Zhoubi Suanjing: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

LlywelynII (talk | contribs) cleanup; correction; formatting; add'l sources |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Italic title}} |

{{Italic title}} |

||

{{Expand Chinese|周髀算經|date=May 2018}} |

{{Expand Chinese|周髀算經|date=May 2018}} |

||

{{Infobox Chinese |

|||

{{Infobox Chinese|t=周髀算經|s=周髀算经|w=Chou Pi Suan Ching|l=[[Zhou dynasty|Zhou]] [[gnomon]] arithmetic [[Chinese classic|classic]]|p=Zhōu bì suàn jīng}} |

|||

|pic=Chinese pythagoras.jpg |

|||

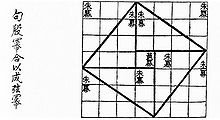

[[File:Chinese pythagoras.jpg|thumb|250px|Diagram added by Zhao Shuang to the ''Zhoubi Suanjing'' that can be used to prove the Pythagorean Theorem]] |

|||

|piccap=Diagram added to the Zhoubi by Zhao Shuang |

|||

The '''''Zhoubi Suanjing''''' ({{zh|t=周髀算經}}) is one of the oldest [[Chinese mathematics|Chinese mathematical]] texts. "Zhou" refers to the ancient [[Zhou dynasty]] (1046–256 BCE); "Bì" literally means "[[thigh]]", but in the book refers to the gnomon of a [[Sundial|sundial]]. The book is dedicated to astronomical observation and calculation. ''Suan Jing'' or "classic of arithmetics" were appended in later time to honor the achievement of the book in mathematics. |

|||

|title= |

|||

|name1=Zhoubi Suanjing |

|||

|t=《{{linktext|周|髀|算|經}}》 |

|||

|s=《{{linktext|周|髀|算|经}}》 |

|||

|p=Zhōubì suànjīng |

|||

|w=Chou-pi Suan-ching |

|||

|altname=Zhoubi |

|||

|c2=《{{linktext|周|髀}}》 |

|||

|p2=Zhōubì |

|||

|w2=Chou-pi |

|||

|l2=The [[Zhou dynasty|Zhou]] [[Gnomon]]<br>On [[Gnomon]]s and Circular Paths |

|||

|altname3=Zhoubi |

|||

|t3=《{{linktext|算|經}}》 |

|||

|s3=《{{linktext|算|经}}》 |

|||

|p3=Suànjīng |

|||

|w3=Suan-ching |

|||

|l3=The Classic of Computation<br>The Arithmetic Classic |

|||

}} |

|||

The '''''Zhoubi Suanjing''''',<!--Chinese in infobox; see [[WP:MOS-ZH]]--> also known by [[#Names|many other names]], is an [[ancient China|ancient]] [[Classical Chinese|Chinese]] [[Chinese astronomy|astronomical]] and [[Chinese mathematics|mathematical]] work. The ''Zhoubi'' is most famous for its presentation of [[Chinese cosmology]] and a form of the [[Pythagorean theorem]]. It claims to present 246 problems worked out by the [[Western Zhou|early Zhou]] [[culture hero]] [[Duke of Zhou|Ji Dan]] and members of his court, placing its contents in the 11th century{{nbsp}}{{sc|bc}}. However, the present form of the book does not seem to be earlier than the 2nd century [[Eastern Han]], with some additions and commentaries continuing to be added for several more centuries. |

|||

This book dates from the period of the Zhou dynasty, yet its compilation and addition of materials continued into the [[Han dynasty]] (202 BCE–220 CE). It is an anonymous collection of 246 problems encountered by the [[Duke of Zhou]] and his [[astronomer]] and mathematician, Shang Gao. Each question has stated their numerical answer and corresponding arithmetic [[algorithm]]. |

