Sortition: Difference between revisions

Superb Owl (talk | contribs) →Political proposals for sortition: improving citations, removing poorly cited text to focus on well-sourced content |

Superb Owl (talk | contribs) →To select public officials: moving bullets to proper subsection, improving citations, removing additional external links in the text |

||

| Line 102: | Line 102: | ||

=== To select juries for specific issue(s) or policies === |

=== To select juries for specific issue(s) or policies === |

||

*Constitutional changes are one of the most common to solicit input via sortition. [[Etienne Chouard|Étienne Chouard]] advocates strongly that those seeking power (elected officials) should not write the rules, making sortition an essential choice for creating constitutions.<ref>{{Citation |title=Sortition as a sustainable protection against oligarchy |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KsnNpcJtwoo |language=en |access-date=2023-02-24}}. Talk by [[Etienne Chouard|Étienne Chouard]]. 0:43:03</ref> For example, the South Australian Constitutional Convention was a [[deliberative opinion poll]] created to consider changes to the state constitution. |

*Constitutional changes are one of the most common to solicit input via sortition. [[Etienne Chouard|Étienne Chouard]] advocates strongly that those seeking power (elected officials) should not write the rules, making sortition an essential choice for creating constitutions.<ref>{{Citation |title=Sortition as a sustainable protection against oligarchy |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KsnNpcJtwoo |language=en |access-date=2023-02-24}}. Talk by [[Etienne Chouard|Étienne Chouard]]. 0:43:03</ref> He also proposes replacing elections with bodies that use sortition to decide on key issues.<ref>{{cite web |date=August 24, 2012 |title="Populiste n'est pas un gros mot", entretien avec Etienne Chouard |trans-title="Populist is not a big word", interview with Etienne Chouard |url=http://ragemag.fr/populiste-nest-pas-un-gros-mot-entretien-avec-etienne-chouard |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120828182918/http://ragemag.fr/populiste-nest-pas-un-gros-mot-entretien-avec-etienne-chouard |archive-date=August 28, 2012 |website=Ragemag |language=fr}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=YouTube |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0e22oUvDSwM |website=www.youtube.com}}</ref> For example, the South Australian Constitutional Convention was a [[deliberative opinion poll]] created to consider changes to the state constitution. |

||

*Political scientist [[Robert A. Dahl]] suggests that an advanced democratic state could form groups which he calls minipopuli. Each group would consist of perhaps a thousand citizens randomly selected, and would either set an agenda of issues or deal with a particular major issue. It would hold hearings, commission research, and engage in debate and discussion. Dahl suggests having the minipopuli as supplementing, rather than replacing, legislative bodies.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dahl |first=Robert A. |title=Democracy and its Critics |pages=340}}</ref> |

*Political scientist [[Robert A. Dahl]] suggests that an advanced democratic state could form groups which he calls minipopuli. Each group would consist of perhaps a thousand citizens randomly selected, and would either set an agenda of issues or deal with a particular major issue. It would hold hearings, commission research, and engage in debate and discussion. Dahl suggests having the minipopuli as supplementing, rather than replacing, legislative bodies.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dahl |first=Robert A. |title=Democracy and its Critics |pages=340}}</ref> |

||

*Simon Threlkeld, in the 1998 journal article "A Blueprint for Democratic Law-Making: Give Citizen Juries the Final Say"<ref>{{cite journal |last=Threlkeld |first=Simon |date=Summer 1998 |title=A Blueprint for Democratic Law-Making: Give Citizen Juries the Final Say |url=https://equalitybylot.com/2015/11/06/threlkeld-juries-not-referenda/ |journal=Social Policy |pages=5–9 |via=Equality by Lot}} |

*Simon Threlkeld, in the 1998 journal article "A Blueprint for Democratic Law-Making: Give Citizen Juries the Final Say" proposes that laws be decided by legislative juries rather than by elected politicians or referendums.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Threlkeld |first=Simon |date=Summer 1998 |title=A Blueprint for Democratic Law-Making: Give Citizen Juries the Final Say |url=https://equalitybylot.com/2015/11/06/threlkeld-juries-not-referenda/ |journal=Social Policy |pages=5–9 |via=Equality by Lot}}</ref> The existing legislatures would continue to exist and could propose laws to legislative juries, but would no longer be able to pass laws. Citizens, public interest groups and others would also be able to propose laws to legislative juries. |

||

*L. León coined the word ''lottocracy'' for a sortition procedure that is somewhat different from [[John Burnheim|Burnheim's]] demarchy.<ref>{{Cite book |last=León |first=L |url=http://www.socsci.ru.nl/advdv/leonbook/leonbook.html |title=The World-Solution for World-Problems: The Problem, Its Cause, Its Solution |year=1988 |publisher=L. León |isbn=978-90-900259-2-6}}</ref> While "Burnheim ... insists that the random selection be made only from volunteers",<ref>{{cite magazine |author=Brian Martin |date=Fall 1992 |title=Demarchy: A Democratic Alternative to Electoral Politics |url=http://www.uow.edu.au/arts/sts/bmartin/pubs/92kio.html |url-status=dead |magazine=Kick It Over |pages=11–13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071228190617/http://www.uow.edu.au/arts/sts/bmartin/pubs/92kio.html |archive-date=December 28, 2007 |number=30}}</ref> León states "that first of all, the job must not be liked".<ref>[http://www.socsci.ru.nl/advdv/leonbook/node16.html The World Solution for World Problems, Chapter: A Concept for Government], León</ref> [[Christopher Frey]] uses the German term {{lang|de|Lottokratie}} and recommends testing lottocracy in town councils. Lottocracy, according to Frey, will improve the direct involvement of each citizen and minimize the systematical errors caused by [[political parties]] in [[Europe]].<ref>Christopher Frey (16 June 2009). ''Lottokratie: Entwurf einer postdemokratischen Gesellschaft''. Geschichte der Zukunft, volume 4. Books on Demand. {{ISBN|978-3-83-910540-5}}</ref> |

*L. León coined the word ''lottocracy'' for a sortition procedure that is somewhat different from [[John Burnheim|Burnheim's]] demarchy.<ref>{{Cite book |last=León |first=L |url=http://www.socsci.ru.nl/advdv/leonbook/leonbook.html |title=The World-Solution for World-Problems: The Problem, Its Cause, Its Solution |year=1988 |publisher=L. León |isbn=978-90-900259-2-6}}</ref> While "Burnheim ... insists that the random selection be made only from volunteers",<ref>{{cite magazine |author=Brian Martin |date=Fall 1992 |title=Demarchy: A Democratic Alternative to Electoral Politics |url=http://www.uow.edu.au/arts/sts/bmartin/pubs/92kio.html |url-status=dead |magazine=Kick It Over |pages=11–13 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071228190617/http://www.uow.edu.au/arts/sts/bmartin/pubs/92kio.html |archive-date=December 28, 2007 |number=30}}</ref> León states "that first of all, the job must not be liked".<ref>[http://www.socsci.ru.nl/advdv/leonbook/node16.html The World Solution for World Problems, Chapter: A Concept for Government], León</ref> [[Christopher Frey]] uses the German term {{lang|de|Lottokratie}} and recommends testing lottocracy in town councils. Lottocracy, according to Frey, will improve the direct involvement of each citizen and minimize the systematical errors caused by [[political parties]] in [[Europe]].<ref>Christopher Frey (16 June 2009). ''Lottokratie: Entwurf einer postdemokratischen Gesellschaft''. Geschichte der Zukunft, volume 4. Books on Demand. {{ISBN|978-3-83-910540-5}}</ref> |

||

*[[John Burnheim]] envisions a political system in which many small [[Citizens' juries|"citizens' juries"]] would deliberate and make decisions about public policies.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Burnheim |first=John |title=Is Democracy Possible?}}</ref> His proposal includes the dissolution of the state and of bureaucracies. The term demarchy he uses was coined by [[Friedrich Hayek]] for a different proposal,<ref>Friedrich August von Hayek: ''Law, legislation and liberty'', Volume 3, pp. 38–40.</ref> unrelated to sortition, and is now sometimes used to refer to any political system in which sortition plays a central role.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Burnheim |first1=John |title=Is Democracy Possible? |date=1985 |publisher=University of California Press |author-link=John Burnheim}}</ref> |

