Neurolathyrism: Difference between revisions

Quisqualis (talk | contribs) →Related conditions: Copyedit (minor) |

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Alter: url, title. URLs might have been anonymized. Add: s2cid, bibcode, doi, authors 1-1. Removed proxy/dead URL that duplicated identifier. Removed parameters. Some additions/deletions were parameter name changes. Upgrade ISBN10 to 13. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Abductive | #UCB_webform 1612/3850 |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

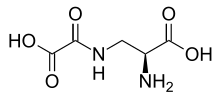

'''Neurolathyrism''', is a [[neurological disease]] of humans, caused by eating certain [[legumes]] of the [[genus]] ''[[Lathyrus]]''. This disease is mainly associated with the consumption of ''[[Lathyrus sativus]]'' (also known as ''grass pea'', ''chickling pea'', ''kesari dal'', or ''almorta'') and to a lesser degree with ''[[Lathyrus cicera]]'', ''[[Lathyrus ochrus]]'' and ''[[Lathyrus clymenum]]''<ref>[http://www.itg.be/itg/DistanceLearning/LectureNotesVandenEndenE/47_Medical_problems_caused_by_plantsp11.htm "Medical problems caused by plants: Lathyrism"] at ''Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine'' online database</ref> containing the [[toxin]] [[Oxalyldiaminopropionic acid|ODAP]]. |

'''Neurolathyrism''', is a [[neurological disease]] of humans, caused by eating certain [[legumes]] of the [[genus]] ''[[Lathyrus]]''. This disease is mainly associated with the consumption of ''[[Lathyrus sativus]]'' (also known as ''grass pea'', ''chickling pea'', ''kesari dal'', or ''almorta'') and to a lesser degree with ''[[Lathyrus cicera]]'', ''[[Lathyrus ochrus]]'' and ''[[Lathyrus clymenum]]''<ref>[http://www.itg.be/itg/DistanceLearning/LectureNotesVandenEndenE/47_Medical_problems_caused_by_plantsp11.htm "Medical problems caused by plants: Lathyrism"] at ''Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine'' online database</ref> containing the [[toxin]] [[Oxalyldiaminopropionic acid|ODAP]]. |

||

This is not to be confused with [[osteolathyrism]], a different type of lathyrism that affects the connective tissues.<ref name="AEF1982">{{cite book |last1=Ahmad |first1=Kamal |title=Adverse Effects of Foods |date=1982 |publisher=Springer US |location=Springer, Massachusettes |isbn=978-1-4613-3359-3 |pages=71–2 |url=https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-1-4613-3359-3_8 |

This is not to be confused with [[osteolathyrism]], a different type of lathyrism that affects the connective tissues.<ref name="AEF1982">{{cite book |last1=Ahmad |first1=Kamal |title=Adverse Effects of Foods |date=1982 |publisher=Springer US |location=Springer, Massachusettes |isbn=978-1-4613-3359-3 |pages=71–2 |doi=10.1007/978-1-4613-3359-3_8 |url=https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-1-4613-3359-3_8 |access-date=30 June 2020}}</ref> Osteolathyrism results from the ingestion of ''[[Sweet pea|Lathyrus odoratus]]'' seeds (''sweet peas'') and is often referred to as odoratism. It is caused by a different toxin ([[beta-aminopropionitrile]]) which affects the linking of [[collagen]], a [[protein]] of [[connective tissue]]s. |

||

Another type of lathyrism is [[angiolathyrism]] which is similar to osteolathyrism in its effects on connective tissue. However, the blood vessels are affected as opposed to bone. |

Another type of lathyrism is [[angiolathyrism]] which is similar to osteolathyrism in its effects on connective tissue. However, the blood vessels are affected as opposed to bone. |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

===Association with famine=== |

===Association with famine=== |

||

Ingestion of legumes containing the toxin occurs despite an awareness of the means to detoxify Lathyrus.<ref>{{Cite journal| |