|||

{{anchor|Name|Etymology|Translation|Meaning}} |

|||

The book also makes use of the [[Pythagorean Theorem]] on various occasions{{sfnp|Cullen|1996|p=82}} and might also contain a geometric proof of the theorem for the case of the 3-4-5 triangle {{sfnp|Chemla|2005|p={{page needed|date=October 2020}}}} (but the procedure works for a general right triangle as well). Zhao Shuang (3rd century CE) added a commentary to the text, and also included the diagram depicted on this page, which seems to correspond to the geometric figure alluded to in the original text .{{sfnp|Cullen|1996|p=208}} |

|||

==Names== |

|||

''Zhoubi Suanjing'' is the [[atonal]] [[pinyin]] [[romanization of Chinese|romanization]] of the [[Standard Mandarin|modern standard Mandarin]] pronunciation of the work's [[Classical Chinese]] name, {{lang|zh|《{{linktext|周|髀|算|經}}》}}. The same name has been variously romanized as the '''''Chou Pei Suan Ching'''',<ref name=needy>{{harvp|Needham & al.|1959|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=jfQ9E0u4pLAC&pg=RA1-PA815 815]}}.</ref> the '''''Tcheou-pi Souane''''',{{sfnp|''EB'', 1st ed.|1771|p=188}} &c. Its original title was simply the '''''Zhoubi'''''. The character {{lang|zh|{{linktext|髀}}}} is a literary term for the [[femur]] or [[thighbone]] but in context only refers to one or more [[gnomon]]s, large sticks whose [[shadow]]s were used for [[Chinese calendar|Chinese calendrical]] and [[Chinese astronomy|astronomical calculations]].<ref name=needy2/> Because of the ambiguous nature of the character {{lang|zh|{{linktext|周}}}}, it has been alternately understood and translated as "On the Gnomon and the Circular Paths of [[Tian|Heaven]]",<ref name=needy2>{{harvp|Needham & al.|1959|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=jfQ9E0u4pLAC&pg=RA1-PA19 19]}}.</ref> the ''Zhou Shadow Gauge Manual'',<ref name=zoo>{{harvp|Zou|2011|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=fD6p-LR_G7UC&pg=PA104 104]}}.</ref> ''The Gnomon of the Zhou [[Sundial]]'', {{sfnp|Pang-White|2018|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=EaRTDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT464 464]}} and ''Gnomon of the [[Zhou Dynasty]]''.<ref name=cully>{{harvp|Cullen|2018|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=DWV9DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT758 758]}}.</ref> The honorific '''''Suanjing'''''{{mdash}}''Arithmetical Classic'',<ref name=needy/> ''Sacred Book of Arithmetic'',{{sfnp|Davis & al.|1995|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=I1fj_B60fyoC&pg=PA28 28]}} ''Mathematical Canon'',<ref name=cully/> ''Classic of Computations'',{{sfnp|Elman|2015|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=lbMyBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA240 240]}} &c.{{mdash}}was added later. |

|||

==Dating== |

|||

There is some disagreement among historians whether the text actually constitutes a proof of the theorem.{{sfnp|Chemla|2005|p={{page needed|date=October 2020}}}} This is in part because the famous diagram was not included in the original text and the description in the original text is subject to some interpretation (see the different translations of {{harvnb|Chemla|2005}} and {{harvnb|Cullen|1996|p=82}}). |

|||

Examples of the [[gnomon]] described in the work have been found from as early as 2300{{nbsp}}{{sc|bc}} and Ji Dan, better known as the [[Duke of Zhou]], was an 11th century{{nbsp}}{{sc|bc}} [[regent]] and [[Chinese nobility|noble]] during the first generation of the [[Zhou dynasty]]. The ''Zhoubi'' was traditionally dated to Ji Dan's own life<ref name=needy3>{{harvp|Needham & al.|1959|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=jfQ9E0u4pLAC&pg=RA1-PA20 20]}}.</ref> and considered to be the oldest Chinese mathematical treatise.<ref name=needy2/> However, although some passages seem to come from the [[Warring States Period]] or earlier,<ref name=needy3/> the current text of the work mentions [[Lü Bowei]] and is believed to have received its current form no earlier than the [[Eastern Han dynasty|Eastern Han]], during the 1st or 2nd century. It does not appear at all in the [[Qianhanshu|Book of Han]]'s account of calendrical, astronomical, and mathematical works, although [[Joseph Needham]] allows that this may have been from its current contents having previously been provided in several different works listed in the Han history which are otherwise unknown.<ref name=needy2/> |

