Woodstock, Vermont

Woodstock, Vermont | |

|---|---|

(2008) | |

Location in Windsor County and the state of Vermont. | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Vermont |

| County | Windsor |

| Chartered | 1761 |

| Area | |

• Total | 44.6 sq mi (115.6 km2) |

| • Land | 44.4 sq mi (114.9 km2) |

| • Water | 0.3 sq mi (0.7 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,132 ft (345 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

• Total | 3,048 |

| • Density | 68/sq mi (26/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 05091 |

| Area code | 802 |

| FIPS code | 50-85975[1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1462272[2] |

| Website | www |

Woodstock is the shire town and county seat[3][4] of Windsor County, Vermont, in the United States. As of the 2010 census, the town population was 3,048.[5] It includes the villages of South Woodstock, Taftsville, and Woodstock.

History

Chartered by New Hampshire Governor Benning Wentworth on July 10, 1761, the town was a New Hampshire grant to David Page and 61 others. It was named after Woodstock in Oxfordshire, England, as a homage to both Blenheim Palace and its owner, George Spencer, 4th Duke of Marlborough. The town was first settled in 1768 by James Sanderson and his family.[6] In 1776, Major Joab Hoisington built a gristmill, followed by a sawmill, on the south branch of the Ottauquechee River.[7] The town was incorporated in 1837.[8]

Although the Revolution slowed settlement, Woodstock developed rapidly once the war ended in 1783. The Vermont General Assembly met here in 1807 before moving the next year to the new capital at Montpelier. Waterfalls in the Ottauquechee River provided water power to operate mills. Factories made scythes and axes, carding machines, and woolens. There was a machine shop and gunsmith shop. Manufacturers also produced furniture, wooden wares, window sashes and blinds. Carriages, horse harnesses, saddles, luggage trunks and leather goods were also manufactured. By 1859, the population was 3,041.[7] The Woodstock Railroad opened to White River Junction on September 29, 1875, carrying freight and tourists. The Woodstock Inn opened in 1892.[9]

The Industrial Revolution helped the town grow prosperous. The economy is now largely driven by tourism. Woodstock has the 20th highest per-capita income of Vermont towns as reported by the United States Census, and a high percentage of homes owned by non-residents. The town's central square, called the Green, is bordered by restored late Georgian, Federal Style, and Greek Revival houses. The cost of real estate in the district adjoining the Green is among the highest in the state.[citation needed] The seasonal presence of wealthy second-home owners from cities such as Boston and New York has contributed to the town's economic vitality and livelihood, while at the same time diminished its accessibility to native Vermonters.[citation needed]

The town maintains a free (paid for through taxation) community wi-fi internet service that covers most of the village of Woodstock, dubbed "Wireless Woodstock".[10]

Layout and design

In his City Life: Urban Expectations in a New World, Canadian author and architect Witold Rybczynski extensively analyzes the layout of the town and the informal and unwritten rules which determined it. According to Rybczynski:

The overall plan seems to have been dictated by the site: a narrow, flat valley hemmed in by the sweeping curve of the Ottauqueechee River on one side and a small creek on the other. The green was laid out lengthwise on the narrow peninsula between the river and the creek, allowing for many plots to have rear gardens running down to the riverbank. ...

The builders of Woodstock were aware that important buildings needed important sites. The Episcopalian church is at the head of the green, the Methodist farther down, and the Congregationalist church artfully closes the vista of Pleasant Street where it dead-ends into Elm Street. ... The pride of place, on the green, is shared by private homes on one side, and the courthouse and the Eagle Hotel on the other. Stores, banks, the post office and other businesses are located on two streets adjacent to but not actually on the green. This is a subtle sort of urban design, but it is design, design that proceeds not from a predetermined master plan, but from the process of building itself. A rough framework is established, with individual builders adapting as they come along. If Parisian planning in the grand manner can be likened to carefully scored symphonic music, the New England town is like ... very restrained jazz. ... [L]ike jazz, it involves improvisation, and as in jazz, this does not mean that the result is accidental or that there are no rules.[11]

