Coconut crab: Difference between revisions

Stemonitis (talk | contribs) remove advice (WP:NOTHOW), and pet status - I can see no other reference to this, and I cannot find that citation |

Stemonitis (talk | contribs) further references; standardise spelling; etc. |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

| status_system = iucn2.3 |

| status_system = iucn2.3 |

||

| status_ref = <ref name="IUCN">{{IUCN2010 |assessors=L. G. Eldredge |version=2.3 |year=1996 |id=2811 |title=Birgus latro |downloaded=July 25, 2011}}</ref> |

| status_ref = <ref name="IUCN">{{IUCN2010 |assessors=L. G. Eldredge |version=2.3 |year=1996 |id=2811 |title=Birgus latro |downloaded=July 25, 2011}}</ref> |

||

| image = Birgus latro |

| image = Coconut Crab Birgus latro.jpg |

||

| regnum = [[Animal]]ia |

| regnum = [[Animal]]ia |

||

| phylum = [[Arthropod]]a |

| phylum = [[Arthropod]]a |

||

| Line 26: | Line 26: | ||

*''Birgus laticauda'' <small>Latreille, 1829</small> |

*''Birgus laticauda'' <small>Latreille, 1829</small> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''coconut crab''', '''''Birgus latro''''', is the largest land-living [[arthropod]] in the world, and is probably at the upper size limit of terrestrial animals with [[exoskeleton]]s in today's atmosphere. It is also known as the '''robber crab''' or '''palm thief''', because some coconut crabs are rumored to steal shiny items such as pots and silverware from houses and [[tent]]s. The species inhabits the coastal forest regions of many [[Indo-Pacific]] islands, although |

The '''coconut crab''', '''''Birgus latro''''', is the largest land-living [[arthropod]] in the world, and is probably at the upper size limit of terrestrial animals with [[exoskeleton]]s in today's atmosphere. It is also known as the '''robber crab''' or '''palm thief''', because some coconut crabs are rumored to steal shiny items such as pots and silverware from houses and [[tent]]s. The species inhabits the coastal forest regions of many [[Indo-Pacific]] islands, although localised extinction has occurred where the species lives close to humans. They are generally [[nocturnal]] and remain hidden during the day, emerging only on some nights to forage. It is a highly [[Cladistics#Terminology|apomorphic]] [[hermit crab]] and is known for its ability to crack [[coconut]]s with its strong [[claw|pincers]] to eat the contents. It is the [[monotypic|only species]] of the [[genus]] ''Birgus'', and is closely related to the terrestrial [[hermit crab]]s of the genus ''[[Coenobita]]''.<ref name="Hartnoll16">[[#refHartnoll|Hartnoll (1988)]], [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RR09AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA16 p. 16]</ref> |

||

==Description== |

==Description== |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

''Birgus latro'' is the largest land-living [[arthropod]] in the world, and is probably at the upper size limit of terrestrial animals with [[exoskeleton]]s in today's atmosphere.<ref name="isbn0-313-33922-8">{{cite book |author=R. Piper |title=Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals |publisher=Greenwood Press |location=Westport, CT |year=2007 |pages= |isbn=0-313-33922-8}}</ref> Reports about the size of ''Birgus latro'' vary, but most references give a body length of up to {{convert|40|cm|in|abbr=on}},<ref>{{cite book |author=Piotr Naskrecki |year=2005 |title=The Smaller Majority |publisher=Belknap Press of [[Harvard University Press]] |isbn=0-674-01915-6 |pages=38}}</ref> a weight of up to {{convert|4.1|kg|lb|abbr=on}}, and a leg span of more than {{convert|0.91|m|ft|abbr=on}},<ref name="IM0125">{{cite web |url=http://www.nationalgeographic.com/wildworld/profiles/terrestrial/im/im0125.html |work=Terrestrial Ecoregions |title=Maldives-Lakshadweep-Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests (IM0125) |accessdate=April 15, 2009 |publisher=[[National Geographic]] |year=2001 |author=[[World Wildlife Fund]]}}</ref> with males generally being larger than females.<ref name="Drew49">[[#refDrew|Drew ''et al.'' (2010)]], p. 49</ref> The [[carapace]] may reach a length of {{convert|78|mm|abbr=on}}, and a width of up to {{convert|200|mm|abbr=on}}.<ref name="Drew46">[[#refDrew|Drew ''et al.'' (2010)]], p. 46</ref> |

''Birgus latro'' is the largest land-living [[arthropod]] in the world, and is probably at the upper size limit of terrestrial animals with [[exoskeleton]]s in today's atmosphere.<ref name="isbn0-313-33922-8">{{cite book |author=R. Piper |title=Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals |publisher=Greenwood Press |location=Westport, CT |year=2007 |pages= |isbn=0-313-33922-8}}</ref> Reports about the size of ''Birgus latro'' vary, but most references give a body length of up to {{convert|40|cm|in|abbr=on}},<ref>{{cite book |author=Piotr Naskrecki |year=2005 |title=The Smaller Majority |publisher=Belknap Press of [[Harvard University Press]] |isbn=0-674-01915-6 |pages=38}}</ref> a weight of up to {{convert|4.1|kg|lb|abbr=on}}, and a leg span of more than {{convert|0.91|m|ft|abbr=on}},<ref name="IM0125">{{cite web |url=http://www.nationalgeographic.com/wildworld/profiles/terrestrial/im/im0125.html |work=Terrestrial Ecoregions |title=Maldives-Lakshadweep-Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests (IM0125) |accessdate=April 15, 2009 |publisher=[[National Geographic]] |year=2001 |author=[[World Wildlife Fund]]}}</ref> with males generally being larger than females.<ref name="Drew49">[[#refDrew|Drew ''et al.'' (2010)]], p. 49</ref> The [[carapace]] may reach a length of {{convert|78|mm|abbr=on}}, and a width of up to {{convert|200|mm|abbr=on}}.<ref name="Drew46">[[#refDrew|Drew ''et al.'' (2010)]], p. 46</ref> |

||

The body of the coconut crab is, like that of all [[Decapoda|decapods]], divided into a front section ([[cephalothorax]]), which has 10 [[arthropod leg|legs]], and an [[abdomen]]. The front-most pair of legs has large [[claw]]s used to open coconuts, and |

The body of the coconut crab is, like that of all [[Decapoda|decapods]], divided into a front section ([[cephalothorax]]), which has 10 [[arthropod leg|legs]], and an [[abdomen]]. The front-most pair of legs has large [[claw]]s (chelae), with the left being larger than the right.<ref name="Fletcher_644"/> They are used to open coconuts, and can lift objects up to {{convert|29|kg|lb}}. The next two pairs, as with other hermit crabs, are large, powerful walking legs with pointed tips, which allow coconut crabs to climb vertical or overhanging surfaces.<ref name="Greenaway_2003"/> The fourth pair of legs is smaller with [[tweezers|tweezer]]-like chelae at the end, allowing young coconut crabs to grip the inside of a shell or coconut husk to carry for protection; adults use this pair for walking and climbing. The last pair of legs is very small and is used by females to tend their eggs, and by the males in mating.<ref name="Fletcher_644"/> This last pair of legs is usually held inside the [[carapace]], in the cavity containing the breathing organs. There is some difference in colour between the animals found on different islands, ranging from orange-red to purplish blue;<ref name="ARKive"/> in most regions, blue is the predominant colour, but in some places, including the [[Seychelles]], most individuals are red.<ref name="Fletcher_644"/> |

||

Although ''Birgus latro'' is a [[apomorph|derived]] type of [[hermit crab]], only the juveniles use salvaged [[snail]] [[animal shell|shells]] to protect their soft abdomens, and adolescents sometimes use broken coconut shells to protect their abdomens. Unlike other hermit crabs, the adult coconut crabs do not carry shells but instead harden their abdominal [[terga]] by depositing [[chitin]] and [[chalk]]. Not being constrained by the physical confines of living in a shell allows this species to grow much larger than other hermit crabs in the family Coenobitidae.<ref name=Harms1932>{{cite journal |author=J. W. Harms |year=1932|title=''Birgus latro'' Linné als Landkrebs und seine Beziehungen zu den Coenobiten |journal=[[Zeitschrift für Wissenschaftliche Zoologie]] |volume=140 |pages=167–290 |language=German}}</ref> Like most [[crab|true crabs]], ''B. latro'' bends its [[Tail (anatomy)|tail]] underneath its body for protection. The hardened abdomen protects the coconut crab and reduces water loss on land, but has to be moulted |

