Astrocyte: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→Recent studies: format cites |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

==Recent studies== |

==Recent studies== |

||

A recent study, done in November 2010 and published March 2011, was done by a team of scientists from the University of Rochester and University of Colorado School of Medicine led by Professor Chris Proschel. They did an experiment to attempt to repair trauma to the Central Nervous System of an adult rat by replacing the glial cells. When the glial cells were injected into the injury of the adult rat’s spinal cord, astrocytes were generated by exposing human glial precursor cells to bone morphogenetic protein (Bone morphogenetic protein is important because it is considered to create tissue architecture throughout the body). So, with the bone protein and human glial cells combined, they promoted significant recovery of conscious foot placement, axonal growth, and obvious increases in neuronal survival in the spinal cord laminae. On the other hand, human glial precursor cells and astrocytes generated from these cells by being in contact with ciliary neurotrophic factors, failed to promote neuronal survival and support of axonal growth at the spot of the injury.<ref name="ref34">Davies SJA, Shih C-H |

A recent study, done in November 2010 and published March 2011, was done by a team of scientists from the University of Rochester and University of Colorado School of Medicine led by Professor Chris Proschel. They did an experiment to attempt to repair trauma to the Central Nervous System of an adult rat by replacing the glial cells. When the glial cells were injected into the injury of the adult rat’s spinal cord, astrocytes were generated by exposing human glial precursor cells to bone morphogenetic protein (Bone morphogenetic protein is important because it is considered to create tissue architecture throughout the body). So, with the bone protein and human glial cells combined, they promoted significant recovery of conscious foot placement, axonal growth, and obvious increases in neuronal survival in the spinal cord laminae. On the other hand, human glial precursor cells and astrocytes generated from these cells by being in contact with ciliary neurotrophic factors, failed to promote neuronal survival and support of axonal growth at the spot of the injury.<ref name="ref34">{{cite journal | author=Davies SJA |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0017328 | author-separator=, | author2=Shih C-H | author3=Noble M | author4=Mayer-Proschel M | author5=Davies JE | display-authors=5 | title=Transplantation of Specific Human Astrocytes Promotes Functional ''Recovery after'' spinal Cord Injury | year=2011 | editor1-last=Combs | editor1-first=Colin | last6=Proschel | first6=Christoph | journal=PLoS ONE | volume=6 | issue=3 | pages=e17328 | pmid=21407803 | pmc=3047562 }}</ref> |

||

One study done in Shanghai had two types of hippocampal neuronal cultures: In one culture, the neuron was grown from a layer of astrocytes and the other culture was not in contact with any astrocytes, but they were instead fed a Glial Conditioned Medium (GCM), which inhibits the rapid growth of cultured astrocytes in the brains of rats in most cases. |

One study done in Shanghai had two types of hippocampal neuronal cultures: In one culture, the neuron was grown from a layer of astrocytes and the other culture was not in contact with any astrocytes, but they were instead fed a Glial Conditioned Medium (GCM), which inhibits the rapid growth of cultured astrocytes in the brains of rats in most cases. |

||

In their results they were able to see that astrocytes had a direct role in LTP with the mixed culture (which is the culture that was grown from a layer of astrocytes) but not in GCM cultures.<ref name="ref36"> |

In their results they were able to see that astrocytes had a direct role in LTP with the mixed culture (which is the culture that was grown from a layer of astrocytes) but not in GCM cultures.<ref name="ref36">{{cite journal | doi = 10.1073/pnas.2431073100 | title = Contribution of astrocytes to hippocampal long-term potentiation through release of D-serine | year = 2003 | last1 = Yang | first1 = Y. | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences | volume = 100 | issue = 25 | pages = 15194 }}</ref> |

||

Recent studies have shown that astrocytes play an important function in the regulation of neural [[stem cell]]s. Research from the Schepens Eye Research Institute at Harvard shows the human brain to abound in neural stem cells, which are kept in a dormant state by chemical signals (ephrin-A2 and ephrin-A3) from the astrocytes. The astrocytes are able to activate the stem cells to transform into working neurons by dampening the release of [[ephrin-A2]] and [[ephrin-A3]].{{Citation needed|date=June 2008}} |