*[[John Burnheim]] envisions a political system in which many small [[Citizens' juries|"citizens' juries"]] would deliberate and make decisions about public policies.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Burnheim |first=John |title=Is Democracy Possible?}}</ref> His proposal includes the dissolution of the state and of bureaucracies. The term demarchy he uses was coined by [[Friedrich Hayek]] for a different proposal,<ref>Friedrich August von Hayek: ''Law, legislation and liberty'', Volume 3, pp. 38–40.</ref> unrelated to sortition, and is now sometimes used to refer to any political system in which sortition plays a central role.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Burnheim |first1=John |title=Is Democracy Possible? |date=1985 |publisher=University of California Press |author-link=John Burnheim}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | *Influenced by [[John Burnheim|Burnheim]], Marxist economists [[Paul Cockshott]] and Allin Cottrell propose that, to avoid formation of a new social elite in a post-capitalist society, "[t]he various organs of public authority would be controlled by citizens' committees chosen by lot" or partially chosen by lot.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Cockshott |first1=William Paul |title=Towards a New Socialism |title-link=Towards a New Socialism |last2=Cottrell |first2=Allin F. |publisher=[[Spokesman Books]] |year=1993 |isbn=978-0851245454 |author-link=Paul Cockshott}}</ref> |

||

*Claudia Chwalisz has advocated for using [[Citizens' assembly|citizens' assemblies]] selected by sortition to inform policy making on an ongoing basis.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Chwalisz |first=Claudia |title=The populist signal: why politics and democracy need to change |date=2015 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-1-78348-542-0 |location=London New York}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Chwalisz |first=Claudia |title=The People's Verdict: adding informed citizen voices to public decision-making |date=2017 |publisher=Policy Network/Rowman & Littlefield International |others=Policy Network |isbn=978-1-78660-436-1 |location=London New York}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=OECD |date=2021-12-14 |title=Eight ways to institutionalise deliberative democracy |series=OECD Public Governance Policy Papers |url=https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/eight-ways-to-institutionalise-deliberative-democracy_4fcf1da5-en |language=en |location=Paris |doi=10.1787/4fcf1da5-en|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Chwalisz |first=Claudia |date=2023-06-29 |title=Assembly required - RSA Comment |url=https://www.thersa.org/comment/2023/06/assembly-required |access-date=2023-07-16 |website=The RSA |language=en}}</ref> |

*Claudia Chwalisz has advocated for using [[Citizens' assembly|citizens' assemblies]] selected by sortition to inform policy making on an ongoing basis.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Chwalisz |first=Claudia |title=The populist signal: why politics and democracy need to change |date=2015 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-1-78348-542-0 |location=London New York}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Chwalisz |first=Claudia |title=The People's Verdict: adding informed citizen voices to public decision-making |date=2017 |publisher=Policy Network/Rowman & Littlefield International |others=Policy Network |isbn=978-1-78660-436-1 |location=London New York}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=OECD |date=2021-12-14 |title=Eight ways to institutionalise deliberative democracy |series=OECD Public Governance Policy Papers |url=https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/eight-ways-to-institutionalise-deliberative-democracy_4fcf1da5-en |language=en |location=Paris |doi=10.1787/4fcf1da5-en|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Chwalisz |first=Claudia |date=2023-06-29 |title=Assembly required - RSA Comment |url=https://www.thersa.org/comment/2023/06/assembly-required |access-date=2023-07-16 |website=The RSA |language=en}}</ref> |

||

=== To select public officials === |

=== To select public officials === |

||

*Simon Threlkeld |

*Simon Threlkeld proposed a wide range of public officials be chosen by randomly sampled juries, rather than by politicians or popular election.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Threlkeld |first=Simon |date=Summer 1997 |title=Democratizing Public Institutions: Juries for the selection of public officials |url=https://equalitybylot.com/2015/11/08/threlkeld-democratizing-public-institutions/ |journal=Humanist in Canada |issue=120 |pages=24–25, 33 |via=Equality by Lot}}</ref> As with "convened-sample suffrage", public officials are chosen by a random sample of the public from a relevant geographical area, such as a state governor being chosen by a random sample of citizens from that state. |

||

| ⚫ | *The introduction of a variable percentage of randomly selected independent legislators in a Parliament can increase the global efficiency of a legislature, in terms of both number of laws passed and average social welfare obtained<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pluchino |first=A. |last2=Garofalo |first2=C. |last3=Rapisarda |first3=A. |last4=Spagano |first4=S. |last5=Caserta |first5=M. |date=October 2011 |title=Accidental Politicians: How Randomly Selected Legislators Can Improve Parliament Efficiency |url=http://arxiv.org/abs/1103.1224 |journal=[[Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications]] |volume=390 |issue=21-22 |pages=3944–3954 |doi=10.1016/j.physa.2011.06.028}}</ref> (this work is consistent with a 2010 paper on how the adoption of random strategies can improve the efficiency of hierarchical organizations<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pluchino |first=Alessandro |last2=Rapisarda |first2=Andrea |last3=Garofalo |first3=Cesare |date=February 2010 |title=The Peter Principle Revisited: A Computational Study |url=http://arxiv.org/abs/0907.0455 |journal=[[Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications]] |volume=389 |issue=3 |pages=467–472 |doi=10.1016/j.physa.2009.09.045}}</ref>).<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Caserta |first1=Maurizio |last2=Pluchino |first2=Alessandro |last3=Rapisarda |first3=Andrea |last4=Spagano |first4=Salvatore |title=Why lot? How sortition could help representative democracy |journal=[[Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications]] |date=2021 |volume=565 |pages=125430 |doi=10.1016/j.physa.2020.125430|bibcode=2021PhyA..56525430C |s2cid=229495274 }}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | *Influenced by [[John Burnheim|Burnheim]], Marxist economists [[Paul Cockshott]] and Allin Cottrell propose that, to avoid formation of a new social elite in a post-capitalist society, "[t]he various organs of public authority would be controlled by citizens' committees chosen by lot" or partially chosen by lot.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Cockshott |first1=William Paul |title=Towards a New Socialism |title-link=Towards a New Socialism |last2=Cottrell |first2=Allin F. |publisher=[[Spokesman Books]] |year=1993 |isbn=978-0851245454 |author-link=Paul Cockshott}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | * |

||

*Michael Donovan proposes that the percentage of voters who do not turnout have their representatives chosen by sortition. For example, with 60% voter turnout a number of legislators are randomly chosen to make up 40% of the overall parliament.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Donovan |first1=Michael |url=http://summit.sfu.ca/item/12579 |title=Political Sortition for an Evolving World |date=2012 |publisher=Simon Fraser University |page=83}}</ref> |