|||

==Contents== |

|||

Other commentators such as [[Liu Hui]] (263 CE), [[Zu Gengzhi]] (early sixth century), [[Li Chunfeng]] (602–670 CE) and [[Yang Hui]] (1270 CE) have expanded on this text. |

|||

[[File:TERRACOTTA ARMY @ Gdynia 2006 - 01 ubt.jpeg|thumb|right|250px|A [[umbrella]]-covered [[Chinese chariot|chariot]] from the [[terracotta army]] of the [[Tomb of Qin Shi Huang|tomb]] of the [[Shi Huangdi|First Emperor]] (2006).]] |

|||

The ''Zhoubi'' is an anonymous collection of 246 problems{{dubious}} encountered by the [[Duke of Zhou]] and figures in his court, including the [[Chinese astrology|astrologer]] Shang Gao ([[pinyin]]) or Kao ([[Wade-Giles]]). Each problem includes an answer and a corresponding arithmetic [[algorithm]]. |

|||

It is an important source on early [[Chinese cosmology]], glossing the ancient idea of a round heaven over a square earth ({{lang|zh|{{linktext|天|圆|地|方}}, ''tiānyuán dìfāng'') as similar to the round parasol suspended over some ancient [[Chinese chariot]]s{{sfnp|Tseng|2011|pp=45–49}} or a [[Chinese chess]]board.{{sfnp|Ding|2020|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=kSn_DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA172 172]}} All things measurable were considered variants of the [[square]], while the expansion of a polygon to [[infinity|infinite]] sides approaches the immeasurable [[circle]].<ref name=zoo/> This concept of a "canopy heaven" ({{lang|zh|{{linktext|蓋|天}}}}, ''gàitiān'') had earlier produced the [[Chinese jade|jade]] [[Bi (jade)|''bì'']] ({{lang|zh|{{linktext|璧}}}}) and [[Cong_(vessel)|''cóng'']] ({{lang|zh|{{linktext|琮}}}}) objects and [[Chinese mythology|myths]] about [[Gonggong]], [[Mount Buzhou]], [[Nüwa]], and [[Nüwa Mends the Heavens|repairing the sky]]. Although this eventually developed into an idea of a "spherical heaven" ({{lang|zh|{{linktext|渾|天}}}}, ''hùntiān''),{{sfnp|Tseng|2011|p=50}} the ''Zhoubi'' offers numerous explorations of the [[geometry|geometric]] relationships of simple circles [[Circumscribed quadrilateral|circumscribed by squares]] and squares [[circumscribed circle|circumscribed by circles]].{{sfnp|Tseng|2011|p=51}} A large part of this involves analysis of [[solar declination]] in the [[Northern Hemisphere]] at various points throughout the year.<ref name=needy2/> |

|||

==Background behind Pythagorean derivation== |

|||

At this early point in Chinese history the model of the ancient Chinese equivalent of Heaven, 天 [[Tian]], was symbolized as a circle and the earth was symbolized as a square. In order to make this concept easily understood the adopted symbol of the heavens was the ancient Chinese chariot. The charioteer would stand in the square body of the vehicle and a "canopy", the equivalent of an umbrella, stood next to them. The world was thus likened to the chariot in that the earth, the square, was where the charioteer stood, and heaven, the circle, was suspended above them. The concept has thus been termed "Canopy Heaven", 蓋天 (Gaitian).{{sfnp|Tseng|2011|pp=45–49}} |