Recent studies have shown that astrocytes play an important function in the regulation of neural [[stem cell]]s. Research from the Schepens Eye Research Institute at Harvard shows the human brain to abound in neural stem cells, which are kept in a dormant state by chemical signals (ephrin-A2 and ephrin-A3) from the astrocytes. The astrocytes are able to activate the stem cells to transform into working neurons by dampening the release of [[ephrin-A2]] and [[ephrin-A3]].{{Citation needed|date=June 2008}} |

||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

In a study published in a 2011 issue of Nature Biotechnology<ref>http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/vaop/ncurrent/abs/nbt.1877.html</ref> and reported in lay science article,<ref>http://www.sciencedebate.com/science-blog/human-astrocytes-cultivated-stem-cells-lab-dish-u-wisconsin-researchers</ref> a group of researchers from the University of Wisconsin reports that it has been able to direct embryonic and induced human [[stem cells]] to become astrocytes. |

In a study published in a 2011 issue of Nature Biotechnology<ref>http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/vaop/ncurrent/abs/nbt.1877.html</ref> and reported in lay science article,<ref>http://www.sciencedebate.com/science-blog/human-astrocytes-cultivated-stem-cells-lab-dish-u-wisconsin-researchers</ref> a group of researchers from the University of Wisconsin reports that it has been able to direct embryonic and induced human [[stem cells]] to become astrocytes. |

||

A 2012 study<ref>{{cite journal |author=Han J, Kesner P, Metna-Laurent M, Duan T, Xu L, Georges F, Koehl M, Abrous DN, Mendizabal-Zubiaga J, Grandes P, Liu Q, Bai G, Wang Q, Xiong L, Ren Q, Marsicano G, Zhang X |title=Acute Cannabinoids Impair Working Memory through Astroglial CB1 Receptor Modulation of Hippocampal LTD |journal=Cell |volume=148 |issue=5 |pages=1039–50 |year=2012 | url=http://www.cell.com/retrieve/pii/S0092867412001420 }}</ref> of the effects of [[marijuana]] on short term memories found that [[THC]] activates [[Cannabinoid receptor 1|CB1]] receptors of astrocytes which cause receptors for [[AMPA]] to be removed from the membranes of associated neurons. |

A 2012 study<ref>{{cite journal |author=Han J, Kesner P, Metna-Laurent M, Duan T, Xu L, Georges F, Koehl M, Abrous DN, Mendizabal-Zubiaga J, Grandes P, Liu Q, Bai G, Wang Q, Xiong L, Ren Q, Marsicano G, Zhang X |title=Acute Cannabinoids Impair Working Memory through Astroglial CB1 Receptor Modulation of Hippocampal LTD |journal=Cell |volume=148 |issue=5 |pages=1039–50 |year=2012 | url=http://www.cell.com/retrieve/pii/S0092867412001420 |doi=10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.037 |pmid=22385967 }}</ref> of the effects of [[marijuana]] on short term memories found that [[THC]] activates [[Cannabinoid receptor 1|CB1]] receptors of astrocytes which cause receptors for [[AMPA]] to be removed from the membranes of associated neurons. |

||

==Calcium waves== |

==Calcium waves== |

||

Revision as of 13:34, 18 April 2012

- For the cell in the gastrointestinal tract, see Interstitial cell of Cajal.

| Astrocyte | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D001253 |

| NeuroLex ID | sao1394521419 |

| TH | H2.00.06.2.00002, H2.00.06.2.01008 |

| FMA | 54537 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

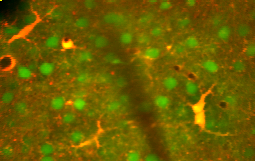

Astrocytes (etymology: astron gk. star, cyte gk. cell), also known collectively as astroglia, are characteristic star-shaped glial cells in the brain and spinal cord. They are the most abundant cell of the human brain. They perform many functions, including biochemical support of endothelial cells that form the blood–brain barrier, provision of nutrients to the nervous tissue, maintenance of extracellular ion balance, and a role in the repair and scarring process of the brain and spinal cord following traumatic injuries.

Research since the mid-1990s has shown that astrocytes propagate intercellular Ca2+ waves over long distances in response to stimulation, and, similar to neurons, release transmitters (called gliotransmitters) in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Data suggest that astrocytes also signal to neurons through Ca2+-dependent release of glutamate.[1] Such discoveries have made astrocytes an important area of research within the field of neuroscience.