Although ''Birgus latro'' is a [[apomorph|derived]] type of [[hermit crab]], only the juveniles use salvaged [[snail]] [[animal shell|shells]] to protect their soft abdomens, and adolescents sometimes use broken coconut shells to protect their abdomens. Unlike other hermit crabs, the adult coconut crabs do not carry shells but instead harden their abdominal [[terga]] by depositing [[chitin]] and [[chalk]]. Not being constrained by the physical confines of living in a shell allows this species to grow much larger than other hermit crabs in the family Coenobitidae.<ref name=Harms1932>{{cite journal |author=J. W. Harms |year=1932|title=''Birgus latro'' Linné als Landkrebs und seine Beziehungen zu den Coenobiten |journal=[[Zeitschrift für Wissenschaftliche Zoologie]] |volume=140 |pages=167–290 |language=German}}</ref> Like most [[crab|true crabs]], ''B. latro'' bends its [[Tail (anatomy)|tail]] underneath its body for protection.<ref name="Fletcher_644"/> The hardened abdomen protects the coconut crab and reduces water loss on land, but has to be moulted periodically. Adults moult annually, and dig a burrow up to {{convert|1|m|abbr=on}} long in which to hide while vulnerable.<ref name="Greenaway_2003"/> It remains in the burrow for 3–16 weeks, depending on the size of the animal.<ref name="Greenaway_2003"/> After [[Ecdysis|moulting]], it takes 1–3 weeks for the [[exoskeleton]] to harden, depending on the animal's size, during which time the animal's body is soft and vulnerable, and it stays hidden for protection.<ref>{{cite book |author=W. J. Fletcher, I. W. Brown, D. R. Fielder & A. Obed |year=1991 |title=Moulting and growth characteristics |pages=35–60}} In: [[#refBrownFielder|Brown & Fielder (1991)]]</ref> |

||

=== Respiration === |

=== Respiration === |

||

Except as [[larva]]e, coconut crabs cannot swim, and |

Except as [[larva]]e, coconut crabs cannot swim, and they will [[drowning|drown]] if left in water for more than an hour.<ref name="Fletcher_644">[[#Fletcher|Fletcher (1993)]], p. 644</ref> They use a special organ called a [[branchiostegal lung]] to breathe. This organ can be interpreted as a developmental stage between [[gill]]s and [[lung]]s, and is one of the most significant adaptations of the coconut crab to its [[habitat (ecology)|habitat]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=V. Storch & U. Welsch |year=1984 |title=Electron microscopic observations on the lungs of the coconut crab, ''Birgus latro'' (L.) (Crustacea, Decapoda) |journal=[[Zoologischer Anzeiger]] |volume=212 |pages=73–84}}</ref> The branchiostegal lung contains a [[biological tissue|tissue]] similar to that found in gills, but suited to the absorption of [[oxygen]] from air, rather than water. This organ is expanded laterally and is [[wikt:evaginate|evaginated]] to increase the surface area;<ref name="Greenaway_2003"/> located in the cephalothorax, it is optimally placed to reduce both the blood/gas diffusion distance and the return distance of oxygenated blood to the pericardium.<ref name=Farrelly2005/> Coconut crabs use their hindmost, smallest pair of legs to clean these breathing organs and to moisten them with water. The organs require water to properly function, and the coconut crab provides this by stroking its wet legs over the spongy tissues nearby. Coconut crabs may also drink water from small puddles by transferring it from their [[cheliped]]s to their [[maxilliped]]s.<ref name="Gross">{{cite journal |author=Warren J. Gross |year=1955 |title=Aspects of osmotic and ionic regulation in crabs showing the terrestrial habit |journal=[[American Naturalist]] |volume=89 |issue=847 |pages=205–222 |doi=10.1086/281884 |jstor=2458622}}</ref> |

||

In addition to the branchiostegal lung, the coconut crab has an additional rudimentary set of gills. Although these gills are comparable in number to aquatic species from the families [[Paguridae]] and the [[Diogenidae]], they are reduced in size and have comparatively less surface area.<ref name=Farrelly2005>{{cite journal |author=C. A. Farrelly & P. Greenaway |year=2004 |title=The morphology and vasculature of the respiratory organs of terrestrial hermit crabs (''Coenobita'' and ''Birgus''): gills, branchiostegal lungs and abdominal lungs |journal=[[Arthropod Structure and Development]] |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=63–87 |doi=10.1016/j.asd.2004.11.002}}</ref> While these gills were probably used to breathe under water in the evolutionary history of the species, they no longer provide sufficient oxygen, reflecting a decreased dependence on the gills for gas exchange and the development of other respiratory surfaces. |

In addition to the branchiostegal lung, the coconut crab has an additional rudimentary set of gills. Although these gills are comparable in number to aquatic species from the families [[Paguridae]] and the [[Diogenidae]], they are reduced in size and have comparatively less surface area.<ref name=Farrelly2005>{{cite journal |author=C. A. Farrelly & P. Greenaway |year=2004 |title=The morphology and vasculature of the respiratory organs of terrestrial hermit crabs (''Coenobita'' and ''Birgus''): gills, branchiostegal lungs and abdominal lungs |journal=[[Arthropod Structure and Development]] |volume=34 |issue=1 |pages=63–87 |doi=10.1016/j.asd.2004.11.002}}</ref> While these gills were probably used to breathe under water in the evolutionary history of the species, they no longer provide sufficient oxygen, reflecting a decreased dependence on the gills for gas exchange and the development of other respiratory surfaces. |

||

===Sense of smell=== |

===Sense of smell=== |

||

Another distinctive organ of the coconut crab is its "[[nose]]". The process of smelling works very differently depending on whether the smelled molecules are [[hydrophilic]] molecules in water or [[hydrophobic]] molecules in air. As most crabs live in the water, they have |

Another distinctive organ of the coconut crab is its "[[nose]]". The process of smelling works very differently depending on whether the smelled molecules are [[hydrophilic]] molecules in water or [[hydrophobic]] molecules in air. As most crabs live in the water, they have specialised organs called [[aesthetasc]]s on their [[Antenna (biology)|antennae]] to determine both the concentration and the direction of a smell. However, as coconut crabs live on the land, the aesthetascs on their antennae differ significantly from those of other crabs and look more like the smelling organs of [[insect]]s, called [[sensilia]]. While insects and the coconut crab originate from different evolutionary paths, the same need to detect smells in the air led to the development of remarkably similar organs, making it an example of [[convergent evolution]]. Coconut crabs also flick their antennae as insects do to enhance their reception. They have an excellent sense of smell and can detect interesting [[odor]]s over large distances. The smells of rotting meat, bananas, and coconuts, all potential food sources, catch their attention especially.<ref name=Stensmyr2005>{{cite journal |author=Marcus C. Stensmyr, Susanne Erland, Eric Hallberg, Rita Wallén, Peter Greenaway & Bill S. Hansson |year=2005 |title=Insect-like olfactory adaptations in the terrestrial giant robber crab |journal=[[Current Biology]] |volume=15 |issue=2 |pages=116–121 |doi=10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.069 |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]] |url=http://www.bees.unsw.edu.au/school/staff/greenaway/Stensmyr%20et%20al%202005%20Current%20Biology.pdf |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20090930162345/http://www.bees.unsw.edu.au/school/staff/greenaway/Stensmyr%20et%20al%202005%20Current%20Biology.pdf |archivedate=September 3, 2009 |pmid=15668166}}</ref> |

||

===Life cycle=== |

===Life cycle=== |

||

Coconut crabs mate frequently and quickly on dry land in the period from May to September, especially between early June and late August.<ref name=Sato2008>{{cite journal |author=Taku Sato & Kenzo Yoseda |year=2008 |title=Reproductive season and female maturity size of coconut crab ''Birgus latro'' on Hatoma Island, southern Japan |journal=[[Fisheries Science]] |volume=74 |issue=6 |pages=1277–1282 |doi=10.1111/j.1444-2906.2008.01652.x}}</ref> Male coconut crabs have [[spermatophore]]s and deposit a mass of spermatophores on the abdomen of the female;<ref>{{cite journal |author=C. C. Tudge |year=1991 |title=Spermatophore diversity within and among the hermit crab families, Coenobitidae, Diogenidae, and Paguridae (Paguroidae, Anomura, Decapoda) |journal=[[Biological Bulletin]] |volume=181 |issue=2 |pages=238–247 |doi=10.2307/1542095 |jstor=1542095 |publisher=Marine Biological Laboratory}}</ref> the abdomen opens at the base of the third pereiopods, and |

