Coronavirus spike protein: Difference between revisions

image |

→COVID-19 response: variants and mutations |

||

| Line 161: | Line 161: | ||

[[File:REGN-COV2 binding SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.png|thumb|right|[[Casirivimab]] (blue) and [[imdevimab]] (orange) interacting with the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein (pink).<ref name="hansen_2020">{{cite journal |last1=Hansen |first1=Johanna |last2=Baum |first2=Alina |last3=Pascal |first3=Kristen E. |last4=Russo |first4=Vincenzo |last5=Giordano |first5=Stephanie |last6=Wloga |first6=Elzbieta |last7=Fulton |first7=Benjamin O. |last8=Yan |first8=Ying |last9=Koon |first9=Katrina |last10=Patel |first10=Krunal |last11=Chung |first11=Kyung Min |last12=Hermann |first12=Aynur |last13=Ullman |first13=Erica |last14=Cruz |first14=Jonathan |last15=Rafique |first15=Ashique |last16=Huang |first16=Tammy |last17=Fairhurst |first17=Jeanette |last18=Libertiny |first18=Christen |last19=Malbec |first19=Marine |last20=Lee |first20=Wen-yi |last21=Welsh |first21=Richard |last22=Farr |first22=Glen |last23=Pennington |first23=Seth |last24=Deshpande |first24=Dipali |last25=Cheng |first25=Jemmie |last26=Watty |first26=Anke |last27=Bouffard |first27=Pascal |last28=Babb |first28=Robert |last29=Levenkova |first29=Natasha |last30=Chen |first30=Calvin |last31=Zhang |first31=Bojie |last32=Romero Hernandez |first32=Annabel |last33=Saotome |first33=Kei |last34=Zhou |first34=Yi |last35=Franklin |first35=Matthew |last36=Sivapalasingam |first36=Sumathi |last37=Lye |first37=David Chien |last38=Weston |first38=Stuart |last39=Logue |first39=James |last40=Haupt |first40=Robert |last41=Frieman |first41=Matthew |last42=Chen |first42=Gang |last43=Olson |first43=William |last44=Murphy |first44=Andrew J. |last45=Stahl |first45=Neil |last46=Yancopoulos |first46=George D. |last47=Kyratsous |first47=Christos A. |title=Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail |journal=Science |date=21 August 2020 |volume=369 |issue=6506 |pages=1010–1014 |doi=10.1126/science.abd0827|pmc=7299284 }}</ref><ref name="wrapp_2020">{{cite journal |last1=Wrapp |first1=Daniel |last2=Wang |first2=Nianshuang |last3=Corbett |first3=Kizzmekia S. |last4=Goldsmith |first4=Jory A. |last5=Hsieh |first5=Ching-Lin |last6=Abiona |first6=Olubukola |last7=Graham |first7=Barney S. |last8=McLellan |first8=Jason S. |title=Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation |journal=Science |date=13 March 2020 |volume=367 |issue=6483 |pages=1260–1263 |doi=10.1126/science.abb2507|pmc=7164637 }}</ref>]] |

[[File:REGN-COV2 binding SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.png|thumb|right|[[Casirivimab]] (blue) and [[imdevimab]] (orange) interacting with the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein (pink).<ref name="hansen_2020">{{cite journal |last1=Hansen |first1=Johanna |last2=Baum |first2=Alina |last3=Pascal |first3=Kristen E. |last4=Russo |first4=Vincenzo |last5=Giordano |first5=Stephanie |last6=Wloga |first6=Elzbieta |last7=Fulton |first7=Benjamin O. |last8=Yan |first8=Ying |last9=Koon |first9=Katrina |last10=Patel |first10=Krunal |last11=Chung |first11=Kyung Min |last12=Hermann |first12=Aynur |last13=Ullman |first13=Erica |last14=Cruz |first14=Jonathan |last15=Rafique |first15=Ashique |last16=Huang |first16=Tammy |last17=Fairhurst |first17=Jeanette |last18=Libertiny |first18=Christen |last19=Malbec |first19=Marine |last20=Lee |first20=Wen-yi |last21=Welsh |first21=Richard |last22=Farr |first22=Glen |last23=Pennington |first23=Seth |last24=Deshpande |first24=Dipali |last25=Cheng |first25=Jemmie |last26=Watty |first26=Anke |last27=Bouffard |first27=Pascal |last28=Babb |first28=Robert |last29=Levenkova |first29=Natasha |last30=Chen |first30=Calvin |last31=Zhang |first31=Bojie |last32=Romero Hernandez |first32=Annabel |last33=Saotome |first33=Kei |last34=Zhou |first34=Yi |last35=Franklin |first35=Matthew |last36=Sivapalasingam |first36=Sumathi |last37=Lye |first37=David Chien |last38=Weston |first38=Stuart |last39=Logue |first39=James |last40=Haupt |first40=Robert |last41=Frieman |first41=Matthew |last42=Chen |first42=Gang |last43=Olson |first43=William |last44=Murphy |first44=Andrew J. |last45=Stahl |first45=Neil |last46=Yancopoulos |first46=George D. |last47=Kyratsous |first47=Christos A. |title=Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail |journal=Science |date=21 August 2020 |volume=369 |issue=6506 |pages=1010–1014 |doi=10.1126/science.abd0827|pmc=7299284 }}</ref><ref name="wrapp_2020">{{cite journal |last1=Wrapp |first1=Daniel |last2=Wang |first2=Nianshuang |last3=Corbett |first3=Kizzmekia S. |last4=Goldsmith |first4=Jory A. |last5=Hsieh |first5=Ching-Lin |last6=Abiona |first6=Olubukola |last7=Graham |first7=Barney S. |last8=McLellan |first8=Jason S. |title=Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation |journal=Science |date=13 March 2020 |volume=367 |issue=6483 |pages=1260–1263 |doi=10.1126/science.abb2507|pmc=7164637 }}</ref>]] |