Description

Astrocytes are a sub-type of glial cells in the central nervous system. They are also known as astrocytic glial cells. Star-shaped, their many processes envelope synapses made by neurons. Astrocytes are classically identified using histological analysis; many of these cells express the intermediate filament glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Several forms of astrocytes exist in the CNS including fibrous, protoplasmic, and radial. The fibrous glia are usually located within white matter, have relatively few organelles, and exhibit long unbranched cellular processes. This type often has "vascular feet" that physically connect the cells to the outside of capillary wall when they are in close proximity to them. The protoplasmic glia are the most prevalent and are found in grey matter tissue, possess a larger quantity of organelles, and exhibit short and highly branched tertiary processes. The radial glia are disposed in a plane perpendicular to axis of ventricles. One of their processes about the pia mater, while the other is deeply buried in gray matter. Radial glia are mostly present during development, playing a role in neuron migration. Mueller cells of retina and Bergmann glia cells of cerebellar cortex represent an exception, being present still during adulthood. When in proximity to the pia mater, all three forms of astrocytes send out processes to form the pia-glial membrane.

Functions

Previously in medical science, the neuronal network was considered the only important one, and astrocytes were looked upon as gap fillers. More recently, the function of astrocytes has been reconsidered,[2] and are now thought to play a number of active roles in the brain, including the secretion or absorption of neural transmitters and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier.[3] Following on this idea the concept of a "tripartite synapse" has been proposed, referring to the tight relationship occurring at synapses among a presynaptic element, a postsynaptic element and a glial element.[4]

- Structural: They are involved in the physical structuring of the brain. Astrocytes get their name because they are “star-shaped”. They are the most abundant glial cells in the brain that are closely associated with neuronal synapses. They regulate the transmission of electrical impulses within the brain.

- Metabolic support: They provide neurons with nutrients such as lactate.

- Blood–brain barrier: The astrocyte end-feet encircling endothelial cells were thought to aid in the maintenance of the blood–brain barrier, but recent research indicates that they do not play a substantial role; instead, it is the tight junctions and basal lamina of the cerebral endothelial cells that play the most substantial role in maintaining the barrier.[5] However, it has recently been shown that astrocyte activity is linked to blood flow in the brain, and that this is what is actually being measured in fMRI.[6]

- Transmitter uptake and release: Astrocytes express plasma membrane transporters such as glutamate transporters for several neurotransmitters, including glutamate, ATP, and GABA. More recently, astrocytes were shown to release glutamate or ATP in a vesicular, Ca2+-dependent manner.[7] (This has been disputed for hippocampal astrocytes.)[8]

- Regulation of ion concentration in the extracellular space: Astrocytes express potassium channels at a high density. When neurons are active, they release potassium, increasing the local extracellular concentration. Because astrocytes are highly permeable to potassium, they rapidly clear the excess accumulation in the extracellular space. If this function is interfered with, the extracellular concentration of potassium will rise, leading to neuronal depolarization by the Goldman equation. Abnormal accumulation of extracellular potassium is well known to result in epileptic neuronal activity.[citation needed]

- Modulation of synaptic transmission: In the supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus, rapid changes in astrocyte morphology have been shown to affect heterosynaptic transmission between neurons.[9] In the hippocampus, astrocytes suppress synaptic transmission by releasing ATP, which is hydrolyzed by ectonucliotidases to yield adenosine. Adenosine acts on neuronal adenosine receptors to inhibit synaptic transmission, thereby increasing the dynamic range available for LTP.[10]

- Vasomodulation: Astrocytes may serve as intermediaries in neuronal regulation of blood flow.[11]

- Promotion of the myelinating activity of oligodendrocytes: Electrical activity in neurons causes them to release ATP, which serves as an important stimulus for myelin to form. However, the ATP does not act directly on oligodendrocytes. Instead, it causes astrocytes to secrete cytokine leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), a regulatory protein that promotes the myelinating activity of oligodendrocytes. This suggest that astrocytes have an executive-coordinating role in the brain.[12]

- Nervous system repair: Upon injury to nerve cells within the central nervous system, astrocytes fill up the space to form a glial scar, repairing the area and replacing the CNS cells that cannot regenerate.[citation needed]

- Long-term potentiation: Scientists are arguing back and forth on if astrocytes integrate learning and memory in the hippocampus. We know that glial cells are included in neuronal synapses, but many of the LTP studies are preformed on slices, so that is where scientists are disagreeing on whether or not astrocytes have a direct role of modulating synaptic plasticity.