The author goes on to explicate some of the informal rules, such as that buildings stand close to the sidewalk, in the case of businesses, or ten to fourteen feet behind for homes; that plots are generally deep and narrow, keeping street frontages roughly equivalent; commercial buildings stand side by side, with only important buildings with a public function – the library or courthouse, for instance – being free-standing objects. Rybczynsk points out that there is no zoning in Woodstock, and "buildings with different functions sat – and still sit today – side by side on the same streets", with practical exceptions such as the slaughterhouse and the gasworks.[11]

The Rockefellers have had an enormous impact on the overall character of the town as it exists today. They helped preserve the 19th century architecture and the rural feel.[citation needed] They built the Woodstock Inn, a center point for the town. Laurance and Mary French Rockefeller also had the village's power lines buried underground. To protect their ridgeline views, the town adopted an ordinance creating a Scenic Ridgeline District in order to protect the aesthetics and the views of the town. It was updated in 2007.[12]

Woodstock was named "The Prettiest Small Town in America" by the Ladies Home Journal magazine,[13] and in 2011, North and South Park Street and one block of Elm Street won an award for great streetscape by the American Planning Association's "Great Places in America" program. APA looks at street form and composition, street character and personality and the overall street environment and sustainable practices.

-

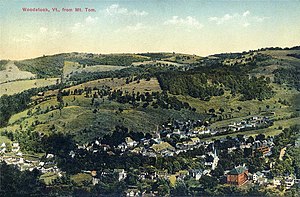

Town center c. 1905

-

Street scene in 1906

-

Snowy night in 1940

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 44.6 square miles (115.6 km2), of which 44.4 square miles (114.9 km2) is land and 0.27 square miles (0.7 km2), or 0.63%, is water.[14] The Ottauquechee River flows through the town.[15]

Woodstock is crossed by U.S. Route 4, Vermont Route 12 and Vermont Route 106. It is bordered the town of Pomfret to the north, Hartford to the northeast, Hartland to the east, Reading to the south, and Bridgewater to the west.

Woodstock is a three-hour drive from Boston and is 250 miles (400 km) away from New York City. It is easily accessible via car or plane to Rutland or Lebanon Airports. The closest regular public transportation hubs are in White River Junction (12 miles (19 km) east) and Rutland (48 miles (77 km) west).

Climate

This climatic region is typified by large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and cold (sometimes severely cold) winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Woodstock has a humid continental climate, abbreviated "Dfb" on climate maps.[16]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 1,605 | — | |

| 1800 | 2,132 | 32.8% | |

| 1810 | 2,672 | 25.3% | |

| 1820 | 2,610 | −2.3% | |

| 1830 | 3,044 | 16.6% | |

| 1840 | 3,315 | 8.9% | |

| 1850 | 3,041 | −8.3% | |

| 1860 | 3,062 | 0.7% | |

| 1870 | 2,910 | −5.0% | |

| 1880 | 2,815 | −3.3% | |

| 1890 | 2,545 | −9.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,557 | 0.5% | |

| 1910 | 2,545 | −0.5% | |

| 1920 | 2,370 | −6.9% | |

| 1930 | 2,469 | 4.2% | |

| 1940 | 2,512 | 1.7% | |

| 1950 | 2,613 | 4.0% | |

| 1960 | 2,786 | 6.6% | |

| 1970 | 2,608 | −6.4% | |

| 1980 | 3,214 | 23.2% | |

| 1990 | 3,212 | −0.1% | |

| 2000 | 3,232 | 0.6% | |

| 2010 | 3,048 | −5.7% | |

| 2014 (est.) | 2,996 | [17] | −1.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

As of the census[1] of 2010, there were 3,048 people, 1,388 households, and 877 families residing in the town. The population density was 72.6 people per square mile (28.0/km2). There were 1,775 housing units at an average density of 39.9 per square mile (15.4/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 98.08% White, 0.40% Black or African American, 0.22% Native American, 0.62% Asian, 0.25% from other races, and 0.43% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.80% of the population.