||

[[Monoclonal antibodies]] that target the spike protein have been developed as [[Covid-19 treatment]]s. As of July 8, 2021, three monoclonal antibody products had received [[Emergency Use Authorization]] in the United States:<ref name="nih">{{cite web |title=Therapeutic Management of Nonhospitalized Adults With COVID-19 |url=https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/management/clinical-management/nonhospitalized-adults--therapeutic-management/https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/management/clinical-management/nonhospitalized-adults--therapeutic-management/ |website=Covid-19 Treatment Guidelines |publisher=National Institutes of Health}}</ref> [[bamlanivimab/etesevimab]],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=11331|title=etesevimab|website=IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology|accessdate=2021-02-10}}</ref><ref name="Lilly PR 2020-10-28">{{cite press release|title=Lilly announces agreement with U.S. government to supply 300,000 vials of investigational neutralizing antibody bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) in an effort to fight COVID-19|url=https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lilly-announces-agreement-us-government-supply-300000-vials|website=Eli Lilly and Company|date=October 28, 2020 }}</ref> [[casirivimab/imdevimab]],<ref name="REGEN-COV FDA label">{{cite web | title=Casirivimab injection, solution, concentrate Imdevimab injection, solution, concentrate REGEN-COV- casirivimab and imdevimab kit | website=DailyMed | url=https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=f5bf7a31-7e17-4a94-805c-d231ea458fb0 | access-date=18 March 2021}}</ref> and [[sotrovimab]].<ref name="Sotrovimab FDA label">{{cite web | title=Sotrovimab injection, solution, concentrate | website=DailyMed | url=https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=aa5cca2e-4351-4f81-b0e5-3303ac0b2474 | access-date=15 June 2021}}</ref> Bamlanivimab/etesevimab was not recommended in the United States due to the increase in [[SARS-CoV-2 variant]]s that are less susceptible to these antibodies.<ref name=nih /> |

[[Monoclonal antibodies]] that target the spike protein have been developed as [[Covid-19 treatment]]s. As of July 8, 2021, three monoclonal antibody products had received [[Emergency Use Authorization]] in the United States:<ref name="nih">{{cite web |title=Therapeutic Management of Nonhospitalized Adults With COVID-19 |url=https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/management/clinical-management/nonhospitalized-adults--therapeutic-management/https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/management/clinical-management/nonhospitalized-adults--therapeutic-management/ |website=Covid-19 Treatment Guidelines |publisher=National Institutes of Health}}</ref> [[bamlanivimab/etesevimab]],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/LigandDisplayForward?ligandId=11331|title=etesevimab|website=IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology|accessdate=2021-02-10}}</ref><ref name="Lilly PR 2020-10-28">{{cite press release|title=Lilly announces agreement with U.S. government to supply 300,000 vials of investigational neutralizing antibody bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) in an effort to fight COVID-19|url=https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/lilly-announces-agreement-us-government-supply-300000-vials|website=Eli Lilly and Company|date=October 28, 2020 }}</ref> [[casirivimab/imdevimab]],<ref name="REGEN-COV FDA label">{{cite web | title=Casirivimab injection, solution, concentrate Imdevimab injection, solution, concentrate REGEN-COV- casirivimab and imdevimab kit | website=DailyMed | url=https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=f5bf7a31-7e17-4a94-805c-d231ea458fb0 | access-date=18 March 2021}}</ref> and [[sotrovimab]].<ref name="Sotrovimab FDA label">{{cite web | title=Sotrovimab injection, solution, concentrate | website=DailyMed | url=https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=aa5cca2e-4351-4f81-b0e5-3303ac0b2474 | access-date=15 June 2021}}</ref> Bamlanivimab/etesevimab was not recommended in the United States due to the increase in [[SARS-CoV-2 variant]]s that are less susceptible to these antibodies.<ref name=nih /> |

||

===SARS-CoV-2 variants=== |

|||

{{main|Variants of SARS-CoV-2}} |

|||

Throughout the [[COVID-19 pandemic]], the [[genome]] of SARS-CoV-2 viruses was [[sequenced]] many times, resulting in identification of thousands of distinct [[variant (biology)|variants]].<ref name="koyama_2020">{{cite journal |last1=Koyama |first1=Takahiko |last2=Platt |first2=Daniel |last3=Parida |first3=Laxmi |title=Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes |journal=Bulletin of the World Health Organization |date=1 July 2020 |volume=98 |issue=7 |pages=495–504 |doi=10.2471/BLT.20.253591}}</ref> Many of these possess [[mutation]]s that change the [[amino acid]] [[protein sequence|sequence]] of the spike protein. In a [[World Health Organization]] analysis from July 2020, the spike (''S'') gene was the second most frequently mutated in the genome, after ''ORF1ab'' (which encodes most of the virus' [[viral nonstructural protein|nonstructural protein]]s).<ref name=koyama_2020 /> The [[evolution rate]] in the spike gene is higher than that observed in the genome overall.<ref name="winger_2021">{{cite journal |last1=Winger |first1=Anna |last2=Caspari |first2=Thomas |title=The Spike of Concern—The Novel Variants of SARS-CoV-2 |journal=Viruses |date=27 May 2021 |volume=13 |issue=6 |pages=1002 |doi=10.3390/v13061002}}</ref> Analyses of SARS-CoV-2 genomes suggests that some sites in the spike protein sequence, particularly in the receptor-binding domain, are of evolutionary importance<ref name="saputri_2020">{{cite journal |last1=Saputri |first1=Dianita S. |last2=Li |first2=Songling |last3=van Eerden |first3=Floris J. |last4=Rozewicki |first4=John |last5=Xu |first5=Zichang |last6=Ismanto |first6=Hendra S. |last7=Davila |first7=Ana |last8=Teraguchi |first8=Shunsuke |last9=Katoh |first9=Kazutaka |last10=Standley |first10=Daron M. |title=Flexible, Functional, and Familiar: Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Evolution |journal=Frontiers in Microbiology |date=17 September 2020 |volume=11 |pages=2112 |doi=10.3389/fmicb.2020.02112}}</ref> and are undergoing [[positive selection]].<ref name="cagliani_2020">{{cite journal |last1=Cagliani |first1=Rachele |last2=Forni |first2=Diego |last3=Clerici |first3=Mario |last4=Sironi |first4=Manuela |title=Computational Inference of Selection Underlying the Evolution of the Novel Coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |journal=Journal of Virology |date=June 2020 |volume=94 |issue=12 |doi=10.1128/JVI.00411-20}}</ref><ref name="harvey_2021">{{cite journal |last1=Harvey |first1=William T. |last2=Carabelli |first2=Alessandro M. |last3=Jackson |first3=Ben |last4=Gupta |first4=Ravindra K. |last5=Thomson |first5=Emma C. |last6=Harrison |first6=Ewan M. |last7=Ludden |first7=Catherine |last8=Reeve |first8=Richard |last9=Rambaut |first9=Andrew |last10=Peacock |first10=Sharon J. |last11=Robertson |first11=David L. |title=SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape |journal=Nature Reviews Microbiology |date=July 2021 |volume=19 |issue=7 |pages=409–424 |doi=10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0}}</ref> |