Recent studies

A recent study, done in November 2010 and published March 2011, was done by a team of scientists from the University of Rochester and University of Colorado School of Medicine led by Professor Chris Proschel. They did an experiment to attempt to repair trauma to the Central Nervous System of an adult rat by replacing the glial cells. When the glial cells were injected into the injury of the adult rat’s spinal cord, astrocytes were generated by exposing human glial precursor cells to bone morphogenetic protein (Bone morphogenetic protein is important because it is considered to create tissue architecture throughout the body). So, with the bone protein and human glial cells combined, they promoted significant recovery of conscious foot placement, axonal growth, and obvious increases in neuronal survival in the spinal cord laminae. On the other hand, human glial precursor cells and astrocytes generated from these cells by being in contact with ciliary neurotrophic factors, failed to promote neuronal survival and support of axonal growth at the spot of the injury.[13]

One study done in Shanghai had two types of hippocampal neuronal cultures: In one culture, the neuron was grown from a layer of astrocytes and the other culture was not in contact with any astrocytes, but they were instead fed a Glial Conditioned Medium (GCM), which inhibits the rapid growth of cultured astrocytes in the brains of rats in most cases. In their results they were able to see that astrocytes had a direct role in LTP with the mixed culture (which is the culture that was grown from a layer of astrocytes) but not in GCM cultures.[14]

Recent studies have shown that astrocytes play an important function in the regulation of neural stem cells. Research from the Schepens Eye Research Institute at Harvard shows the human brain to abound in neural stem cells, which are kept in a dormant state by chemical signals (ephrin-A2 and ephrin-A3) from the astrocytes. The astrocytes are able to activate the stem cells to transform into working neurons by dampening the release of ephrin-A2 and ephrin-A3.[citation needed]

Furthermore, studies are underway to determine whether astroglia play an instrumental role in depression, based on the link between diabetes and depression. Altered CNS glucose metabolism is seen in both these conditions, and the astroglial cells are the only cells with insulin receptors in the brain.

In a study published in a 2011 issue of Nature Biotechnology[15] and reported in lay science article,[16] a group of researchers from the University of Wisconsin reports that it has been able to direct embryonic and induced human stem cells to become astrocytes.

A 2012 study[17] of the effects of marijuana on short term memories found that THC activates CB1 receptors of astrocytes which cause receptors for AMPA to be removed from the membranes of associated neurons.

Calcium waves

Astrocytes are linked by gap junctions, creating an electrically coupled (functional) syncytium.[18]

An increase in intracellular calcium concentration can propagate outwards through this functional syncytium. Mechanisms of calcium wave propagation include diffusion of calcium ions and IP3 through gap junctions and extracellular ATP signalling.[19] Calcium elevations are the primary known axis of activation in astrocytes, and are necessary and sufficient for some types of astrocytic glutamate release.[20]

Development

Astrocytes are macroglial cells in the central nervous system. Astrocytes are derived from heterogeneous populations of progenitor cells in the neuroepithelium of the developing central nervous system. Recent works, summarized in a review by Rowitch and Kriegstein[21], indicate that there is remarkable similarity between the well known genetic mechanisms that specify the lineage of diverse neuron subtypes and that of macroglial cells. Just as with neuronal cell specification, canonical signaling factors like Sonic hedgehog (SHH), Fibroblast growth factor (FGFs), WNTs and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), provide positional information to developing macroglial cells through morphogen gradients along the dorsal–ventral, anterior–posterior and medial–lateral axes. The resultant patterning along the neuraxis leads to segmentation of the neuroepithelium into progenitor domains (p0, p1 p2, p3 and pMN) for distinct neuron types in the developing spinal cord. On the basis of several studies it is now believed that that this model also applies to macroglial cell specification. Studies carried out by Hochstim and colleagues have demonstrated that three distinct populations of astrocytes arise from the p1, p2 and p3 domains[22]. These subtypes of astrocytes can be identified on the basis of their expression of different transcription factors (PAX6, NKX6.1) and cell surface markers (reelin and SLIT1). The three populations of astrocyte subtypes which have been identified are 1) dorsally located VA1 astrocytes, derived from p1 domain, express PAX6 and reelin 2) ventrally located VA3 astrocytes, derived from p3, express NKX6.1 and SLIT1 and 3) and intermediate white-matter located VA2 astrocyte, derived from the p2 domain, which express PAX6, NKX6.1, reelin and SLIT1[23]. After astrocyte specification has occurred in the developing CNS, it is believed that astrocyte precursors migrate to their final positions within the nervous system before the process of terminal differentiation occurs.

Classification

There are several different ways to classify astrocytes.

Lineage and antigenic phenotype

These have been established by classic work by Raff et al. in early 1980s on Rat optic nerves.

- Type 1: Antigenically Ran2+, GFAP+, FGFR3+, A2B5-, thus resembling the "type 1 astrocyte" of the postnatal day 7 rat optic nerve. These can arise from the tripotential glial restricted precursor cells (GRP), but not from the bipotential O2A/OPC (oligodendrocyte, type 2 astrocyte precursor, also called Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell) cells.

