Zone rouge

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (March 2016) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (June 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

50°22′N 2°48′E / 50.36°N 2.80°E

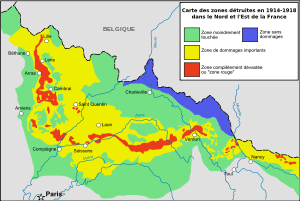

The zone rouge (English: red zone) is a chain of non-contiguous areas throughout northeastern France that the French government isolated after the First World War. The land, which originally covered more than 1,200 square kilometres (460 sq mi), was deemed to be physically and environmentally too damaged by the conflict for human habitation. Rather than attempt to immediately clean up the former battlefields, the land was allowed to return to nature. Restrictions within the zone rouge still exist today although the control areas have been greatly reduced.

The "zone rouge" was defined just after the war as "Completely devastated. Damage to properties: 100%. Damage to Agriculture: 100%. Impossible to clean. Human life impossible".[1]

Under French law, activities such as housing, farming or forestry, were temporarily or permanently forbidden in the zone rouge. This was because of the vast amounts of human and animal remains and millions of items of unexploded ordnance contaminating the land. Some towns and villages were never permitted to be rebuilt after the war.

Main dangers

The area is saturated with unexploded shells (including many gas shells), grenades, and rusty ammunition. Soils were heavily polluted by lead, mercury, chlorine, arsenic, various dangerous gases, acids, and human and animal remains.[1] The area was also littered with ammunition depots and chemical plants.

Each year dozens of tons of unexploded shells are recovered. According to the Sécurité Civile agency in charge, at the current rate no fewer than 700 more years will be needed to completely clean the area. Some experiments conducted in 2005–06 discovered up to 300 shells/10,000 m2 in the top 15 cm of soil in the worst areas.[1][failed verification]

Some areas remain off limits (for example two small pieces of land close to Ypres and Woëvre) where 99% of all plants still die as arsenic can constitute up to 17% of some soil samples (Bausinger, Bonnaire, and Preuß, 2007).

See also

References

Further reading

- Smith, Corinna Haven & Hill, Caroline R. Rising Above the Ruins in France: An Account of the Progress Made Since the Armistice in the Devastated Regions in Re-establishing Industrial Activities and the Normal Life of the People. New York: GP Putnam's Sons, 1920: 6.

- De Sousa David, La Reconstruction et sa Mémoire dans les villages de la Somme 1918–1932, Editions La vague verte, 2002, 212 pages

- Bonnard Jean-Yves, La reconstitution des terres de l'Oise après la Grande Guerre: les bases d'une nouvelle géographie du foncier, in Annales Historiques Compiégnoises 113–114, p.25-36, 2009.

- Parent G.-H., 2004. Trois études sur la Zone Rouge de Verdun, une zone totalement sinistrée I.L’herpétofaune – II.La diversité floristique – III.Les sites d‘intérêt botanique et zoologique à protéger prioritairement. Ferrantia, 288 pages

- Bausinger, Tobias; Bonnaire, Eric; & Preuß, Johannes,. Exposure assessment of a burning ground for chemical ammunition on the Great War battlefields of Verdun, Science of the Total Environment 382:2-3, pp. 259–271, 2007.

External links

- Map of the Western Front in 1918 Template:En icon

- Déminage à Douaumont Template:Fr icon Template:En icon

- National Geographic: France’s Zone Rouge is a Lingering Reminder of World War I Template:En icon