Youngblood (comics)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2014) |

| Youngblood | |

|---|---|

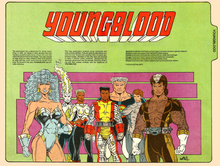

Cover to Youngblood #1 (April 1992) by Rob Liefeld | |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | Various |

| First appearance | Megaton Explosion #1 (June 1987) |

| Created by | Rob Liefeld |

| In-story information | |

| Base(s) | Pentagon |

| Member(s) | Badrock Doc Rocket Sentinel Shaft Suprema Vogue Former members Big Brother Brahma Chapel Combat Diehard Cougar Task Dutch Johnny Panic Knightsabre Masada Photon Psi-Fire Riptide Troll Twilight Scion |

Youngblood is a superhero team that starred in their self-titled comic book, created by writer/artist Rob Liefeld.[1][2][3] The team made its debut as a backup feature in the 1987 one-shot Megaton Explosion #1 before later appearing in 1992 in its own ongoing series as the flagship publication for Image Comics. Youngblood was originally published by Image Comics, and later by Awesome Entertainment. Upon Rob Liefeld's return to Image Comics, it was revived in 2008 and again in 2012.

Youngblood was a high-profile superteam sanctioned and overseen by the United States government. Youngblood's members include Shaft, a former FBI agent who uses a high-tech bow and arrow; Badrock, a teenager transformed into a living block of stone;[4] Vogue, a Russian fashion model with purple-and-chalk-white skin; and Chapel, a government assassin.

Publication history

Origins of the series

Youngblood was inspired by creator Rob Liefeld's idea that if superheroes existed in real life, they would be treated as celebrities, much the same way as movie stars and athletes. The series, therefore, depicts the superhero members of Youngblood not only as they participate in adventures fighting crime and evil, but navigating the world of celebrity endorsement deals, TV show appearances, agents, managers and the perceived pressures of celebrity life.[5]

From 1985 to 1987, Liefeld did pinups for Megaton Comics, including one of the character Ultragirl that would see print in Megaton Comics Explosion #1 (June 1987), a "who's who"-type reference book featuring individual entries of characters in the style of an encyclopedia or handbook. Carlson gave Liefeld an opportunity for his own creation, Youngblood to see print in this form. The two-page entry featuring the team (consisting at that point of Sentinel, Sonic, Brahma, Riptide, Cougar, Psi-Fire and Photon) was the team's first appearance in print.[6][7][8][9][10]

Two months later the team appeared in an advertisement in Megaton #8 (August 1987)[8][11] indicating that it would next appear in Megaton Special # 1, by Liefeld and writer Hank Kanalz, with a cover by artist Jerry Ordway. However, Megaton Comics went out of business before that comic was printed.[8][12]

Liefeld has explained that the version of Youngblood that eventually saw print in Youngblood #1 was based partially on his 1991 plan for a new Teen Titans series for DC Comics, to be co-written with Marv Wolfman. According to Liefeld, he and managing editor Dick Giordano failed to reach an agreement on the project, and Liefeld merged his Teen Titans ideas with his previous, creator-owned Youngblood property. According to Liefeld, "Shaft was intended to be Speedy. Vogue was a new Harlequin design, Combat was a Kh'undian warrior circa the Legion of Super-Heroes, ditto for Photon and Die Hard was a S.T.A.R. Labs android. I forgot who Chapel was supposed to be, but I'm sure it would have rocked". Given the failed deal with DC, and Liefeld's increasingly strained relationship with Marvel Comics over his X-Force royalties, he joined other Marvel artists to form Image Comics, in order to publish Youngblood in their own series.[13] Youngblood #1 would be an anthology consisting of two separate stories published in flip book format (meaning that reading the second story required the reader to turn the book upside down and begin reading with the back cover. Not to be confused with animation flip books.)[3]

A sneak preview of the series appeared in The Malibu Sun #1 (February 1992), published by Image through Malibu Comics, which provided administrative, production, distribution, and marketing support for Image's early publications.[14][15] On March 13, two separate 5½" x 8½″ black-and-white ashcan editions of Youngblood began to surface, each featuring one of two separate stories from Youngblood #1. Edition "A" featured the 13-page lead story, while Edition "B" featured other side of the flip book, along with four extra pages of art that would not be included in Youngblood #1. According to Image Comics spokesperson John Beck, the print run on edition "A" was 1,000 copies, and edition "B" was limited to 500 copies.[8]