*Michael Donovan proposes that the percentage of voters who do not turnout have their representatives chosen by sortition. For example, with 60% voter turnout a number of legislators are randomly chosen to make up 40% of the overall parliament.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Donovan |first1=Michael |url=http://summit.sfu.ca/item/12579 |title=Political Sortition for an Evolving World |date=2012 |publisher=Simon Fraser University |page=83}}</ref> |

||

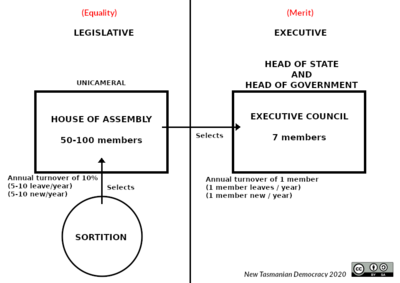

[[File:Sortition Tasmania.png|thumb|upright=1.8|right|Proposed changes to the legislature of the [[Parliament of Tasmania]]: A [[Unicameralism|single legislative body]] of 50–100 people is selected randomly from the population and makes laws. One of their duties is the selection of seven members of an [[Directorial system|executive council]] ]] |

[[File:Sortition Tasmania.png|thumb|upright=1.8|right|Proposed changes to the legislature of the [[Parliament of Tasmania]]: A [[Unicameralism|single legislative body]] of 50–100 people is selected randomly from the population and makes laws. One of their duties is the selection of seven members of an [[Directorial system|executive council]] ]] |

||

*[[C. L. R. James]]'s 1956 essay "Every Cook Can Govern" suggested to select, through sortition, a large legislative body (such as the U.S. Congress) from among the adult population at large.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/james-clr/works/1956/06/every-cook.htm |title=Every Cook Can Govern |first=C. L. R. |last=James |website=www.marxists.org}}</ref> |

*[[C. L. R. James]]'s 1956 essay "Every Cook Can Govern" suggested to select, through sortition, a large legislative body (such as the U.S. Congress) from among the adult population at large.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/james-clr/works/1956/06/every-cook.htm |title=Every Cook Can Govern |first=C. L. R. |last=James |website=www.marxists.org}}</ref> |

||

*[[Ernest Callenbach]] and [[Michael Phillips (consultant)|Michael Phillips]] |

*[[Ernest Callenbach]] and [[Michael Phillips (consultant)|Michael Phillips]] argued for random selection of the U.S. House of Representatives, arguing this would ensure fair representation for the people and their interests, an elimination of many [[realpolitik]] behaviors, and a reduction in the influence of money and associated corruption, all leading to better legislation.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Callenbach |first1=Ernest |url=http://www.well.com/~mp/citleg.html |title=A Citizen Legislature |last2=Phillips |first2=Michael |date=1985 |publisher=Banyan Tree Books / Clear Glass |location=Berkeley/Bodega California |author-link=Ernest Callenbach}}</ref> |

||

*[[Étienne Chouard]], a French political activist, proposes replacing elections with sortition.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ragemag.fr/populiste-nest-pas-un-gros-mot-entretien-avec-etienne-chouard |title="Populiste n'est pas un gros mot", entretien avec Etienne Chouard |language=fr |trans-title="Populist is not a big word", interview with Etienne Chouard |date=August 24, 2012 |website=Ragemag |url-status= dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120828182918/http://ragemag.fr/populiste-nest-pas-un-gros-mot-entretien-avec-etienne-chouard |archive-date=August 28, 2012 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0e22oUvDSwM |title=YouTube |website=www.youtube.com}}</ref> |

|||

*The House of Commons in both Canada<ref>{{cite news |last1=Mitchell |first1=Jack |last2=Mitchell |first2=David |date=22 September 2005 |title=Athens on the Hill: A plan for a Neo-Athenian Parliament in Canada |pages=A23 |publisher=National Post}}</ref> and the United Kingdom<ref>{{cite book |last1=Sutherland |first1=Keith |title=A People's Parliament |date=2008 |publisher=Imprint Academic}}</ref>, and/or the [[UK]] [[House of Lords]]<ref>{{cite book |last1=Barnett |first1=Anthony |title=The Athenian Option: Radical Reform for the House of Lords |last2=Carty |first2=Peter |date=2008 |publisher=Imprint Academic |edition=2nd}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=2015-08-18 |title=Let The People Wear Ermine If We Are to Abolish the House of Lords |url=http://www.disclaimermag.com/politics/let-the-people-wear-ermine-if-we-are-to-abolish-the-house-of-lords-2792 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160807170921/http://www.disclaimermag.com/politics/let-the-people-wear-ermine-if-we-are-to-abolish-the-house-of-lords-2792 |archivedate=2016-08-07 |website=Disclaimer}}</ref> have been proposed as providing an opportunity for sortition. |

*The House of Commons in both Canada<ref>{{cite news |last1=Mitchell |first1=Jack |last2=Mitchell |first2=David |date=22 September 2005 |title=Athens on the Hill: A plan for a Neo-Athenian Parliament in Canada |pages=A23 |publisher=National Post}}</ref> and the United Kingdom<ref>{{cite book |last1=Sutherland |first1=Keith |title=A People's Parliament |date=2008 |publisher=Imprint Academic}}</ref>, and/or the [[UK]] [[House of Lords]]<ref>{{cite book |last1=Barnett |first1=Anthony |title=The Athenian Option: Radical Reform for the House of Lords |last2=Carty |first2=Peter |date=2008 |publisher=Imprint Academic |edition=2nd}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=2015-08-18 |title=Let The People Wear Ermine If We Are to Abolish the House of Lords |url=http://www.disclaimermag.com/politics/let-the-people-wear-ermine-if-we-are-to-abolish-the-house-of-lords-2792 |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160807170921/http://www.disclaimermag.com/politics/let-the-people-wear-ermine-if-we-are-to-abolish-the-house-of-lords-2792 |archivedate=2016-08-07 |website=Disclaimer}}</ref> have been proposed as providing an opportunity for sortition. |

||

*Political science scholars Christoph Houman Ellersgaard, Anton Grau Larsen and Andreas Møller Mulvad of the [[Copenhagen Business School]] suggest supplementing the Danish parliament, the {{lang|da|italics=no|[[Folketing]]}}, with another chamber consisting of 300 randomly selected Danish citizens to combat elitism and career politicians, in their book {{lang|da|Tæm Eliten}} (''Tame the Elite'').<ref>{{Cite news |last1=Ellersgaard |first1=Christoph Houman |last2=Larsen |first2=Anton Grau |last3=Mulvad |first3=Andreas Møller |title=Centrum-venstre skal tøjle eliten og give borgerne større indflydelse |language=da-DK |work=Politiken |url=https://politiken.dk/debat/art6113441/Centrum-venstre-skal-t%C3%B8jle-eliten-og-give-borgerne-st%C3%B8rre-indflydelse |access-date=2018-04-15}}</ref> |