|||

At one point during its discussion of the shadows cast by gnomons, the work presents a form of the [[Pythagorean theorem]] known as the '''gougu theorem''' ({{lang|zh|{{linktext|勾股|定理}}}}, ''gōugǔ dìnglǐ''){{sfnp|Cullen|1996|p=82}} from the Chinese names{{mdash}}lit. "hook" and "thigh"{{mdash}}of the two sides of the [[carpenter square|carpenter]] or [[try square]].{{sfnp|Gamwell|2016|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=DfI8CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA39 39]}} In the 3rd century, [[Zhao Shuang]]'s commentary on the ''Zhoubi'' included a diagram effectively proving the theorem{{sfnp|Cullen|1996|p=208}} for the case of a [[3-4-5 triangle]],{{sfnp|Chemla|2005|p={{page needed|date=October 2020}}}} whence it can be generalized to all [[right triangle]]s. The original text being ambiguous on its own, there is disagreement as to whether this proof was established by Zhao or merely represented an illustration of a previously understood concept earlier than [[Pythagoras]].{{sfnp|Chemla|2005}}{{sfnp|Cullen|1996|p=82}} Shang Gao concludes the gougu problem saying "He who understands the [[geometry|earth]] is a [[wisdom|wise man]], and he who understands the [[Chinese astronomy|heavens]] is a [[sage (philosophy)|sage]]. Knowledge is derived from the [[shadow]] [straight line], and the shadow is derived from the [[gnomon]] [right angle]. The combination of the gnomon with [[Chinese numbers|numbers]] is what guides and rules the [[phenomenon|myriad things]]."{{sfnp|Gamwell|2016|p=[https://books.google.fr/books?id=DfI8CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA41 41]}} |

|||

Eventually the populace began to turn away from the "Canopy Heaven" concept in favor of the concept termed "Spherical Heaven", 渾天 (Huntian). This was partly due to the fact that the people were having trouble accepting heaven's encompassment of the earth in the fashion of a chariot canopy because the corners of the chariot were themselves relatively uncovered.{{sfnp|Tseng|2011|p=50}} In contrast, "Spherical Heaven", Huntian, has Heaven, [[Tian]], completely surrounding and containing the Earth and was therefore more appealing. Despite this switch in popularity, supporters of the Gaitian "Canopy Heaven" model continued to delve into the planar relationship between the circle and square as they were significant in symbology. In their investigation of the geometric relationship between circles circumscribed by squares and squares circumscribed by circles the author of the Zhoubi Suanjing deduced one instance of what today is known as the [[Pythagorean Theorem]].{{sfnp|Tseng|2011|p=51}} |

|||

==Commentaries== |

|||

The ''Zhoubi'' has had a prominent place in [[Chinese mathematics]] and was the subject of specific commentaries by Zhao Shuang in the 3rd century, [[Liu Hui]] in 263, by [[Zu Gengzhi]] in the early 6th century, [[Li Chunfeng]] in the 7th century, and [[Yang Hui]] in 1270. |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

| Line 23: | Line 48: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

===Citations=== |

===Citations=== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist|30em}} |

||

===Works Cited=== |

===Works Cited=== |

||

* {{citation |last= |first= |editor-last=Smellie |editor-first=William |editor-link=William Smellie |display-editors=0 |contribution=[[:s:Encyclopædia Britannica, First Edition/Chinese|Chinese]] |title=[[:s:EB1|Encyclopaedia Britannica]] |edition=1st |volume=II |date=1771 |location=Edinburgh |publisher=[[Colin Macfarquhar]] |ref={{harvp|''EB'', 1st ed.|1771}} |pp=184-192 }}. |

|||

*{{cite book |author-link=Karine Chemla |last=Chemla |first= Karine |title=Geometrical Figures and Generality in Ancient China and Beyond |publisher= Science in Context |year=2005 |isbn=0-521-55089-0}} |

|||

*{{ |

* {{citation |author-link=Karine Chemla |last=Chemla |first= Karine |title=Geometrical Figures and Generality in Ancient China and Beyond |publisher=Science in Context |location= |year=2005 |isbn=0-521-55089-0 }}. |