Youngblood #1 (April 1992) was the first Image Comics publication.[16] At the time of its release, it was the highest selling independent comic book published, despite receiving poor reviews from critics.[17] for the unclear storytelling effected by both Liefeld's art, and the book's flip format, which some readers found confusing; poor anatomy; incorrect perspective; non-existent backgrounds; poor dialogue and the late shipping of the book, a problem that continued with subsequent issues. In an interview in Hero Illustrated #4 (October 1993), Liefeld conceded disappointment with the first four issues of Youngblood, calling the first issue a "disaster". He explained that production problems, as well as sub-par scripting by his friend and collaborator Hank Kanalz, whose employment Liefeld later terminated, resulted in work that was lower in quality than that which Liefeld produced when Fabian Nicieza scripted his plots on X-Force, and that reprints of those four issues would be re-scripted. Writer and columnist Peter David pointed to Liefeld's scapegoating of Kanalz as an example of Liefeld's failure to take responsibility for his project, and evidence that genuine collaboration with good writers like Louise Simonson and Fabian Nicieza, which some of the Image founders did not appreciate, had previously reflected better on Liefeld's art.[3][18][19] Throughout its run at Image, Youngblood, as well as other books published by Liefeld's Extreme Studios, were attacked by critics for late issues and inconsistent quality.[20]

In 1993, Liefeld solicited writer Kurt Busiek for Youngblood stories. Busiek wrote detailed plots for three issues and ideas for a fourth, under the proposed title: Youngblood: Year One. This was never produced, but the plot lines were revived amid controversy years later.[citation needed]

In the mid-1990s, Liefeld had a falling out with his Image partners, forcing him to leave the company and take Youngblood with him.[21][22]

Alan Moore

In 1997, Liefeld hired Alan Moore to relaunch and revamp Youngblood. Moore's run on the title began with a miniseries entitled Judgment Day which revolved around the mysterious murder of Youngblood member Riptide, the subsequent "super-trial" of teammate Knightsabre and the all-powerful Book of All Stories which dictates the order of the universe.[23]

Moore created a new, teenage Youngblood group that was financed independently by millionaire Waxey Doyle, formerly the WWII superhero Waxman. The team was led by Shaft and was augmented by new members Big Brother, Doc Rocket, Twilight, Suprema and Johnny Panic. Moore said he wanted Youngblood to be a "less sprawling, more dynamic team" and that: "if you have more characters than [six], the action gets cluttered and it becomes increasingly difficult to establish each character as a real and solid person in their own right".[24] All of the new team members, and most of the villains featured in this series including Jack-A-Dandy, were Moore's creations.[24]

However, despite Moore's plans for at least twelve issues of his new Youngblood, only three issues were ever printed, and the third issue was published in another book called Awesome Adventures. The team also appeared in a short story in the Awesome Christmas Special where Shaft's journal provides the narration as the new team comes together.[citation needed]

Moore's rough outline for the series was published in Alan Moore's Awesome Handbook and included a budding relationship between Big Brother and Suprema, a giant planet-devouring entity called "The Goat", Shaft's fruitless crush on Twilight, and the revelation that Johnny Panic was the biological son of Supreme villain Darius Dax. In the Handbook, Moore also reveals that he intentionally chose the team members for their connections to various points, and significant characters, in the Awesome Universe's superhero history (ex. Supreme), noting this as the case in the 1980s launch of The New Teen Titans.[citation needed]

Youngblood: Genesis

In 2000, Liefeld began soliciting orders for Youngblood: Genesis, using Kurt Busiek's unused Year One plots. Busiek asked that he only be credited with providing the plots for this new series. He was listed as plotter on the comic book itself when it came out years later, but when Liefeld advertised the comic through Diamond Previews "as written by Kurt Busiek", Busiek accused him of not honoring their agreement, and eventually asked that his fans not buy the series.[25]

Youngblood: Genesis officially ended after two issues, as the third and fourth issues would have used Image Comics characters for which Liefeld did not have the appropriate permissions. According to Liefeld: "I have the original issues #3 and #4 that Kurt wrote, [but] they can't be produced as is simply from the standpoint that they heavily feature prominent supporting cast members from Spawn and Wildcats, as well as Lynch from Gen¹³ and Team 7".[26]

2004–present

A number of projects were announced in 2003 including reprinting older material[27] and providing the art for two Youngblood series.[28] The two new comic books involved Mark Millar writing new issues of Youngblood: Bloodsport[29] and Youngblood: Genesis written by Brandon Thomas.[30] However, only one issue of the Youngblood: Bloodsport was published but in June 2008 Liefeld announced that issue #2 would appear in September.[31]

In 2004, Robert Kirkman began writing a new series, Youngblood: Imperial, with artist Marat Mychaels[26] but left after one issue due to his busy schedule. Fabian Nicieza was slated to take over,[32] but so far issues #2–3 have yet to appear.