- Type 2: Antigenically A2B5+, GFAP+, FGFR3-, Ran 2-. These cells can develop in vitro from the either tripotential GRP (probably via O2A stage) or from bipotential O2A cells (which some people[who?] think may in turn have been derived from the GRP) or in vivo when these progenitor cells are transplanted into lesion sites (but probably not in normal development, at least not in the rat optic nerve). Type-2 astrocytes are the major astrocytic component in postnatal optic nerve cultures that are generated by O2A cells grown in the presence of fetal calf serum but are not thought to exist in vivo (Fulton et al., 1992).

Anatomical classification

- Protoplasmic: found in grey matter and have many branching processes whose end-feet envelop synapses. Some protoplasmic astrocytes are generated by multipotent subventricular zone progenitor cells.[24][25]

- Gömöri-positive astrocytes. These are a subset of protoplasmic astrocytes that contain numerous cytoplasmic inclusions, or granules, that stain positively with Gömöri's chrome-alum hematoxylin stain. It is now known that these granules are formed from the remnants of degenerating mitochondria engulfed within lysosomes,[26] Some type of oxidative stress appears to be responsible for the mitochondrial damage within these specialized astrocytes. Gömöri-positive astrocytes are much more abundant within the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus and in the hippocampus than in other brain regions. They may have a role in regulating the response of the hypothalamus to glucose.[27][28]

- Fibrous: found in white matter and have long thin unbranched processes whose end-feet envelop nodes of Ranvier.[29] Some fibrous astrocytes are generated by radial glia.[30][31][32][33][34]

Transporter/receptor classification

- GluT type: express glutamate transporters (EAAT1/SLC1A3 and EAAT2/SLC1A2) and respond to synaptic release of glutamate by transporter currents

- GluR type: express glutamate receptors (mostly mGluR and AMPA type) and respond to synaptic release of glutamate by channel-mediated currents and IP3-dependent Ca2+ transients

Bergmann glia

Bergmann glia, a type of glia[35][36] also known as radial epithelial cells (as named by Camillo Golgi) or Golgi epithelial cells (GCEs; not to be mixed up with Golgi cells), are astrocytes in the cerebellum that have their cell bodies in the Purkinje cell layer and processes that extend into the molecular layer, terminating with bulbous endfeet at the pial surface. Bergmann glia express high densities of glutamate transporters that limit diffusion of the neurotransmitter glutamate during its release from synaptic terminals. Besides their role in early development of the cerebellum, Bergmann glia are also required for the pruning or addition of synapses.[citation needed]

Pathology

Astrocytomas are primary intracranial tumors derived from astrocytes cells of the brain. It is also possible that glial progenitors or neural stem cells give rise to astrocytomas.

Astrocytomas are brain tumors that develop from astrocytes. They may occur in many parts of the brain and sometimes in the spinal cord. They can occur at any age but they primarily occur in males. Astrocytomas are divided into two categories: Low grade (I and II) and High Grade (III and IV). Low grade tumors are more common in children and high grade tumors are more common in adults.[37]

Pilocytic Astrocytoma are Grade I tumors. They are considered benign and slow growing tumors. Pilocytic Astrocytomas frequently have cystic portions filled with fluid and a nodule, which is the solid portion. Most are located in the cerebellum. Therefore, most symptoms are related to balance or coordination difficulties.[37] They also occur more frequently in children and teens.[38]

Grade II Tumors grow relatively slow but invade surrounding healthy tissue. Usually considered benign but can grow into malignant tumors. Other names that are used are Fibrillary or Protoplasmic astrocytomas. They are prevalent in younger people who are often present with seizures.[38]

Anaplastic astrocytoma is classified as grade III and are malignant tumors. They grow more rapidly than lower grade tumors and tend to invade nearby healthy tissue. Anaplastic astrocytomas recur more frequently than lower grade tumors because of their tendency to spread into surrounding tissue makes them difficulty to completely remove surgically.[37]

Glioblastoma Multiforme is also a malignant tumor and classified as a grade IV. Glioblastomas can contain more than one cell type (i.e., astrocytes, oligondroctyes). Also, while one cell type may die off in response to a particular treatment, the other cell types may continue to multiply. Glioblastomas are the most invasive type of glial tumors. Grows rapidly and spreads to nearby tissue. Approximately 50% of astrocytomas are glioblastomas and are very difficult to treat.[37]

Tripartite synapse

Within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, activated astrocytes have the ability to respond to almost all neurotransmitters (Haydon, 2001) and, upon activation, release a multitude of neuroactive molecules such as glutamate, ATP, nitric oxide (NO), prostaglandins (PG), and D-serine, which in turn influences neuronal excitability. The close association between astrocytes and presynaptic and postsynaptic terminals as well as their ability to integrate synaptic activity and release neuromodulators has been termed the “tripartite synapse” (Araque et al., 1999). Synaptic modulation by astrocytes takes place because of this 3-part association.

