Umoonasaurus: Difference between revisions

Slate Weasel (talk | contribs) m →Classification: Add year |

Slate Weasel (talk | contribs) →Classification: Add Benson et. al. (2013) |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

==Classification== |

==Classification== |

||

In 2003, the specimens that would later be assigned to ''Umoonasaurus'' were thought to represent a new species of ''[[Leptocleidus]]''.<ref name="Kear2003">{{cite journal|last1=Kear|first1=Benjamin P.|title=Cretaceous marine reptiles of Australia: a review of taxonomy and distribution|url=http://seaturtle.org/library/KearBP_2003c_CretaceousResearch.pdf|journal=Cretaceous Research|volume=24|issue=3|year=2003|pages=277–303|doi=10.1016/S0195-6671(03)00046-6}}</ref> In 2006, Kear and colleagues found ''Umoonasaurus'' to belong to the superfamily [[Pliosauroidea]] and be the most basal member of the family [[Rhomaleosauridae]]. They found the latter surprising, as ''Umoonasaurus'' was also identified as the last surviving member of that family. ''[[Leptocleidus]]'' was recovered as a more derived rhomaleosaurid, although it was still considered plausible that the two might be close relatives.<ref name="Kear2006"/> In 2008, Smith and Dyke found it to belong to [[Leptocleididae]] instead of Rhomaleosauridae, although still within Pliosauroidea.<ref name="Smith2008" /> A 2009 study by Druckenmiller and Russel recovered ''Umoonasaurus'' as a pliosauroid and a possible member of [[Polycotylidae]].<ref name="Druckenmiller2009">{{cite journal|last1=Druckenmiller|first1=Patrick S.|last2=Russel|first2=Anthony P.|year=2009|title=Earliest North American occurrence of Polycotylidae (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous (Albian) Clearwater Formation, Alberta, Canada|journal=Journal of Paleontology|volume=83|issue=6|pages=981–989|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228902520|doi=10.1666/09-014.1}}</ref> In 2010, Ketchum and Benson found ''Umoonasaurus'' to be a member of Leptocleididae, although finding that family to belong to [[Plesiosauroidea]] instead of Pliosauroidea.<ref name="Ketchum2010">{{cite journal|last1=Ketchum|first1=H. F. |last2=Benson|first2=R. B. J. |lastauthoramp=yes |year=2010 |title=Global interrelationships of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) and the pivotal role of taxon sampling in determining the outcome of phylogenetic analyses |journal=Biological Reviews |volume=85 |issue=2 |pages=361–392 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00107.x |pmid=20002391}}</ref> ''Umoonasaurus'' was also recovered as a leptocleidid by Druckenmiller and Knutsen in 2012, who found Leptocleididae to belong to Pliosauroidea once again.<ref name="Druckenmiller2012">{{cite journal|last1=Druckenmiller|first1=P.S.|last2=Knutsen|first2=E.M.|title=Phylogenetic relationships of Upper Jurassic (Middle Volgian) plesiosaurians (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Agardhfjellet Formation of central Spitsbergen, Norway|journal=Norwegian Journal of Geology|volume=92|pages=277–284|year=2012|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267927834}}</ref> In 2015, Parrilla-Bel and Canudo found ''Umoonasaurus'' to be a leptocleidid, and in turn finding Leptocleididae to belong to |