In 2005, Liefeld announced that Joe Casey would be re-assembling and re-scripting the original Youngblood miniseries into a more coherent and sophisticated story, to be titled Maximum Youngblood. On July 12, 2007, it was announced [33] that Liefeld would return to Image Comics to publish a collected "definitive version" of Maximum Youngblood with a new ending written by Joe Casey, illustrated by Liefeld himself.[34] This was followed in January 2008 by a new ongoing series (Youngblood Volume 4) written by Casey and illustrated by Derec Donovan, with covers by Liefeld. Liefeld was slated to begin writing and art duties on Youngblood beginning in May 2009.[35][36] No new issues have come out since then, with Youngblood Volume 4 ending with only nine issues.

In late 2011 it was announced that screenwriter John McLaughlin would write a revival of Youngblood with artist Jon Malin and series creator Rob Liefeld for May 2012 release, starting with Youngblood #71, as the series reverts to its original legacy numbering.[37] The series ran for 8 issues, concluding with #78 in July 2013.

For the 25th anniversary of both Youngblood and Image Comics, Liefeld announced that a new ongoing series (Youngblood Volume 5) written by Chad Bowers with art by Jim Towe would be launched in May 2017.[38]

Reaction and impact

As Youngblood #1 is the comic book that introduced Image Comics, it is ranked #19 on Comic Book Resources's 2008 chronological list of the 20 Most Significant Comics. According to CBR's Steven Grant, this status is derived not so much from the comic's content, but for triggering both the 1990s speculator boom and bust, and the trend towards the creation of superhero universes among various publishers. The series, and the formation of Image itself, is credited with discouraging publishers' emphasis on their creative talent in their marketing decisions.[39]

Collected editions

A number of the comic books have been collected into trade paperbacks:

- Youngblood TPB (collects Youngblood Volume 1, #1–4; 96 pages; 1993 Previews Exclusive Edition)

- Youngblood: Baptism of Fire TPB (collects Youngblood Volume 1, #6–8 and 10, Team Youngblood #9–11, and the Troll story from Image Comics Zero; Image Comics; 1996)

- Youngblood, Volume 1 (collects Youngblood Volume 1, #0–10; remastered as Maximum Edition, 168 pages, Image Comics, hardcover, December 2008, ISBN 1-58240-858-0)

- Youngblood, Volume 1: Focus Tested (collects Youngblood Volume 4, #1–4; includes introduction by Robert Kirkman, plus interviews with Joe Casey and Rob Liefeld; 104 pages, Image Comics, September 2008, ISBN 1-58240-945-5)

- Youngblood, Volume 2: Voted Off the Island (collects Youngblood Volume 4, #5–9; 128 pages, Image Comics, November 2008, ISBN 1-60706-003-5)

In other media

A half-hour Youngblood animated series was planned for the 1995–96 season on Fox as part of an hour block with a proposed Cyberforce series.[20] The series was being developed by Roustabout Productions, a newly formed animation company. According to Nick Dubois, creative director and co-founder of Roustabout, the series would take a lighthearted approach with tongue-in-cheek humor.[40] A clip was created but the series was never produced. The clip aired in commercials for Youngblood action figures.

In February 2009, Collider reported that Reliance Entertainment acquired the feature film rights to the comic book, reportedly for a mid-six figures, with Brett Ratner attached to direct.[41]

References

- ^ "New Blood: Joe Casey talks 'Youngblood' – Comic Book Resources". CBR.com. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Rob Liefeld Talks 'Youngblood: Bloodsport'". CBR.com. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Ginocchio, Mark (July 3, 2013). "Gimmick or Good? – Youngblood #1". CBR.com.

- ^ Upon Youngblood's debut, the character's name was originally "Bedrock". Liefeld would later change the character's name to "Badrock" to avoid confusion and legal threats from Hanna-Barbera, who owned the copyright to The Flintstones, which is set in the fictional town of Bedrock.[citation needed]

- ^ Helvie, Forrest (January 9, 2013). "Sharpening The Image: Rob Liefeld's Youngblood, the Man and the Comic that Started It All: Part Four: Final Thoughts". Sequart Organization.