There were 1,388 households out of which 26.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.7% were couples living together and joined in either marriage or civil union, 8.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.8% were non-families. 29.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.24 and the average family size was 2.79.

In the town the population was spread out with 20.7% under the age of 18, 4.9% from 18 to 24, 23.9% from 25 to 44, 31.7% from 45 to 64, and 18.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45 years. For every 100 females there were 94.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.6 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $47,143, and the median income for a family was $57,330. Males had a median income of $33,229 versus $26,769 for females. The per capita income for the town was $28,326. About 4.3% of families and 6.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 8.3% of those under age 18 and 3.7% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

Annual cultural events

The annual Harvest Weekend at The Billings Farm and Museum is held in October and includes a husking bee, barn dance, and 19th century harvest activities.[19][20]

Tourism

The Billings Farm and Museum is a National Historic Landmark. The land and mansion were owned by Laurance Rockefeller and his wife Mary French Rockefeller. The farm and museum include an operating dairy farm and a restored 1890 farm house.[21][22]

Parks and recreation

The Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park is located in Woodstock, and is the only unit of the United States National Park System in Vermont (except for the Appalachian Trail). The park preserves the site where Frederick Billings established a managed forest and a progressive dairy farm.[21][23]

Education

Woodstock is served by Woodstock Elementary School and Woodstock Union High School & Middle School. The schools are part of the Windsor Central Supervisory Union.[24][25][26]

Notable people

- Fred C. Ainsworth, U.S. Army surgeon and Adjutant General[27]

- Ivan Albright, artist[28]

- Benjamin Allen, politician[29]

- Franklin S. Billings, 60th governor of Vermont[30]

- Franklin S. Billings, Jr., judge[31]

- Frederick H. Billings, lawyer, financier and railroad president[32]

- Keegan Bradley, PGA Tour golfer[33]

- Richard M. Brett, conservationist and author[34]

- Sylvester Churchill, journalist[35]

- Jacob Collamer, politician[36]

- Philip Cummings, lecturer on world affairs

- George Dewey, admiral[37]

- Maud Durbin, actress and wife of Otis Skinner[38]

- Harold "Duke" Eaton, Jr., Supreme Court Justice - State of Vermont

- Elon Farnsworth, attorney general of Michigan[39]

- Robert Hager, television journalist[40]

- Benjamin Tyler Henry, gunsmith and manufacturer[8]

- Rebecca Hammond Lard, poet from Indiana[41]

- Charles Marsh, US congressman[42]

- George Perkins Marsh, environmentalist[43]

- Joseph A. Mower, general[44]

- Hiram Powers, sculptor[45]

- Origen D. Richardson, politician[46]

- Laurance Rockefeller, financier and owner of the Woodstock Inn[21]

- Otis Skinner, actor[47][48]

- Benjamin Swan, longest serving Vermont State Treasurer[49]

- Andrew Tracy, US congressman[50]

- Gwen Verdon, dancer and actress[51]

- Peter T. Washburn, 31st Governor of Vermont[52]

- Hezekiah Williams, US congressman[53]

- Norman Williams, Vermont Auditor of Accounts and Secretary of State of Vermont[54]

- Daphne Zuniga, film and television actress[55]

In popular culture

- A Christmas commercial for Budweiser beer was shot mostly in the area of the village of South Woodstock. It features the Clydesdale horses pulling the brewer's dray.[citation needed]

- Several movies have been filmed in or around Woodstock, including Dr. Cook's Garden (1971),[56] Ghost Story (1981)[57] and Funny Farm (1988).[58]

Sites of interest

- Billings Farm & Museum

- Lincoln Covered Bridge, built in 1877

- Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park

- Middle Covered Bridge, built in 1969

- Taftsville Covered Bridge, built in 1836

- First Congregational Church of Woodstock, Vermont, the historic church of Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller

- Town Hall Theatre

- Woodstock Historical Society & Dana House Museum

-

Lincoln Covered Bridge

-

Taftsville Covered Bridge

See also

References

- ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ Title 24, Part I, Chapter 1, §15, Vermont Statutes. Accessed 2007-11-01.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Woodstock town, Windsor County, Vermont". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ Hayward's New England Gazetteer of 1839

- ^ a b A. J. Coolidge & J. B. Mansfield, A History and Description of New England; Boston, Massachusetts 1859

- ^ a b "Woodstock, Vermont". City-Data.com. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ Virtual Vermont -- Woodstock, Vermont

- ^ http://www.thevermontstandard.com/2010/08/wireless-woodstock-launched-by-governor/

- ^ a b Rybczynski, Witold. City Life: Urban Expectations in a New World New York: Scribner, 1995. pp.89-93. ISBN 0-684-81302-5.