Coconut crabs mate frequently and quickly on dry land in the period from May to September, especially between early June and late August.<ref name=Sato2008>{{cite journal |author=Taku Sato & Kenzo Yoseda |year=2008 |title=Reproductive season and female maturity size of coconut crab ''Birgus latro'' on Hatoma Island, southern Japan |journal=[[Fisheries Science]] |volume=74 |issue=6 |pages=1277–1282 |doi=10.1111/j.1444-2906.2008.01652.x}}</ref> Male coconut crabs have [[spermatophore]]s and deposit a mass of spermatophores on the abdomen of the female;<ref>{{cite journal |author=C. C. Tudge |year=1991 |title=Spermatophore diversity within and among the hermit crab families, Coenobitidae, Diogenidae, and Paguridae (Paguroidae, Anomura, Decapoda) |journal=[[Biological Bulletin]] |volume=181 |issue=2 |pages=238–247 |doi=10.2307/1542095 |jstor=1542095 |publisher=Marine Biological Laboratory}}</ref> the abdomen opens at the base of the third pereiopods, and fertilisation is thought to occur on the external surface of the abdomen as the eggs pass through the spermatophore mass.<ref name="Schiller">{{cite book |author=C. Schiller, D. R. Fielder, I. W. Brown & A. Obed |year=1991 |pages=13–34 |title=Reproduction, early life-history and recruitment}} In: [[#refBrownFielder|Brown & Fielder (1991)]]</ref> The extrusion of eggs occurs on land in crevices or burrows near the shore.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Taku Sato & Kenzo Yoseda |year=2009 |title=Egg extrusion site of coconut crab ''Birgus latro'': direct observation of terrestrial egg extrusion |journal=Marine Biodiversity Records |publisher=[[Marine Biological Association]] |volume=2 |pages=e37 |url=http://www.mba.ac.uk/jmba/pdf/6370.pdf |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]] |doi=10.1017/S1755267209000426}}</ref> Shortly thereafter, the female lays her eggs and glues them to the underside of her abdomen, carrying the fertilised eggs underneath her body for a few months. At the time of hatching, the female coconut crab releases the eggs into the ocean.<ref name="Schiller"/> This usually takes place on rocky shores at dusk, especially when this coincides with high [[tide]].<ref name="Fletcher_656">[[#Fletcher|Fletcher (1993)]], p. 656</ref> The empty egg cases remain on the females body after the larvae have been released, and the female eats the egg cases within a few days.<ref name="Fletcher_656"/> |

||

The larvae float in the [[pelagic zone]] of the ocean with other [[plankton]] for 3–4 weeks,<ref name="Drew46"/> during which a large number of them are eaten by predators. The [[crustacean larvae|larvae]] pass through three to five ''zoea'' stages before moulting into the post-larval ''glaucothoe'' stage.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Fang-Lin Wang, Hwey-Lian Hsieh & Chang-Po Chen |year=2007 |title=Larval growth of the coconut crab ''Birgus latro'' with a discussion on the development mode of terrestrial hermit crabs |journal=[[Journal of Crustacean Biology]] |volume=27 |issue=4 |pages=616–625 |doi=10.1651/S-2797.1}}</ref> Upon reaching the glaucothoe stage of development, they settle to the bottom, find and wear a suitably sized gastropod shell, and migrate to the shoreline with other terrestrial hermit crabs.<ref name=Reese1968>{{cite journal |title=Studies on Decapod Larval Development |author=E. S. Reese & R. A. Kinzie |journal=[[Crustaceana]] |volume=Suppl. 2 |isbn=9789004004184 |year=1968 |pages=117–144 |chapter=The larval development of the coconut or robber crab ''Birgus latro'' (L.) in the laboratory (Anomura, Paguridae)}}</ref> At that time, they sometimes visit dry land. Afterwards, they leave the ocean permanently and lose the ability to breathe in water. As with all hermit crabs, they change their shells as they grow. Young coconut crabs that cannot find a seashell of the right size also often use broken coconut pieces. When they outgrow their shells, they develop a hardened abdomen. The coconut crab reaches [[sexual maturity]] around five years after hatching.<ref name="Schiller"/> They |

The larvae float in the [[pelagic zone]] of the ocean with other [[plankton]] for 3–4 weeks,<ref name="Drew46"/> during which a large number of them are eaten by predators. The [[crustacean larvae|larvae]] pass through three to five ''zoea'' stages before moulting into the post-larval ''glaucothoe'' stage.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Fang-Lin Wang, Hwey-Lian Hsieh & Chang-Po Chen |year=2007 |title=Larval growth of the coconut crab ''Birgus latro'' with a discussion on the development mode of terrestrial hermit crabs |journal=[[Journal of Crustacean Biology]] |volume=27 |issue=4 |pages=616–625 |doi=10.1651/S-2797.1}}</ref> Upon reaching the glaucothoe stage of development, they settle to the bottom, find and wear a suitably sized gastropod shell, and migrate to the shoreline with other terrestrial hermit crabs.<ref name=Reese1968>{{cite journal |title=Studies on Decapod Larval Development |author=E. S. Reese & R. A. Kinzie |journal=[[Crustaceana]] |volume=Suppl. 2 |isbn=9789004004184 |year=1968 |pages=117–144 |chapter=The larval development of the coconut or robber crab ''Birgus latro'' (L.) in the laboratory (Anomura, Paguridae)}}</ref> At that time, they sometimes visit dry land. Afterwards, they leave the ocean permanently and lose the ability to breathe in water. As with all hermit crabs, they change their shells as they grow. Young coconut crabs that cannot find a seashell of the right size also often use broken coconut pieces. When they outgrow their shells, they develop a hardened abdomen. The coconut crab reaches [[sexual maturity]] around five years after hatching.<ref name="Schiller"/> They reach their maximum size only after 40–60 years.<ref name="Greenaway_2003"/> |

||

==Distribution== |

==Distribution== |

||

Coconut crabs live in |

Coconut crabs live in the [[Indian Ocean]] and the central [[Pacific Ocean]], with a distribution that closely matches that of the [[Coconut|coconut palm]].<ref>[[#Fletcher|Fletcher (1993)]], p. 648</ref> The western limit of the range of ''B. latro'' is [[Zanzibar]], off the coast of [[Tanzania]].<ref name="Hartnoll16"/>, while the tropics [[Tropic of Cancer|of Cancer]] and [[Tropic of Capricorn|Capricorn]] mark the northern and southern limits, respectively, with very few population in the [[subtropics]], such as the [[Ryukyu Islands]].<ref name="Drew46"/> There is evidence that the coconut crab once lived on the mainlands of [[Australia]] and [[Madagascar]] and on the island of [[Mauritius]], but it no longer occurs in any of these places.<ref name="Drew46"/> |

||

[[Christmas Island]] in the Indian Ocean has the largest and best-preserved population in the world.{{citation needed|date=August 2011}} Other Indian Ocean populations exist on the [[Seychelles]], including [[Aldabra]] and [[Cosmoledo]],<ref>{{cite journal |author=J. Bowler |year=1999 |title=The robber crab ''Birgus latro'' on Aride Island, Seychelles |jouranl=[[Phelsuma]] |volume=7 |pages=56–58 |url=http://www.islandbiodiversity.com/Phelsuma%207-5.pdf |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]]}}</ref> but the coconut crab is extinct on the central islands.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Michael J. Samways, Peter M. Hitchins, Orty Bourquin & Jock Henwood |year=2010 |chapter=Restoration of a tropical island: Cousine Island, Seychelles |journal=[[Biodiversity and Conservation]] |volume=19 |issue=2 |pages=425–434 |title=Tropical Islands Biodiversity Crisis: The Indo-West Pacific |editor=David J. W. Lane |doi=10.1007/s10531-008-9524-z}}</ref> Coconut crabs occur on several of the [[Andaman Islands|Andaman]] and [[Nicobar Islands]] in the [[Bay of Bengal]]. They also occur on most of the islands, and the northern [[atoll]]s, of the [[Chagos Archipelago]].<ref>{{cite book |title=Afrotropical |volume=3 |series=Protected Areas of the World : a Review of National Systems |author=[[International Union for Conservation of Nature]] |year=1992 |isbn=9782831700922 |chapter=United Kingdom, British Indian Ocean Territory |pages=323–325 |url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=GAtfSkr1q6sC&pg=PT339}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | In the Pacific, |

||

| ⚫ | In the Pacific, the coconut crab's range became known only gradually. [[Charles Darwin]] believed it was only found on "a single coral island north of the [[Society Islands|Society group]]".<ref name=Streets1877/> The coconut crab is actually far more widespread, though it is not abundant on every Pacific island it inhabits.<ref name=Streets1877/> Large populations exist on the [[Cook Islands]], especially [[Pukapuka]], [[Suwarrow]], [[Mangaia]], [[Takutea]], [[Mauke]], [[Atiu]], and [[Palmerston Island]]. These are close to the eastern limit of its range, as are the [[Line Islands]] of [[Kiribati]], where the coconut crab is especially frequent on [[Teraina]] (Washington Island), with its abundant coconut palm forest.<ref name=Streets1877/> The [[Gambier Islands]] marks the species' eastern limit.<ref name="Hartnoll16"/> |

||

==Ecology== |

==Ecology== |

||

Coconut crabs are considered one of the most terrestrial [[Decapoda|decapods]],<ref>{{cite journal |author=Dorothy E. Bliss |year=1968 |title=Transition from water to land in decapod crustaceans |journal=[[American Zoologist]] |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=355–392 |jstor=3881398 |doi=10.1093/icb/8.3.355}}</ref> with most aspects of its life linked to a terrestrial existence. The coconut crab drowns in sea water in less than a day.<ref name="Gross"/> As they cannot swim as adults, coconut crabs over time must have |

