Corannulene

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Dibenzo[ghi,mno]fluoranthene[1]

| |

| Other names

[5]circulene; Buckybowl

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C20H10 | |

| Molar mass | 250.29 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

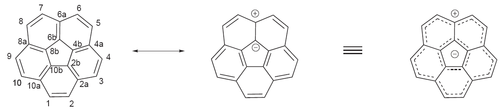

Corannulene is a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon with chemical formula C20H10.[2] The molecule consists of a cyclopentane ring fused with 5 benzene rings, so another name for it is [5]circulene. It is of scientific interest because it is a geodesic polyarene and can be considered a fragment of buckminsterfullerene. Due to this connection and also its bowl shape, corannulene is also known as a buckybowl. Buckybowls are fragments of buckyballs. Corannulene exhibits a bowl-to-bowl inversion with an inversion barrier of 10.2 kcal/mol (42.7 kJ/mol) at −64 °C.[3]

Synthesis

[edit]Several synthetic routes exist to corannulene. Flash vacuum pyrolysis techniques generally have lower chemical yields than solution-chemistry syntheses, but offer routes to more derivatives. Corannulene was first isolated in 1966 by multistep organic synthesis.[4] In 1971, the synthesis and properties of corannulane were reported.[5] A flash vacuum pyrolysis method followed in 1991.[6] One synthesis based on solution chemistry[7] consists of a nucleophilic displacement–elimination reaction of an octabromide with sodium hydroxide:

The bromine substituents are removed with an excess of n-butyllithium.

A kilogram scale synthesis of corannulene has been achieved.[8]

Much effort is directed at functionalization of the corannulene ring with novel functional groups such as ethynyl groups,[3][9][10] ether groups,[11] thioether groups,[12] platinum functional groups,[13] aryl groups,[14] phenalenyl fused [15] and indeno extensions.[16] and ferrocene groups.[17]

Aromaticity

[edit]The observed aromaticity for this compound is explained with a so-called annulene-within-an-annulene model. According to this model corannulene is made up of an aromatic 6 electron cyclopentadienyl anion surrounded by an aromatic 14 electron annulenyl cation. This model was suggested by Barth and Lawton in the first synthesis of corannulene in 1966.[4] They also suggested the trivial name 'corannulene', which is derived from the annulene-within-an-annulene model: core + annulene.

However, later theoretical calculations have disputed the validity of this approximation.[18][19]

Reactions

[edit]Reduction

[edit]Corannulene can be reduced up to a tetraanion in a series of one-electron reductions. This has been performed with alkali metals, electrochemically and with bases. The corannulene dianion is antiaromatic and tetraanion is again aromatic. With lithium as reducing agent two tetraanions form a supramolecular dimer with two bowls stacked into each other with 4 lithium ions in between and 2 pairs above and below the stack.[20] This self-assembly motif was applied in the organization of fullerenes. Penta-substituted fullerenes (with methyl or phenyl groups) charged with five electrons form supramolecular dimers with a complementary corannulene tetraanion bowl, 'stitched' by interstitial lithium cations.[21] In a related system 5 lithium ions are sandwiched between two corannulene bowls [22]

In one cyclopenta[bc]corannulene a concave - concave aggregate is observed by NMR spectroscopy with 2 C–Li–C bonds connecting the tetraanions.[23]

Metals tend to bind to the convex face of the annulene. Concave binding has been reported for a cesium / crown ether system [24]

Oxidation

[edit]UV 193-nm photoionization effectively removes a π-electron from the twofold degenerate E1-HOMO located in the aromatic network of electrons yielding a corannulene radical cation.[25] Owing to the degeneracy in the HOMO orbital, the corannulene radical cation is unstable in its original C5v molecular arrangement, and therefore, subject to Jahn-Teller (JT) vibronic distortion.

Using electrospray ionization, a protonated corannulene cation has been produced in which the protonation site was observed to be on a peripheral sp2-carbon atom.[25]

Reaction with electrophiles

[edit]Corannulene can react with electrophiles to form a corannulene carbocation. Reaction with chloromethane and aluminium chloride results in the formation of an AlCl4− salt with a methyl group situated at the center with the cationic center at the rim. X-ray diffraction analysis shows that the new carbon-carbon bond is elongated (157 pm) [26]

Bicorannulenyl

[edit]Bicorannulenyl is the product of dehydrogenative coupling of corannulene. With the formula C20H9-C20H9, it consists of two corannulene units connected through a single C-C bond. The molecule's stereochemistry consists of two chiral elements: the asymmetry of a singly substituted corannulenyl, and the helical twist about the central bond. In the neutral state, bicorannulenyl exists as 12 conformers, which interconvert through multiple bowl-inversions and bond-rotations.[27] When bicorannulenyl is reduced to a dianion with potassium metal, the central bond assumes significant double-bond character. This change is attributed to the orbital structure, which has a LUMO orbital localized on the central bond.[28] When bicorannulenyl is reduced to an octaanion with lithium metal, it self-assembles into supramolecular oligomers.[29] This motif illustrates "charged polyarene stacking".