Ingestion of legumes containing the toxin occurs despite an awareness of the means to detoxify Lathyrus.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Jahan|first1=K.|last2=Ahmad|first2=K.|date=June 1984|title=Detoxification of Lathyrus Sativus|journal=Food and Nutrition Bulletin|language=en|volume=6|issue=2|pages=1–2|doi=10.1177/156482658400600213|issn=0379-5721|doi-access=free}}</ref> Drought conditions can lead to shortages of both fuel and water, preventing the necessary detoxification steps from being taken, particularly in impoverished countries.<ref name=patient/> Lathyrism usually occurs where the combination of [[poverty]] and [[food insecurity]] leaves few other food options. |

||

==Prevention== |

==Prevention== |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

==Epidemiology== |

==Epidemiology== |

||

This disease is prevalent in some areas of [[Bangladesh]], [[Ethiopia]], [[India]] and [[Nepal]],<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Spencer P. S. |author2=Ludolph A. C. |author3=Kisby G. E. |title = Neurologic diseases associated with use of plant components with toxic potential | journal=Environmental Research |date=July 1993 | issue=1 | volume=62 | pages= 106–113 |doi = 10.1006/enrs.1993.1095 | pmid = 8325256}}</ref> and affects more men than women. Men between 25 and 40 are particularly vulnerable.<ref name=patient>[http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/Lathyrism.htm Lathyrism]</ref> |

This disease is prevalent in some areas of [[Bangladesh]], [[Ethiopia]], [[India]] and [[Nepal]],<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Spencer P. S. |author2=Ludolph A. C. |author3=Kisby G. E. |title = Neurologic diseases associated with use of plant components with toxic potential | journal=Environmental Research |date=July 1993 | issue=1 | volume=62 | pages= 106–113 |doi = 10.1006/enrs.1993.1095 | pmid = 8325256|bibcode=1993ER.....62..106S }}</ref> and affects more men than women. Men between 25 and 40 are particularly vulnerable.<ref name=patient>[http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/Lathyrism.htm Lathyrism]</ref> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

The first mentioned intoxication goes back to ancient India and also [[Hippocrates]] mentions a neurological disorder 46 B.C. in Greece caused by Lathyrus seed.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Mark V. Barrow |author2=Charles F. Simpson |author3=Edward J. Miller | title = Lathyrism: A Review | year = 1974 | journal = The Quarterly Review of Biology | volume = 49 | issue = 2 | pages = 101–128 | doi = 10.1086/408017 | pmid = 4601279 | jstor=2820941}}</ref> |

The first mentioned intoxication goes back to ancient India and also [[Hippocrates]] mentions a neurological disorder 46 B.C. in Greece caused by Lathyrus seed.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Mark V. Barrow |author2=Charles F. Simpson |author3=Edward J. Miller | title = Lathyrism: A Review | year = 1974 | journal = The Quarterly Review of Biology | volume = 49 | issue = 2 | pages = 101–128 | doi = 10.1086/408017 | pmid = 4601279 | jstor=2820941|s2cid=33451792 }}</ref> |

||

During the [[Peninsular War|Spanish War of Independence]] against Napoleon, grasspea served as a famine food. This was the subject of one of [[Francisco de Goya]]'s famous aquatint prints titled ''Gracias a la Almorta'' ("Thanks to the Grasspea"), depicting poor people surviving on a porridge made from grasspea flour, one of them lying on the floor, already crippled by it. |

During the [[Peninsular War|Spanish War of Independence]] against Napoleon, grasspea served as a famine food. This was the subject of one of [[Francisco de Goya]]'s famous aquatint prints titled ''Gracias a la Almorta'' ("Thanks to the Grasspea"), depicting poor people surviving on a porridge made from grasspea flour, one of them lying on the floor, already crippled by it. |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