Coconut crabs are considered one of the most terrestrial [[Decapoda|decapods]],<ref>{{cite journal |author=Dorothy E. Bliss |year=1968 |title=Transition from water to land in decapod crustaceans |journal=[[American Zoologist]] |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=355–392 |jstor=3881398 |doi=10.1093/icb/8.3.355}}</ref> with most aspects of its life linked to a terrestrial existence. The coconut crab drowns in sea water in less than a day.<ref name="Gross"/> As they cannot swim as adults, coconut crabs over time must have colonised the islands as larvae, which can swim, or on [[driftwood]] and other [[flotsam]]. |

||

===Diet=== |

===Diet=== |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Birgus latro.jpg|thumb|A coconut crab attacking a [[coconut]]]] |

||

The diet of coconut crabs consists primarily of fleshy [[fruit]]s (particularly ''[[Ochrosia ackeringae]]'', ''[[Arenga listeri]]'', ''[[Pandanus elatus]]'', ''[[Pandanus christmatensis|P. christmatensis]]''), nuts (coconuts ''[[Cocos nucifera]]'', ''[[Aleurites moluccana]]'') and seeds (''[[Annona reticulata]]''),<ref name=Wilde2004/> and on the [[pith]] of fallen trees.<ref name="Drew53"/> However, as they are [[ |

The diet of coconut crabs consists primarily of fleshy [[fruit]]s (particularly ''[[Ochrosia ackeringae]]'', ''[[Arenga listeri]]'', ''[[Pandanus elatus]]'', ''[[Pandanus christmatensis|P. christmatensis]]''), nuts (coconuts ''[[Cocos nucifera]]'', ''[[Aleurites moluccana]]'') and seeds (''[[Annona reticulata]]''),<ref name=Wilde2004/> and on the [[pith]] of fallen trees.<ref name="Drew53"/> However, as they are [[omnivore]]s, they will also consume other organic materials such as [[tortoise]] hatchlings and dead animals.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Peter Greenaway |year=2001 |title=Sodium and water balance in free-ranging robber crabs, ''Birgus latro'' (Anomura: Coenobitidae) |journal=[[Journal of Crustacean Biology]] |volume=21 |issue=2 |jstor=1549783 |pages=317–327 |doi=10.1651/0278-0372(2001)021[0317:SAWBIF]2.0.CO;2}}</ref><ref name="Greenaway_2003">{{cite journal |author=Peter Greenaway |year=2003 |title=Terrestrial adaptations in the Anomura (Crustacea: Decapoda) |journal=Memoirs of Museum Victoria |volume=60 |issue=1 |pages=13–26 |url=http://museumvictoria.com.au/pages/4017/60_1_greenaway.pdf |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]]}}</ref> They have also been observed to prey upon crabs like ''[[Gecarcoidea natalis]]'' and ''[[Discoplax hirtipes]]'', as well as scavenge on the carcasses of other coconut crabs.<ref name=Wilde2004>{{cite journal |author=Joanne E. Wilde, Stuart M. Linton & Peter Greenaway |year=2004 |title=Dietary assimilation and the digestive strategy of the omnivorous anomuran land crab ''Birgus latro'' (Coenobitidae) |journal=[[Journal of Comparative Physiology B]]: Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology |volume=174 |issue=4 |pages=299–308 |doi=10.1007/s00360-004-0415-7 |pmid=14760503}}</ref> During a tagging experiment, one coconut crab was observed catching and eating a [[Polynesian Rat]] (''Rattus exulans'').<ref>{{cite journal |author=Curt Kessler |year=2005 |title=Observation of a coconut crab, ''Birgus latro'' (Linnaeus, 1767) predation on a Polynesian rat, ''Rattus exulans'' (Peale, 1848) |journal=[[Crustaceana]] |volume=78 |issue=6 |pages=761–762 |doi=10.1163/156854005774353485}}</ref> Coconut crabs may be responsible for the disappearance of [[Amelia Earhart|Amelia Earhart's]] remains, consuming them after her death and hoarding her bones in their burrows.<ref>{{cite news |author=Rossella Lorenzi |url=http://news.discovery.com/history/amelia-earhart-resting-place.html |title=Earhart's Final Resting Place Believed Found |publisher=[[Discovery News]] |date=October 23, 2009 |accessdate=October 26, 2009}}</ref> Coconut crabs often try to steal food from each other and will pull their food into their burrows to be safe while eating. |

||

The coconut crab climbs trees to eat coconuts or fruit or to escape the heat. It is a common perception that the coconut crab cuts the coconuts from the tree to eat them on the ground (hence the German name ''{{lang|de|Palmendieb}}'', which literally means "palm thief", and the Dutch ''{{lang|nl|klapperdief}}''). The coconut crab can take a coconut from the ground and cut it to a husk nut, take it with its claw, climb up a tree |

The coconut crab climbs trees to eat coconuts or fruit or to escape the heat. It is a common perception that the coconut crab cuts the coconuts from the tree to eat them on the ground (hence the German name ''{{lang|de|Palmendieb}}'', which literally means "palm thief", and the Dutch ''{{lang|nl|klapperdief}}''). The coconut crab can take a coconut from the ground and cut it to a husk nut, take it with its claw, climb up a tree {{convert|10|m|abbr=on}} high and drop the husk nut, to access the content inside.<ref>{{cite web |author=Anonymous |year=undated |title=Coconut Crabs (''Birgus latro'' L.) |page=1–6 |url=http://www.botany.hawaii.edu/basch/uhnpscesu/pdfs/sam/AnonundatedaAS.pdf |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]] |accessdate=May 23, 2009 |publisher=[[University of Hawaii]]}}</ref> Coconut crabs cut holes into coconuts with their strong claws and eat the contents, although it can take several days before the coconut is opened.<ref name="Drew53">[[#refDrew|Drew ''et al.'' (2010)]], p. 53</ref> |

||

[[Thomas Hale Streets]] discussed the behaviour in 1877, doubting that the animal would climb trees to get at the nuts.<ref name=Streets1877>{{cite journal |author=Thomas H. Streets |year=1877 |title=Some account of the natural history of the Fanning group of islands |journal=[[American Naturalist]] |volume=11 |issue=2 |pages=65–72 |jstor=2448050 |doi=10.1086/271824}}</ref> In the 1980s, Holger Rumpf was able to confirm Streets's report, observing and studying how they open coconuts in the wild. The animal has developed a special technique to do so: if the coconut is still covered with [[husk]], it will use its claws to rip off strips, always starting from the side with the three [[germination]] pores, the group of three small circles found on the outside of the coconut. Once the pores are visible, the coconut crab will bang its pincers on one of them until they break. Afterwards, it will turn around and use the smaller pincers on its other legs to pull out the white flesh of the coconut. Using their strong claws, larger individuals can even break the hard coconut into smaller pieces for easier consumption. |