||

*{{ |

* {{citation |author-link=Christopher Cullen |last=Cullen |first=Christopher |title=Astronomy and Mathematics in Ancient China |publisher= Cambridge University Press |location=[[Cambridge, England|Cambridge]] |year=1996 |isbn=0-521-55089-0}}. |

||

* {{citation |url=https://books.google.fr/books?id=DWV9DwAAQBAJ |title=The Cambridge History of Science, ''Vol. I:'' Ancient Science |editor-last=Jones |editor-first=Alexander |editor-last2=Taub |editors-first2=Liba |display-editors=0 |last=Cullen |first=Christopher |contribution=Chinese Astronomy in the Early Imperial Age |location=[[Cambridge, England|Cambridge]] |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=2018 }}. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{citation |editor-last=Davis |editor-first=Philip J. |editor-last2=Hersch |editor-first2=Reuben |editor-last3=Marchisotto |editor-first3=Elena Anne |url=https://books.google.fr/books?id=I1fj_B60fyoC |series=''Modern Birkhäuser Classics'' |title=The Mathematical Experience |publisher=Birkhäuser |date=1995 |location=Boston |contribution-url=https://books.google.fr/books?id=I1fj_B60fyoC&pg=PA26 |pp=26-29 |contribution=Brief Chronological Table to 1910 |display-editors=1 |ref={{harvp|Davis & al.|1995}} }}. |

|||

* {{citation |last=Ding |first=Daniel D.X. |url=https://books.google.fr/books?id=kSn_DwAAQBAJ |title=The Historical Roots of Technical Communication in the Chinese Tradition |date=2020 |publisher=Cambridge Scholars |location=Newcastle-upon-Tyne }}. |

|||

* {{citation |last=Elman |first=Benjamin |contribution-url= |pp=225-244 |contribution=Early Modern or Late Imperial? The Crisis of Classical Philology in Eighteenth-Century China |editor=Sheldon Pollock |editor2=Benjamin A. Elman |editor3=Chang Ku-ming |display-editors=0 |date=2015 |publisher=Harvard University Press |location=[[Cambridge, Massachusetts|Cambridge]] }}. |

|||

* {{citation |last=Gamwell |first=Lynn |url=https://books.google.fr/books?id=DfI8CgAAQBAJ |title=Mathematics + Art: A Cultural History |date=2016 |location=Princeton |publisher=Princeton University Press }}. |

|||

* {{citation |last=Needham |first=Joseph |location=[[Cambridge, England|Cambridge]] |publisher=Cambridge University Press |title=Science & Civilisation in China, ''Vol. III:'' Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth |date=1959 |ref={{harvid|Needham & al.|1959}} |url=https://books.google.fr/books?id=jfQ9E0u4pLAC |author2=Wang Ling |display-authors=1 }}. |

|||

* {{citation |last=Pang-White |first=A. Ann |url=https://books.google.fr/books?id=EaRTDwAAQBAJ |title=The Confucian ''Four Books for Women'' |location=Oxford |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=2018 }}. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{citation |last=Zou |first=Hui |author-mask=[[Hui Zou|Zou Hui]] |url=https://books.google.fr/books?id=fD6p-LR_G7UC |title=A Jesuit Garden in Beijing and Early Modern Chinese Culture |date=2011 |publisher=Purdue University Press |location=[[West Lafayette, Indiana|West Lafayette]] }}. |

|||

== |

==Further Reading== |

||

* |

* {{citation |last= |first= |url=http://ctext.org/zhou-bi-suan-jing |title=《周髀算經》 |date= |location= |publisher=Chinese Text Project |lang=zh }}. |

||

* |

* {{citation |last= |first= |url=https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/12408 |title=《周髀算經》 |date= |location= |publisher=Project Gutenberg |lang=zh }}. |

||

* {{citation |author-link=Carl Benjamin Boyer|last=Boyer |first= Carl B. |title=A History of Mathematics |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |year=1991 |isbn=0-471-54397-7 }}. |

|||

* [[Christopher Cullen]]. ''Astronomy and Mathematics in Ancient China: The 'Zhou Bi Suan Jing''', Cambridge University Press, 2007. {{ISBN|0521035376}} |