==Modern occurrence== |

==Modern occurrence== |

||

During the [[Spain under Franco#Isolation (1945–1953)|post Civil war period]] in Spain, there were several outbreaks of lathyrism, caused by the shortage of food, which led people to consume excessive amounts of almorta flour.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.historiacocina.com/gourmets/venenos/almortas.htm |title=AZCOYTIA, Carlos (2006): "''Historia de la Almorta or el veneno que llegó con el hambre tras la Guerra Civil Española''". ' |

During the [[Spain under Franco#Isolation (1945–1953)|post Civil war period]] in Spain, there were several outbreaks of lathyrism, caused by the shortage of food, which led people to consume excessive amounts of almorta flour.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.historiacocina.com/gourmets/venenos/almortas.htm |title=AZCOYTIA, Carlos (2006): "''Historia de la Almorta or el veneno que llegó con el hambre tras la Guerra Civil Española''". ''HistoriaCocina'' |publisher=Historiacocina.com |access-date=2013-09-23}}</ref> |

||

In Spain, a seed mixture known as comuña<ref>The etymological origin of this name is from "común" (''common'') in its meaning of mixture, referring to the mix of seeds obtained when cleaning the grain and which contaminate the main grain, generally wheat.</ref> consisting of ''Lathyrus sativus'', ''L. cicera'', ''Vicia sativa'' and ''V. ervilia'' provides a potent mixture of toxic amino acids to poison monogastric (single stomached) animals. Particularly the toxin [[cyanoalanine|β-cyanoalanine]] from seeds of ''V. sativa'' enhances the toxicity of such a mixture through its inhibition of sulfur amino acid metabolism (conversion of methionine to cysteine leading to excretion of cystathionine in urine) and hence depletion of protective reduced thiols. Its use for sheep does not pose any lathyrism problems if doses do not exceed 50 percent of the ration.<ref>{{cite book| title=Neglected crops 1492 from a different perspective| url=http://www.fao.org/docrep/t0646e/T0646E0q.htm | author=J.E. Hernández Bermejo |author2=J. León| publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations | location=Rome | year=1994 | isbn = 92-5-103217-3}}</ref> |

In Spain, a seed mixture known as comuña<ref>The etymological origin of this name is from "común" (''common'') in its meaning of mixture, referring to the mix of seeds obtained when cleaning the grain and which contaminate the main grain, generally wheat.</ref> consisting of ''Lathyrus sativus'', ''L. cicera'', ''Vicia sativa'' and ''V. ervilia'' provides a potent mixture of toxic amino acids to poison monogastric (single stomached) animals. Particularly the toxin [[cyanoalanine|β-cyanoalanine]] from seeds of ''V. sativa'' enhances the toxicity of such a mixture through its inhibition of sulfur amino acid metabolism (conversion of methionine to cysteine leading to excretion of cystathionine in urine) and hence depletion of protective reduced thiols. Its use for sheep does not pose any lathyrism problems if doses do not exceed 50 percent of the ration.<ref>{{cite book| title=Neglected crops 1492 from a different perspective| url=http://www.fao.org/docrep/t0646e/T0646E0q.htm | author=J.E. Hernández Bermejo |author2=J. León| publisher=Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations | location=Rome | year=1994 | isbn = 92-5-103217-3}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 02:03, 26 August 2022

| Neurolathyrism | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Weakness, fatigue, paralysis of the legs, atrophy of leg muscles |

| Usual onset | Gradual |

| Duration | Permanent |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and diet |

| Frequency | Rare |

Neurolathyrism, is a neurological disease of humans, caused by eating certain legumes of the genus Lathyrus. This disease is mainly associated with the consumption of Lathyrus sativus (also known as grass pea, chickling pea, kesari dal, or almorta) and to a lesser degree with Lathyrus cicera, Lathyrus ochrus and Lathyrus clymenum[1] containing the toxin ODAP.