[[Thomas Hale Streets]] discussed the behaviour in 1877, doubting that the animal would climb trees to get at the nuts.<ref name=Streets1877>{{cite journal |author=Thomas H. Streets |year=1877 |title=Some account of the natural history of the Fanning group of islands |journal=[[American Naturalist]] |volume=11 |issue=2 |pages=65–72 |jstor=2448050 |doi=10.1086/271824}}</ref> In the 1980s, Holger Rumpf was able to confirm Streets's report, observing and studying how they open coconuts in the wild. The animal has developed a special technique to do so: if the coconut is still covered with [[husk]], it will use its claws to rip off strips, always starting from the side with the three [[germination]] pores, the group of three small circles found on the outside of the coconut. Once the pores are visible, the coconut crab will bang its pincers on one of them until they break. Afterwards, it will turn around and use the smaller pincers on its other legs to pull out the white flesh of the coconut. Using their strong claws, larger individuals can even break the hard coconut into smaller pieces for easier consumption. |

||

===Habitat=== |

===Habitat=== |

||

[[File:Birgus latro (Bora-Bora).jpg|thumb|Coconut crabs |

[[File:Birgus latro (Bora-Bora).jpg|thumb|Coconut crabs vary in size and colouring.]] |

||

Coconut crabs live alone in underground burrows and rock crevices, depending on the local terrain. They dig their own burrows in sand or loose soil. During the day, the animal stays hidden to reduce water loss from heat. The coconut crabs' burrows contain very fine yet strong fibres of the coconut husk which the animal uses as bedding.<ref name=Streets1877/> While resting in its burrow, the coconut crab closes the entrances with one of its claws to create the moist microclimate within the burrow necessary for its breathing organs. In areas with a large coconut crab population, some may also come out during the day, perhaps to gain an advantage in the search for food. Coconut crabs will also sometimes come out during the day if it is moist or raining, since these conditions allow them to breathe more easily. They live almost exclusively on land, returning to the sea only to release its eggs; on [[Christmas Island]], for instance, ''B. latro'' is abundant {{convert|6|km|mi}} from the sea.<ref name="Hartnoll18">[[#refHartnoll|Hartnoll (1988)]], [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RR09AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA18 p. 18]</ref> |

Coconut crabs live alone in underground burrows and rock crevices, depending on the local terrain. They dig their own burrows in sand or loose soil. During the day, the animal stays hidden to reduce water loss from heat. The coconut crabs' burrows contain very fine yet strong fibres of the coconut husk which the animal uses as bedding.<ref name=Streets1877/> While resting in its burrow, the coconut crab closes the entrances with one of its claws to create the moist microclimate within the burrow necessary for its breathing organs. In areas with a large coconut crab population, some may also come out during the day, perhaps to gain an advantage in the search for food. Coconut crabs will also sometimes come out during the day if it is moist or raining, since these conditions allow them to breathe more easily. They live almost exclusively on land, returning to the sea only to release its eggs; on [[Christmas Island]], for instance, ''B. latro'' is abundant {{convert|6|km|mi}} from the sea.<ref name="Hartnoll18">[[#refHartnoll|Hartnoll (1988)]], [http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RR09AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA18 p. 18]</ref> |

||

| Line 74: | Line 76: | ||

Should a coconut crab pinch a person, it will not only cause pain, but is unlikely to release its grip. [[Thomas Hale Streets]] reports the following trick, used by [[Micronesia]]ns of the [[Line Islands]], to get a coconut crab to loosen its grip:<ref name=Streets1877/> |

Should a coconut crab pinch a person, it will not only cause pain, but is unlikely to release its grip. [[Thomas Hale Streets]] reports the following trick, used by [[Micronesia]]ns of the [[Line Islands]], to get a coconut crab to loosen its grip:<ref name=Streets1877/> |

||

{{ |

{{cquote|It may be interesting to know that in such a dilemma a gentle titillation of the under soft parts of the body with any light material will cause the crab to loosen its hold.}} |

||

In the [[Cook Islands]], the coconut crab is known as ''{{lang|rar|unga}}'' or ''{{lang|rar|kaveu}}'', and in the [[Marianas]] it is called ''ayuyu'', and is sometimes associated with ''{{lang|ch|[[taotaomo'na]]}}'' because of the traditional belief that ancestral spirits can return in the form of animals such as the coconut crab.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.buzzle.com/articles/a-giant-spider-that-can-crack-a-coconut-no-its-a-crab.html |title=A giant spider that can crack a coconut? no, it's a crab! |accessdate=April 15, 2009 |author=Linda Orlando |publisher=Buzzle}}</ref> |

In the [[Cook Islands]], the coconut crab is known as ''{{lang|rar|unga}}'' or ''{{lang|rar|kaveu}}'', and in the [[Marianas]] it is called ''ayuyu'', and is sometimes associated with ''{{lang|ch|[[taotaomo'na]]}}'' because of the traditional belief that ancestral spirits can return in the form of animals such as the coconut crab.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.buzzle.com/articles/a-giant-spider-that-can-crack-a-coconut-no-its-a-crab.html |title=A giant spider that can crack a coconut? no, it's a crab! |accessdate=April 15, 2009 |author=Linda Orlando |publisher=Buzzle}}</ref> |

||

==Conservation== |

==Conservation== |

||

Coconut crab populations in several areas have declined or become extinct due to both habitat loss and human predation.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Steven S. Amesbury |year=1980 |title=Biological studies on the coconut crab (''Birgus latro'') in the Mariana Islands |journal=University of Guam Technical Report |volume=17 |pages=1–39 |url=http://www.guammarinelab.com/publications/uogmltechrep66.pdf |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]]}}</ref><ref |

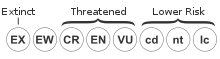

Coconut crab populations in several areas have declined or become extinct due to both habitat loss and human predation.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Steven S. Amesbury |year=1980 |title=Biological studies on the coconut crab (''Birgus latro'') in the Mariana Islands |journal=University of Guam Technical Report |volume=17 |pages=1–39 |url=http://www.guammarinelab.com/publications/uogmltechrep66.pdf |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]]}}</ref><ref>[[#Fletcher|Fletcher (1993)]], p. 643</ref> In 1981, it was listed on the [[IUCN Red List]] as a [[vulnerable species]], but a lack of biological data caused its assessment to be amended to ''[[Data Deficient]]'' in 1996.<ref name="Drew46"/> |

||

Conservation management strategies have been put in place in some regions, such as minimum legal size limit restrictions in [[Guam]] and [[Vanuatu]], and a ban on the capture of [[Oviparity|ovigerous]] females in Guam and the [[Federated States of Micronesia]].<ref>{{cite journal |year=2008 |title=Male maturity, number of sperm, and spermatophore size relationships in the coconut crab ''Birgus latro'' on Hatoma Island, southern Japan |journal=[[Journal of Crustacean Biology]] |volume=28 |issue=4 |pages=663–668 |doi=10.1651/07-2966.1 |author=Taku Sato, Kenzo Yoseda, Osamu Abe & Takuro Shibuno}}</ref> ''B. latro'' is protected in the [[British Indian Ocean Territory]] from being hunted or eaten, with fines of up to £1,500 (roughly $3,000 USD) per coconut crab consumed. |

Conservation management strategies have been put in place in some regions, such as minimum legal size limit restrictions in [[Guam]] and [[Vanuatu]], and a ban on the capture of [[Oviparity|ovigerous]] females in Guam and the [[Federated States of Micronesia]].<ref>{{cite journal |year=2008 |title=Male maturity, number of sperm, and spermatophore size relationships in the coconut crab ''Birgus latro'' on Hatoma Island, southern Japan |journal=[[Journal of Crustacean Biology]] |volume=28 |issue=4 |pages=663–668 |doi=10.1651/07-2966.1 |author=Taku Sato, Kenzo Yoseda, Osamu Abe & Takuro Shibuno}}</ref> ''B. latro'' is protected in the [[British Indian Ocean Territory]] from being hunted or eaten, with fines of up to £1,500 (roughly $3,000 USD) per coconut crab consumed. |

||

| Line 94: | Line 96: | ||

*{{cite book |editor=I. W. Brown & D. R. Fielder |year=1991 |title=The Coconut Crab: Aspects of the Biology and Ecology of ''Birgus latro'' in the Republic of Vanuatu |series=ACIAR Monograph |volume=8 |publisher=[[Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research]] |isbn=1-86320-054-1 |ref=refBrownFielder}} Available as [[Portable Document Format|PDF]]: [http://aciar.gov.au/system/files/node/10585/MN008%20part%201.pdf pp. i–x, 1–35], [http://aciar.gov.au/system/files/node/10585/MN008%20part%202.pdf pp. 36–82], [http://aciar.gov.au/system/files/node/10585/MN008%20part%203.pdf pp. 83–128] |

*{{cite book |editor=I. W. Brown & D. R. Fielder |year=1991 |title=The Coconut Crab: Aspects of the Biology and Ecology of ''Birgus latro'' in the Republic of Vanuatu |series=ACIAR Monograph |volume=8 |publisher=[[Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research]] |isbn=1-86320-054-1 |ref=refBrownFielder}} Available as [[Portable Document Format|PDF]]: [http://aciar.gov.au/system/files/node/10585/MN008%20part%201.pdf pp. i–x, 1–35], [http://aciar.gov.au/system/files/node/10585/MN008%20part%202.pdf pp. 36–82], [http://aciar.gov.au/system/files/node/10585/MN008%20part%203.pdf pp. 83–128] |

||

*{{cite journal |author=M. M. Drew, S. Harzsch, M. Stensmyr, S. Erland & B. S. Hansson |year=2010 |title=A review of the biology and ecology of the Robber Crab, ''Birgus latro'' (Linnaeus, 1767) (Anomura: Coenobitidae) |journal=[[Zoologischer Anzeiger]] |volume=249 |issue=1 |pages=45–67 |doi=10.1016/j.jcz.2010.03.001 |ref=refDrew}} |

