Barred hawk

| Barred hawk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Subfamily: | Buteoninae |

| Genus: | Morphnarchus Ridgway, 1920 |

| Species: | M. princeps

|

| Binomial name | |

| Morphnarchus princeps (Sclater, PL, 1865)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Leucopternis princeps | |

The barred hawk (Morphnarchus princeps) is a species of bird of prey in the family Accipitridae. It has also been known as the black-chested hawk.

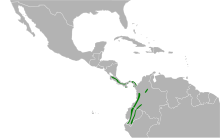

It is found in Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, and Peru. Its natural habitats are subtropical or tropical moist lowland forest and subtropical or tropical moist montane forest. 10,000 to 100,000 barred hawks are thought to exist throughout Central and South America. Barred hawks mainly live in the dense forests of the lowland and mountainous areas.

Taxonomy and evolution

[edit]Philip Sclater first classified the barred hawk in 1865. Barred hawks are in the family Accipitridae that contains all the hawks, eagles, and old world vultures.[2] Recent research-using mtDNA to analyze the phylogeny of this genus has been done. What researchers found was that the black and white plumage of genus Leucopternis has evolved at least twice, and the widespread occurrence of this plumage pattern may result from plumage convergence in forested habitats.[2] In classical taxonomy, the black and white plumage pattern was overemphasized in the grouping of Leucopternis and plumage patterns alone may not be reliable taxonomic markers in this family.[2] Studies suggest placing it in its own genus.

Description

[edit]The barred hawk appears black with a single white tail bar from above. The black barred and white belly and under-wing coverts contrast with the black throat, breast, and wing quills.[3] Barred hawks have a snout-like bill that makes them look like they have a heavy head.[3] Despite being a fairly large hawk, of similar size to a large member of the Buteo genus, its wing spread is relatively smaller than most related largish hawks, which allow them to maneuver through the thick forest canopy easier. Total length is from 51 to 61 cm (20 to 24 in) and wingspan is from 112 to 124 cm (44 to 49 in). M. princeps weighs about 1 kg (2.2 lb)[4][5] The female barred hawk, showing sexual dimorphism, is larger than the males. In wing chord length, males measure about 347–367 mm (13.7–14.4 in) and wing length is 351–388 mm (13.8–15.3 in) in females.[3][6] They have very broad wings and short tail: wingspan is 2.2 times total length of the bird.[6] The body of a barred hawk is dark grey with a white chest. On the chest are uniformly spaced black bars, which is where the hawk gets its name.

The calls of M. princeps include high-pitched screaming or whistling, hoarse "whees", "yips", "dits", and "weeps".[7] Barred hawks are usually noisy when soaring in the sky.

Distribution and habitat

[edit]This species of hawk has a large Extent of Occurrence of 350,000 km2. The barred hawks is primarily a Caribbean species of the middle altitudes,[7] and are found in Costa Rica, Peru, and Panama and on both sides of the Andes in northern Ecuador and western Columbia. Subtropical or tropical lowland and mountain forests are the natural habitat of the barred hawk. They live between 300 and 2,500 m (980 and 8,200 ft) in elevation and are most abundant in the 900 to 1,600 m (3,000 to 5,200 ft) elevation range.

Behavior

[edit]Morphnarchus princeps hunts mostly in the canopy and along mountain forests. The hunting technique of barred hawks contains both active and inactive activities. The hawks can be seen silently sitting on a branch looking for prey or habitually soaring noisily in the sky in a group of two or more.[3] Barred hawks rarely leave the forest region to hunt but may hunt along the edges.[8] They swiftly and quietly fly from branch to branch, when hunting within the forest. When perching they are usually at a mid to low height off the ground and are often on the hunt for slow prey such as frogs, snakes, small mammals and birds, and large insects. Of 104 prey items brought to a nest in Ecuador, 48% consisted of La Bonita caecilians and 35% were various snakes.[9] Further study supports the significance of caecilians, largely subterranean and worm-like but potentially large (exceeding 62 cm (24 in) when taken) amphibians, in this species' diet, especially when recent rainfall appears to draw the prey to the surface of the ground.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ BirdLife International (2020). "Morphnarchus princeps". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22695754A168800132. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22695754A168800132.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Raposo do Amaral, Fabio S., Matthew J. Miller, Luis F. Silveira, Eldredge Bermingham, and Anita Wajntal. "Polyphyly of the hawk genera Leucopternis and Buteogallus (Aves, Accipitridae): multiple habitat shifts during the Neotropical buteonine diversification." BMC Evolutionary Biology 6 (2006).

- ^ a b c d Brown, Leslie and Amadon, Dean (1986) Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World. The Wellfleet Press. ISBN 978-1555214722.

- ^ Chavarría-Duriaux, L., Hille, D. C., & Dean, R. (2018). Birds of Nicaragua: A Field Guide. Cornell University Press.

- ^ del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J., eds. (1994). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-15-6.

- ^ a b Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D. (2001). Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-618-12762-3.

- ^ a b Slud, Paul. The Birds of Costa Rica. New York: American Museum of Natural History, 1964.

- ^ Brown, Leslie. Birds of Prey: Their Biology and Ecology. New York: A&W Publisher, 1956.

- ^ Gelis, R.A.; Greeney, H.F. (2007). "Nesting of barred hawk (Leucopternis princeps) in northeast Ecuador" (PDF). Ornitología Neotropical. 18 (4): 607–612.

- ^ Greeney, H.F.; Gelis, R.A.; Funk, W.C. (2008). "Predation on caecilians (Caecilia orientalis) by barred hawks (Leucopterni sprinceps) depends on rainfall". Herpetological Review. 39 (2): 162–164.