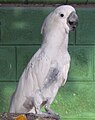

White cockatoo

| White cockatoo | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Pairi Daiza, Belgium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Cacatuidae |

| Genus: | Cacatua |

| Subgenus: | Cacatua |

| Species: | C. alba

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cacatua alba Müller, 1776

| |

The white cockatoo (Cacatua alba), also known as the umbrella cockatoo, is a medium-sized all-white cockatoo endemic to tropical rainforest on islands of Indonesia. When surprised, it extends a large and striking head crest, which has a semicircular shape (similar to an umbrella, hence the alternative name). The undersides of the wings and tail have a pale yellow or lemon color which flashes when they fly. It is similar to other species of white cockatoo such as yellow-crested cockatoo, sulphur-crested cockatoo, and salmon-crested cockatoo, all of which have yellow, orange or pink crest feathers instead of white.

Taxonomy

The white cockatoo was first described in 1776 by German zoologist Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller. Its species name alba is a feminine form of the Latin adjective albus for "white". It lies in the subgenus Cacatua within the genus Cacatua. The term "white cockatoo" has also been applied as a group term to members of the subgenus Cacatua, the genus Cacatua as well as larger groups including Major Mitchell's cockatoo and the galah cockatoo.

While psittaciform parrots and cockatoos have many common anatomical attributes like zygodactyl feet and hooked bills, the cockatoos and parrots diverged from the ancestral parrots as separate lineages as early as 45 MYA (fossil record) or 66 MYA (molecular analysis) (Wright 2008) during the period when Australia, South America and Antarctica were breaking away from the super-continent Gondwanaland where the ancestral parrots were believed to have evolved.

Although historically white cockatoos and related species have been referred to as "white parrots", taxonomically they are not considered to be true parrots.

Description

The white cockatoo is around 46 cm (18 in) long, and weighs about 400 g (14 oz) for small females and up to 800 g (28 oz) for big males. The male white cockatoo usually has a broader head and a bigger beak than the female. They have brown or black eyes and a dark grey beak. When mature some female white cockatoos can have reddish/brown irises, while the irises of the adult male are dark brown or black.

The feathers of the white cockatoo are mostly white. However, both upper and lower surfaces of the inner half of the trailing edge of the large wing feathers are a yellow color. The yellow color on the underside of the wings is most notable because the yellow portion of the upper surface of the feather is covered by the white of the feather immediately medial (nearer to the body) and above. Similarly, areas of larger tail feathers that are covered by other tail feathers – and the innermost covered areas of the larger crest feathers – are yellow. Short white feathers grow from and closely cover the upper legs. The feathers of this species and others create a powder similar to talcum powder that easily transfers to clothing.

In common with other cockatoos and parrots, the white cockatoo has zygodactyl feet with two toes facing forward and two facing backward, which enable it to grasp objects with one foot while standing on the other, for feeding and manipulation.

Whilst the maximum lifespan of the white cockatoo is poorly documented; a few zoos report that they live 40–60 years in captivity. Anecdotal reports suggest it can live longer. Lifespan in the wild is unknown, but believed to be as much as ten years less.

Distribution and habitat

Cacatua alba is endemic to lowland tropical rainforest on the islands of Halmahera, Bacan, Ternate, Tidore, Kasiruta and Mandioli (Bacan group) in North Maluku, Indonesia. Records from Obi and Bisa (Obi group) are thought to be introductions. It occurs in primary, logged, and secondary forests below 900m. It also occurs in mangroves, plantations including coconut and agricultural land. Cacatua alba is endemic to the islands of Halmahera, Bacan, Ternate, Tidore, Kasiruta and Mandiole in North Maluku, Indonesia. Records from Obi and Bisa are thought to reflect introductions, and an introduced population breeds locally in Taiwan. It remains locally common: in 1991-1992, the population was estimated at 42,545-183,129 birds (Lambert 1993), although this may be an underestimate as it was largely based on surveys from Bacan and not Halmahera where the species may have been commoner. Recent observations indicate that rapid declines are on-going, and are predicted to increase in the future (Vetter 2009). CITES data show significant harvest rates for the cage bird trade during the early 1990s.; annual harvests have declined in actual terms and as a proportion of the remaining population in recent years, but illegal trade continues and is likely to have been underestimated (S. Metz in litt. 2013).

Behavior

Breeding

Like all cockatoos, the white cockatoo nests in hollows of large trees. Its eggs are white and there are usually two in a clutch. During the incubation period – about 28 days – both the female and male incubate the eggs. The larger chick becomes dominant over the smaller chick and takes more of the food. The chicks leave the nest about 84 days after hatching.[2] and are independent in 15–18 weeks.

Juveniles reach sexual maturity in 3–4 years. As part of the courtship behavior, the male ruffles his feathers, spreads his tail feathers, extends his wings, and erects his crest. He then bounces about. Initially, the female ignores or avoids him, but – provided he meets her approval – will eventually allow him to approach her. If his efforts are successful and he is accepted, the pair will be seen preening each other's head and scratching each other around the tail. These actions serve to strengthen their pair bond. Eventually, the male mounts the female and performs the actual act of mating by joining of the cloacae. For bonded pairs, this mating ritual is much shorter and the female may even approach the male. Once they are ready for nesting, breeding pairs separate from their groups and search for a suitable nest cavity (usually in trees).