Research

[edit]

The corannulene group is used in host–guest chemistry with interactions based on pi stacking, notably with fullerenes (the buckycatcher) [30][31] but also with nitrobenzene[32]

Alkyl-substituted corannulenes form a thermotropic hexagonal columnar liquid crystalline mesophase.[33] Corannulene has also been used as the core group in a dendrimer.[14] Like other PAHs, corannulene ligates metals.[34][35][36][37][38][39][40] Corannulenes with ethynyl groups are investigated for their potential use as blue emitters.[10] The structure was analyzed by infrared spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy.[41]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Fluoranthene is so named for its fluorescent property. It is not a fluorine compound.

- ^ Scott, L. T.; Bronstein, H. E.; Preda, D. V.; Ansems, R. B. M.; Bratcher, M. S.; Hagen, S. (1999). "Geodesic polyarenes with exposed concave surfaces". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 71 (2): 209. doi:10.1351/pac199971020209. S2CID 37901191.

- ^ a b Scott, L. T.; Hashemi, M. M.; Bratcher, M. S. (1992). "Corannulene bowl-to-bowl inversion is rapid at room temperature". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 114 (5): 1920–1921. doi:10.1021/ja00031a079.

- ^ a b Barth, W. E.; Lawton, R. G. (1966). "Dibenzo[ghi,mno]fluoranthene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 88 (2): 380–381. doi:10.1021/ja00954a049.

- ^ Lawton, Richard G.; Barth, Wayne E. (April 1971). "Synthesis of corannulene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 93 (7): 1730–1745. doi:10.1021/ja00736a028. S2CID 94872875.

- ^ Scott, L. T.; Hashemi, M. M.; Meyer, D. T.; Warren, H. B. (1991). "Corannulene. A convenient new synthesis". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 113 (18): 7082–7084. doi:10.1021/ja00018a082.

- ^ Sygula, A.; Rabideau, P. W. (2000). "A Practical, Large Scale Synthesis of the Corannulene System". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 122 (26): 6323–6324. doi:10.1021/ja0011461.

- ^ Butterfield, A.; Gilomen, B.; Siegel, J. (2012). "Kilogram-Scale Production of Corannulene". Organic Process Research & Development. 16 (4): 664–676. doi:10.1021/op200387s.

- ^ Wu, Y.; Bandera, D.; Maag, R.; Linden, A.; Baldridge, K.; Siegel, J. (2008). "Multiethynyl corannulenes: synthesis, structure, and properties". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (32): 10729–10739. doi:10.1021/ja802334n. PMID 18642812.

- ^ a b Mack, J.; Vogel, P.; Jones, D.; Kaval, N.; Sutton, A. (2007). "The development of corannulene-based blue emitters". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 5 (15): 2448–2452. doi:10.1039/b705621d. PMID 17637965.

- ^ Gershoni-Poranne, R.; Pappo, D.; Solel, E.; Keinan, E. (2009). "Corannulene ethers via Ullmann condensation". Organic Letters. 11 (22): 5146–5149. doi:10.1021/ol902352k. PMID 19905024.

- ^ Baldridge, K.; Hardcastle, K.; Seiders, T.; Siegel, J. (2010). "Synthesis, structure and properties of decakis(phenylthio)corannulene". Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 8 (1): 53–55. doi:10.1039/b919616a. PMID 20024131.

- ^ Choi, H.; Kim, C.; Park, K. M.; Kim, J.; Kang, Y.; Ko, J. (2009). "Synthesis and structure of penta-platinum σ-bonded derivatives of corannulene". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 694 (22): 3529–3532. doi:10.1016/j.jorganchem.2009.07.015.

- ^ a b Pappo, D.; Mejuch, T.; Reany, O.; Solel, E.; Gurram, M.; Keinan, E. (2009). "Diverse Functionalization of Corannulene: Easy Access to Pentagonal Superstructure". Organic Letters. 11 (5): 1063–1066. doi:10.1021/ol8028127. PMID 19193048.