*{{cite journal |author=M. M. Drew, S. Harzsch, M. Stensmyr, S. Erland & B. S. Hansson |year=2010 |title=A review of the biology and ecology of the Robber Crab, ''Birgus latro'' (Linnaeus, 1767) (Anomura: Coenobitidae) |journal=[[Zoologischer Anzeiger]] |volume=249 |issue=1 |pages=45–67 |doi=10.1016/j.jcz.2010.03.001 |ref=refDrew}} |

||

*{{cite book |author=Warwick J. Fletcher |chapter=Coconut crabs |editor=Andrew Wright & Lance Hill |year=1993 |title=Nearshore Marine Resources of the South Pacific: Information for Fisheries Development and Management |publisher=[[International Centre for Ocean Development]] |pages=643–681 |isbn=978-982-02-0082-1 |url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=JHlBw5rYuF0C&pg=PA643 |ref=Fletcher}} |

|||

*{{cite book |editor=Warren W. Burggren & Brian Robert McMahon |year=1988 |title=Biology of the Land Crabs |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=9780521306904 |author=Richard Hartnoll |chapter=Evolution, systematics, and geographical distribution |pages=6–54 |ref=refHartnoll |url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RR09AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA6}} |

*{{cite book |editor=Warren W. Burggren & Brian Robert McMahon |year=1988 |title=Biology of the Land Crabs |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=9780521306904 |author=Richard Hartnoll |chapter=Evolution, systematics, and geographical distribution |pages=6–54 |ref=refHartnoll |url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RR09AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA6}} |

||

*{{cite book |editor=Warren W. Burggren & Brian Robert McMahon |year=1988 |title=Biology of the Land Crabs |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=9780521306904 |author=Thomas G. Wolcott |chapter=Ecology |pages=55–96 |ref=refWolcott |url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RR09AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA55}} |

*{{cite book |editor=Warren W. Burggren & Brian Robert McMahon |year=1988 |title=Biology of the Land Crabs |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |isbn=9780521306904 |author=Thomas G. Wolcott |chapter=Ecology |pages=55–96 |ref=refWolcott |url=http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=RR09AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA55}} |

||

Revision as of 18:13, 10 August 2011

| Coconut crab | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Birgus Leach, 1816

|

| Species: | B. latro

|

| Binomial name | |

| Birgus latro | |

| |

| Coconut crabs live on most coasts in the blue area; red points are primary and yellow points secondary places of settlement | |

| Synonyms [3] | |

| |

The coconut crab, Birgus latro, is the largest land-living arthropod in the world, and is probably at the upper size limit of terrestrial animals with exoskeletons in today's atmosphere. It is also known as the robber crab or palm thief, because some coconut crabs are rumored to steal shiny items such as pots and silverware from houses and tents. The species inhabits the coastal forest regions of many Indo-Pacific islands, although localised extinction has occurred where the species lives close to humans. They are generally nocturnal and remain hidden during the day, emerging only on some nights to forage. It is a highly apomorphic hermit crab and is known for its ability to crack coconuts with its strong pincers to eat the contents. It is the only species of the genus Birgus, and is closely related to the terrestrial hermit crabs of the genus Coenobita.[4]

Description

Birgus latro is the largest land-living arthropod in the world, and is probably at the upper size limit of terrestrial animals with exoskeletons in today's atmosphere.[5] Reports about the size of Birgus latro vary, but most references give a body length of up to 40 cm (16 in),[6] a weight of up to 4.1 kg (9.0 lb), and a leg span of more than 0.91 m (3.0 ft),[7] with males generally being larger than females.[8] The carapace may reach a length of 78 mm (3.1 in), and a width of up to 200 mm (7.9 in).[9]

The body of the coconut crab is, like that of all decapods, divided into a front section (cephalothorax), which has 10 legs, and an abdomen. The front-most pair of legs has large claws (chelae), with the left being larger than the right.[10] They are used to open coconuts, and can lift objects up to 29 kilograms (64 lb). The next two pairs, as with other hermit crabs, are large, powerful walking legs with pointed tips, which allow coconut crabs to climb vertical or overhanging surfaces.[11] The fourth pair of legs is smaller with tweezer-like chelae at the end, allowing young coconut crabs to grip the inside of a shell or coconut husk to carry for protection; adults use this pair for walking and climbing. The last pair of legs is very small and is used by females to tend their eggs, and by the males in mating.[10] This last pair of legs is usually held inside the carapace, in the cavity containing the breathing organs. There is some difference in colour between the animals found on different islands, ranging from orange-red to purplish blue;[12] in most regions, blue is the predominant colour, but in some places, including the Seychelles, most individuals are red.[10]

Although Birgus latro is a derived type of hermit crab, only the juveniles use salvaged snail shells to protect their soft abdomens, and adolescents sometimes use broken coconut shells to protect their abdomens. Unlike other hermit crabs, the adult coconut crabs do not carry shells but instead harden their abdominal terga by depositing chitin and chalk. Not being constrained by the physical confines of living in a shell allows this species to grow much larger than other hermit crabs in the family Coenobitidae.[13] Like most true crabs, B. latro bends its tail underneath its body for protection.[10] The hardened abdomen protects the coconut crab and reduces water loss on land, but has to be moulted periodically. Adults moult annually, and dig a burrow up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) long in which to hide while vulnerable.[11] It remains in the burrow for 3–16 weeks, depending on the size of the animal.[11] After moulting, it takes 1–3 weeks for the exoskeleton to harden, depending on the animal's size, during which time the animal's body is soft and vulnerable, and it stays hidden for protection.[14]

Respiration

Except as larvae, coconut crabs cannot swim, and they will drown if left in water for more than an hour.[10] They use a special organ called a branchiostegal lung to breathe. This organ can be interpreted as a developmental stage between gills and lungs, and is one of the most significant adaptations of the coconut crab to its habitat.[15] The branchiostegal lung contains a tissue similar to that found in gills, but suited to the absorption of oxygen from air, rather than water. This organ is expanded laterally and is evaginated to increase the surface area;[11] located in the cephalothorax, it is optimally placed to reduce both the blood/gas diffusion distance and the return distance of oxygenated blood to the pericardium.[16] Coconut crabs use their hindmost, smallest pair of legs to clean these breathing organs and to moisten them with water. The organs require water to properly function, and the coconut crab provides this by stroking its wet legs over the spongy tissues nearby. Coconut crabs may also drink water from small puddles by transferring it from their chelipeds to their maxillipeds.[17]

In addition to the branchiostegal lung, the coconut crab has an additional rudimentary set of gills. Although these gills are comparable in number to aquatic species from the families Paguridae and the Diogenidae, they are reduced in size and have comparatively less surface area.[16] While these gills were probably used to breathe under water in the evolutionary history of the species, they no longer provide sufficient oxygen, reflecting a decreased dependence on the gills for gas exchange and the development of other respiratory surfaces.

Sense of smell

Another distinctive organ of the coconut crab is its "nose". The process of smelling works very differently depending on whether the smelled molecules are hydrophilic molecules in water or hydrophobic molecules in air. As most crabs live in the water, they have specialised organs called aesthetascs on their antennae to determine both the concentration and the direction of a smell. However, as coconut crabs live on the land, the aesthetascs on their antennae differ significantly from those of other crabs and look more like the smelling organs of insects, called sensilia. While insects and the coconut crab originate from different evolutionary paths, the same need to detect smells in the air led to the development of remarkably similar organs, making it an example of convergent evolution. Coconut crabs also flick their antennae as insects do to enhance their reception. They have an excellent sense of smell and can detect interesting odors over large distances. The smells of rotting meat, bananas, and coconuts, all potential food sources, catch their attention especially.[18]

Life cycle

Coconut crabs mate frequently and quickly on dry land in the period from May to September, especially between early June and late August.[19] Male coconut crabs have spermatophores and deposit a mass of spermatophores on the abdomen of the female;[20] the abdomen opens at the base of the third pereiopods, and fertilisation is thought to occur on the external surface of the abdomen as the eggs pass through the spermatophore mass.[21] The extrusion of eggs occurs on land in crevices or burrows near the shore.[22] Shortly thereafter, the female lays her eggs and glues them to the underside of her abdomen, carrying the fertilised eggs underneath her body for a few months. At the time of hatching, the female coconut crab releases the eggs into the ocean.[21] This usually takes place on rocky shores at dusk, especially when this coincides with high tide.[23] The empty egg cases remain on the females body after the larvae have been released, and the female eats the egg cases within a few days.[23]