|||

{{Han Dynasty topics}} |

{{Han Dynasty topics}} |

||

Revision as of 08:39, 30 December 2022

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (May 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Diagram added to the Zhoubi by Zhao Shuang | |||||||||

| Zhoubi Suanjing | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 《周髀算經》 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 《周髀算经》 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Zhoubi | |||||||||

| Chinese | 《周髀》 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | The Zhou Gnomon On Gnomons and Circular Paths | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Zhoubi | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 《算經》 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 《算经》 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | The Classic of Computation The Arithmetic Classic | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Zhoubi Suanjing, also known by many other names, is an ancient Chinese astronomical and mathematical work. The Zhoubi is most famous for its presentation of Chinese cosmology and a form of the Pythagorean theorem. It claims to present 246 problems worked out by the early Zhou culture hero Ji Dan and members of his court, placing its contents in the 11th century BC. However, the present form of the book does not seem to be earlier than the 2nd century Eastern Han, with some additions and commentaries continuing to be added for several more centuries.

Names

Zhoubi Suanjing is the atonal pinyin romanization of the modern standard Mandarin pronunciation of the work's Classical Chinese name, 《周髀算經》. The same name has been variously romanized as the Chou Pei Suan Ching',[1] the Tcheou-pi Souane,[2] &c. Its original title was simply the Zhoubi. The character 髀 is a literary term for the femur or thighbone but in context only refers to one or more gnomons, large sticks whose shadows were used for Chinese calendrical and astronomical calculations.[3] Because of the ambiguous nature of the character 周, it has been alternately understood and translated as "On the Gnomon and the Circular Paths of Heaven",[3] the Zhou Shadow Gauge Manual,[4] The Gnomon of the Zhou Sundial, [5] and Gnomon of the Zhou Dynasty.[6] The honorific Suanjing—Arithmetical Classic,[1] Sacred Book of Arithmetic,[7] Mathematical Canon,[6] Classic of Computations,[8] &c.—was added later.

Dating

Examples of the gnomon described in the work have been found from as early as 2300 BC and Ji Dan, better known as the Duke of Zhou, was an 11th century BC regent and noble during the first generation of the Zhou dynasty. The Zhoubi was traditionally dated to Ji Dan's own life[9] and considered to be the oldest Chinese mathematical treatise.[3] However, although some passages seem to come from the Warring States Period or earlier,[9] the current text of the work mentions Lü Bowei and is believed to have received its current form no earlier than the Eastern Han, during the 1st or 2nd century. It does not appear at all in the Book of Han's account of calendrical, astronomical, and mathematical works, although Joseph Needham allows that this may have been from its current contents having previously been provided in several different works listed in the Han history which are otherwise unknown.[3]

Contents

The Zhoubi is an anonymous collection of 246 problems[dubious ] encountered by the Duke of Zhou and figures in his court, including the astrologer Shang Gao (pinyin) or Kao (Wade-Giles). Each problem includes an answer and a corresponding arithmetic algorithm.

It is an important source on early Chinese cosmology, glossing the ancient idea of a round heaven over a square earth ({{lang|zh|天圆地方, tiānyuán dìfāng) as similar to the round parasol suspended over some ancient Chinese chariots[10] or a Chinese chessboard.[11] All things measurable were considered variants of the square, while the expansion of a polygon to infinite sides approaches the immeasurable circle.[4] This concept of a "canopy heaven" (蓋天, gàitiān) had earlier produced the jade bì (璧) and cóng (琮) objects and myths about Gonggong, Mount Buzhou, Nüwa, and repairing the sky. Although this eventually developed into an idea of a "spherical heaven" (渾天, hùntiān),[12] the Zhoubi offers numerous explorations of the geometric relationships of simple circles circumscribed by squares and squares circumscribed by circles.[13] A large part of this involves analysis of solar declination in the Northern Hemisphere at various points throughout the year.[3]