Astrocytes in chronic pain sensitization

Under normal conditions, pain conduction begins with some noxious signal followed by an action potential carried by nociceptive (pain sensing) afferent neurons, which elicit excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSP) in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. That message is then relayed to the cerebral cortex, where we translate those EPSPs into “pain.” Since the discovery of astrocytic influence, our understanding of the conduction of pain has been dramatically complicated. Pain processing is no longer seen as a repetitive relay of signals from body to brain, but as a complex system that can be up- and down-regulated by a number of different factors. One factor at the forefront of recent research is in the pain-potentiating synapse located in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and the role of astrocytes in encapsulating these synapses. Garrison and co-workers (Garrison, 1991)[full citation needed] were the first to suggest association when they found a correlation between astrocyte hypertrophy in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and hypersensitivity to pain after peripheral nerve injury, typically considered an indicator of glial activation after injury. Astrocytes detect neuronal activity and can release chemical transmitters, which in turn control synaptic activity (Volters and Meldolesi, 2005; Haydon, 2001; Fellin, et al., 2006). In the past, hyperalgesia was thought to be modulated by the release of substance P and excitatory amino acids (EAA), such as glutamate, from the presynaptic afferent nerve terminals in the spinal cord dorsal horn. Subsequent activation of AMPA (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole proprionic acid), NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) and kainate subtypes of ionotropic glutamate receptors follows. It is the activation of these receptors that potentiates the pain signal up the spinal cord. This idea, although true, is an oversimplification of pain transduction. A litany of other neurotransmitter and neuromodulators, such as calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), somatostatin, vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), galanin, and vasopressin are all synthesized and released in response to noxious stimuli. In addition to each of these regulatory factors, several other interactions between pain-transmitting neurons and other neurons in the dorsal horn have added impact on pain pathways.

Two states of persistent pain

After persistent peripheral tissue damage there is a release of several factors from the injured tissue as well as in the spinal dorsal horn. These factors increase the responsiveness of the dorsal horn pain-projection neurons to ensuing stimuli, termed “spinal sensitization,” thus amplifying the pain impulse to the brain. Release of glutamate, substance P, and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) mediates NMDAR activation (originally silent because it is plugged by Mg2+), thus aiding in depolarization of the postsynaptic pain-transmitting neurons (PTN). In addition, activation of IP3 signaling and MAPKs (mitogen-activated protein kinases) such as ERK and JNK, bring about an increase in the synthesis of inflammatory factors that alter glutamate transporter function. ERK also further activates AMPARs and NMDARs in neurons. Nociception is further sensitized by the association of ATP and substance P with their respective receptors, [[P2X3]], and neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R), as well as activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors and release of BDNF. Persistent presence of glutamate in the synapse eventually results in dysregulation of GLT1 and GLAST, crucial transporters of glutamate into astrocytes. Ongoing excitation can also induce ERK and JNK activation, resulting in release of several inflammatory factors.

As noxious pain is sustained, spinal sensitization creates transcriptional changes in the neurons of the dorsal horn that lead to altered function for extended periods. Mobilization of Ca2+ from internal stores results from persistent synaptic activity and leads to the release of glutamate, ATP, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-6, nitric oxide (NO), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). Activated astrocytes are also a source of matrix metalloproteinase 2 (MMP2), which induces pro-IL-1β cleavage and sustains astrocyte activation. In this chronic signaling pathway, p38 is activated as a result of IL-1β signaling, and there is a presence of chemokines that trigger their receptors to become active. In response to nerve damage, heat shock proteins (HSP) are released and can bind to their respective TLRs, leading to further activation.