The larvae float in the pelagic zone of the ocean with other plankton for 3–4 weeks,[9] during which a large number of them are eaten by predators. The larvae pass through three to five zoea stages before moulting into the post-larval glaucothoe stage.[24] Upon reaching the glaucothoe stage of development, they settle to the bottom, find and wear a suitably sized gastropod shell, and migrate to the shoreline with other terrestrial hermit crabs.[25] At that time, they sometimes visit dry land. Afterwards, they leave the ocean permanently and lose the ability to breathe in water. As with all hermit crabs, they change their shells as they grow. Young coconut crabs that cannot find a seashell of the right size also often use broken coconut pieces. When they outgrow their shells, they develop a hardened abdomen. The coconut crab reaches sexual maturity around five years after hatching.[21] They reach their maximum size only after 40–60 years.[11]

Distribution

Coconut crabs live in the Indian Ocean and the central Pacific Ocean, with a distribution that closely matches that of the coconut palm.[26] The western limit of the range of B. latro is Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanzania.[4], while the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn mark the northern and southern limits, respectively, with very few population in the subtropics, such as the Ryukyu Islands.[9] There is evidence that the coconut crab once lived on the mainlands of Australia and Madagascar and on the island of Mauritius, but it no longer occurs in any of these places.[9]

Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean has the largest and best-preserved population in the world.[citation needed] Other Indian Ocean populations exist on the Seychelles, including Aldabra and Cosmoledo,[27] but the coconut crab is extinct on the central islands.[28] Coconut crabs occur on several of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal. They also occur on most of the islands, and the northern atolls, of the Chagos Archipelago.[29]

In the Pacific, the coconut crab's range became known only gradually. Charles Darwin believed it was only found on "a single coral island north of the Society group".[30] The coconut crab is actually far more widespread, though it is not abundant on every Pacific island it inhabits.[30] Large populations exist on the Cook Islands, especially Pukapuka, Suwarrow, Mangaia, Takutea, Mauke, Atiu, and Palmerston Island. These are close to the eastern limit of its range, as are the Line Islands of Kiribati, where the coconut crab is especially frequent on Teraina (Washington Island), with its abundant coconut palm forest.[30] The Gambier Islands marks the species' eastern limit.[4]

Ecology

Coconut crabs are considered one of the most terrestrial decapods,[31] with most aspects of its life linked to a terrestrial existence. The coconut crab drowns in sea water in less than a day.[17] As they cannot swim as adults, coconut crabs over time must have colonised the islands as larvae, which can swim, or on driftwood and other flotsam.

Diet

The diet of coconut crabs consists primarily of fleshy fruits (particularly Ochrosia ackeringae, Arenga listeri, Pandanus elatus, P. christmatensis), nuts (coconuts Cocos nucifera, Aleurites moluccana) and seeds (Annona reticulata),[32] and on the pith of fallen trees.[33] However, as they are omnivores, they will also consume other organic materials such as tortoise hatchlings and dead animals.[34][11] They have also been observed to prey upon crabs like Gecarcoidea natalis and Discoplax hirtipes, as well as scavenge on the carcasses of other coconut crabs.[32] During a tagging experiment, one coconut crab was observed catching and eating a Polynesian Rat (Rattus exulans).[35] Coconut crabs may be responsible for the disappearance of Amelia Earhart's remains, consuming them after her death and hoarding her bones in their burrows.[36] Coconut crabs often try to steal food from each other and will pull their food into their burrows to be safe while eating.

The coconut crab climbs trees to eat coconuts or fruit or to escape the heat. It is a common perception that the coconut crab cuts the coconuts from the tree to eat them on the ground (hence the German name Palmendieb, which literally means "palm thief", and the Dutch klapperdief). The coconut crab can take a coconut from the ground and cut it to a husk nut, take it with its claw, climb up a tree 10 m (33 ft) high and drop the husk nut, to access the content inside.[37] Coconut crabs cut holes into coconuts with their strong claws and eat the contents, although it can take several days before the coconut is opened.[33]

Thomas Hale Streets discussed the behaviour in 1877, doubting that the animal would climb trees to get at the nuts.[30] In the 1980s, Holger Rumpf was able to confirm Streets's report, observing and studying how they open coconuts in the wild. The animal has developed a special technique to do so: if the coconut is still covered with husk, it will use its claws to rip off strips, always starting from the side with the three germination pores, the group of three small circles found on the outside of the coconut. Once the pores are visible, the coconut crab will bang its pincers on one of them until they break. Afterwards, it will turn around and use the smaller pincers on its other legs to pull out the white flesh of the coconut. Using their strong claws, larger individuals can even break the hard coconut into smaller pieces for easier consumption.

Habitat

Coconut crabs live alone in underground burrows and rock crevices, depending on the local terrain. They dig their own burrows in sand or loose soil. During the day, the animal stays hidden to reduce water loss from heat. The coconut crabs' burrows contain very fine yet strong fibres of the coconut husk which the animal uses as bedding.[30] While resting in its burrow, the coconut crab closes the entrances with one of its claws to create the moist microclimate within the burrow necessary for its breathing organs. In areas with a large coconut crab population, some may also come out during the day, perhaps to gain an advantage in the search for food. Coconut crabs will also sometimes come out during the day if it is moist or raining, since these conditions allow them to breathe more easily. They live almost exclusively on land, returning to the sea only to release its eggs; on Christmas Island, for instance, B. latro is abundant 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) from the sea.[38]

Relationship with people

Adult coconut crabs have no known predators other than other coconut crabs and humans. Its large size and the quality of its meat mean that the coconut crab is extensively hunted and is rare on all islands with a human population.[39] The coconut crab is eaten by Southeast Asians and Pacific Islanders and is considered a delicacy and an aphrodisiac, and intensive hunting has threatened the species' survival in some areas.[12] While the coconut crab itself is not innately poisonous, it may become so depending on its diet, and cases of coconut crab poisoning have occurred.[39][40]

Should a coconut crab pinch a person, it will not only cause pain, but is unlikely to release its grip. Thomas Hale Streets reports the following trick, used by Micronesians of the Line Islands, to get a coconut crab to loosen its grip:[30]

It may be interesting to know that in such a dilemma a gentle titillation of the under soft parts of the body with any light material will cause the crab to loosen its hold.

In the Cook Islands, the coconut crab is known as unga or kaveu, and in the Marianas it is called ayuyu, and is sometimes associated with taotaomo'na because of the traditional belief that ancestral spirits can return in the form of animals such as the coconut crab.[41]

Conservation

Coconut crab populations in several areas have declined or become extinct due to both habitat loss and human predation.[42][43] In 1981, it was listed on the IUCN Red List as a vulnerable species, but a lack of biological data caused its assessment to be amended to Data Deficient in 1996.[9]

Conservation management strategies have been put in place in some regions, such as minimum legal size limit restrictions in Guam and Vanuatu, and a ban on the capture of ovigerous females in Guam and the Federated States of Micronesia.[44] B. latro is protected in the British Indian Ocean Territory from being hunted or eaten, with fines of up to £1,500 (roughly $3,000 USD) per coconut crab consumed.

Taxonomic history

The coconut crab has been known to western scientists since the voyages of William Dampier around 1688.[45] Based on an account by Georg Eberhard Rumphius (1705), who had called the animal "Cancer cruentatus", Carl Linnaeus (1767) named the species Cancer latro, from the Latin latro, meaning "robber".[46] The genus Birgus was erected in 1816 by William Elford Leach, containing only Linnaeus' Cancer latro, which was thus renamed Birgus latro.[3]

References

- ^ Template:IUCN2010

- ^ Patsy McLaughlin (2010). P. McLaughlin (ed.). "Birgus latro (Linnaeus, 1767)". World Paguroidea database. World Register of Marine Species. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- ^ a b Patsy A. McLaughlin, Tomoyuki Komai, Rafael Lemaitre & Dwi Listyo Rahayu (2010). Martyn E. Y. Low and S. H. Tan (ed.). "Annotated checklist of anomuran decapod crustaceans of the world (exclusive of the Kiwaoidea and families Chirostylidae and Galatheidae of the Galatheoidea)" (PDF). Zootaxa. Suppl. 23: 5–107.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Hartnoll (1988), p. 16

- ^ R. Piper (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-33922-8.

- ^ Piotr Naskrecki (2005). The Smaller Majority. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-674-01915-6.