- ^ http://www.planning.org/greatplaces/streets/2011/index.htm#VT

- ^ http://www.vermont.com/cities/woodstock/

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Woodstock town, Windsor County, Vermont". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ^ DeLorme (1996). Vermont Atlas & Gazetteer. Yarmouth, Maine: DeLorme. ISBN 0-89933-016-9

- ^ Climate Summary for Woodstock, Vermont

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ^ "Harvest Weekend at Billings Farm & Museum". Vermont Attractions Association. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ "Voted a Top 10 Fall Event for 2013! 29th Annual Harvest Weekend Featured at Billings Farm & Museum". Billings Farm & Museum. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Mary and Laurance Rockefellers' Billings Farm and the Farm & Museum". Vermont Standard. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ "Billings Farm and Museum". Billings Farm and Museum. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ "Marsh-Billings National Historical Park (VT)". James Hayes-Bohanan's Environmental Geography. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ "Woodstock Union High School & Middle School". Woodstock Union High School & Middle School. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ "Woodstock Elementary School". Woodstock Elementary School. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ "Woodstock Schools". GreatSchools, Inc. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ "Fred C. Ainsworth". Arlington National Cemetery. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Ivan Albright". 2014 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Benjamin Allen (1807-1873)". The Civil War and Northwest Wisconsin. Retrieved 2015-08-26.

- ^ "Franklin S. Billings". National Governors Association. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Franklin S. Billings". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Frederick H. Billings". 2014 Geni.com. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Keegan Bradley". 2014 ESPN Internet Ventures. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Richard M. Brett". 2013 The New York Times Company. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Sylvester Churchill". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "Jacob Collamer". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ Karr, Paul. Frommer's Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. John Wiley & Sons, Jun 17, 2010. p. 126.

- ^ Maud Durbin at Find A Grave

- ^ "Elon Farnsworth". 2013 Michigan Supreme Court Historical Society. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ "Robert Hager". 2014 NBCNews.com. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ "Rebecca Hammond Lard". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ "Charles Marsh". 2010 by the Litchfield Historical Society. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ "George Perkins Marsh". 2014 The Vermont Standard. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ "Joseph A. Mower". Encyclopedia of the American Civil War. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ "Hiram Powers". 2000–2014 The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ Morton, Julius Sterling and Watkins, Albert (1911). Illustrated History of Nebraska: A History of Nebraska from the Earliest Explorations of the Trans-Mississippi Region, with Steel Engravings, Photogravures, Copper Plates, Maps and Tables, Volume 1. Western Pub. and Engraving Company. p. 205.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Otis Skinner at Find A Grave

- ^ New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division, First Department (1937). New York Supreme Court Cases Heard on Appeal. Case Press, Inc. p. 145.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Henry Swan Dana, History of Woodstock, Vermont, 1889, pages 485-486

- ^ "Andrew Tracy". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ "Gwen Verdon". 2014 Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ "Peter T. Washburn". National Governors Association. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ "Hezekiah Williams". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ Dana, Henry Swan (1889). History of Woodstock, Vermont. Houghton, Mifflin and Company. pp. 475–476.

- ^ "Daphne Zuniga". TV.com. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0065657/

- ^ http://blog.timesunion.com/localarts/is-salt-the-best-movie-made-in-the-capital-region/6207/

- ^ http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0095188/

External links

- Town of Woodstock official website

- Norman Williams Public Library

- Woodstock Area Chamber of Commerce

- The Vermont Standard, local newspaper

- ePodunk