*Political science scholars Christoph Houman Ellersgaard, Anton Grau Larsen and Andreas Møller Mulvad of the [[Copenhagen Business School]] suggest supplementing the Danish parliament, the {{lang|da|italics=no|[[Folketing]]}}, with another chamber consisting of 300 randomly selected Danish citizens to combat elitism and career politicians, in their book {{lang|da|Tæm Eliten}} (''Tame the Elite'').<ref>{{Cite news |last1=Ellersgaard |first1=Christoph Houman |last2=Larsen |first2=Anton Grau |last3=Mulvad |first3=Andreas Møller |title=Centrum-venstre skal tøjle eliten og give borgerne større indflydelse |language=da-DK |work=Politiken |url=https://politiken.dk/debat/art6113441/Centrum-venstre-skal-t%C3%B8jle-eliten-og-give-borgerne-st%C3%B8rre-indflydelse |access-date=2018-04-15}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 05:21, 29 August 2023

| Part of the Politics series |

| Electoral systems |

|---|

|

|

|

In governance, sortition (also known as selection by lottery, selection by lot, allotment, demarchy, stochocracy, aleatoric democracy, democratic lottery, and lottocracy) is the selection of public officials or jurors using a random representative sample.[1][2][3] This minimizes factionalism, since those selected to serve can prioritize deliberating on the policy decisions in front of them instead of campaigning.[4] In ancient Athenian democracy, sortition was the traditional and primary method for appointing political officials, and its use was regarded as a principal characteristic of democracy.[5][6]

Today, sortition is commonly used to select prospective jurors in common-law systems. What has changed in recent years is the increased number of citizen groups with political advisory power,[7][8] along with calls for making sortition more consequential than elections, as it was in Athens, Venice and Florence.[9][10][11][12]

History

Ancient Athens

Athenian democracy developed in the 6th century BC out of what was then called isonomia (equality of law and political rights). Sortition was then the principal way of achieving this fairness. It was utilized to pick most[13] of the magistrates for their governing committees, and for their juries (typically of 501 men). Aristotle relates equality and democracy:

Democracy arose from the idea that those who are equal in any respect are equal absolutely. All are alike free, therefore they claim that all are free absolutely... The next is when the democrats, on the grounds that they are all equal, claim equal participation in everything.[14]

It is accepted as democratic when public offices are allocated by lot; and as oligarchic when they are filled by election.[15]

In Athens, "democracy" (literally meaning rule by the people) was in opposition to those supporting a system of oligarchy (rule by a few). Athenian democracy was characterised by being run by the "many" (the ordinary people) who were allotted to the committees which ran government. Thucydides has Pericles make this point in his Funeral Oration: "It is administered by the many instead of the few; that is why it is called a democracy."[16]

The Athenians believed sortition, not elections, to be democratic[13] and used complex procedures with purpose-built allotment machines (kleroteria) to avoid the corrupt practices used by oligarchs to buy their way into office. According to the author Mogens Herman Hansen, the citizen's court was superior to the assembly because the allotted members swore an oath which ordinary citizens in the assembly did not, therefore the court could annul the decisions of the assembly. Greek writers who mention democracy (including Aristotle,[13] Plato,[17] and Herodotus[18]) emphasize the role of selection by lot, or state outright that being allotted is more democratic than elections. David Van Reybrouck cites Aristotle as saying 'Voting by lot is in the nature of democracy; voting by choice is in the nature of aristocracy.'[19]

Past scholarship maintained that sortition had roots in the use of chance to divine the will of the gods, but this view is no longer common among scholars.[20] In Ancient Greek mythology, Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades used sortition to determine who ruled over which domain. Zeus got the sky, Poseidon the sea, and Hades the underworld.

In Athenian democracy, to be eligible to be chosen by lot, citizens self-selected themselves into the available pool, then lotteries in the kleroteria machines. The magistracies assigned by lot generally had terms of service of one year. A citizen could not hold any particular magistracy more than once in his lifetime, but could hold other magistracies. All male citizens over 30 years of age, who were not disenfranchised by atimia, were eligible. Those selected through lot underwent examination called dokimasia to avoid incompetent officials. Rarely were selected citizens discarded.[21] Magistrates, once in place, were subjected to constant monitoring by the Assembly. Magistrates appointed by lot had to render account of their time in office upon their leave, called euthynai. However, any citizen could request the suspension of a magistrate with due reason.[22]

A Kleroterion was used to select eligible and willing citizens to serve jury duty. This bolstered the initial Athenian system of democracy by getting new and different jury members from each tribe to avoid corruption.[23] James Wycliffe Headlam explains that the Athenian Council (500 administrators randomly selected), would commit occasional mistakes such as levying taxes that were too high. Headlam found minor instances of corruption but deemed systematic oppression and organized fraud as impossible given widely distributed power as well as checks-and-balances.[24] Furthermore, power did not necessarily go to those who wanted it and had schemed for it. The Athenians used an intricate machine, a kleroterion, to allot officers. Headlam found the Athenians felt no distrust of the system of random selection, but regarded it as the most natural and the simplest way of appointment.[25] While sortition was used for 90% of positions, elections were sometimes used for positions like for military commanders (strategos).[26] According to Xenophon (Memorabilia Book I, 2.9), Socrates[27] and Isocrates[28] critiqued sortition, questioning whether randomly-selected decision-makers had enough expertise.

Lombardy and Venice – 12th to 18th century

The brevia was used in the city states of Lombardy during the 12th and 13th centuries and in Venice until the late 18th century.[29] Men, who were chosen randomly, swore an oath that they were not acting under bribes, and then they elected members of the council. Voter and candidate eligibility probably included property owners, councilors, guild members, and perhaps, at times, artisans. The Doge of Venice was determined through a complex process of nomination, voting and sortition.

Lot was used in the Venetian system only in order to select members of the committees that served to nominate candidates for the Great Council. A combination of election and lot was used in this multi-stage process. Lot was not used alone to select magistrates, unlike in Florence and Athens. The use of lot to select nominators made it more difficult for political sects to exert power, and discouraged campaigning.[21] By reducing intrigue and power moves within the Great Council, lot maintained cohesiveness among the Venetian nobility, contributing to the stability of this republic. Top magistracies generally still remained in the control of elite families.[30]

Florence – 14th and 15th century

Scrutiny was used in Florence for over a century starting in 1328.[29] Nominations and voting together created a pool of candidates from different sectors of the city. The names of these men were deposited into a sack, and a lottery draw determined who would get to be a magistrate. The scrutiny was gradually opened up to minor guilds, reaching the greatest level of Renaissance citizen participation in 1378–1382.

In Florence, lot was used to select magistrates and members of the Signoria during republican periods. Florence utilized a combination of lot and scrutiny by the people, set forth by the ordinances of 1328.[21] In 1494, Florence founded a Great Council in the model of Venice. The nominatori were thereafter chosen by lot from among the members of the Great Council, indicating a decline in aristocratic power.[31]

The Enlightenment

During the Age of Enlightenment, many of the political ideals originally championed by the democratic city-states of ancient Greece were revisited. The use of sortition as a means of selecting the members of government while receiving praise from notable Enlightenment thinkers, received almost no discussion during the formation of the American and French republics.