- ^ Nishida, S.; Morita, Y.; Ueda, A.; Kobayashi, T.; Fukui, K.; Ogasawara, K.; Sato, K.; Takui, T.; Nakasuji, K. (2008). "Curve-structured phenalenyl chemistry: synthesis, electronic structure, and bowl-inversion barrier of a phenalenyl-fused corannulene anion". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (45): 14954–14955. doi:10.1021/ja806708j. PMID 18937470.

- ^ Steinberg, B.; Jackson, E.; Filatov, A.; Wakamiya, A.; Petrukhina, M.; Scott, L. (2009). "Aromatic pi-systems more curved than C(60). The complete family of all indenocorannulenes synthesized by iterative microwave-assisted intramolecular arylations". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 131 (30): 10537–10545. doi:10.1021/ja9031852. PMID 19722628.

- ^ Topolinski, Berit; Schmidt, Bernd M.; Kathan, Michael; Troyanov, Sergej I.; Lentz, Dieter (2012). "Corannulenylferrocenes: towards a 1D, non-covalent metal–organic nanowire". Chem. Commun. 48 (50): 6298–6300. doi:10.1039/C2CC32275G. PMID 22595996.

- ^ Sygula, A.; Rabideau, P. W. (1995). "Structure and inversion barriers of corannulene, its dianion and tetraanion. An ab initio study". Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM. 333 (3): 215–226. doi:10.1016/0166-1280(94)03961-J.

- ^ Monaco, G.; Scott, L.; Zanasi, R. (2008). "Magnetic euripi in corannulene". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 112 (35): 8136–8147. Bibcode:2008JPCA..112.8136M. doi:10.1021/jp8038779. PMID 18693706.

- ^ Ayalon, A.; Sygula, A.; Cheng, P.; Rabinovitz, M.; Rabideau, P.; Scott, L. (1994). "Stable High-Order Molecular Sandwiches: Hydrocarbon Polyanion Pairs with Multiple Lithium Ions Inside and out". Science. 265 (5175): 1065–1067. Bibcode:1994Sci...265.1065A. doi:10.1126/science.265.5175.1065. PMID 17832895. S2CID 4979579.

- ^ Aprahamian, I.; Eisenberg, D.; Hoffman, R.; Sternfeld, T.; Matsuo, Y.; Jackson, E.; Nakamura, E.; Scott, L.; Sheradsky, T.; Rabinovitz, M. (2005). "Ball-and-socket stacking of supercharged geodesic polyarenes: bonding by interstitial lithium ions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (26): 9581–9587. doi:10.1021/ja0515102. PMID 15984885.

- ^ Zabula, A. V. (2011). "A Main Group Metal Sandwich: Five Lithium Cations Jammed Between Two Corannulene Tetraanion Decks". Science. 333 (6045): 1008–1011. Bibcode:2011Sci...333.1008Z. doi:10.1126/science.1208686. PMID 21852497. S2CID 1125747.

- ^ Aprahamian, I.; Preda, D.; Bancu, M.; Belanger, A.; Sheradsky, T.; Scott, L.; Rabinovitz, M. (2006). "Reduction of bowl-shaped hydrocarbons: dianions and tetraanions of annelated corannulenes". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 71 (1): 290–298. doi:10.1021/jo051949c. PMID 16388648.

- ^ Spisak, S. N.; Zabula, A. V.; Filatov, A. S.; Rogachev, A. Y.; Petrukhina, M. A. (2011). "Selective Endo and Exo Binding of Alkali Metals to Corannulene". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 50 (35): 8090–8094. doi:10.1002/anie.201103028. PMID 21748832.

- ^ a b Galué, Héctor Alvaro; Rice, Corey A.; Steill, Jeffrey D.; Oomens, Jos (1 January 2011). "Infrared spectroscopy of ionized corannulene in the gas phase" (PDF). The Journal of Chemical Physics. 134 (5): 054310. Bibcode:2011JChPh.134e4310G. doi:10.1063/1.3540661. PMID 21303123.

- ^ Zabula, A. V.; Spisak, S. N.; Filatov, A. S.; Rogachev, A. Y.; Petrukhina, M. A. (2011). "A Strain-Releasing Trap for Highly Reactive Electrophiles: Structural Characterization of Bowl-Shaped Arenium Carbocations". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 50 (13): 2971–2974. doi:10.1002/anie.201007762. PMID 21404379.

- ^ Eisenberg, D.; Filatov, A.; Jackson, E.; Rabinovitz, M.; Petrukhina, M.; Scott, L.; Shenhar, R. (2008). "Bicorannulenyl: stereochemistry of a C40H18 biaryl composed of two chiral bowls". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 73 (16): 6073–6078. doi:10.1021/jo800359z. PMID 18505292.