In 2003, the specimens that would later be assigned to ''Umoonasaurus'' were thought to represent a new species of ''[[Leptocleidus]]''.<ref name="Kear2003">{{cite journal|last1=Kear|first1=Benjamin P.|title=Cretaceous marine reptiles of Australia: a review of taxonomy and distribution|url=http://seaturtle.org/library/KearBP_2003c_CretaceousResearch.pdf|journal=Cretaceous Research|volume=24|issue=3|year=2003|pages=277–303|doi=10.1016/S0195-6671(03)00046-6}}</ref> In 2006, Kear and colleagues found ''Umoonasaurus'' to belong to the superfamily [[Pliosauroidea]] and be the most basal member of the family [[Rhomaleosauridae]]. They found the latter surprising, as ''Umoonasaurus'' was also identified as the last surviving member of that family. ''[[Leptocleidus]]'' was recovered as a more derived rhomaleosaurid, although it was still considered plausible that the two might be close relatives.<ref name="Kear2006"/> In 2008, Smith and Dyke found it to belong to [[Leptocleididae]] instead of Rhomaleosauridae, although still within Pliosauroidea.<ref name="Smith2008" /> A 2009 study by Druckenmiller and Russel recovered ''Umoonasaurus'' as a pliosauroid and a possible member of [[Polycotylidae]].<ref name="Druckenmiller2009">{{cite journal|last1=Druckenmiller|first1=Patrick S.|last2=Russel|first2=Anthony P.|year=2009|title=Earliest North American occurrence of Polycotylidae (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous (Albian) Clearwater Formation, Alberta, Canada|journal=Journal of Paleontology|volume=83|issue=6|pages=981–989|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228902520|doi=10.1666/09-014.1}}</ref> In 2010, Ketchum and Benson found ''Umoonasaurus'' to be a member of Leptocleididae, although finding that family to belong to [[Plesiosauroidea]] instead of Pliosauroidea.<ref name="Ketchum2010">{{cite journal|last1=Ketchum|first1=H. F. |last2=Benson|first2=R. B. J. |lastauthoramp=yes |year=2010 |title=Global interrelationships of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) and the pivotal role of taxon sampling in determining the outcome of phylogenetic analyses |journal=Biological Reviews |volume=85 |issue=2 |pages=361–392 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00107.x |pmid=20002391}}</ref> ''Umoonasaurus'' was also recovered as a leptocleidid by Druckenmiller and Knutsen in 2012, who found Leptocleididae to belong to Pliosauroidea once again.<ref name="Druckenmiller2012">{{cite journal|last1=Druckenmiller|first1=P.S.|last2=Knutsen|first2=E.M.|title=Phylogenetic relationships of Upper Jurassic (Middle Volgian) plesiosaurians (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Agardhfjellet Formation of central Spitsbergen, Norway|journal=Norwegian Journal of Geology|volume=92|pages=277–284|year=2012|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267927834}}</ref> A 2013 study by Benson and colleagues found ''Umoonasaurus'' to be a close relative of ''Leptocleidus'' and to belong to [[Leptocleidia]], which was found to belong to Plesiosauroidea.<ref name="Benson2015">{{cite journal|last1=Benson|first1=Roger B. J.|last2=Evans|first2=Mark|last3=Smith|first3=Adam S.|last4=Sassoon|first4=Judyth|last5=Moore-Faye|first5=Scott|last6=Ketchum|first6=Hilary F.|last7=Forrest|first7=Richard|year=2013|title=A Giant Pliosaurid Skull from the Late Jurassic of England|journal=PLoS ONE|volume=8|issue=5|pages=e65989|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0065989}}</ref> In 2015, Parrilla-Bel and Canudo found ''Umoonasaurus'' to be a leptocleidid, and in turn finding Leptocleididae to belong to Leptocleidia, which was once again recovered as a member of Plesiosauroidea.<ref name="Parrilla-Bel2015">{{cite journal|last1=Parrilla-Bel|first1=Jara|first2=José Ignacio|last2=Canudo|title=On the presence of plesiosaurs in the Blesa Formation (Barremian) in Teruel (Spain)|journal=Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen|volume=278|issue=2|year=2015|pages=213–227|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282942268|doi=10.1127/njgpa/2015/0526}}</ref> |

||

{{col-begin|width=100%}} |

{{col-begin|width=100%}} |

||

Revision as of 11:53, 15 August 2019

| Umoonasaurus Temporal range: Early Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

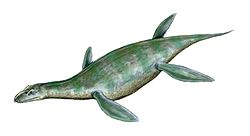

| Umoonasaurus demoscyllus from the Early Cretaceous of Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Umoonasaurus

|

| Species: | U. demoscyllus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Umoonasaurus demoscyllus Kear, Schroeder & Lee, 2006

| |

Umoonasaurus is an extinct genus of plesiosaur[1] belonging to the family Leptocleididae.[2] This genus lived approximately 115 million years ago (Aptian-Albian) in shallow seas covering parts of what is now Australia. It was a relatively small animal around 2.5 m (8 ft) long. An identifying trait of Umoonasaurus is three crest-ridges on its skull.[3]