See also

References

- ^ Fiacco TA, Agulhon C, McCarthy KD (2008). "Sorting out Astrocyte Physiology from Pharmacology". Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 49 (1): 151–74. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145602. PMID 18834310.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Brain From Top To Bottom". Thebrain.mcgill.ca. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- ^ Kolb & Whishaw: Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology, 2008

- ^ Araque A, Parpura V, Sanzgiri RP, Haydon PG (1999). "Tripartite synapses: glia, the unacknowledged partner". Trends in Neuroscience. 22 (5): 208–215. doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01349-6. PMID 10322493.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ {{Kimelberg HK, Jalonen T, Walz W. Regulation of the brain microenvironment: transmitters and ions. In: Murphy S, editor. Astrocytes: pharmacology and function. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1993. p. 193–222.|date=January 2008}}

- ^ Swaminathan N (2008). "Brain-scan mystery solved". Scientific American Mind. Oct–Nov: 7.

- ^ Santello M, Volterra A (2008). "Synaptic modulation by astrocytes via Ca(2+)-dependent glutamate release". Neuroscience. Mar. 158 (1): 253–9. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.039. PMID 18455880.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|unused_data=ignored (help) - ^ Agulhon C, Fiacco T, McCarthy K (2010). "Hippocampal short- and long-term plasticity are not modulated by astrocyte Ca2+ signaling". Science. 327 (5970): 1250–1257. doi:10.1126/science.1184821. PMID 20203048.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Piet R, Vargová L, Syková E, Poulain D, Oliet S (2004). "Physiological contribution of the astrocytic environment of neurons to intersynaptic crosstalk". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101 (7): 2151–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308408100. PMC 357067. PMID 14766975.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pascual O, Casper KB, Kubera C, Zhang J, Revilla-Sanchez R, Sul JY, Takano H, Moss SJ, McCarthy K, Haydon PG (2005). "Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks". Science. 310 (5745): 113–6. doi:10.1126/science.1116916. PMID 16210541.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Parri R, Crunelli V (2003). "An astrocyte bridge from synapse to blood flow". Nat Neurosci. 6 (1): 5–6. doi:10.1038/nn0103-5. PMID 12494240.

- ^ Ishibashi T, Dakin K, Stevens B, Lee P, Kozlov S, Stewart C, Fields R (2006). "Astrocytes Promote Myelination in Response to Electrical Impulses". Neuron. 49 (6): 823–32. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.006. PMC 1474838. PMID 16543131.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davies SJA; Shih C-H; Noble M; Mayer-Proschel M; Davies JE; et al. (2011). Combs, Colin (ed.). "Transplantation of Specific Human Astrocytes Promotes Functional Recovery after spinal Cord Injury". PLoS ONE. 6 (3): e17328. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017328. PMC 3047562. PMID 21407803.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Yang, Y. (2003). "Contribution of astrocytes to hippocampal long-term potentiation through release of D-serine". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (25): 15194. doi:10.1073/pnas.2431073100.

- ^ http://www.nature.com/nbt/journal/vaop/ncurrent/abs/nbt.1877.html

- ^ http://www.sciencedebate.com/science-blog/human-astrocytes-cultivated-stem-cells-lab-dish-u-wisconsin-researchers

- ^ Han J, Kesner P, Metna-Laurent M, Duan T, Xu L, Georges F, Koehl M, Abrous DN, Mendizabal-Zubiaga J, Grandes P, Liu Q, Bai G, Wang Q, Xiong L, Ren Q, Marsicano G, Zhang X (2012). "Acute Cannabinoids Impair Working Memory through Astroglial CB1 Receptor Modulation of Hippocampal LTD". Cell. 148 (5): 1039–50. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.037. PMID 22385967.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bennett M, Contreras J, Bukauskas F, Sáez J (2003). "New roles for astrocytes: gap junction hemichannels have something to communicate". Trends Neurosci. 26 (11): 610–7. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2003.09.008. PMID 14585601.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Newman, EA.(2001)"Propagation of intercellular calcium waves in retinal astrocytes and Müller cells."J Neurosci. 21(7):2215-23

- ^ Parpura V, Haydon P (2000). "Physiological astrocytic calcium levels stimulate glutamate release to modulate adjacent neurons". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 97 (15): 8629–34. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.15.8629. PMC 26999. PMID 10900020.