|||

Spike protein mutations raise concern because they may affect [[infectivity]] or [[transmission (medicine)|transmissibility]], or facilitate [[immune escape]].<ref name=harvey_2021 /> The mutation [[aspartate|D]]614[[glycine|G]] has arisen independently in multiple viral lineages and become dominant among sequenced genomes;<ref name="isabel_2020">{{cite journal |last1=Isabel |first1=Sandra |last2=Graña-Miraglia |first2=Lucía |last3=Gutierrez |first3=Jahir M. |last4=Bundalovic-Torma |first4=Cedoljub |last5=Groves |first5=Helen E. |last6=Isabel |first6=Marc R. |last7=Eshaghi |first7=AliReza |last8=Patel |first8=Samir N. |last9=Gubbay |first9=Jonathan B. |last10=Poutanen |first10=Tomi |last11=Guttman |first11=David S. |last12=Poutanen |first12=Susan M. |title=Evolutionary and structural analyses of SARS-CoV-2 D614G spike protein mutation now documented worldwide |journal=Scientific Reports |date=December 2020 |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=14031 |doi=10.1038/s41598-020-70827-z}}</ref><ref name="korber_2020">{{cite journal |last1=Korber |first1=Bette |last2=Fischer |first2=Will M. |last3=Gnanakaran |first3=Sandrasegaram |last4=Yoon |first4=Hyejin |last5=Theiler |first5=James |last6=Abfalterer |first6=Werner |last7=Hengartner |first7=Nick |last8=Giorgi |first8=Elena E. |last9=Bhattacharya |first9=Tanmoy |last10=Foley |first10=Brian |last11=Hastie |first11=Kathryn M. |last12=Parker |first12=Matthew D. |last13=Partridge |first13=David G. |last14=Evans |first14=Cariad M. |last15=Freeman |first15=Timothy M. |last16=de Silva |first16=Thushan I. |last17=McDanal |first17=Charlene |last18=Perez |first18=Lautaro G. |last19=Tang |first19=Haili |last20=Moon-Walker |first20=Alex |last21=Whelan |first21=Sean P. |last22=LaBranche |first22=Celia C. |last23=Saphire |first23=Erica O. |last24=Montefiori |first24=David C. |last25=Angyal |first25=Adrienne |last26=Brown |first26=Rebecca L. |last27=Carrilero |first27=Laura |last28=Green |first28=Luke R. |last29=Groves |first29=Danielle C. |last30=Johnson |first30=Katie J. |last31=Keeley |first31=Alexander J. |last32=Lindsey |first32=Benjamin B. |last33=Parsons |first33=Paul J. |last34=Raza |first34=Mohammad |last35=Rowland-Jones |first35=Sarah |last36=Smith |first36=Nikki |last37=Tucker |first37=Rachel M. |last38=Wang |first38=Dennis |last39=Wyles |first39=Matthew D. |title=Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus |journal=Cell |date=August 2020 |volume=182 |issue=4 |pages=812–827.e19 |doi=10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043}}</ref> it may have advantages in infectivity and transmissibility<ref name=harvey_2021 /> possibly due to increasing the density of spikes on the viral surface,<ref name="zhang_2020">{{cite journal |last1=Zhang |first1=Lizhou |last2=Jackson |first2=Cody B. |last3=Mou |first3=Huihui |last4=Ojha |first4=Amrita |last5=Peng |first5=Haiyong |last6=Quinlan |first6=Brian D. |last7=Rangarajan |first7=Erumbi S. |last8=Pan |first8=Andi |last9=Vanderheiden |first9=Abigail |last10=Suthar |first10=Mehul S. |last11=Li |first11=Wenhui |last12=Izard |first12=Tina |last13=Rader |first13=Christoph |last14=Farzan |first14=Michael |last15=Choe |first15=Hyeryun |title=SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein D614G mutation increases virion spike density and infectivity |journal=Nature Communications |date=December 2020 |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=6013 |doi=10.1038/s41467-020-19808-4}}</ref> increasing the proportion of binding-competent conformations, or improving stability.<ref name="jackson_2021">{{cite journal |last1=Jackson |first1=Cody B. |last2=Zhang |first2=Lizhou |last3=Farzan |first3=Michael |last4=Choe |first4=Hyeryun |title=Functional importance of the D614G mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein |journal=Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications |date=January 2021 |volume=538 |pages=108–115 |doi=10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.11.026}}</ref> Mutations at position [[glutamate|E]]484, particularly [[glutamate|E]]484[[arginine|K]], have been associated with [[immune escape]] and reduced [[antibody]] binding.<ref name=harvey_2021 /><ref name=winger_2021 /> |

|||

===Misinformation=== |

===Misinformation=== |

||

Revision as of 05:49, 29 August 2021

| Coronavirus spike glycoprotein S1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Model of the external structure of the SARS-CoV-2 virion.[1]

● Blue: envelope ● Turquoise: spike glycoprotein (S) ● Red: envelope proteins (E) ● Green: membrane proteins (M) ● Orange: glycan | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | CoV_S1 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01600 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR002551 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Coronavirus spike glycoprotein S2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | CoV_S2 | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01601 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR002552 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Betacoronavirus spike glycoprotein S1, receptor binding | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | bCoV_S1_RBD | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09408 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR018548 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Betacoronavirus-like spike glycoprotein S1, N-terminal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | bCoV_S1_N | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF16451 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR032500 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Spike (S) protein (sometimes also spike glycoprotein,[2] formerly known as E2[3]) is the largest of the four major structural proteins found in coronaviruses.[4] The spike protein assembles into trimers that form large structures, called spikes or peplomers,[3] that project from the surface of the virion.[4][5] The distinctive appearance of these spikes when visualized using negative stain transmission electron microscopy, "recalling the solar corona",[6] gives the virus family its name.[2]

The function of the spike protein is to mediate viral entry into the host cell by first interacting with molecules on the exterior cell surface and then fusing the viral and cellular membranes. The spike protein is a class I fusion protein that contains two regions, known as S1 and S2, responsible for these two functions. The S1 region contains the receptor-binding domain that binds to receptors on the cell surface. Coronaviruses use a very diverse range of receptors; SARS-CoV (which causes SARS) and SARS-CoV-2 (which causes Covid-19) both interact with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). The S2 region contains the fusion peptide and other fusion infrastructure necessary for membrane fusion with the host cell, a required step for infection and viral replication. The spike protein determines the virus' host range (which organisms it can infect) and cell tropism (which cells or tissues it can infect within an organism).[4][5][7][8]