Montesquieu, for example, whose classic work The Spirit of Laws is often quoted in support of sortition, provides one of the most direct discussions of the concept in Enlightenment political writing. "The suffrage by lot," he argues, "is natural to democracy; as that by choice is to aristocracy."[32] In making this statement about the democratic nature of sortition, Montesquieu echoes the philosophy of much earlier thinkers such as Aristotle, who also viewed election as aristocratic.[33] Montesquieu caveats his support by saying that there should also be some mechanisms to ensure the pool of selection is competent and not corrupt.[34] Rousseau also found that a mixed model of sortition and election provided a healthier path for democracy than one or the other.[35] Harrington, also found the Venetian model of sortition compelling, recommending it for his ideal republic of Oceana.[36] Edmund Burke, in contrast, worried that those randomly selected to serve would be less effective and productive than self-selected politicians.[21][37][38]

Bernard Manin, a French political theorist, points out the surprising nature of sortition's decline during the Enlightenment in his 1997 book The Principles of Representative Government. "What is indeed astonishing," he says, "in the light of the republican tradition and the theorizing it had generated, is the total absence of debate in the early years of representative government about the use of lot in the allocation of power." There are several possible explanations as to what forces caused this demonstrated disinterest in the use of sortition in modern government. The first potential explanation that Manin offers is that the choosing of rulers by lot may have been viewed as impractical on such a large scale as the modern state. A second possible explanation given is that elections provided greater political consent than sortition.[33]

However, David Van Reybrouck finds the following two reasons for this period's recession of sortition more compelling than Manin's:[39]

1) The relatively limited knowledge about Athenian democracy, with the first thorough examination coming only in 1891 with Election by Lot at Athens.

2) Wealthy enlightenment figures preferred to retain more power by holding elections, with most not even offering excuses on the basis of practicality but plainly saying they preferred to retain significant elite power.

He also quotes commentators of 18th century France and the United States arguing that they simply dislodged a hereditary aristocracy to replace it with an elected aristocracy.[40]

Switzerland

Because financial gain could be achieved through the position of mayor, some parts of Switzerland used random selection during the years between 1640 and 1837 to prevent corruption.[41]

India

Local government in parts of Tamil Nadu such as the village of Uttiramerur traditionally used a system known as kuda-olai where the names of candidates for the village committee were written on palm leaves and put into a pot and pulled out by a child.[42]

Methods

Before the random selection can be done, the pool of candidates must be defined. Systems vary as to whether they allot from eligible volunteers, from those screened by education, experience, or a passing grade on a test, or screened by election by those selected by a previous round of random selection, or from the membership or population at large. A multi-stage process in which random selection is alternated with other screening methods can be used, as in the Venetian system.

One robust, general, public method of allotment in use since 1997 is documented in RFC 3797: Publicly Verifiable Nominations Committee Random Selection. Using it, multiple specific sources of random numbers (e.g., lotteries) are selected in advance, and an algorithm is defined for selecting the winners based on those random numbers. When the random numbers become available, anyone can calculate the winners.[citation needed] David Chaum proposed Random-Sample Elections in 2012. Via recent advances in computer science, it is now possible to select a random sample of eligible voters in a verifiably valid manner and empower them to study and make a decision on a matter of public policy. This can be done in a highly transparent manner which allows anyone to verify the integrity of the election, while optionally preserving the anonymity of the voters.[43] A related approach has been pioneered by James Fishkin, director of the Deliberative Democracy Lab at Stanford, to make legally binding decisions in Greece, China and other countries.[44]

Analysis

A critique of electoral politics is the over-representation of politically active groups in society who tend to be those who join political parties.[45][26] For example, in 2000 less than 2%[46] of the UK population belonged to a political party, while in 2005 there were at best only 3 independent MPs (see List of UK minor party and independent MPs elected) so that 99.5% of all UK MPs belonged to a political party. Cognitive diversity is an amalgamation of different ways of seeing the world and interpreting events within it,[47] where a diversity of perspectives and heuristics guide individuals to create different solutions to the same problems.[48] Cognitive diversity is not the same as gender, ethnicity, value-set or age diversity, although they are often positively correlated. According to numerous scholars such as Page and Landemore,[49] cognitive diversity is more important to creating successful ideas than the average ability level of a group. This "diversity trumps ability theorem"[50] is essential to why sortition is a viable democratic option.[48] Simply put, random selection of persons of average intelligence performs better than a collection of the best individual problem solvers.[48]

Magnus Vinding in his book Reasoned Politics argues that sortition is more efficient by allowing decision-makers to focus on positive-sum endeavors rather than zero-sum elections.[51] This shift towards issues and away from elections could help to lessen political polarization[51] and the influence of money and interest-groups in politics.[40]

A modern advocate of sortition, political scientist John Burnheim, notes the importance of legitimacy for the effectiveness of the practice.[52] Legitimacy does depend on the success in achieving representativeness, which if not met, could limit the use cases of sortition to serving as consultative or political agenda-setting bodies.[53] Oliver Dowlen points to the egalitarian nature of all citizens having an equal chance of entering office irrespective of any bias in society that appear in representative bodies that can make them more representative.[54][55] To bolster legitimacy, other sortition bodies have been used and proposed to set the rules to improve accountability without the need for elections.[56]

As participants grow in competence by contributing to deliberation, they also become more engaged and interested in civic affairs.[57] Most societies have some type of citizenship education, but sortition-based committees allow ordinary people to develop their own democratic capacities through direct participation.[58]

Modern application

Sortition is most commonly used to form citizens' assemblies. The OECD has counted almost 600 examples of citizens' assemblies with members selected by lottery for public decision making.[59] As an example, Vancouver council initiated a citizens' assembly that met in 2014–15 in order to assist in city planning.[60]

Sortition is commonly used in selecting juries in Anglo-Saxon legal systems and in small groups (e.g., picking a school class monitor by drawing straws). In public decision-making, individuals are often determined by allotment if other forms of selection such as election fail to achieve a result. Examples include certain hung elections and certain votes in the UK Parliament. Some contemporary thinkers like David Van Reybrouck have advocated a greater use of selection by lot in today's political systems. The international non-profit and non-partisan research and action institute DemocracyNext, founded by Claudia Chwalisz, advocates for citizens' assemblies with members selected by sortition to become the defining institutions of a next democratic paradigm.

Sortition is also used in military conscription, as one method of awarding US green cards, and in placing students into some schools.[61]

Non-governmental organizations

Sortition also has potential for helping large associations to govern themselves democratically without the use of elections. Co-ops, employee-owned businesses, housing associations, Internet platforms, student governments, and countless other large membership organizations whose members generally do not know many other members yet seek to run their organization democratically often find elections problematic. The essential leadership decisions are made by the nomination process, often generating a self-perpetuating board whose nominating committee selects their own successors. Randomly selecting a representative sample of members to constitute a nominating panel is one procedure that has been proposed to keep fundamental control in the hands of ordinary members and avoid internal board corruption.[62] For example, The Samaritan Ministries Health Plan sometimes uses a panel of 13 randomly selected members to resolve disputes, which sometimes leads to policy changes.[63] Also, Democracy In Practice, an international organization dedicated to democratic innovation, experimentation and capacity-building, has implemented sortition in schools in Bolivia, replacing student government elections with lotteries.[64] Lastly, in 2013 the New Zealand Health Research council began awarding funding at random to applicants considered equally qualified.[65]

Public policy

Perhaps the most common example in practice today, are law court juries which are formed through sortition in some countries, such as the United States and United Kingdom. An increasingly common set of examples includes Citizens' assemblies, which have been used to provide input to policy makers all across the globe, including in countries like Ireland and Denmark. The selection of citizens may not be perfectly random, but still aims to be representative.

There are numerous examples of permanent or ongoing citizens' assemblies.[66] In 2019, the German speaking Ostbelgien region in Belgium, implemented the Ostbelgien Model, consisting of an 24-member Citizen's Council which convenes short term Citizen's Assemblies to provide non-binding recommendations to its parliament.[67] Later that same year both the main and French-speaking parliaments of the Brussels-Capital Region voted to authorize setting up mixed parliamentary committees composed of parliamentarians and randomly selected citizens to draft recommendations on a given issue.[68] The permanent Paris Citizens' Assembly was established in 2021, and the permanent Brussels Citizens' Assembly on Climate was established in 2022.

