Monarda didyma

| Monarda didyma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Lamiales |

| Family: | Lamiaceae |

| Genus: | Monarda |

| Species: | M. didyma

|

| Binomial name | |

| Monarda didyma | |

| |

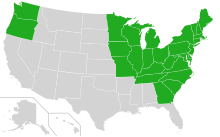

| U.S. distribution of Monarda didyma | |

Monarda didyma, the crimson beebalm, scarlet beebalm, scarlet monarda, Eau-de-Cologne plant, Oswego tea, or bergamot, is a North American aromatic herb in the family Lamiaceae.

Description

[edit]M. didyma is a perennial plant that grows to 0.6–1.2 metres (2–4 feet) in height and spreads 0.4–0.6 m (1+1⁄2–2 ft). The medium to deep green leaves are 7–15 centimetres (3–6 inches) long, shaped ovate to ovate-lanceolate, with serrate margins, placed opposite on square, hollow stems. The leaves are minty fragrant when crushed.[1] The plant's odor is similar to that of the bergamot orange (used to flavor Earl Grey tea).[citation needed]

The bright and red flowers are ragged, tubular and 3–4 cm (1–1+1⁄2 in) long, borne on showy heads of about 30 together, with reddish bracts. It grows in dense clusters along stream banks, moist thickets, and ditches, blooming for about 8 weeks from early to late summer.[1]

-

Visited by a hummingbird

Taxonomy

[edit]The genus name comes from Nicolas Monardes, the first European to describe the American flora, in 1569.[2]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The species is native to eastern North America from Maine west to Ontario and Michigan, and south to northern Georgia, and introduced in other states farther west.[3][4][5]

Ecology

[edit]This plants attracts hummingbirds and is a larval host to the hermit sphinx, raspberry pyrausta, and orange mint moth.[6]

Uses

[edit]Crimson beebalm is extensively grown as an ornamental plant, both within and outside its native range; it is naturalized further west in the United States and also in parts of Europe and Asia. It grows best in full sun, but tolerates light shade and thrives in any moist, but well-drained soil. Several cultivars have been selected for different flower color, ranging from white through pink to dark red and purple.[7]

Beebalm has a long history of use as a medicinal plant by many Native Americans, including the Blackfoot. The Blackfoot people recognized this plant's strong antiseptic action, and used poultices of the plant for skin infections and minor wounds.[8] An herbal tea made from the plant was also used to treat mouth and throat infections caused by dental caries and gingivitis.[citation needed] Beebalm is a natural source of the antiseptic thymol, the primary active ingredient in modern commercial mouthwash formulas.[citation needed] The Winnebago used an herbal tea made from beebalm as a general stimulant.[citation needed] It was also used as a carminative herb by Native Americans to treat excessive flatulence.[9][10] The Native Americans of Oswego, New York, made the leaves into a tea, giving the plant one of its common names.[11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Monarda didyma". Plant Finder. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ "Monarda didyma". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "Monarda didyma". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (WCSP). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

- ^ "Monarda didyma". County-level distribution map from the North American Plant Atlas (NAPA). Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2013.

- ^ USDA, NRCS (n.d.). "Monarda didyma". The PLANTS Database (plants.usda.gov). Greensboro, North Carolina: National Plant Data Team.

- ^ The Xerces Society (2016), Gardening for Butterflies: How You Can Attract and Protect Beautiful, Beneficial Insects, Timber Press.

- ^ Blanchan, Neltje (2005). Wild Flowers Worth Knowing. Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.

- ^ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Midwest Region. "Restoring wildlife habitat and traditional plants with the Oneida Nation".

- ^ Edible and Medicinal Plants of the West, Gregory L. Tilford, ISBN 0-87842-359-1

- ^ Pink, A. (2004). Gardening for the Million. Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.

- ^ Niering, William A.; Olmstead, Nancy C. (1985) [1979]. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Wildflowers, Eastern Region. Knopf. p. 575. ISBN 0-394-50432-1. The Audubon Society.