC 1031955948.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Deliyannis, Deborah Mauskopf (2019). Fifty early Medieval things : materials of culture in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. Hendrik W. Dey, Paolo Squatriti. Ithaca. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-5017-3028-3. OCLC 1033548555.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c WICKER, NANCY L. (2012). "Christianization, Female Infanticide, and the Abundance of Female Burials at Viking Age Birka in Sweden". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 21 (2): 245–262. ISSN 1043-4070.

- ^ Hedenstierna-Jonson, Charlotte; Kjellström, Anna; Zachrisson, Torun; Krzewińska, Maja; Sobrado, Veronica; Price, Neil; Günther, Torsten; Jakobsson, Mattias; Götherström, Anders; Storå, Jan (2017-09-08). "A female Viking warrior confirmed by genomics". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 164 (4): 853–860. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23308. ISSN 0002-9483.

- ^ a b Eriksen, Marianne Hem (2017-05-27). "Don't all mothers love their children? Deposited infants as animate objects in the Scandinavian Iron Age". World Archaeology. 49 (3): 338–356. doi:10.1080/00438243.2017.1340189. ISSN 0043-8243.