Discovery and Naming

The holotype of Umoonasaurus demoscyllus is AM F99374 is an opalized skeleton that has been nicknamed "Eric." It was discovered in the Zorba Extension Opal Field near the town of Coober Pedy, and is very well preserved. Three other specimens have been referred to this species. SAM P2381, discovered in the Andamooka opal fields, is another opalized specimen. SAM 31050 was discovered in the Curdimurka area near Lake Eyre, and SAM P410550, a juvenile specimen, comes from the Neales River region, near the town of Oodnadatta.[3] Another juvenile specimen, SAM P15980, was also later referred to this species. All known specimens come from the Bulldog Shale.[4]

The generic name is a combination of the Antakirinja name for the Coober Pedy region, Umoona, and the Greek word sauros, meaning "lizard." The specific name comes from the Greek words demos and scyll, meaning "of the people" and "sea monster," respectively. The specific name refers to the public donations given to acquire the specimen.[3]

Description

Umoonasaurus is a small plesiosaur, a four-flippered marine reptile. The holotype is estimated to have been 2.5 meters (8.2 ft) long, while the juvenile specimen SAM P15980 was only 70 centimetres (2.3 ft) long at maximum.[4] Umoonasaurus is unusual in possessing a combination of primitive and derived characters.[3]

Umoonasaurus had a small, triangular head with a length of 22.2 centimeters (8.7 in) and a width of 13 centimeters (5.1 in). A tall, narrow crest is present along the middle of the anterior end of the skull. Two other ridges are present above the orbits. The premaxilla bears a dental rosette with five tooth sockets. These would have held long, sharp teeth. Each maxilla bears at least 10 tooth sockets. The teeth in positions 4 to 6 would have been very large, while the rest of the teeth would have been smaller and more gracile. The external nares are very small and positioned close to the orbits. While incomplete, the temporal fenestrae would have likely occupied one third of the length of the skull. The anterior skull roof (composed of the parietals) is lanceolate (shaped like a lance head). The pineal foramen (a depression between the orbits and the temporal fenestrae) is triangular and has raised edges.[3]

Classification

In 2003, the specimens that would later be assigned to Umoonasaurus were thought to represent a new species of Leptocleidus.[5] In 2006, Kear and colleagues found Umoonasaurus to belong to the superfamily Pliosauroidea and be the most basal member of the family Rhomaleosauridae. They found the latter surprising, as Umoonasaurus was also identified as the last surviving member of that family. Leptocleidus was recovered as a more derived rhomaleosaurid, although it was still considered plausible that the two might be close relatives.[3] In 2008, Smith and Dyke found it to belong to Leptocleididae instead of Rhomaleosauridae, although still within Pliosauroidea.[2] A 2009 study by Druckenmiller and Russel recovered Umoonasaurus as a pliosauroid and a possible member of Polycotylidae.[6] In 2010, Ketchum and Benson found Umoonasaurus to be a member of Leptocleididae, although finding that family to belong to Plesiosauroidea instead of Pliosauroidea.[1] Umoonasaurus was also recovered as a leptocleidid by Druckenmiller and Knutsen in 2012, who found Leptocleididae to belong to Pliosauroidea once again.[7] A 2013 study by Benson and colleagues found Umoonasaurus to be a close relative of Leptocleidus and to belong to Leptocleidia, which was found to belong to Plesiosauroidea.[8] In 2015, Parrilla-Bel and Canudo found Umoonasaurus to be a leptocleidid, and in turn finding Leptocleididae to belong to Leptocleidia, which was once again recovered as a member of Plesiosauroidea.[9]

|

Topology recovered by Druckenmiller and Russell, 2009.[6]

|

Topology of Leptocleidia recovered by Parrilla-Bel and Canudo, 2015.[9]