At a subnational level, the Amish use sortition applied to a slate of nominees when they select their community leaders. In their process, formal members of the community each register a single private nomination, and candidates with a minimum threshold of nominations then stand for the random selection that follows.[69] In 2015 the city of Utrecht randomly invited 10,000 residents, of whom 900 responded and 165 were eventually chosen, to participate in developing its 2016 energy and climate plan.[70][71]

Following the 1978 Meghalaya Legislative Assembly election, due to disagreements amongst the parties of the governing coalition, the Chief Minister's position was chosen by drawing lots.[72] In 2004, a randomly selected group of citizens in British Columbia convened to propose a new electoral system. This Citizens' Assembly on Electoral Reform was repeated three years later in Ontario's citizens' assembly.

Inspired by the work of the Citizens' Assemblies on Electoral Reform, MASS LBP has pioneered the use of Citizens' Reference Panels for addressing a range of policy issues for public sector. The Reference Panels use civic lotteries, a modern form of sortition, to randomly select citizen-representatives from the general public.[73][74] A similar initiative pioneered in the United States, the Citizens' Initiative Review, also uses a sortition based panel of citizen voters to review and comment on ballot initiative measures. The selection process utilizes random and stratified sampling techniques to create a representative 24-person panel which deliberates in order to summarize the measure in question.[75]

Political proposals for sortition

To select juries for specific issue(s) or policies

- Constitutional changes are one of the most common to solicit input via sortition. Étienne Chouard advocates strongly that those seeking power (elected officials) should not write the rules, making sortition an essential choice for creating constitutions.[76] He also proposes replacing elections with bodies that use sortition to decide on key issues.[77][78] For example, the South Australian Constitutional Convention was a deliberative opinion poll created to consider changes to the state constitution.

- Political scientist Robert A. Dahl suggests that an advanced democratic state could form groups which he calls minipopuli. Each group would consist of perhaps a thousand citizens randomly selected, and would either set an agenda of issues or deal with a particular major issue. It would hold hearings, commission research, and engage in debate and discussion. Dahl suggests having the minipopuli as supplementing, rather than replacing, legislative bodies.[79]

- Simon Threlkeld, in the 1998 journal article "A Blueprint for Democratic Law-Making: Give Citizen Juries the Final Say" proposes that laws be decided by legislative juries rather than by elected politicians or referendums.[80] The existing legislatures would continue to exist and could propose laws to legislative juries, but would no longer be able to pass laws. Citizens, public interest groups and others would also be able to propose laws to legislative juries.

- L. León coined the word lottocracy for a sortition procedure that is somewhat different from Burnheim's demarchy.[81] While "Burnheim ... insists that the random selection be made only from volunteers",[82] León states "that first of all, the job must not be liked".[83] Christopher Frey uses the German term Lottokratie and recommends testing lottocracy in town councils. Lottocracy, according to Frey, will improve the direct involvement of each citizen and minimize the systematical errors caused by political parties in Europe.[84]

- John Burnheim envisions a political system in which many small "citizens' juries" would deliberate and make decisions about public policies.[85] His proposal includes the dissolution of the state and of bureaucracies. The term demarchy he uses was coined by Friedrich Hayek for a different proposal,[86] unrelated to sortition, and is now sometimes used to refer to any political system in which sortition plays a central role.[87]

- Influenced by Burnheim, Marxist economists Paul Cockshott and Allin Cottrell propose that, to avoid formation of a new social elite in a post-capitalist society, "[t]he various organs of public authority would be controlled by citizens' committees chosen by lot" or partially chosen by lot.[88]

- Claudia Chwalisz has advocated for using citizens' assemblies selected by sortition to inform policy making on an ongoing basis.[89][90][91][92]

To select public officials

- Simon Threlkeld proposed a wide range of public officials be chosen by randomly sampled juries, rather than by politicians or popular election.[93] As with "convened-sample suffrage", public officials are chosen by a random sample of the public from a relevant geographical area, such as a state governor being chosen by a random sample of citizens from that state.

- The introduction of a variable percentage of randomly selected independent legislators in a Parliament can increase the global efficiency of a legislature, in terms of both number of laws passed and average social welfare obtained[94] (this work is consistent with a 2010 paper on how the adoption of random strategies can improve the efficiency of hierarchical organizations[95]).[96]

- Michael Donovan proposes that the percentage of voters who do not turnout have their representatives chosen by sortition. For example, with 60% voter turnout a number of legislators are randomly chosen to make up 40% of the overall parliament.[97]

- C. L. R. James's 1956 essay "Every Cook Can Govern" suggested to select, through sortition, a large legislative body (such as the U.S. Congress) from among the adult population at large.[98]

- Ernest Callenbach and Michael Phillips argued for random selection of the U.S. House of Representatives, arguing this would ensure fair representation for the people and their interests, an elimination of many realpolitik behaviors, and a reduction in the influence of money and associated corruption, all leading to better legislation.[99]

- The House of Commons in both Canada[100] and the United Kingdom[101], and/or the UK House of Lords[102][103] have been proposed as providing an opportunity for sortition.

- Political science scholars Christoph Houman Ellersgaard, Anton Grau Larsen and Andreas Møller Mulvad of the Copenhagen Business School suggest supplementing the Danish parliament, the Folketing, with another chamber consisting of 300 randomly selected Danish citizens to combat elitism and career politicians, in their book Tæm Eliten (Tame the Elite).[104]

- Terry Bouricius, a former Vermont legislator and political scientist, proposes in a 2013 journal article how a democracy could function better without elections, through the use of many randomly selected bodies, each with a defined role.[37]

- In his 2017 presidential election platform, French politician Jean-Luc Mélenchon of La France Insoumise lays out a proposal for a sixth republic.[105] The upper house of this republic would be formed through national sortition. Additionally, the constituent assembly to create this republic would have 50% of its members chosen in this way, with the remainder being elected.[106]

- Adam Grant published a 2023 op-ed citing findings by Alexander Haslam showing more altruism in randomly-selected decision-makers as well as other studies showing an overrepresentation of psychopathic and narcissistic traits in elected officials.[107]

See also

- Citizens' assembly

- Deliberative democracy

- Jury selection

- Political egalitarianism

- Solar Lottery, a 1955 science fiction novel by Philip K. Dick involving sortition

- Wisdom of the crowd

References

- ^ Engelstad, Fredrik (1989). "The assignment of political office by lot". Social Science Information. 28 (1): 23–50. doi:10.1177/053901889028001002. S2CID 144352457.

- ^ OECD (2020). Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. doi:10.1787/339306da-en. ISBN 9789264837621. S2CID 243747068.

- ^ Landemore, Hélène (January 15, 2010). Deliberation, Representation, and the Epistemic Function of Parliamentary Assemblies: a Burkean Argument in Favor of Descriptive Representation (PDF). International Conference on "Democracy as Idea and Practice", University of Oslo, Oslo January 13–15, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 8, 2013.

- ^ Graeber, David (April 9, 2013). The Democracy Project: A History, a Crisis, a Movement. Random House Inc. pp. 957–959. ISBN 978-0-679-64600-6. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ Headlam, James Wycliffe (1891). Election by Lot at Athens. The University Press. p. 12.