The spike protein is highly immunogenic. Antibodies against the spike protein are found in patients recovered from SARS and COVID-19. Neutralizing antibodies target epitopes on the receptor-binding domain.[9] Most Covid-19 vaccine development efforts in response to the Covid-19 pandemic aim to activate the immune system against the spike protein.[10][11][12]

Structure

The spike protein is very large, often 1200-1400 amino acid residues long;[8] it is 1273 residues in SARS-CoV-2.[5] It is a single-pass transmembrane protein with a short C-terminal tail on the interior of the virus, a transmembrane helix, and a large N-terminal ectodomain exposed on the virus exterior.[7][5]

The spike protein forms homotrimers in which three copies of the protein interact through their ectodomains.[7][5] The trimer structures have been described as club- pear-, or petal-shaped.[3] Each spike protein contains two regions known as S1 and S2, and in the assembled trimer the S1 regions at the N-terminal end form the portion of the protein furthest from the viral surface while the S2 regions form a flexible "stalk" containing most of the protein-protein interactions that hold the trimer in place.[7]

S1

The S1 region of the spike protein is responsible for interacting with receptor molecules on the surface of the host cell in the first step of viral entry.[7][4] S1 contains two domains, called the N-terminal domain (NTD) and C-terminal domain (CTD),[7][2] sometimes also known as the A and B domains.[14] Depending on the coronavirus, either or both domains may be used as receptor-binding domains (RBD). Target receptors can be very diverse, including cell surface receptor proteins and sugars such as sialic acids as receptors or coreceptors.[7][2] In general, the NTD binds sugar molecules while the CTD binds proteins, with the exception of mouse hepatitis virus which uses its NTD to interact with a protein receptor called CEACAM1.[7] The NTD has a galectin-like protein fold, but binds sugar molecules somewhat differently than galectins.[7]

The CTD is responsible for the interactions of MERS-CoV with its receptor dipeptidyl peptidase-4,[7] and those of SARS-CoV[7] and SARS-CoV-2[5] with their receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). The CTD of these viruses can be further divided into two subdomains, known as the core and the extended loop or receptor-binding motif (RBM), where most of the residues that directly contact the target receptor are located.[7][5] There are subtle differences, mainly in the RBM, between the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins' interactions with ACE2.[5] Comparisons of spike proteins from multiple coronaviruses suggest that divergence in the RBM region can account for differences in target receptors, even when the core of the S1 CTD is structurally very similar.[7]

Within coronavirus lineages, as well as across the four major coronavirus subgroups, the S1 region is less well conserved than S2, as befits its role in interacting with virus-specific host cell receptors.[7][4][5] Within the S1 region, the NTD is more highly conserved than the CTD.[7]

S2

The S2 region of the spike protein is responsible for membrane fusion between the viral envelope and the host cell, enabling entry of the virus' genome into the cell.[7][8][5] The S2 region contains the fusion peptide, a stretch of mostly hydrophobic amino acids whose function is to enter and destabilize the host cell membrane.[8][5] S2 also contains two heptad repeat subdomains known as HR1 and HR2, sometimes called the "fusion core" region.[5] These subdomains undergo dramatic conformational changes during the fusion process to form a six-helix bundle, a characteristic feature of the class I fusion proteins.[8][5] The S2 region is also considered to include the transmembrane helix and C-terminal tail located in the interior of the virion.[5]

Relative to S1, the S2 region is very well conserved among coronaviruses.[7][5]

Post-translational modifications

The spike protein is a glycoprotein and is heavily glycosylated through N-linked glycosylation.[4] Studies of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein have also reported O-linked glycosylation in the S1 region.[17] The C-terminal tail, located in the interior of the virion, is enriched in cysteine residues and is palmitoylated.[5][18]

Spike proteins are activated through proteolytic cleavage. They are cleaved by host cell proteases at the S1-S2 boundary and later at what is known as the S2' site at the N-terminus of the fusion peptide.[7][4][5][8]

Conformational change

Like other class I fusion proteins, the spike protein undergoes a very large conformational change during the fusion process.[7][4][5][8] Both the pre-fusion and post-fusion states of several coronaviruses, especially SARS-CoV-2, have been studied by cryo-electron microscopy.[5][19][20][21] Functionally important protein dynamics have also been observed within the pre-fusion state, in which the relative orientations of some of the S1 regions relative to S2 in a trimer can vary. In the closed state, all three S1 regions are packed closely and the region that makes contact with host cell receptors is sterically inaccessible, while the open states have one or two S1 RBDs more accessible for receptor binding, in an open or "up" conformation.[5]

Expression and localization

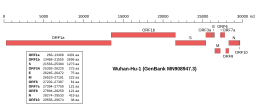

Genomic organisation of isolate Wuhan-Hu-1, the earliest sequenced sample of SARS-CoV-2, indicating the location of the S gene | |

| NCBI genome ID | 86693 |

|---|---|

| Genome size | 29,903 bases |

| Year of completion | 2020 |

| Genome browser (UCSC) | |

The gene encoding the spike protein is located toward the 3' end of the virus's positive-sense RNA genome, along with the genes for the other three structural proteins and various virus-specific accessory proteins.[4][5] Protein trafficking of spike proteins appears to depend on the coronavirus subgroup: when expressed in isolation without other viral proteins, spike proteins from betacoronaviruses are able to reach the cell surface, while those from alphacoronaviruses and gammacoronaviruses are retained intracellularly. In the presence of the M protein, spike protein trafficking is altered and instead is retained at the ERGIC, the site at which viral assembly occurs.[18] In SARS-CoV-2, both the M and the E protein modulate spike protein trafficking through different mechanisms.[22]

The spike protein is not required for viral assembly or the formation of virus-like particles;[18] however, presence of spike may influence the size of the envelope.[23] Incorporation of the spike protein into virions during assembly and budding is dependent on protein-protein interactions with the M protein through the C-terminal tail.[18][22] Examination of virions using cryo-electron microscopy suggests that there are approximately 25[24] to 100 spike trimers per virion.[23][20]

Function

The spike protein is responsible for viral entry into the host cell, a required early step in viral replication. It is essential for replication.[2] It performs this function in two steps, first binding to a receptor on the surface of the host cell through interactions with the S1 region, and then fusing the viral and cellular membranes through the action of the S2 region.[7][8][9] The location of fusion varies depending on the specific coronavirus, with some able to enter at the plasma membrane and others entering from endosomes after endocytosis.[8]

Attachment

The interaction of the receptor-binding domain in the S1 region with its target receptor on the cell surface initiates the process of viral entry. Different coronaviruses target different cell-surface receptors, sometimes using sugar molecules such as sialic acids, or forming protein-protein interactions with proteins exposed on the cell surface.[7][9] Different coronaviruses vary widely in their target receptor. The presence of a target receptor that S1 can bind is a determinant of host range and cell tropism.[7][9][25]

