William M. Tweed: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 71.41.38.234 to last version by 71.195.95.192 (HG) |

|||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

Tweed was accused of defrauding the city by having contractors present excessive bills for work performed—typically ranging from 30 to 90 percent more than the project actually cost. The extra charges were said to have been divided among Tweed, his subordinates and the contractors. The most excessive overcharging came in the form of the [[Tweed Courthouse]], which cost the city $13 million to construct (the actual cost for the courthouse was about $3 million), leaving about $10 million for the pockets of Tweed and others.<ref>The Americans: Reconstruction to the 21st Century: California Teacher's Edition (Evanston: McDougall Littell Inc., 2006), 269; see also http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=211 for more alarming figures on the excesses of the Tweed political machine</ref> |

Tweed was accused of defrauding the city by having contractors present excessive bills for work performed—typically ranging from 30 to 90 percent more than the project actually cost. The extra charges were said to have been divided among Tweed, his subordinates and the contractors. The most excessive overcharging came in the form of the [[Tweed Courthouse]], which cost the city $13 million to construct (the actual cost for the courthouse was about $3 million), leaving about $10 million for the pockets of Tweed and others.<ref>The Americans: Reconstruction to the 21st Century: California Teacher's Edition (Evanston: McDougall Littell Inc., 2006), 269; see also http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=211 for more alarming figures on the excesses of the Tweed political machine</ref> |

||

Tweed's downfall came when he refused to authorize the Orange Parade, an annual Protestant celebration. City Sheriff James O'Brien, whose support for Tweed had fluctuated during Tammany's "reign", gave ''[[The New York Times]]'' evidence of [[embezzlement]] in light of the Protestant-Catholic riot that ensued on parade day. The newspaper was reportedly offered $5 million to not publish the evidence. In a subsequent interview, Tweed's only reply was, "Well, what are you going to do about it?"{{Fact|date=May 2008}} Accounts in ''The New York Times'' and political cartoons drawn by [[Thomas Nast]] and published in ''[[Harper's Weekly]]'' resulted in the election of numerous opposition candidates in 1871. Regarding Nast's cartoons, Tweed reportedly said, "Stop them damned pictures. I don't care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them |

Tweed's downfall came when he refused to authorize the Orange Parade, an annual Protestant celebration. City Sheriff James O'Brien, whose support for Tweed had fluctuated during Tammany's "reign", gave ''[[The New York Times]]'' evidence of [[embezzlement]] in light of the Protestant-Catholic riot that ensued on parade day. The newspaper was reportedly offered $5 million to not publish the evidence. In a subsequent interview, Tweed's only reply was, "Well, what are you going to do about it?"{{Fact|date=May 2008}} Accounts in ''The New York Times'' and political cartoons drawn by [[Thomas Nast]] and published in ''[[Harper's Weekly]]'' resulted in the election of numerous opposition candidates in 1871. Regarding Nast's cartoons, Tweed reportedly said, "Stop them damned pictures. I don't care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them Fucking |

||

pictures!"<ref>[http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~bjackson/lazio.html lazio<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

=== Imprisonment, escape, and death === |

=== Imprisonment, escape, and death === |

||

Revision as of 19:49, 10 December 2008

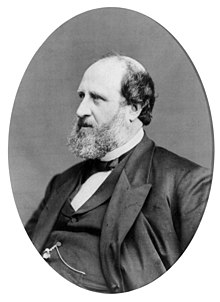

William Marcy Tweed | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York's 5th district | |

| In office March 4, 1853 – March 3, 1855 | |

| Preceded by | George Briggs |

| Succeeded by | Thomas R. Whitney |

| Personal details | |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Profession | Politician |

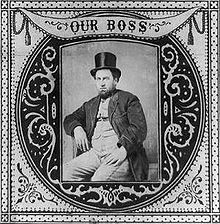

William M. Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878), sometimes informally called "Boss" Tweed, was an American politician who was convicted for stealing between 40 million and 200 million dollars[1] from New York City taxpayers through political corruption. Tweed was head of Tammany Hall, the Democratic Party political machine that played a major role in the politics of 19th century New York. He died in prison.

Biography

William Magear Tweed [2] was born April 3, 1823, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Son to a chair-maker of Scottish-Irish descent, Tweed made his entrance into politics when he organized the Americus Fire Company No. 6 (also known as the "big six") as a volunteer fireman. Tweed was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1852, the New York City Board of Advisors in 1856, and the New York State Senate in 1867. Financiers Jay Gould and Big Jim Fisk made Tweed a director of the Erie Railroad, and Tweed in turn arranged favorable legislation for them. Tweed and Gould became the subjects of political cartoons by Thomas Nast in 1869.

Scandal

A Harper's Weekly cartoon depicts Tweed as a police officer saying to two boys, "If all the people want is to have somebody arrested, I'll have you plunderers convicted. You will be allowed to escape, nobody will be hurt, and then Tilden will go to the White House and I to Albany as Governor."

In April 1870 Tweed secured the passage of a city charter putting the control of the city into the hands of mayor, the comptroller, and the commissioners of parks and public works. He then allowed contractors and others to submit invoices for inflated amounts or for work that was not done. The total amount of money stolen was never known, but has been estimated from $75 million to $200 million according to The American Pageant.[citation needed] Over a period of two years and eight months, while he had over 1,000 workers at his command, New York City's debts increased from $36 million in 1868 to about $136 million by 1870, with few costs or expenditures to show for the debt.