- ^ Carlson, Gary (September 4, 2013). "Youngblood & Rob Liefeld". Big Bang Comics.

- ^ "Megaton Explosion". Megaton. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Offenberger, Rik (May 29, 1992). "'Youngblood' ashcans have been printed". First Comics News.

- ^ Katz, Jay (June 9, 2015). "Creator Spotlight – Rob Liefeld". InvestComics LLC. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ "CGC 9.4 SS Megaton Explosion 1'st App Youngblood by Deadpool Creator Rob Liefeld". WorthPoint. February 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ "Megaton #8". Grand Comics Database. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ "Megaton #8". Megaton. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ Cronin, Brian (June 9, 2005). "Comic Book Urban Legends Revealed #2!". CBR.com.

- ^ "Bye Bye Marvel: Here Comes Image: Portacio, Claremont, Liefeld, Jim Lee Join McFarlane's New Imprint at Malibu". The Comics Journal #148 (February 1992). Fantagraphics Books. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Platinum Studios: Awesome Comics Archived February 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Accessed February 3, 2008

- ^ Reed, Patrick, A. (February 1, 2016). "On This Day In 1992: The Start Of The Image Comics Revolution". Comics Alliance.

- ^ "Youngblood" Archived 2017-04-01 at the Wayback Machine. Comic Book Roundup. Retrieved May 1, 2017.

- ^ Hollan, Michael (January 7, 2017). "Rob Liefeld’s Most Controversial Comics Titles". CBR.com.

- ^ David, Peter. "Giving Credit Where Credit is Due, Part 1". peterdavid.net. August 20, 2010. Reprinted from Comics Buyer's Guide #1033 (September 3, 1993)

- ^ a b Thomas, Michael (July 30, 2001). "To the Extreme: A conversation with Rob Liefeld". CBR.com.

- ^ Dean, Michael. (July 2000). "The Image Story: Part Three: What Went Wrong". The Comics Journal. pp. 7 - 11.

- ^ "Chapter Three: Image Litigation, Cont.". The Comics Journal #192 (December 1996), pp. 17-19.

- ^ Callahan, Tim. "The Great Alan Moore Reread: Judgment Day". Tor. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- ^ a b McLauchlin, Jim (August 1997). "'Y2' Relaunches Youngblood". Wizard. No. 72. p. 25.

- ^ "Savant Magazine's analysis of the Busiek/Liefeld controversy". Archived from the original on 2001-02-15.

- ^ a b "Kirkman & Liefeld on the Return of Youngblood". Newsarama. June 29, 2004. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Maximum Rob – Liefeld Talks 'Old' & New Projects". Newsarama. July 11, 2005. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ong Pang Kean, Benjamin (July 2, 2003). "Youngblood-A-Trois I: Rob Liefeld". Newsarama. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ong Pang Kean, Benjamin (July 3, 2003). "Youngblood-A-Trois II: Mark Millar". Newsarama. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ong Pang Kean, Benjamin (July 4, 2003). "Youngblood-A-Trois III: Brandon Thomas". Newsarama. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Manning, Shaun (June 19, 2008). "Rob Liefeld Talks 'Youngblood: Bloodsport'". CBR.com.

- ^ Brady, Matt (October 1, 2004). "Liefeld: Kirkman off of Youngblood Imperial, Nicieza on". Newsarama. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brady, Matt (July 7, 2007). "Liefeld/Image Reunite for Youngblood HC/New Series". Newsarama. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Rob Liefeld Talks Youngblood's Return to Image". Newsarama. August 1, 2007. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Brady, Matt (August 2, 2007). "Joe Casey: Youngblood's New Blood". Newsarama. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "New Blood: Joe Casey talks Youngblood". CBR.com. December 6, 2007.

- ^ Wigler, Josh (July 1, 2009). "Rob Liefeld Talks Youngblood". CBR.com.

- ^ Polanco, Tony (February 23, 2017). "Image Comics' Youngblood Returns This May". Geek.com.

- ^ Grant, Steven (October 22, 2008). "Permanent Damage – The 20 Most Significant Comics". CBR.com.

- ^ "Youngblood Animated Series in the Works for Late '94". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 54. EGM Media, LLC. January 1994. p. 292.

- ^ Weintraub, Steve (February 9, 2009). "Brett Ratner to Direct Rob Liefeld's YOUNGBLOOD". Collider.

External links

- Youngblood at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)