- ^ World Wildlife Fund (2001). "Maldives-Lakshadweep-Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests (IM0125)". Terrestrial Ecoregions. National Geographic. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ Drew et al. (2010), p. 49

- ^ a b c d e Drew et al. (2010), p. 46

- ^ a b c d e Fletcher (1993), p. 644

- ^ a b c d e f Peter Greenaway (2003). "Terrestrial adaptations in the Anomura (Crustacea: Decapoda)" (PDF). Memoirs of Museum Victoria. 60 (1): 13–26.

- ^ a b "Coconut crab (Birgus latro)". ARKive. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ J. W. Harms (1932). "Birgus latro Linné als Landkrebs und seine Beziehungen zu den Coenobiten". Zeitschrift für Wissenschaftliche Zoologie (in German). 140: 167–290.

- ^ W. J. Fletcher, I. W. Brown, D. R. Fielder & A. Obed (1991). Moulting and growth characteristics. pp. 35–60.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) In: Brown & Fielder (1991) - ^ V. Storch & U. Welsch (1984). "Electron microscopic observations on the lungs of the coconut crab, Birgus latro (L.) (Crustacea, Decapoda)". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 212: 73–84.

- ^ a b C. A. Farrelly & P. Greenaway (2004). "The morphology and vasculature of the respiratory organs of terrestrial hermit crabs (Coenobita and Birgus): gills, branchiostegal lungs and abdominal lungs". Arthropod Structure and Development. 34 (1): 63–87. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2004.11.002.

- ^ a b Warren J. Gross (1955). "Aspects of osmotic and ionic regulation in crabs showing the terrestrial habit". American Naturalist. 89 (847): 205–222. doi:10.1086/281884. JSTOR 2458622.

- ^ Marcus C. Stensmyr, Susanne Erland, Eric Hallberg, Rita Wallén, Peter Greenaway & Bill S. Hansson (2005). "Insect-like olfactory adaptations in the terrestrial giant robber crab" (PDF). Current Biology. 15 (2): 116–121. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.069. PMID 15668166. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2009.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; September 30, 2009 suggested (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taku Sato & Kenzo Yoseda (2008). "Reproductive season and female maturity size of coconut crab Birgus latro on Hatoma Island, southern Japan". Fisheries Science. 74 (6): 1277–1282. doi:10.1111/j.1444-2906.2008.01652.x.

- ^ C. C. Tudge (1991). "Spermatophore diversity within and among the hermit crab families, Coenobitidae, Diogenidae, and Paguridae (Paguroidae, Anomura, Decapoda)". Biological Bulletin. 181 (2). Marine Biological Laboratory: 238–247. doi:10.2307/1542095. JSTOR 1542095.

- ^ a b c C. Schiller, D. R. Fielder, I. W. Brown & A. Obed (1991). Reproduction, early life-history and recruitment. pp. 13–34.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) In: Brown & Fielder (1991) - ^ Taku Sato & Kenzo Yoseda (2009). "Egg extrusion site of coconut crab Birgus latro: direct observation of terrestrial egg extrusion" (PDF). Marine Biodiversity Records. 2. Marine Biological Association: e37. doi:10.1017/S1755267209000426.

- ^ a b Fletcher (1993), p. 656

- ^ Fang-Lin Wang, Hwey-Lian Hsieh & Chang-Po Chen (2007). "Larval growth of the coconut crab Birgus latro with a discussion on the development mode of terrestrial hermit crabs". Journal of Crustacean Biology. 27 (4): 616–625. doi:10.1651/S-2797.1.

- ^ E. S. Reese & R. A. Kinzie (1968). "Studies on Decapod Larval Development". Crustaceana. Suppl. 2: 117–144. ISBN 9789004004184.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ Fletcher (1993), p. 648

- ^ J. Bowler (1999). "The robber crab Birgus latro on Aride Island, Seychelles" (PDF). 7: 56–58.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|jouranl=ignored (help) - ^ Michael J. Samways, Peter M. Hitchins, Orty Bourquin & Jock Henwood (2010). David J. W. Lane (ed.). "Tropical Islands Biodiversity Crisis: The Indo-West Pacific". Biodiversity and Conservation. 19 (2): 425–434. doi:10.1007/s10531-008-9524-z.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ International Union for Conservation of Nature (1992). "United Kingdom, British Indian Ocean Territory". Afrotropical. Protected Areas of the World : a Review of National Systems. Vol. 3. pp. 323–325. ISBN 9782831700922.

- ^ a b c d e f Thomas H. Streets (1877). "Some account of the natural history of the Fanning group of islands". American Naturalist. 11 (2): 65–72. doi:10.1086/271824. JSTOR 2448050.

- ^ Dorothy E. Bliss (1968). "Transition from water to land in decapod crustaceans". American Zoologist. 8 (3): 355–392. doi:10.1093/icb/8.3.355. JSTOR 3881398.

- ^ a b Joanne E. Wilde, Stuart M. Linton & Peter Greenaway (2004). "Dietary assimilation and the digestive strategy of the omnivorous anomuran land crab Birgus latro (Coenobitidae)". Journal of Comparative Physiology B: Biochemical, Systemic, and Environmental Physiology. 174 (4): 299–308. doi:10.1007/s00360-004-0415-7. PMID 14760503.

- ^ a b Drew et al. (2010), p. 53

- ^ Peter Greenaway (2001). "Sodium and water balance in free-ranging robber crabs, Birgus latro (Anomura: Coenobitidae)". Journal of Crustacean Biology. 21 (2): 317–327. doi:10.1651/0278-0372(2001)021[0317:SAWBIF]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 1549783.

- ^ Curt Kessler (2005). "Observation of a coconut crab, Birgus latro (Linnaeus, 1767) predation on a Polynesian rat, Rattus exulans (Peale, 1848)". Crustaceana. 78 (6): 761–762. doi:10.1163/156854005774353485.

- ^ Rossella Lorenzi (October 23, 2009). "Earhart's Final Resting Place Believed Found". Discovery News. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ Anonymous (undated). "Coconut Crabs (Birgus latro L.)" (PDF). University of Hawaii. p. 1–6. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Hartnoll (1988), p. 18

- ^ a b Wolcott (1988), p. 91

- ^ S. S. Deshpande (2002). "Seafood toxins and poisoning". Handbook of Food Toxicology. Volume 119 of Food Science and Technology. CRC Press. pp. 687–754. ISBN 9780824743901.

- ^ Linda Orlando. "A giant spider that can crack a coconut? no, it's a crab!". Buzzle. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- ^ Steven S. Amesbury (1980). "Biological studies on the coconut crab (Birgus latro) in the Mariana Islands" (PDF). University of Guam Technical Report. 17: 1–39.

- ^ Fletcher (1993), p. 643

- ^ Taku Sato, Kenzo Yoseda, Osamu Abe & Takuro Shibuno (2008). "Male maturity, number of sperm, and spermatophore size relationships in the coconut crab Birgus latro on Hatoma Island, southern Japan". Journal of Crustacean Biology. 28 (4): 663–668. doi:10.1651/07-2966.1.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ I. W. Brown & D. R. Fielder (1991). Project overview and literature survey. pp. 1–11. In: Brown & Fielder (1991)

- ^ Carl Linnaeus (1767). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae (in Latin) (12th ed.).

Bibliography

- I. W. Brown & D. R. Fielder, ed. (1991). The Coconut Crab: Aspects of the Biology and Ecology of Birgus latro in the Republic of Vanuatu. ACIAR Monograph. Vol. 8. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. ISBN 1-86320-054-1. Available as PDF: pp. i–x, 1–35, pp. 36–82, pp. 83–128

- M. M. Drew, S. Harzsch, M. Stensmyr, S. Erland & B. S. Hansson (2010). "A review of the biology and ecology of the Robber Crab, Birgus latro (Linnaeus, 1767) (Anomura: Coenobitidae)". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 249 (1): 45–67. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2010.03.001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Warwick J. Fletcher (1993). "Coconut crabs". In Andrew Wright & Lance Hill (ed.). Nearshore Marine Resources of the South Pacific: Information for Fisheries Development and Management. International Centre for Ocean Development. pp. 643–681. ISBN 978-982-02-0082-1.

- Richard Hartnoll (1988). "Evolution, systematics, and geographical distribution". In Warren W. Burggren & Brian Robert McMahon (ed.). Biology of the Land Crabs. Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–54. ISBN 9780521306904.

- Thomas G. Wolcott (1988). "Ecology". In Warren W. Burggren & Brian Robert McMahon (ed.). Biology of the Land Crabs. Cambridge University Press. pp. 55–96. ISBN 9780521306904.

External links

Media related to Birgus latro at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Birgus latro at Wikimedia Commons

Template:Link GA

Template:Link GA

Template:Link GA

Template:Link FA

Template:Link FA