This is not to be confused with osteolathyrism, a different type of lathyrism that affects the connective tissues.[2] Osteolathyrism results from the ingestion of Lathyrus odoratus seeds (sweet peas) and is often referred to as odoratism. It is caused by a different toxin (beta-aminopropionitrile) which affects the linking of collagen, a protein of connective tissues.

Another type of lathyrism is angiolathyrism which is similar to osteolathyrism in its effects on connective tissue. However, the blood vessels are affected as opposed to bone.

Signs and symptoms

The consumption of large quantities of Lathyrus seeds containing high concentrations of the neurotoxic glutamate analogue β-oxalyl-L-α,β-diaminopropionic acid (ODAP, also known as β-N-oxalyl-amino-L-alanine, or BOAA) causes paralysis, characterized by lack of strength in or inability to move the lower limbs, and may involve pyramidal tracts, producing signs of upper motor neuron damage. The toxin may also cause aortic aneurysm.[3][4] A unique symptom of lathyrism is the atrophy of gluteal (buttocks) muscles. ODAP is a poison of the mitochondria,[4] leading to excess cell death, especially in motor neurons. [citation needed] Children can additionally develop bone deformity and reduced brain development.[5]

Causes

The toxicological cause of the disease has been attributed to the neurotoxin ODAP which acts as a structural analogue of the neurotransmitter glutamate. Lathyrism can also be caused by deliberate food adulteration.

Association with famine

Ingestion of legumes containing the toxin occurs despite an awareness of the means to detoxify Lathyrus.[6] Drought conditions can lead to shortages of both fuel and water, preventing the necessary detoxification steps from being taken, particularly in impoverished countries.[5] Lathyrism usually occurs where the combination of poverty and food insecurity leaves few other food options.

Prevention

Eating the chickling pea with legumes having high concentrations of sulphur-based amino acids reduces the risk of lathyrism if such grain is available. Food preparation is also an important factor. Toxic amino acids are readily soluble in water and can be leached. Bacterial (lactic acid) and fungal (tempeh) fermentation is useful to reduce ODAP content. Moist heat (boiling, steaming) denatures protease inhibitors which otherwise add to the toxic effect of raw chickling pea through depletion of protective sulfur amino acids. During drought and famine, water for steeping and fuel for boiling are often also in short supply. Poor people sometimes know how to reduce the chance of developing lathyrism but face a choice between starvation and risking lathyrism.[5]

Epidemiology

This disease is prevalent in some areas of Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India and Nepal,[7] and affects more men than women. Men between 25 and 40 are particularly vulnerable.[5]

History

The first mentioned intoxication goes back to ancient India and also Hippocrates mentions a neurological disorder 46 B.C. in Greece caused by Lathyrus seed.[8]

During the Spanish War of Independence against Napoleon, grasspea served as a famine food. This was the subject of one of Francisco de Goya's famous aquatint prints titled Gracias a la Almorta ("Thanks to the Grasspea"), depicting poor people surviving on a porridge made from grasspea flour, one of them lying on the floor, already crippled by it.

During WWII, on the order of Colonel I. Murgescu, commandant of the Vapniarka concentration camp in Transnistria, the detainees - most of them Jews - were fed nearly exclusively with fodder pea. Consequently, they became ill from lathyrism.[9]

Modern occurrence

During the post Civil war period in Spain, there were several outbreaks of lathyrism, caused by the shortage of food, which led people to consume excessive amounts of almorta flour.[10]

In Spain, a seed mixture known as comuña[11] consisting of Lathyrus sativus, L. cicera, Vicia sativa and V. ervilia provides a potent mixture of toxic amino acids to poison monogastric (single stomached) animals. Particularly the toxin β-cyanoalanine from seeds of V. sativa enhances the toxicity of such a mixture through its inhibition of sulfur amino acid metabolism (conversion of methionine to cysteine leading to excretion of cystathionine in urine) and hence depletion of protective reduced thiols. Its use for sheep does not pose any lathyrism problems if doses do not exceed 50 percent of the ration.[12]