Proteolytic cleavage

Proteolytic cleavage of the spike protein, sometimes known as "priming", is required for membrane fusion. Relative to other class I fusion proteins, this process is complex and requires two cleavages at different sites, one at the S1/S2 boundary and one at the S2' site to release the fusion peptide.[7][5][9] Coronaviruses vary in which part of the viral life cycle these cleavages occur, particularly the S1/S2 cleavage. Many coronaviruses are cleaved at S1/S2 before viral exit from the virus-producing cell, by furin and other proprotein convertases;[7] in SARS-CoV-2 a polybasic furin cleavage site is present at this position.[5][9] Others may be cleaved by extracellular proteases such as elastase, by proteases located on the cell surface after receptor binding, or by proteases found in lysosomes after endocytosis.[7] The specific proteases responsible for this cleavage depends on the virus, cell type, and local environment.[8] In SARS-CoV, the serine protease TMPRSS2 is important for this process, with additional contributions from cysteine proteases cathepsin B and cathepsin L in endosomes.[8][9] Trypsin and trypsin-like proteases have also been reported to contribute.[8] In SARS-CoV-2, TMPRSS2 is the primary protease for S2' cleavage, and its presence is reported to be essential for viral infection.[5][9]

Membrane fusion

Like other class I fusion proteins, the spike protein in its pre-fusion conformation is in a metastable state.[7] A dramatic conformational change is triggered to induce the heptad repeats in the S2 region to refold into an extended six-helix bundle, causing the fusion peptide to interact with the cell membrane and bringing the viral and cell membranes into close proximity.[7][5] Receptor binding and proteolytic cleavage (sometimes known as "priming") are required, but additional triggers for this conformational change vary depending on the coronavirus and local environment.[32] In vitro studies of SARS-CoV suggest a dependence on calcium concentration.[8] Unusually for coronaviruses, infectious bronchitis virus, which infects birds, can be triggered by low pH alone; for other coronaviruses, low pH is not itself a trigger but may be required for activity of proteases, which in turn are required for fusion.[8][32] Variation in the location of membrane fusion - at the plasma membrane or in endosomes - may vary based on the availability of these triggers for conformational change.[32] Fusion of the viral and cell membranes permits the entry of the virus' positive-sense RNA genome into the host cell cytosol, after which expression of viral proteins begins.[4][2][9]

Immunogenicity

Because it is exposed on the surface of the virus, the spike protein is a major antigen to which neutralizing antibodies are developed.[2][9] Its extensive glycosylation can serve as a glycan shield that hides epitopes from the immune system.[9][16] Due to the outbreak of SARS and the Covid-19 pandemic, antibodies to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins have been extensively studied. Antibodies to the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins have been identified that target epitopes on the receptor-binding domain[9][33] or interfere with the process of conformational change.[9] The majority of antibodies from infected individuals target the receptor-binding domain.[34]

COVID-19 response

Vaccines

In response to the Covid-19 pandemic, a number of Covid-19 vaccines have been developed using a variety of technologies, including mRNA vaccines and viral vector vaccines. Most vaccine development has targeted the spike protein.[10][11][12] Building on techniques previously used in vaccine research aimed at respiratory syncytial virus and SARS-CoV, many SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development efforts have used constructs that include mutations to stabilize the spike protein's pre-fusion conformation, facilitating development of antibodies against epitopes exposed in this conformation.[35][36]

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies that target the spike protein have been developed as Covid-19 treatments. As of July 8, 2021, three monoclonal antibody products had received Emergency Use Authorization in the United States:[38] bamlanivimab/etesevimab,[39][40] casirivimab/imdevimab,[41] and sotrovimab.[42] Bamlanivimab/etesevimab was not recommended in the United States due to the increase in SARS-CoV-2 variants that are less susceptible to these antibodies.[38]

SARS-CoV-2 variants

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the genome of SARS-CoV-2 viruses was sequenced many times, resulting in identification of thousands of distinct variants.[43] Many of these possess mutations that change the amino acid sequence of the spike protein. In a World Health Organization analysis from July 2020, the spike (S) gene was the second most frequently mutated in the genome, after ORF1ab (which encodes most of the virus' nonstructural proteins).[43] The evolution rate in the spike gene is higher than that observed in the genome overall.[44] Analyses of SARS-CoV-2 genomes suggests that some sites in the spike protein sequence, particularly in the receptor-binding domain, are of evolutionary importance[45] and are undergoing positive selection.[46][34]

Spike protein mutations raise concern because they may affect infectivity or transmissibility, or facilitate immune escape.[34] The mutation D614G has arisen independently in multiple viral lineages and become dominant among sequenced genomes;[47][48] it may have advantages in infectivity and transmissibility[34] possibly due to increasing the density of spikes on the viral surface,[49] increasing the proportion of binding-competent conformations, or improving stability.[50] Mutations at position E484, particularly E484K, have been associated with immune escape and reduced antibody binding.[34][44]

Misinformation

During the COVID-19 pandemic, anti-vaccination misinformation about COVID-19 circulated on social media platforms related to the spike protein's role in COVID-19 vaccines. Spike proteins were said to be dangerously "cytotoxic" and mRNA vaccines containing them therefore in themselves dangerous. Spike proteins are not cytotoxic or dangerous.[51][52] Spike proteins were also said to be "shed" by vaccinated people, in an erroneous allusion to the phenomenon of vaccine-induced viral shedding, which is a rare effect of live-virus vaccines unlike those used for COVID-19. "Shedding" of spike proteins is not possible.[53][54]

Evolution and conservation

The class I fusion proteins - a group whose well-characterized examples include the coronavirus spike protein as well as influenza virus hemagglutinin and HIV Gp41 - are thought to be evolutionarily related.[7][55] The S2 region of the spike protein responsible for membrane fusion is more highly conserved than the S1 region responsible for receptor interactions.[7][4][5] The S1 region appears to have undergone significant diversifying selection.[56]

Within the S1 region, the N-terminal domain is more conserved than the C-terminal domain.[7] The NTD's galectin-like protein fold suggests a relationship with structurally similar cellular proteins from which it may have evolved through gene capture from the host.[7] It has been suggested that the CTD may have evolved from the NTD by gene duplication.[7] The surface-exposed position of the CTD, vulnerable to the host immune system, may place this region under high selective pressure.[7] Comparisons of the structures of different coronavirus CTDs suggests they may be under diversifying selection[57] and in some cases, distantly related coronaviruses that use the same cell-surface receptor may do so through convergent evolution.[14]

References

- ^ Solodovnikov, Alexey; Arkhipova, Valeria (29 July 2021). "Достоверно красиво: как мы сделали 3D-модель SARS-CoV-2" [Truly beautiful: how we made the SARS-CoV-2 3D model] (in Russian). N+1. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Deng, X.; Baker, S.C. (2021). "Coronaviruses: Molecular Biology (Coronaviridae)". Encyclopedia of Virology: 198–207. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-814515-9.02550-9.