- ^ Cambiano, Giuseppe (2020). "Piccola archeologia del sorteggio". Teoria Politica (in Italian) (10): 103–121.

- ^ Flanigan, Bailey; Gölz, Paul; Gupta, Anupam; Hennig, Brett; Procaccia, Ariel D. (2021). "Fair algorithms for selecting citizens' assemblies". Nature. 596 (7873): 548–552. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..548F. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03788-6. PMC 8387237. PMID 34349266.

- ^ Fishkin, James (2009). When the People Speak: Deliberative Democracy & Public Consultation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199604432.

- ^ Ostfeld, Jacob (November 19, 2020). "The Case for Sortition in America". Harvard Political Review. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ Reybrouck, David Van (June 29, 2016). "Why elections are bad for democracy". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ Rieg, Timo; Translated from German by Catherine McLean (September 8, 2015). "Why a citizen's parliament chosen by lot would be 'perfect'". SWI swissinfo.ch (Op-ed.). Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ Wolfson, Arthur M. (1899). "The Ballot and Other Forms of Voting in the Italian Communes". The American Historical Review. 5 (1): 1–21. doi:10.2307/1832957. JSTOR 1832957.

- ^ a b c The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes, Mogens Herman Hansen, ISBN 1-85399-585-1

- ^ Aristotle, Politics 1301a28-35

- ^ Aristotle, Politics 4.1294be

- ^ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War. The Funeral Oration of Pericles.

- ^ Plato, Republic VIII, 557a

- ^ Herodotus The Histories 3.80.6

- ^ Reybrouck, David van (2016). Against elections: the case for democracy. Translated by Waters, Liz. London: The Bodley Head. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-84792-422-3.

- ^ Bernard Manin, The Principles of Representative Government

- ^ a b c d Manin, Bernard (1997). The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45891-7.

- ^ Hansen, M. H. (1981). Election by Lot at Athens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Dibble, Julian. "Info Tech of Ancient Democracy". Alamut.

- ^ Headlam, James Wycliffe (1891). Election by Lot at Athens. The University Press. p. 77.

- ^ Headlam, James Wycliffe (1891). Election by Lot at Athens. The University Press. p. 96.

- ^ a b Tangian, Andranik (2020). "Chapter 1 Athenian democracy″ and ″Chapter 6 Direct democracy". Analytical theory of democracy. Vols. 1 and 2. Studies in Choice and Welfare. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. pp. 3–43, 263–315. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-39691-6. ISBN 978-3-030-39690-9. S2CID 216190330.

- ^ Xenophon. Memorabilia Book I, 2.9

- ^ Isocrates. Areopagiticus (section 23)

- ^ a b Dowlen, Oliver (2008). The Political Potential of Sortition: A study of the random selection of citizens for public office. Imprint Academic.

- ^ Rousseau (1762). On the Social Contract. New York: St Martin's Press. p. 112.

- ^ Brucker, Gene (1962). Florentine Politics and Society 1342–1378. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Montesquieu (2001) [1748]. De l'esprit des lois [The Spirit of Laws]. Translated by Nugent, Thomas. Batoche Books, Kitchener.

- ^ a b Manin, Bernard (1997). The principles of representative government. Cambridge. ISBN 978-1-4619-4910-7. OCLC 861693063.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Manin, Bernard (1997). The principles of representative government. Cambridge. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4619-4910-7. OCLC 861693063.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Van Reybrouck, David (2016). Against elections : the case for democracy. Kofi A. Annan, Liz Waters (First US ed.). New York. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-1-60980-811-2. OCLC 1029781182.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Manin, Bernard (1997). The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4619-4910-7. OCLC 861693063.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Bouricius, Terrill (April 30, 2013). "Democracy Through Multi-Body Sortition: Athenian Lessons for the Modern Day". Journal of Public Deliberation. 9 (1). doi:10.16997/jdd.156.

- ^ Edmund Burke (1790), Reflections on the Revolution in France

- ^ Van Reybrouck, David (2016). Against Elections: the case for democracy. Seven Stories Press. pp. 75–78. ISBN 978-1-60980-811-2. OCLC 1048327708.

- ^ a b Reybrouck, David van (2016). Against elections: the case for democracy. Translated by Waters, Liz. London: The Bodley Head. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-84792-422-3.

- ^ Carson, Lyn; Martin, Brian (1999). Random Selection in Politics. Praeger. p. 33.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Hinduism". Encyclopedia of Hinduism.

- ^ David Chaum (2012). "Random-Sample Elections: Far lower cost, better quality and more democratic" (PDF). Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ Davis, Joshua (May 16, 2012). "How Selecting Voters Randomly Can Lead to Better Elections". Wired. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ Tangian, Andranik (2008). "A mathematical model of Athenian democracy". Social Choice and Welfare. 31 (4): 537–572. doi:10.1007/s00355-008-0295-y. S2CID 7112590.

- ^ Tom Bentley; Paul Miller (September 24, 2004). "The decline of the political party". perfect.co.uk. Archived from the original on October 10, 2006. Retrieved October 25, 2006.

- ^ Landemore, Hélène (2012). "Deliberation, Cognitive Diversity, and Democratic Inclusiveness: An Epistemic Argument for the Random Selection of Representatives". Synthese. 190 (7): 1209–1231. doi:10.1007/s11229-012-0062-6. S2CID 21572876.

- ^ a b c Page (2007). How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools, and societies. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Bouricious, Terrill (2013). "Democracy Through Multi-Body Sortition: Athenian Lessons for the Modern Day". Journal of Public Deliberation. 9 (1). Article 11. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ Dreifus, Claudia (January 8, 2008). "In Professor's Model, Diversity = Productivity". New York Times. Retrieved June 4, 2019.

- ^ a b Vinding, Magnus (2022). "14: Democracy". Reasoned Politics. Copenhagen: Ratio Ethica. pp. 225–226. ISBN 9798790852930.

- ^ Burnheim, John (2006). Is Democracy Possible?. University of California Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-1920898427.

- ^ Lafont, Cristina (March 1, 2015). "Deliberation, Participation, and Democratic Legitimacy: Should Deliberative Mini-publics Shape Public Policy?". Journal of Political Philosophy. 23 (1): 40–63. doi:10.1111/jopp.12031. ISSN 1467-9760.

- ^ Delannoi, Gil; Dowlen, Oliver (October 5, 2016). Sortition: Thoery and Practice. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-84540-700-1.

- ^ Dowlen, Oliver (June 2009). "Sorting Out Sortition: A Perspective on the Random Selection of Political Officers". Political Studies. 57 (2): 298–315. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2008.00746.x. ISSN 0032-3217. S2CID 144381781.

- ^ Manin, Bernard (1997). The principles of representative government. Cambridge. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4619-4910-7. OCLC 861693063.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Sortition as a sustainable protection against oligarchy, retrieved February 24, 2023. Talk by Étienne Chouard. At 0:17:10

- ^ Zaphir, Luke (2017). "Democratic communities of inquiry: Creating opportunities to develop citizenship". Educational Philosophy and Theory. 50 (4): 359–368. doi:10.1080/00131857.2017.1364156. S2CID 149151121.

- ^ OECD (2020). Innovative Citizen Participation and New Democratic Institutions: Catching the Deliberative Wave. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. doi:10.1787/339306da-en. ISBN 9789264837621. S2CID 243747068.