- ^ Eisenberg, D.; Quimby, J. M.; Jackson, E. A.; Scott, L. T.; Shenhar, R. (2010). "The Bicorannulenyl Dianion: A Charged Overcrowded Ethylene". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 49 (41): 7538–7542. doi:10.1002/anie.201002515. PMID 20814993.

- ^ Eisenberg, D.; Quimby, J. M.; Jackson, E. A.; Scott, L. T.; Shenhar, R. (2010). "Highly Charged Supramolecular Oligomers Based on the Dimerization of Corannulene Tetraanion". Chemical Communications. 46 (47): 9010–9012. doi:10.1039/c0cc03965a. PMID 21057679.

- ^ Sygula, A.; Fronczek, F.; Sygula, R.; Rabideau, P.; Olmstead, M. (2007). "A double concave hydrocarbon buckycatcher". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 129 (13): 3842–3843. doi:10.1021/ja070616p. PMID 17348661. S2CID 25154754.

- ^ Wong, B. M. (2009). "Noncovalent interactions in supramolecular complexes: a study on corannulene and the double concave buckycatcher". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 30 (1): 51–56. arXiv:1004.4243. doi:10.1002/jcc.21022. PMID 18504779. S2CID 18247078.

- ^ Kobryn, L.; Henry, W. P.; Fronczek, F. R.; Sygula, R.; Sygula, A. (2009). "Molecular clips and tweezers with corannulene pincers". Tetrahedron Letters. 50 (51): 7124–7127. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.09.177.

- ^ Miyajima, D.; Tashiro, K.; Araoka, F.; Takezoe, H.; Kim, J.; Kato, K.; Takata, M.; Aida, T. (2009). "Liquid crystalline corannulene responsive to electric field". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 131 (1): 44–45. doi:10.1021/ja808396b. PMID 19128171.

- ^ Seiders, T. Jon; Baldridge, Kim K.; O'Connor, Joseph M.; Siegel, Jay S. (1997). "Hexahapto Metal Coordination to Curved Polyaromatic Hydrocarbon Surfaces: The First Transition Metal Corannulene Complex". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 (20): 4781–4782. doi:10.1021/ja964380t.

- ^ Siegel, Jay S.; Baldridge, Kim K.; Linden, Anthony; Dorta, Reto (2006). "d8 Rhodium and Iridium Complexes of Corannulene". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (33): 10644–10645. doi:10.1021/ja062110x. PMID 16910635.

- ^ Petrukhina, M. A. (2008). "Coordination of buckybowls: the first concave-bound metal complex". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 47 (9): 1550–1552. doi:10.1002/anie.200704783. PMID 18214869.

- ^ Zhu, B.; Ellern, A.; Sygula, A.; Sygula, R.; Angelici, R. J. (2007). "η6-Coordination of the Curved Carbon Surface of Corannulene (C20H10) to (η6-arene)M2+(M = Ru, Os)". Organometallics. 26 (7): 1721–1728. doi:10.1021/om0610795.

- ^ Petrukhina, M. A.; Sevryugina, Y.; Rogachev, A. Y.; Jackson, E. A.; Scott, L. T. (2006). "Corannulene: A Preference forexo-Metal Binding. X-ray Structural Characterization of [Ru2(O2CCF3)2(CO)4·(η2-C20H10)2]". Organometallics. 25 (22): 5492–5495. doi:10.1021/om060350f.

- ^ Siegel, J.; Baldridge, K.; Linden, A.; Dorta, R. (2006). "D8 rhodium and iridium complexes of corannulene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (33): 10644–10645. doi:10.1021/ja062110x. PMID 16910635.

- ^ Bandera, D.; Baldridge, K. K.; Linden, A.; Dorta, R.; Siegel, J. S. (2011). "Stereoselective Coordination of C5-Symmetric Corannulene Derivatives with an Enantiomerically Pure [RhI(nbd*)] Metal Complex". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 50 (4): 865–867. doi:10.1002/anie.201006877. PMID 21246679.

- ^ Diana, Nooramalina; Yamada, Yasuhiro; Gohda, Syun; Ono, Hironobu; Kubo, Shingo; Sato, Satoshi (2021-02-01). "Carbon materials with high pentagon density". Journal of Materials Science. 56 (4): 2912–2943. Bibcode:2021JMatS..56.2912D. doi:10.1007/s10853-020-05392-x. ISSN 1573-4803. S2CID 224784081.

![Cyclopenta[bc]corannulene](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/21/Cyclopenta-bc-corannulene.png/100px-Cyclopenta-bc-corannulene.png)