n-Butyllithium

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

butyllithium, tetra-μ3-butyl-tetralithium

| |

| Other names

NBL, BuLi,

1-lithiobutane | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.363 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| C4H9Li | |

| Molar mass | 64.06 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | colorless crystals unstable usually obtained as soln |

| Density | 0.68 g/cm³, solvent defined |

| Melting point | -76 °C (<273 K) |

| Boiling point | decomposes |

| reacts violently | |

| Solubility in diethyl ether | soluble |

| Acidity (pKa) | >35 (need source) |

| Structure | |

| tetrameric in solution | |

| 0 D | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

inflames in air, decomposes to corrosive LiOH |

| Related compounds | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

n-Butyllithium (abbreviated n-BuLi) is the most prominent organolithium reagent. It enjoys wide use as a polymerisation initiator in the production of elastomers such as polybutadiene or styrene-butadiene-styrene (SBS). Also, it is broadly employed as a strong base (superbase) in organic synthesis, both industrially and in the laboratory.

Butyllithium is commercially available as solutions (15%, 25%, 2 M, 2.5 M, 10 M, etc.) in alkanes such as pentane, hexanes, and heptanes or in ethers as diethyl ether et THF . Annual worldwide production and consumption of butyllithium and other organolithium compounds is estimated at 1800 tonnes.[citation needed]

Although it is a colourless solid, n-butyllithium is usually encountered as a pale yellow solution in alkanes. Such solutions are stable indefinitely if properly stored,[1] but in practice, they degrade upon aging. Fine white precipitate (lithium hydride) is deposited and the color changes to orange.

Structure and bonding

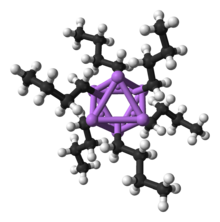

n-BuLi exists as a cluster both in the solid state and in a solution in most solvents. The tendency to aggregate is common for organolithium compounds. The aggregates are held together by delocalized covalent bonds between lithium and the terminal carbon of the butyl chain.[2] In the case of n-BuLi, the clusters are tetrameric (in ether) or hexameric (in cyclohexane). The tetrahedral cluster is a distorted cubane structure with Li and CH2R groups at alternating vertices. An equivalent description describes the tetramer as a Li4 tetrahedron interpenetrated with a tetrahedron [CH2R]4. Bonding within the cluster is related to that used to describe diborane, but more complex since eight atoms are involved. Reflecting its "electron-deficient character," n-butyllithium is highly reactive toward Lewis bases.

Due to the large difference between the electronegativities of carbon (2.55) and lithium (0.98), the C-Li bond is highly polarized. The charge separation has been estimated to be 55-95%. For practical purposes, n-BuLi can often be considered to react as the butyl anion, n-Bu−, and a lithium cation, Li+ even though this model is incorrect: n-BuLi is not ionic.

Preparation

The standard preparation for n-BuLi is reaction of bromobutane or chlorobutane with Li metal:[1]

- 2 Li + C4H9X → C4H9Li + LiX

- where X = Cl, Br

The lithium for this reaction contains 1-3% sodium. Solvents used for this preparation include benzene, cyclohexane, and diethyl ether. When BuBr is the precursor, the product is a homogeneous solution, consisting of a mixed cluster containing both LiBr and Buli. BuLi forms a weaker complex with LiCl, so that the reaction of BuCl with Li produces a precipitate of LiCl.

Reactions

Butyllithium is a strong base (pKa ≈ 40), but it is also a powerful nucleophile and reductant, depending on the other reactants. Furthermore, in addition to being a strong nucleophile, n-BuLi binds to aprotic Lewis bases, such as ethers and tertiary amines, which disagregate the clusters by binding to the lithium centers. Its use as a strong base is referred to as metalation. Reactions are typically conducted in tetrahydrofuran and diethyl ether, which are good solvents for the resulting organolithium derivatives (see below).

Metalation

One of the most useful chemical properties of n-BuLi is its ability to deprotonate a wide range of weak Brønsted acids. t-Butyllithium and s-butyllithium are more basic still. n-BuLi can deprotonate (that is, metalate) many types of C-H bonds, especially where the conjugate base is stabilized by electron delocalization or one or more heteroatoms (non carbon atoms). Examples include acetylenes (H-CC-R), methyl sulfides (H-CH2SR), thioacetals (H-CH(SR)2, e.g. dithiane), methylphosphines (H-CH2PR2), furans, thiophenes and ferrocene (Fe(H-C5H4)(C5H5)).[3] In addition to these, it will also deprotonate all more acidic compounds such as alcohols, amines, enolizable carbonyl compounds, and any overtly acidic compounds, to produce alkoxides, amides, enolates and other -ates of lithium, respectively. The stability and volatility of the butane resulting from such deprotonation reactions is convenient, but can also be a problem for large-scale reactions because of the volume of a flammable gas produced.

- LiC4H9 + R-H → C4H10 + R-Li

The kinetic basicity of n-BuLi is affected by the reaction solvent or cosolvent. Ligands that complex Li+ such as tetrahydrofuran (THF), tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA), hexamethylphosphoramide (HMPA), and 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO) further polarize the Li-C bond and accelerate the metalation. Such additives can also aid in the isolation of the lithiated product, a famous example of which is dilithioferrocene.

- Fe(C5H5)2 + 2 LiC4H9 + 2 TMEDA → 2 C4H10 + Fe(C5H4Li)2(TMEDA)2

Schlosser's base is a superbase produced by treating butyllithium with potassium tert-butoxide. It is kinetically more reactive than butyllithium and is often used to accomplish difficult metalations. The butoxide anion complexes the lithium and effectively produces butylpotassium, which is more reactive than the corresponding lithium reagent.