- ^ a b c Masters, Paul S. (2006). "The Molecular Biology of Coronaviruses". Advances in Virus Research. 66: 193–292. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. PMC 7112330.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Wang, Yuhang; Grunewald, Matthew; Perlman, Stanley (2020). "Coronaviruses: An Updated Overview of Their Replication and Pathogenesis". Coronaviruses. 2203: 1–29. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0900-2_1. PMC 7682345.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Zhu, Chaogeng; He, Guiyun; Yin, Qinqin; Zeng, Lin; Ye, Xiangli; Shi, Yongzhong; Xu, Wei (14 June 2021). "Molecular biology of the SARs‐CoV‐2 spike protein: A review of current knowledge". Journal of Medical Virology: jmv.27132. doi:10.1002/jmv.27132.

- ^ "Virology: Coronaviruses". Nature. 220 (5168): 650–650. November 1968. doi:10.1038/220650b0. PMC 7086490.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Li, Fang (29 September 2016). "Structure, Function, and Evolution of Coronavirus Spike Proteins". Annual Review of Virology. 3 (1): 237–261. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301. PMC 5457962.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Millet, Jean Kaoru; Whittaker, Gary R. (April 2018). "Physiological and molecular triggers for SARS-CoV membrane fusion and entry into host cells". Virology. 517: 3–8. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2017.12.015. PMC 7112017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n V’kovski, Philip; Kratzel, Annika; Steiner, Silvio; Stalder, Hanspeter; Thiel, Volker (March 2021). "Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 19 (3): 155–170. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. PMC 7592455.

- ^ a b Flanagan, Katie L.; Best, Emma; Crawford, Nigel W.; Giles, Michelle; Koirala, Archana; Macartney, Kristine; Russell, Fiona; Teh, Benjamin W.; Wen, Sophie CH (2 October 2020). "Progress and Pitfalls in the Quest for Effective SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Vaccines". Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 579250. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.579250. hdl:11343/251733.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Le, Tung Thanh; Cramer, Jakob P.; Chen, Robert; Mayhew, Stephen (October 2020). "Evolution of the COVID-19 vaccine development landscape". Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 19 (10): 667–668. doi:10.1038/d41573-020-00151-8.

- ^ a b Kyriakidis, Nikolaos C.; López-Cortés, Andrés; González, Eduardo Vásconez; Grimaldos, Alejandra Barreto; Prado, Esteban Ortiz (December 2021). "SARS-CoV-2 vaccines strategies: a comprehensive review of phase 3 candidates". npj Vaccines. 6 (1): 28. doi:10.1038/s41541-021-00292-w. PMC 7900244.

- ^ a b Wrapp, Daniel; Wang, Nianshuang; Corbett, Kizzmekia S.; Goldsmith, Jory A.; Hsieh, Ching-Lin; Abiona, Olubukola; Graham, Barney S.; McLellan, Jason S. (13 March 2020). "Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation". Science. 367 (6483): 1260–1263. doi:10.1126/science.abb2507. PMC 7164637.

- ^ a b Hulswit, R.J.G.; de Haan, C.A.M.; Bosch, B.-J. (2016). "Coronavirus Spike Protein and Tropism Changes". Advances in Virus Research. 96: 29–57. doi:10.1016/bs.aivir.2016.08.004. PMC 7112277.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (9 October 2020). "The Coronavirus Unveiled". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ a b Casalino, Lorenzo; Gaieb, Zied; Goldsmith, Jory A.; Hjorth, Christy K.; Dommer, Abigail C.; Harbison, Aoife M.; Fogarty, Carl A.; Barros, Emilia P.; Taylor, Bryn C.; McLellan, Jason S.; Fadda, Elisa; Amaro, Rommie E. (28 October 2020). "Beyond Shielding: The Roles of Glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein". ACS Central Science. 6 (10): 1722–1734. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.0c01056. PMC 7523240.

- ^ Shajahan, Asif; Supekar, Nitin T; Gleinich, Anne S; Azadi, Parastoo (9 December 2020). "Deducing the N- and O-glycosylation profile of the spike protein of novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2". Glycobiology. 30 (12): 981–988. doi:10.1093/glycob/cwaa042. PMC 7239183.

- ^ a b c d Ujike, Makoto; Taguchi, Fumihiro (3 April 2015). "Incorporation of Spike and Membrane Glycoproteins into Coronavirus Virions". Viruses. 7 (4): 1700–1725. doi:10.3390/v7041700. PMC 4411675.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Walls, Alexandra C.; Park, Young-Jun; Tortorici, M. Alejandra; Wall, Abigail; McGuire, Andrew T.; Veesler, David (April 2020). "Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein". Cell. 181 (2): 281–292.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. PMC 7102599.

- ^ a b Klein, Steffen; Cortese, Mirko; Winter, Sophie L.; Wachsmuth-Melm, Moritz; Neufeldt, Christopher J.; Cerikan, Berati; Stanifer, Megan L.; Boulant, Steeve; Bartenschlager, Ralf; Chlanda, Petr (December 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 structure and replication characterized by in situ cryo-electron tomography". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5885. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19619-7. PMC 7676268.

- ^ Cai, Yongfei; Zhang, Jun; Xiao, Tianshu; Peng, Hanqin; Sterling, Sarah M.; Walsh, Richard M.; Rawson, Shaun; Rits-Volloch, Sophia; Chen, Bing (25 September 2020). "Distinct conformational states of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein". Science. 369 (6511): 1586–1592. doi:10.1126/science.abd4251. PMC 7464562.