- ^ David H. Rowitch & Arnold R. Kriegstein, (2010) Developmental genetics of vertebrate glial–cell specification Nature 468, 214–222 doi:10.1038/nature09611

- ^ Muroyama, Y., Fujiwara, Y., Orkin, S. H. & Rowitch, D. H. (2005) Specification of astrocytes by bHLH protein SCL in a restricted region of the neural tube. Nature 438, 360–363

- ^ Hochstim, C., Deneen, B., Lukaszewicz, A., Zhou, Q. & Anderson, D. J. (2008) Identification of positionally distinct astrocyte subtypes whose identities are specified by a homeodomain code. Cell 133,510–522

- ^ Levison SW, Goldman JE (1993). "Both oligodendrocytes and astrocytes develop from progenitors in the subventricular zone of postnatal rat forebrain". Neuron. 10 (2): 201–12. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(93)90311-E. PMID 8439409.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zerlin M, Levison SW, Goldman JE (1995). "Early patterns of migration, morphogenesis, and intermediate filament expression of subventricular zone cells in the postnatal rat forebrain". J. Neurosci. 15 (11): 7238–49. PMID 7472478.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brawer JR; Stein, Robert; Small, Lorne; Ciss�, Soriba; Schipper, Hyman M. (1994). "Composition of Gomori-positive inclusions in astrocytes of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus". Anatomical Record. 240 (3): 407–415. doi:10.1002/ar.1092400313. PMID 7825737.

{{cite journal}}: replacement character in|last4=at position 5 (help) - ^ Young JK, McKenzie JC (2004) "GLUT2 immunoreactivity in Gömöri-positive astrocytes of the hypothalamus."J. Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 52: 1519-1524 PMID

- ^ Marty N (2005). "Regulation of glucagon secretion by glucose transporter type 2 (glut2) and astrocyte-dependent glucose sensors". J. Clinical Investigation. 115: 3545.

- ^ Template:MUNAnatomy

- ^ Choi BH, Lapham LW (1978). "Radial glia in the human fetal cerebrum: a combined Golgi, immunofluorescent and electron microscopic study". Brain Res. 148 (2): 295–311. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(78)90721-7. PMID 77708.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Schmechel DE, Rakic P (1979). "A Golgi study of radial glial cells in developing monkey telencephalon: morphogenesis and transformation into astrocytes". Anat. Embryol. 156 (2): 115–52. doi:10.1007/BF00300010. PMID 111580.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Misson JP, Edwards MA, Yamamoto M, Caviness VS (1988). "Identification of radial glial cells within the developing murine central nervous system: studies based upon a new immunohistochemical marker". Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 44 (1): 95–108. doi:10.1016/0165-3806(88)90121-6. PMID 3069243.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Voigt T (1989). "Development of glial cells in the cerebral wall of ferrets: direct tracing of their transformation from radial glia into astrocytes". J. Comp. Neurol. 289 (1): 74–88. doi:10.1002/cne.902890106. PMID 2808761.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Goldman SA, Zukhar A, Barami K, Mikawa T, Niedzwiecki D (1996). "Ependymal/subependymal zone cells of postnatal and adult songbird brain generate both neurons and nonneuronal siblings in vitro and in vivo". J. Neurobiol. 30 (4): 505–20. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199608)30:4<505::AID-NEU6>3.0.CO;2-7. PMID 8844514.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Riquelme R, Miralles C, De Blas A (15 December 2002). "Bergmann glia GABA(A) receptors concentrate on the glial processes that wrap inhibitory synapses". J. Neurosci. 22 (24): 10720–30. PMID 12486165.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yamada K, Watanabe M (2002). "Cytodifferentiation of Bergmann glia and its relationship with Purkinje cells". Anatomical science international / Japanese Association of Anatomists. 77 (2): 94–108. doi:10.1046/j.0022-7722.2002.00021.x. PMID 12418089.

- ^ a b c d Astrocytomas. (2010). Retrieved 2011, from IRSA: http://www.irsa.org/astrocytoma.html

- ^ a b Astrocytoma Tumors (2005, August). Retrieved 2011, from American Association of Neurological Surgeons: http://www.aans.org/Patient%20Information/Conditions%20and%20Treatments/Astrocytoma%20Tumors.aspx.

27. Halassa, M.M., Fellin, T., and Haydon, P.G. (2006) The tripartite synapse: roles for gliotransmission in health and disease. Trends in Mol. Sci 13, 54-63

28. White, F.A., Jung, H. and Miller, R.J. (2007) Chemokines and the pathophysiology of neuropathic pain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 20151-20158

29. Milligan, E.D. and Watson, L.R. (2009) Pathological and protective roles of glia in chronic pain. Neuron-Glia Interactions. 10, 23-36

30. Watkins, L.R., Milligan, E.D. and Maier, S.F. (2001) Glial activation: a driving force for pathological pain. Trends in Neurosci. 24, 450-455

31. Volterra, A. and Meldolesi, J. (2005) Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: the revolution continues. Nat. Rev Neurosci. 6, 626-640

35. Marc R. Freeman. Science 5 November 2010: Vol. 330 no. 6005 pp. 774–778. DOI: 10.1126/science.1190928

36.

37.

38.