Feeding

In the wild, white cockatoos feed on berries, seeds, nuts, fruit and roots. When nesting, they include insects and insect larvae. In their natural habitat, umbrella cockatoos typically feed on various seeds, nuts and fruits, such as papaya, durian, langsat and rambutan. As they also feed on corn growing in fields, they do considerable damage and are therefore considered crop pests by farmers. (BirdLife International, 2001) They also eat large insects, such as crickets (order Orthoptera) and small lizards such as skinks. Captive birds are usually provided a parrot mix containing various seeds, nuts and dried fruits and vegetables. Additionally, they need to be offered lots of fresh vegetables, fruits and branches (with leaves) for chewing and entertainment.

Conservation status

The white cockatoo is considered Endangered by the IUCN.[1] Its numbers in the wild have declined owing to capture for the cage bird trade and habitat loss.[3] It is listed in appendix II of the CITES list which gives it protection by restricting export and import of wild-caught birds. BirdLife International indicates that catch quotas issued by the Indonesian government were 'exceeded by up to 18 times in some localities' in 1991, with at least 6,600 umbrella cockatoos being taken from the wild by trappers - although fewer birds have been taken from the wild in recent years, both in numerical terms and when taken as a proportion of the entire population.[3] RSPCA supported surveys by the Indonesian NGO ProFauna suggest that significant levels of trade in wild-caught white cockatoos still occur, with 200+ taken from the wild in north Halmahera in 2007.[4] Approximately 40% of the parrots (white cockatoo, chattering lory, violet-necked lory and eclectus parrot) caught in Halmahera are smuggled to the Philippines, while approximately 60% go to the domestic Indonesian trade, especially via bird markets in Surabaya and Jakarta.[4]

The illegal trade of protected parrots violates Indonesian Act Number 5, 1990 (a wildlife law concerning Natural Resources and the Ecosystems Conservations).[5]

Aviculture

White cockatoos are kept as pets because they can be very affectionate, bond closely with people and are valued for their beauty. They are often called "velcro birds" because they like to cuddle with people, especially their owners, or primary care-taker. Anyone not used to cockatoo behavior may find this cuddling behavior odd, as most parrots do not cuddle like the umbrella cockatoo. Although capable of imitating basic human speech, they are not considered the most able speakers among parrots. They are often used in live animal acts in zoos and amusement parks because they are naturally acrobatic and easily trained, because of their highly social nature and high level of intelligence.

Cockatoos are also noisier than many parrots. They can become very bonded (or dependent) on their human companion and this combined with their long life and often misunderstood behaviors can lead to behavior issues. They have very strong beaks which can be easily used to crack walnuts or maim fingers with ease. They also have a "fight or flight" flock mentality, and generally prefer to fly away from danger. In a cage, with no escape path, they can be subjected to stress which often leads to feather picking (as with many pet birds). Like other cockatoos, White cockatoos can learn a large number of words, and are able to construct simple sentences with the words they learn.

Pet white cockatoos may raise their crests upon training, or when something catches their interest such as a new toy or person.

Health issues with captive birds are common since many people do not provide a proper diet for cockatoos. Seeds provide little nutrition (they are mostly fat) and is considered similar to a person living on junk food. Assorted fresh fruits and vegetables and properly created pellets available at many good pet stores are more appropriate. A sick bird naturally will try to hide its health issues. In the wild, it has been observed that a flock will force out an unhealthy bird for fear of attracting predators. An often cited rule of thumb among avian enthusiasts and veterinarians is: "If the bird looks sick, it is likely to be very, very sick – possibly near death". Qualified avian veterinary care is required, both for prevention of disease, and for care in the event of a major illness or trauma.

Signs of illness in a cockatoo can include runny eyes, sluggish behavior, unusually colored droppings (esp indicating blood in the digestive tract), sleeping more than normal, droopy wings, tail bobbing when sleeping (indicating difficulty in breathing), sleeping on the bottom of the cage (birds naturally want to be high on a perch), sudden change in or unusual behavior, feather plucking, biting themselves, sudden weight loss or gain, and a drop in appetite, among other symptoms.

History

They were quite popular in China during the Tang dynasty, a fact which in turn influenced the depictions of Guan Yin with a white parrot. The Fourth Crusade was also sealed between Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and the Sultan of Babylon in 1229 with a gift of a white cockatoo.

Gallery

-

Crest feathers.

-

More Crest feathers.

-

Even more.

-

With crest retracted.

-

White cockatoo chicks. (hand reared)

-

White cockatoo with a minor plucking problem.

-

Cacatua alba - First Born - Fresh out of shell and not even dry yet.

-

Cacatua alba - 3 Weeks - Eyes first starting to open. Still has egg tooth. Full crop after being hand-fed.

-

Cacatua alba - 6 Weeks - Pin feathers developing. Egg tooth gone.

References

- ^ a b Template:IUCN

- ^ Alderton, David (2003). The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Caged and Aviary Birds. London, England: Hermes House. p. 204. ISBN 1-84309-164-X.

- ^ a b "BirdLife International (2011) Species factsheet: Cacatua alba". Birdlife International. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ a b ProFauna Indonesia (2008). Pirated Parrots Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- ^ "Indonesia Ministry of Forestry 1990".

Further reading

- Handbook of the Birds of the World – Volume 4 ("Cacatuidae"): Sandgrouse to Cuckoos. del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J. Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-22-9.

External links

- The Indonesian parrot Project: conservation of cockatoos and other Indonesian parrots

- BirdLife Species Factsheet

- MyToos information for people buying a cockatoo

- ProFauna an organization for the protection of animals in Indonesia