- ^ a b Boson, Bertrand; Legros, Vincent; Zhou, Bingjie; Siret, Eglantine; Mathieu, Cyrille; Cosset, François-Loïc; Lavillette, Dimitri; Denolly, Solène (January 2021). "The SARS-CoV-2 envelope and membrane proteins modulate maturation and retention of the spike protein, allowing assembly of virus-like particles". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 296: 100111. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA120.016175.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Neuman, Benjamin W.; Kiss, Gabriella; Kunding, Andreas H.; Bhella, David; Baksh, M. Fazil; Connelly, Stephen; Droese, Ben; Klaus, Joseph P.; Makino, Shinji; Sawicki, Stanley G.; Siddell, Stuart G.; Stamou, Dimitrios G.; Wilson, Ian A.; Kuhn, Peter; Buchmeier, Michael J. (April 2011). "A structural analysis of M protein in coronavirus assembly and morphology". Journal of Structural Biology. 174 (1): 11–22. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.021.

- ^ Ke, Zunlong; Oton, Joaquin; Qu, Kun; Cortese, Mirko; Zila, Vojtech; McKeane, Lesley; Nakane, Takanori; Zivanov, Jasenko; Neufeldt, Christopher J.; Cerikan, Berati; Lu, John M.; Peukes, Julia; Xiong, Xiaoli; Kräusslich, Hans-Georg; Scheres, Sjors H. W.; Bartenschlager, Ralf; Briggs, John A. G. (17 December 2020). "Structures and distributions of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins on intact virions". Nature. 588 (7838): 498–502. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2665-2.

- ^ a b Lim, Yvonne; Ng, Yan; Tam, James; Liu, Ding (25 July 2016). "Human Coronaviruses: A Review of Virus–Host Interactions". Diseases. 4 (4): 26. doi:10.3390/diseases4030026. PMC 5456285.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Yeager, Curtis L.; Ashmun, Richard A.; Williams, Richard K.; Cardellichio, Christine B.; Shapiro, Linda H.; Look, A. Thomas; Holmes, Kathryn V. (June 1992). "Human aminopeptidase N is a receptor for human coronavirus 229E". Nature. 357 (6377): 420–422. doi:10.1038/357420a0. PMC 7095410.

- ^ Hofmann, H.; Pyrc, K.; van der Hoek, L.; Geier, M.; Berkhout, B.; Pohlmann, S. (31 May 2005). "Human coronavirus NL63 employs the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor for cellular entry". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (22): 7988–7993. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409465102. PMC 1142358.

- ^ Huang, Xingchuan; Dong, Wenjuan; Milewska, Aleksandra; Golda, Anna; Qi, Yonghe; Zhu, Quan K.; Marasco, Wayne A.; Baric, Ralph S.; Sims, Amy C.; Pyrc, Krzysztof; Li, Wenhui; Sui, Jianhua (15 July 2015). "Human Coronavirus HKU1 Spike Protein Uses O -Acetylated Sialic Acid as an Attachment Receptor Determinant and Employs Hemagglutinin-Esterase Protein as a Receptor-Destroying Enzyme". Journal of Virology. 89 (14): 7202–7213. doi:10.1128/JVI.00854-15. PMC 4473545.

- ^ Künkel, Frank; Herrler, Georg (July 1993). "Structural and Functional Analysis of the Surface Protein of Human Coronavirus OC43". Virology. 195 (1): 195–202. doi:10.1006/viro.1993.1360. PMC 7130786.

- ^ Raj, V. Stalin; Mou, Huihui; Smits, Saskia L.; Dekkers, Dick H. W.; Müller, Marcel A.; Dijkman, Ronald; Muth, Doreen; Demmers, Jeroen A. A.; Zaki, Ali; Fouchier, Ron A. M.; Thiel, Volker; Drosten, Christian; Rottier, Peter J. M.; Osterhaus, Albert D. M. E.; Bosch, Berend Jan; Haagmans, Bart L. (March 2013). "Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC". Nature. 495 (7440): 251–254. doi:10.1038/nature12005. PMC 7095326.

- ^ Li, Wenhui; Moore, Michael J.; Vasilieva, Natalya; Sui, Jianhua; Wong, Swee Kee; Berne, Michael A.; Somasundaran, Mohan; Sullivan, John L.; Luzuriaga, Katherine; Greenough, Thomas C.; Choe, Hyeryun; Farzan, Michael (November 2003). "Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus". Nature. 426 (6965): 450–454. doi:10.1038/nature02145. PMC 7095016.

- ^ a b c White, Judith M.; Whittaker, Gary R. (June 2016). "Fusion of Enveloped Viruses in Endosomes". Traffic. 17 (6): 593–614. doi:10.1111/tra.12389. PMC 4866878.

- ^ Premkumar, Lakshmanane; Segovia-Chumbez, Bruno; Jadi, Ramesh; Martinez, David R.; Raut, Rajendra; Markmann, Alena; Cornaby, Caleb; Bartelt, Luther; Weiss, Susan; Park, Yara; Edwards, Caitlin E.; Weimer, Eric; Scherer, Erin M.; Rouphael, Nadine; Edupuganti, Srilatha; Weiskopf, Daniela; Tse, Longping V.; Hou, Yixuan J.; Margolis, David; Sette, Alessandro; Collins, Matthew H.; Schmitz, John; Baric, Ralph S.; de Silva, Aravinda M. (11 June 2020). "The receptor binding domain of the viral spike protein is an immunodominant and highly specific target of antibodies in SARS-CoV-2 patients". Science Immunology. 5 (48): eabc8413. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.abc8413. PMC 7292505.

- ^ a b c d e Harvey, William T.; Carabelli, Alessandro M.; Jackson, Ben; Gupta, Ravindra K.; Thomson, Emma C.; Harrison, Ewan M.; Ludden, Catherine; Reeve, Richard; Rambaut, Andrew; Peacock, Sharon J.; Robertson, David L. (July 2021). "SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 19 (7): 409–424. doi:10.1038/s41579-021-00573-0.

- ^ Fauci, Anthony S. (9 April 2021). "The story behind COVID-19 vaccines". Science. 372 (6538): 109–109. doi:10.1126/science.abi8397.

- ^ Koenig, Paul-Albert; Schmidt, Florian I. (17 June 2021). "Spike D614G — A Candidate Vaccine Antigen Against Covid-19". New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (24): 2349–2351. doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr2106054.

- ^ Hansen, Johanna; Baum, Alina; Pascal, Kristen E.; Russo, Vincenzo; Giordano, Stephanie; Wloga, Elzbieta; Fulton, Benjamin O.; Yan, Ying; Koon, Katrina; Patel, Krunal; Chung, Kyung Min; Hermann, Aynur; Ullman, Erica; Cruz, Jonathan; Rafique, Ashique; Huang, Tammy; Fairhurst, Jeanette; Libertiny, Christen; Malbec, Marine; Lee, Wen-yi; Welsh, Richard; Farr, Glen; Pennington, Seth; Deshpande, Dipali; Cheng, Jemmie; Watty, Anke; Bouffard, Pascal; Babb, Robert; Levenkova, Natasha; Chen, Calvin; Zhang, Bojie; Romero Hernandez, Annabel; Saotome, Kei; Zhou, Yi; Franklin, Matthew; Sivapalasingam, Sumathi; Lye, David Chien; Weston, Stuart; Logue, James; Haupt, Robert; Frieman, Matthew; Chen, Gang; Olson, William; Murphy, Andrew J.; Stahl, Neil; Yancopoulos, George D.; Kyratsous, Christos A. (21 August 2020). "Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail". Science. 369 (6506): 1010–1014. doi:10.1126/science.abd0827. PMC 7299284.