An example of the use of n-butyllithium as a base is the addition of an amine to methyl carbonate to form a methyl carbamate, where n-butyllithium serves to deprotonate the amine:

- n-BuLi + R2NH + (MeO)2CO → R2N-CO2Me + LiOMe + BuH

Halogen-lithium exchange

Butyllithium reacts with some organic bromides and iodides in an exchange reaction to form the corresponding organolithium derivative. The reaction usually fails with organic chlorides and fluorides:

- C4H9Li + RX → C4H9X + RLi (X = Br, I)

This reaction is a useful method for preparation of several types of RLi compounds, particularly aryllithium and some vinyllithium reagents. The utility of this method is significantly limited, however, by the presence in the reaction mixture of n-BuBr or n-BuI, which can react with the RLi reagent formed, and by competing dehydrohalogenation reactions, in which n-BuLi serves as a base:

- 2C4H9Br + RLi → C4H9R + LiBr

- 2C4H9Li + R'CH=CHBr → C4H10 + R'C≡CLi + LiBr

These side reaction are significantly less important for RI than for RBr, since the iodine-lithium exchange is several orders of magnitude faster than the bromine-lithium exchange. For these reasons, aryl, vinyl and primary alkyl iodides are the preferred substrates, and t-BuLi rather than n-BuLi is usually used, since the formed t-BuI is immediately destroyed by the t-BuLi in a dehydrohalogenation reaction (thus requiring 2 equiv of t-BuLi). Alternatively, vinyl lithium reagents can be generated by direct reaction of the vinyl halide (e.g. cyclohexenyl chloride) with lithium or by tin-lithium exchange (see next section).[1]

Transmetalations

A related family of reactions are the transmetalations, wherein two organometallic compounds exchange their metals. Many examples of such reactions involve Li exchange with Sn:

- C4H9Li + Me3SnAr → C4H9SnMe3 + LiAr

- where Ar is aryl and Me is methyl

The tin-lithium exchange reactions have one major advantage over the halogen-lithium exchanges for the preparation of organolithium reagents, in that the product tin compounds (C4H9SnMe3 in the example above) are much less reactive towards lithium reagents than are the halide products of the corresponding halogen-lithium exchanges (C4H9Br or C4H9I). Other metals and metaloids which undergo such exchange reactions are organic compounds of mercury, selenium, and tellurium.

Carbonyl additions

Organolithium reagents, including n-BuLi are used in synthesis of specific aldehydes and ketones. One such synthetic pathway is the reaction of an organolithium reagent with disubstituted amides:

- R1Li + R2CONMe2 → LiNMe2 + R2C(O)R1

Carbolithiations

Butyllithium will add to certain activated terminal alkenes, such as styrene, butadiene or even ethylene itself to form a new organolithium reagent. This reaction is the basis for the commercially important use of butyllithium for the production of polystyrene and polybutadiene.

- C4H9Li + CH2=CH-C6H5 → C4H9-CH2-CH(Li)-C6H5

Degradation of THF

THF is deprotonated by butyllithium, especially in the presence of TMEDA, by loss of one of four protons adjacent to oxygen. This process, which consumes butyllithium to generate butane, induces a reverse cycloaddition to give enolate of acetaldehyde and ethylene. Therefore, reactions of BuLi in THF are typically conducted at low temperatures, such as –78 °C, as is conveniently produced by a freezing bath of dry ice/acetone. Higher temperatures (-25 °C or even -15 °C) are also used.

Thermal decomposition

When heated, n-BuLi, analogously to other alkyllithium reagents with "β-hydrogens", undergoes β-hydride elimination to produce 1-butene and LiH:

- C4H9Li → LiH + CH3CH2CH=CH2

Safety

It is chemically sensible to store and handle all alkyl-lithiums in sealed systems under inert gas to prevent loss of activity and for reasons of safety. BuLi reacts violently with water:

- C4H9Li + H2O → C4H10 + LiOH

BuLi also reacts with CO2 to give lithium pentanoate:

- C4H9Li + CO2 → C4H9CO2Li

In particular tertiary-butyllithium is extremely reactive towards air and moisture, its hydrolysis being significantly exothermic enough to ignite the solvent (commercial sources typically using tetrahydrofuran, diethyl ether, or hexanes), and thus often inflaming upon exposure to the atmosphere. In some instances it may self-seal, e.g. in needles, preventing further access of oxygen due to hydroxide and oxide barriers being formed. This is analogous to oxide surface layers on the perceived stable metallic form of aluminum. While t-BuLi is classified as being spontaneously pyrophoric in an air atmosphere, n-BuLi is not, but to prevent degradation is still handled under a dry nitrogen atmosphere.

References

- ^ a b c Brandsma, L.; Verkraijsse, H. D. (1987). Preparative Polar Organometallic Chemistry I. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-16916-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Elschenbroich, C. ”Organometallics” (2006) Wiley-VCH: Weinheim. ISBN 978-3-29390-6

- ^ Sanders, R.; Mueller-Westerhoff, U. T. (1996). "The Lithiation of Ferrocene and Ruthenocene - A Retraction and an Improvement". Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 512: 219–224. doi:10.1016/0022-328X(95)05914-B.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

- FMC Lithium manufacturer's product sheets

- Environmental Chemistry directory

- Weissenbacher, Anderson, Ishikawa, Organometallics, July 1998, p681.7002, Chemicals Economics Handbook SRI International

- HPV test plan, submitted by FMC Lithium to EPA

- Ovaska, T. V. e-EROS Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis "n-butyllithium." Wiley and sons. 2006. doi:10.1002/047084289X.rb395

- Greenwood, N. N.; Earnshaw, A. Chemistry of the Elements, 2nd ed. 1997: Butterworth-Heinemann, Boston.