- ^ "City of Vancouver Grandview-Woodland Community Plan". Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Boyle, Conall (2010). Lotteries for Education. Exeter: Imprint Academic.

- ^ Terry Bouricius (April 19, 2017). "A Better Co-op Democracy Without Elections?". P2P Foundation.

- ^ Leonard, Kimberly (February 23, 2016). "Christians Find Their Own Way to Replace Obamacare". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved March 22, 2016.

- ^ "Participedia, Democracy In Practice: Democratic Student Government Program". Participedia. February 2014.

- ^ Liu M, Choy V, Clarke P, Barnett A, Blakely T, Pomeroy L (2020). "The acceptability of using a lottery to allocate research funding: a survey of applicants". Res Integr Peer Rev. 5: 3. doi:10.1186/s41073-019-0089-z. PMC 6996170. PMID 32025338.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ OECD (December 14, 2021). "Eight ways to institutionalise deliberative democracy". OECD Public Governance Policy Papers. Paris. doi:10.1787/4fcf1da5-en.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The Ostbelgien Model: a long-term Citizens' Council combined with short-term Citizens' Assemblies".

- ^ "Belgium's experiment in permanent forms of deliberative democracy".

- ^ B., Kraybill, Donald (2013). The Amish. Johnson-Weiner, Karen., Nolt, Steven M., 1968–. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9781421409146. OCLC 810329297.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Utrecht, an energy plan devised by citizens".

- ^ Meijer, Albert; Van Der Veer, Reinout; Faber, Albert; Penning De Vries, Julia (2017). "Political innovation as ideal and strategy: the case of aleatoric democracy in the City of Utrecht". Public Management Review. 19: 20–36. doi:10.1080/14719037.2016.1200666. hdl:1765/108549. S2CID 156169727.

- ^ Staff (November 18, 2008). "Former Meghalaya Chief Minister D D Pugh dies". Oneindia.com. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ "Sorted: Civic Lotteries and the Future of Public Participation". People Powered. 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ "How to run a Civic Lottery: Designing fair selection mechanisms for deliberative public processes". People Powered. July 21, 2020. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ^ Davis, Linn (2017). "Citizens' Initiative Review". Healthy Democracy.

- ^ Sortition as a sustainable protection against oligarchy, retrieved February 24, 2023. Talk by Étienne Chouard. 0:43:03

- ^ ""Populiste n'est pas un gros mot", entretien avec Etienne Chouard" ["Populist is not a big word", interview with Etienne Chouard]. Ragemag (in French). August 24, 2012. Archived from the original on August 28, 2012.

- ^ "YouTube". www.youtube.com.

- ^ Dahl, Robert A. Democracy and its Critics. p. 340.

- ^ Threlkeld, Simon (Summer 1998). "A Blueprint for Democratic Law-Making: Give Citizen Juries the Final Say". Social Policy: 5–9 – via Equality by Lot.

- ^ León, L (1988). The World-Solution for World-Problems: The Problem, Its Cause, Its Solution. L. León. ISBN 978-90-900259-2-6.

- ^ Brian Martin (Fall 1992). "Demarchy: A Democratic Alternative to Electoral Politics". Kick It Over. No. 30. pp. 11–13. Archived from the original on December 28, 2007.

- ^ The World Solution for World Problems, Chapter: A Concept for Government, León

- ^ Christopher Frey (16 June 2009). Lottokratie: Entwurf einer postdemokratischen Gesellschaft. Geschichte der Zukunft, volume 4. Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-83-910540-5

- ^ Burnheim, John. Is Democracy Possible?.

- ^ Friedrich August von Hayek: Law, legislation and liberty, Volume 3, pp. 38–40.

- ^ Burnheim, John (1985). Is Democracy Possible?. University of California Press.

- ^ Cockshott, William Paul; Cottrell, Allin F. (1993). Towards a New Socialism. Spokesman Books. ISBN 978-0851245454.

- ^ Chwalisz, Claudia (2015). The populist signal: why politics and democracy need to change. London New York: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-78348-542-0.

- ^ Chwalisz, Claudia (2017). The People's Verdict: adding informed citizen voices to public decision-making. Policy Network. London New York: Policy Network/Rowman & Littlefield International. ISBN 978-1-78660-436-1.

- ^ OECD (December 14, 2021). "Eight ways to institutionalise deliberative democracy". OECD Public Governance Policy Papers. Paris. doi:10.1787/4fcf1da5-en.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Chwalisz, Claudia (June 29, 2023). "Assembly required - RSA Comment". The RSA. Retrieved July 16, 2023.

- ^ Threlkeld, Simon (Summer 1997). "Democratizing Public Institutions: Juries for the selection of public officials". Humanist in Canada (120): 24–25, 33 – via Equality by Lot.

- ^ Pluchino, A.; Garofalo, C.; Rapisarda, A.; Spagano, S.; Caserta, M. (October 2011). "Accidental Politicians: How Randomly Selected Legislators Can Improve Parliament Efficiency". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 390 (21–22): 3944–3954. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2011.06.028.

- ^ Pluchino, Alessandro; Rapisarda, Andrea; Garofalo, Cesare (February 2010). "The Peter Principle Revisited: A Computational Study". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 389 (3): 467–472. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2009.09.045.

- ^ Caserta, Maurizio; Pluchino, Alessandro; Rapisarda, Andrea; Spagano, Salvatore (2021). "Why lot? How sortition could help representative democracy". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 565: 125430. Bibcode:2021PhyA..56525430C. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2020.125430. S2CID 229495274.

- ^ Donovan, Michael (2012). Political Sortition for an Evolving World. Simon Fraser University. p. 83.

- ^ James, C. L. R. "Every Cook Can Govern". www.marxists.org.

- ^ Callenbach, Ernest; Phillips, Michael (1985). A Citizen Legislature. Berkeley/Bodega California: Banyan Tree Books / Clear Glass.

- ^ Mitchell, Jack; Mitchell, David (September 22, 2005). "Athens on the Hill: A plan for a Neo-Athenian Parliament in Canada". National Post. pp. A23.

- ^ Sutherland, Keith (2008). A People's Parliament. Imprint Academic.

- ^ Barnett, Anthony; Carty, Peter (2008). The Athenian Option: Radical Reform for the House of Lords (2nd ed.). Imprint Academic.

- ^ "Let The People Wear Ermine If We Are to Abolish the House of Lords". Disclaimer. August 18, 2015. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016.

- ^ Ellersgaard, Christoph Houman; Larsen, Anton Grau; Mulvad, Andreas Møller. "Centrum-venstre skal tøjle eliten og give borgerne større indflydelse". Politiken (in Danish). Retrieved April 15, 2018.

- ^ "The campaign beat – Jean-Luc Mélenchon's call for a Sixth Republic". France 24. April 12, 2017. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "L'urgence démocratique – La 6e République". LAEC.fr (in French). Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ Grant, Adam (August 21, 2023). "Opinion | The Worst People Run for Office. It's Time for a Better Way". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

External links

- Equality by Lot blog — extensive news, discussions and general information on sortition

- Sortition as a sustainable protection against oligarchy (2011 lecture) by Étienne Chouard (video in French with English subtitles)

- Lists of writings on sortition

- Equality by Lot's list of books (from 425 BC - 2020)

- The Fetura or Sortition Option's list of writings (348 BC - 2002)

- List of Simon Threlkeld's articles (1997-2020) proposing randomly sampled juries decide laws and choose public officials

- List of sortition news from the Netherlands (2018-2022) (English-language)