Ronald Hamilton suggested in his paper The Silent Fire: ODAP and the death of Christopher McCandless that itinerant traveler Christopher McCandless may have died from starvation after being unable to hunt or gather food due to lathyrism-induced paralysis of his legs caused by eating the seeds of Hedysarum alpinum.[13] In 2014, a preliminary lab analysis indicated that the seeds did contain ODAP.[14] However, a more detailed mass spectrometric analysis conclusively ruled out ODAP, with a molecular weight of 176.13 and lathyrism, and instead found that the most significant contributor to his death was the toxic action of L-canavanine, with a molecular weight of 176.00, which was found in significant quantity in the Hedysarum alpinum seeds he was eating.[15]

Related conditions

A related disease has been identified and named osteolathyrism, because it affects the bones and connecting tissues, instead of the nervous system. It is a skeletal disorder, caused by the toxin beta-aminopropionitrile (BAPN), and characterized by hernias, aortic dissection, exostoses, and kyphoscoliosis and other skeletal deformities, apparently as the result of defective aging of collagen tissue. The cause of this disease is attributed to beta-aminopropionitrile, which inhibits the copper-containing enzyme lysyl oxidase, responsible for cross-linking procollagen and proelastin. BAPN is also a metabolic product of a compound present in sprouts of grasspea, pea and lentils.[16] Disorders that are clinically similar are konzo and lytico-bodig disease.

References

- ^ "Medical problems caused by plants: Lathyrism" at Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine online database

- ^ Ahmad, Kamal (1982). Adverse Effects of Foods. Springer, Massachusettes: Springer US. pp. 71–2. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-3359-3_8. ISBN 978-1-4613-3359-3. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Neurology in Africa. 2012. pp. 248–249.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b "Lathyrism". Egton Medical Information Systems Limited.

- ^ a b c d Lathyrism

- ^ Jahan, K.; Ahmad, K. (June 1984). "Detoxification of Lathyrus Sativus". Food and Nutrition Bulletin. 6 (2): 1–2. doi:10.1177/156482658400600213. ISSN 0379-5721.

- ^ Spencer P. S.; Ludolph A. C.; Kisby G. E. (July 1993). "Neurologic diseases associated with use of plant components with toxic potential". Environmental Research. 62 (1): 106–113. Bibcode:1993ER.....62..106S. doi:10.1006/enrs.1993.1095. PMID 8325256.

- ^ Mark V. Barrow; Charles F. Simpson; Edward J. Miller (1974). "Lathyrism: A Review". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 49 (2): 101–128. doi:10.1086/408017. JSTOR 2820941. PMID 4601279. S2CID 33451792.

- ^ isurvived.org: The Holocaust in Romania Under the Antonescu Government, by Marcu Rozen.

- ^ "AZCOYTIA, Carlos (2006): "Historia de la Almorta or el veneno que llegó con el hambre tras la Guerra Civil Española". HistoriaCocina". Historiacocina.com. Retrieved 2013-09-23.

- ^ The etymological origin of this name is from "común" (common) in its meaning of mixture, referring to the mix of seeds obtained when cleaning the grain and which contaminate the main grain, generally wheat.

- ^ J.E. Hernández Bermejo; J. León (1994). Neglected crops 1492 from a different perspective. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 92-5-103217-3.

- ^ Ronald Hamilton (September 12, 2013). "ODAP and the death of Christopher McCandless".

- ^ newyorker.com

- ^ newyorker.com

- ^ COHN, D.F. (1995) "Are other systems apart from the nervous system involved in human lathyrism?" in Lathyrus sativus and Human Lathyrism: Progress and Prospects. Ed. Yusuf H, Lambein F. University of Dhaka. Dhaka pp. 101-2.

External links

- Lathyrism at the Duke University Health System's Orthopedics program

- Detection of Toxic Lathyrus sativus flour in Gram Flour