Tweed was accused of defrauding the city by having contractors present excessive bills for work performed—typically ranging from 30 to 90 percent more than the project actually cost. The extra charges were said to have been divided among Tweed, his subordinates and the contractors. The most excessive overcharging came in the form of the Tweed Courthouse, which cost the city $13 million to construct (the actual cost for the courthouse was about $3 million), leaving about $10 million for the pockets of Tweed and others.[3]

Tweed's downfall came when he refused to authorize the Orange Parade, an annual Protestant celebration. City Sheriff James O'Brien, whose support for Tweed had fluctuated during Tammany's "reign", gave The New York Times evidence of embezzlement in light of the Protestant-Catholic riot that ensued on parade day. The newspaper was reportedly offered $5 million to not publish the evidence. In a subsequent interview, Tweed's only reply was, "Well, what are you going to do about it?"[citation needed] Accounts in The New York Times and political cartoons drawn by Thomas Nast and published in Harper's Weekly resulted in the election of numerous opposition candidates in 1871. Regarding Nast's cartoons, Tweed reportedly said, "Stop them damned pictures. I don't care so much what the papers say about me. My constituents don't know how to read, but they can't help seeing them Fucking pictures!"[4]

Imprisonment, escape, and death

In October 1872, Tweed was arraigned and held on $8 million bail. The efforts of political reformers William H. Wickham (1875 New York City mayor) and Samuel J. Tilden (later the 1876 Democratic presidential nominee) resulted in Tweed's trial and conviction in 1873. Tweed was given a 12-year prison sentence, which was reduced by a higher court and he served one year. He was then re-arrested on civil charges, sued by New York State for $6 million and held in debtor's prison until he could post $3 million as bail. On December 4, 1875, Tweed escaped and fled to Spain. The U.S. government discovered his eventual destination of Spain and arranged for his arrest as soon as he reached the Spanish border. He was delivered to authorities in New York City on November 23, 1876, and was returned to prison.[citation needed]

Tweed died in the Ludlow Street Jail on April 12, 1878 from severe pneumonia. He was buried in the Brooklyn Green-Wood Cemetery.[5]

In studies of Tweed and the Tammany Hall organization, historians have emphasized the thievery and conspiratorial nature of Boss Tweed along the Upper West Side, and securing land for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Certain aspects of Tammany Hall's activities (aid to the sick and unemployed, advocacy for tenants and workers) foreshadowed later developments in the U.S. labor movement and Social Security.

Portrayals in popular culture

- Boss Tweed was portrayed by Jim Broadbent in the 2002 film Gangs of New York.

- Tweed, portrayed as villainous and vindictive, was mentioned in chapter 14 of Neal Shusterman's young adult novel Downsiders.

- In the Elseworlds miniseries Green Lantern: Evil's Might, Tweed and Tammany Hall are featured as two of the main villains. This depiction of Tweed even goes as far as to mention Thomas Nast's political cartoons.

- In the 1977 science-fiction novel "The Ophiuchi Hotline" by John Varley, a crooked politician in the human-settled Moon of the 27th century takes up the name "Boss Tweed" in deliberate emulation of the 19th Century politician, and even names his Lunar headquarters "Tammany Hall".

- The role of Boss Tweed was originated by Noah Beery, Sr. in the 1945 original Broadway production of "Up In Central Park".

- Tweed has a cameo appearance of sorts in the novel Inferno by Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle. In Bolgia 5 of the Malebolge, demons are seen pulling Tweed out of the lake of boiling pitch and torturing him.

- Bill Tweed appears in Pete Hamill's novel, Forever, not as a villain, but a gay man who defended the rights of minorities and helped those in need.

- Tweed doesn't appear in The Waterworks (novel) but his role in the criminal case is a very important one. His name is often mentioned.

- A mouse version of Boss Tweed appears in An American Tail. Called "Honest John," he is a scheming politician who stays in power by the election fraud and ghost votes the immigrant mice.

References

- ^ "Boss Tweed", Gotham Gazette, New York, 4 July 2005.

- ^ Michael Pollak, "Hendrix Meets the Monkees," New York Times, 9 July 2006.

- ^ The Americans: Reconstruction to the 21st Century: California Teacher's Edition (Evanston: McDougall Littell Inc., 2006), 269; see also http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=211 for more alarming figures on the excesses of the Tweed political machine

- ^ lazio

- ^ Ackerman 2005:28

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. Boss Tweed. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2005.

- "Boss Tweed", Gotham Gazette, New York, 4 July 2005.

- Sante, Luc. Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York. Farrar, Straus, & Giroux, 2003.

The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. High Beam Encyclopedia. 22, November 2008.

<http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1E1-Tweed-Wi.html>

Further reading

- Lynch, Denis T. Boss Tweed The story of a grim generation. Blue Ribbon Books NY first print 1927 copyright Boni & Liveright Inc.

- Mandelbaum, Seymour J. Boss Tweed's New York, 1965. ISBN 0471566527

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. Boss Tweed: The Rise and Fall of the Corrupt Politician Who Conceived the Soul of New York, 2006.

- Hershkowitz, Leo. Tweed's New York: Another Look, 1977.

External links

- United States Congress. "William M. Tweed (id: T000440)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Tammany Hall Links

- Articles needing cleanup from December 2007

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from December 2007

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from December 2007

- Political bosses

- Political corruption

- Leaders of Tammany Hall

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from New York

- New York State Senators

- American criminals

- Criminals of New York City

- American fraudsters

- Political scandals in the United States

- Scots-Irish Americans

- Burials at Green-Wood Cemetery

- 1823 births

- 1878 deaths

- American people who died in prison custody

- Prisoners who died in New York detention

- American escapees

- Escapees from New York detention