- ^ a b "Therapeutic Management of Nonhospitalized Adults With COVID-19". Covid-19 Treatment Guidelines. National Institutes of Health.

- ^ "etesevimab". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "Lilly announces agreement with U.S. government to supply 300,000 vials of investigational neutralizing antibody bamlanivimab (LY-CoV555) in an effort to fight COVID-19". Eli Lilly and Company (Press release). 28 October 2020.

- ^ "Casirivimab injection, solution, concentrate Imdevimab injection, solution, concentrate REGEN-COV- casirivimab and imdevimab kit". DailyMed. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ "Sotrovimab injection, solution, concentrate". DailyMed. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ^ a b Koyama, Takahiko; Platt, Daniel; Parida, Laxmi (1 July 2020). "Variant analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 98 (7): 495–504. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.253591.

- ^ a b Winger, Anna; Caspari, Thomas (27 May 2021). "The Spike of Concern—The Novel Variants of SARS-CoV-2". Viruses. 13 (6): 1002. doi:10.3390/v13061002.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Saputri, Dianita S.; Li, Songling; van Eerden, Floris J.; Rozewicki, John; Xu, Zichang; Ismanto, Hendra S.; Davila, Ana; Teraguchi, Shunsuke; Katoh, Kazutaka; Standley, Daron M. (17 September 2020). "Flexible, Functional, and Familiar: Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Evolution". Frontiers in Microbiology. 11: 2112. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.02112.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Cagliani, Rachele; Forni, Diego; Clerici, Mario; Sironi, Manuela (June 2020). "Computational Inference of Selection Underlying the Evolution of the Novel Coronavirus, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2". Journal of Virology. 94 (12). doi:10.1128/JVI.00411-20.

- ^ Isabel, Sandra; Graña-Miraglia, Lucía; Gutierrez, Jahir M.; Bundalovic-Torma, Cedoljub; Groves, Helen E.; Isabel, Marc R.; Eshaghi, AliReza; Patel, Samir N.; Gubbay, Jonathan B.; Poutanen, Tomi; Guttman, David S.; Poutanen, Susan M. (December 2020). "Evolutionary and structural analyses of SARS-CoV-2 D614G spike protein mutation now documented worldwide". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 14031. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-70827-z.

- ^ Korber, Bette; Fischer, Will M.; Gnanakaran, Sandrasegaram; Yoon, Hyejin; Theiler, James; Abfalterer, Werner; Hengartner, Nick; Giorgi, Elena E.; Bhattacharya, Tanmoy; Foley, Brian; Hastie, Kathryn M.; Parker, Matthew D.; Partridge, David G.; Evans, Cariad M.; Freeman, Timothy M.; de Silva, Thushan I.; McDanal, Charlene; Perez, Lautaro G.; Tang, Haili; Moon-Walker, Alex; Whelan, Sean P.; LaBranche, Celia C.; Saphire, Erica O.; Montefiori, David C.; Angyal, Adrienne; Brown, Rebecca L.; Carrilero, Laura; Green, Luke R.; Groves, Danielle C.; Johnson, Katie J.; Keeley, Alexander J.; Lindsey, Benjamin B.; Parsons, Paul J.; Raza, Mohammad; Rowland-Jones, Sarah; Smith, Nikki; Tucker, Rachel M.; Wang, Dennis; Wyles, Matthew D. (August 2020). "Tracking Changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: Evidence that D614G Increases Infectivity of the COVID-19 Virus". Cell. 182 (4): 812–827.e19. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.043.

- ^ Zhang, Lizhou; Jackson, Cody B.; Mou, Huihui; Ojha, Amrita; Peng, Haiyong; Quinlan, Brian D.; Rangarajan, Erumbi S.; Pan, Andi; Vanderheiden, Abigail; Suthar, Mehul S.; Li, Wenhui; Izard, Tina; Rader, Christoph; Farzan, Michael; Choe, Hyeryun (December 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein D614G mutation increases virion spike density and infectivity". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 6013. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19808-4.

- ^ Jackson, Cody B.; Zhang, Lizhou; Farzan, Michael; Choe, Hyeryun (January 2021). "Functional importance of the D614G mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 538: 108–115. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.11.026.

- ^ "COVID-19 vaccines are not 'cytotoxic'" (Fact check). Reuters. 18 June 2021.

- ^ Gorski DH (24 May 2021). "The 'deadly' coronavirus spike protein (according to antivaxxers)". Science-Based Medicine.

- ^ McCarthy B (5 May 2021). "Debunking the anti-vaccine hoax about 'vaccine shedding'". PolitiFact. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Fiore K (29 April 2021). "The Latest Anti-Vax Myth: 'Vaccine Shedding'". MedPage Today. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ Vance, Tyler D.R.; Lee, Jeffrey E. (July 2020). "Virus and eukaryote fusogen superfamilies". Current Biology. 30 (13): R750–R754. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.05.029.

- ^ Li, F. (1 March 2012). "Evidence for a Common Evolutionary Origin of Coronavirus Spike Protein Receptor-Binding Subunits". Journal of Virology. 86 (5): 2856–2858. doi:10.1128/jvi.06882-11.

- ^ Shang, Jian; Zheng, Yuan; Yang, Yang; Liu, Chang; Geng, Qibin; Luo, Chuming; Zhang, Wei; Li, Fang (23 April 2018). "Cryo-EM structure of infectious bronchitis coronavirus spike protein reveals structural and functional evolution of coronavirus spike proteins". PLOS Pathogens. 14 (4): e1007009. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1007009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

External links

- Scudellari, Megan (28 July 2021). "How the coronavirus infects cells — and why Delta is so dangerous". Nature. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- Iwasa, Janet; Meyer, Miriah; Lex, Alexander; Rogers, Jen; Liu, Ann (Hui); Riggi, Margot. "Building a visual consensus model of the SARS-CoV-2 life cycle". Animation Lab. University of Utah. Retrieved 15 August 2021.