At one point during its discussion of the shadows cast by gnomons, the work presents a form of the Pythagorean theorem known as the gougu theorem (勾股定理, gōugǔ dìnglǐ)[14] from the Chinese names—lit. "hook" and "thigh"—of the two sides of the carpenter or try square.[15] In the 3rd century, Zhao Shuang's commentary on the Zhoubi included a diagram effectively proving the theorem[16] for the case of a 3-4-5 triangle,[17] whence it can be generalized to all right triangles. The original text being ambiguous on its own, there is disagreement as to whether this proof was established by Zhao or merely represented an illustration of a previously understood concept earlier than Pythagoras.[18][14] Shang Gao concludes the gougu problem saying "He who understands the earth is a wise man, and he who understands the heavens is a sage. Knowledge is derived from the shadow [straight line], and the shadow is derived from the gnomon [right angle]. The combination of the gnomon with numbers is what guides and rules the myriad things."[19]

Commentaries

The Zhoubi has had a prominent place in Chinese mathematics and was the subject of specific commentaries by Zhao Shuang in the 3rd century, Liu Hui in 263, by Zu Gengzhi in the early 6th century, Li Chunfeng in the 7th century, and Yang Hui in 1270.

See also

References

Citations

- ^ a b Needham & al. (1959), p. 815.

- ^ EB, 1st ed. (1771), p. 188.

- ^ a b c d e Needham & al. (1959), p. 19.

- ^ a b Zou (2011), p. 104.

- ^ Pang-White (2018), p. 464.

- ^ a b Cullen (2018), p. 758.

- ^ Davis & al. (1995), p. 28.

- ^ Elman (2015), p. 240.

- ^ a b Needham & al. (1959), p. 20.

- ^ Tseng (2011), pp. 45–49.

- ^ Ding (2020), p. 172.

- ^ Tseng (2011), p. 50.

- ^ Tseng (2011), p. 51.

- ^ a b Cullen (1996), p. 82.

- ^ Gamwell (2016), p. 39.

- ^ Cullen (1996), p. 208.

- ^ Chemla (2005), p. [page needed].

- ^ Chemla (2005).

- ^ Gamwell (2016), p. 41.

Works Cited

- "Chinese", Encyclopaedia Britannica, vol. II (1st ed.), Edinburgh: Colin Macfarquhar, 1771, pp. 184–192.

- Chemla, Karine (2005), Geometrical Figures and Generality in Ancient China and Beyond, Science in Context, ISBN 0-521-55089-0.

- Cullen, Christopher (1996), Astronomy and Mathematics in Ancient China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55089-0.

- Cullen, Christopher (2018), "Chinese Astronomy in the Early Imperial Age", The Cambridge History of Science, Vol. I: Ancient Science, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|editors-first2=ignored (help). - Davis, Philip J.; et al., eds. (1995), "Brief Chronological Table to 1910", The Mathematical Experience, Modern Birkhäuser Classics, Boston: Birkhäuser, pp. 26–29.

- Ding, Daniel D.X. (2020), The Historical Roots of Technical Communication in the Chinese Tradition, Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars.

- Elman, Benjamin (2015), "Early Modern or Late Imperial? The Crisis of Classical Philology in Eighteenth-Century China", Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 225–244

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help). - Gamwell, Lynn (2016), Mathematics + Art: A Cultural History, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Needham, Joseph; et al. (1959), Science & Civilisation in China, Vol. III: Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pang-White, A. Ann (2018), The Confucian Four Books for Women, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tseng, L.Y. Lillian (2011), Picturing Heaven in Early China, East Asian Monographs, Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, ISBN 978-0-674-06069-2.

- Zou Hui (2011), A Jesuit Garden in Beijing and Early Modern Chinese Culture, West Lafayette: Purdue University Press.

Further Reading

- 《周髀算經》 (in Chinese), Chinese Text Project.

- 《周髀算經》 (in Chinese), Project Gutenberg.

- Boyer, Carl B. (1991), A History of Mathematics, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-54397-7.