|

Paleoenvironment

All known Umoonasaurus come from the Bulldog Shale, a member of the Maree Subgroup located in South Australia.[3] The Bulldog Shale is composed of carbnaceous mudstone and shale beds, and represents a shallow epicontinental sea. It would have been located at a latitude of approximately 70° S, within the Lower Cretaceous high latitude zone (polar regions). The presence of glendonite, ice-rafted boulders, and coniferous driftwood with dense growth rings indicate a seasonal climate with near-freezing temperatures.[10] This implies that Umoonasaurus was probably able to tolerate these cold conditions.[3] The Bulldog Shale has yielded fossils of invertebrates, bony fish, chimaeras, and reptiles.[10] Among these reptiles are other plesiosaurs, including the possible aristonectine elasmosaurid Opallionectes, the giant pliosaurid Kronosaurus, and polycotylid-like specimens, in addition to Platypterigius, an ichthyosaur.[4] Archosaur fossils from the Bulldog shale are rare, and are represented by the small tetanuran theropod Kakuru, and several indeterminate specimens, some of which can be assigned to Dinosauria.[11]

See also

References

- ^ a b Ketchum, H. F.; Benson, R. B. J. (2010). "Global interrelationships of Plesiosauria (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) and the pivotal role of taxon sampling in determining the outcome of phylogenetic analyses". Biological Reviews. 85 (2): 361–392. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00107.x. PMID 20002391.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Smith, AS; Dyke, GJ (2008). "The skull of the giant predatory pliosaur Rhomaleosaurus cramptoni: implications for plesiosaur phylogenetics". Naturwissenschaften. 95 (10): 975–980. Bibcode:2008NW.....95..975S. doi:10.1007/s00114-008-0402-z. PMID 18523747.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kear, Benjamin P; Schroeder, Natalie I.; Lee, Michael S.Y. (2006). "An archaic crested plesiosaur in opal from the Lower Cretaceous high-latitude deposits of Australia". Biology Letters. 2 (4): 615–619. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0504. PMC 1833998. PMID 17148303.

- ^ a b c Kear, Benjamin P. (2016). "Cretaceous marine amniotes of Australia: perspectives on a decade of new research" (PDF). Memoirs of Museum Victoria. 74: 17–28. doi:10.24199/j.mmv.2016.74.03.

- ^ Kear, Benjamin P. (2003). "Cretaceous marine reptiles of Australia: a review of taxonomy and distribution" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 24 (3): 277–303. doi:10.1016/S0195-6671(03)00046-6.

- ^ a b Druckenmiller, Patrick S.; Russel, Anthony P. (2009). "Earliest North American occurrence of Polycotylidae (Sauropterygia: Plesiosauria) from the Lower Cretaceous (Albian) Clearwater Formation, Alberta, Canada". Journal of Paleontology. 83 (6): 981–989. doi:10.1666/09-014.1.

- ^ Druckenmiller, P.S.; Knutsen, E.M. (2012). "Phylogenetic relationships of Upper Jurassic (Middle Volgian) plesiosaurians (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) from the Agardhfjellet Formation of central Spitsbergen, Norway". Norwegian Journal of Geology. 92: 277–284.

- ^ Benson, Roger B. J.; Evans, Mark; Smith, Adam S.; Sassoon, Judyth; Moore-Faye, Scott; Ketchum, Hilary F.; Forrest, Richard (2013). "A Giant Pliosaurid Skull from the Late Jurassic of England". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e65989. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065989.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Parrilla-Bel, Jara; Canudo, José Ignacio (2015). "On the presence of plesiosaurs in the Blesa Formation (Barremian) in Teruel (Spain)". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 278 (2): 213–227. doi:10.1127/njgpa/2015/0526.

- ^ a b Zammit, Maria; Kear, Benjamin P. (2011). "Healed bite marks on a Cretaceous ichthyosaur" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (4): 859–863. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0117.

- ^ Barrett, Paul M.; Kear, Benjamin P.; Benson, Roger B.J. (2010). "Opalized archosaur remains from the Bulldog Shale (Aptian: Lower Cretaceous) of South Australia" (PDF). Alcheringa. 34: 1–9. ISSN 0311-5518.