Anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

Anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea is complex and multifaceted. Anti-Japanese attitudes in Korea can be traced back to the effects of Japanese pirate raids in the Middle Ages and later of the 1592−98 Japanese invasions of Korea, but are largely a product of the period of Japanese rule in Korea from 1910–45 and subsequent education. This sentiment may also be at least to some extent influenced by issues related to Koreans in Japan.[citation needed]

Waegu (Japanese piracy)

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2010) |

Waegu (倭寇) is the Korean term for Japanese pirates who raided the coastlines of China and Korea from the 13th century onwards.

Japanese pirate raids on the Korean peninsula are recorded as early as 414 on the Gwanggaeto Stele. From the 13th to the mid-16th century, Waegu raids were particularly considered a nuisance in Korea, disrupting commerce 529 times in the Goryeo period, and 312 times in the Joseon period.

In modern times, the term Waegu has been used in Korea as a derogatory or propagandistic term for Japanese invaders.

Japanese invasions of Korea

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2011) |

During this time the invading Japanese dismembering more than 20,000 noses and ears from Koreans and bringing them back to Japan to create nose tombs as war trophies.[1][2][3] In addition after the war, Korean artisans including potters were kidnapped by Hideyoshi's order to cultivate Japan's arts and culture. The abducted Korean potters played important roles to be a major factor in establishing new types of pottery such as Satsuma, Arita, and Hagi ware.[4][5][6] This would cause tension because the Koreans feel that their culture was stolen during this time by Japan.[citation needed]

Effect of Japanese rule in Korea

Korea was ruled by the Japanese Empire from 1910 to 1945. Japan's involvement began with the 1876 Treaty of Ganghwa during the Joseon Dynasty of Korea and increased over the following decades with the Gapsin Coup (1882), the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) , the assassination of Empress Myeongseong at the hands of Japanese agents in 1895,[7] the establishment of the Korean Empire (1897), the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05), the Taft-Katsura Agreement (1905), and culminating with the 1905 Eulsa Treaty, removing Korean autonomous diplomatic rights, and the 1910 Annexation Treaty, both of which were eventually declared null and void by the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea in 1965.

Japan's cultural assimilation policies

The Japanese colonization of Korea has been mentioned as the case in point of "cultural genocide" by Yuji Ishida on February 23, 2004.[8] The colonial government put into practice the suppression of Korean culture and language in an "attempt to root out all elements of Korean culture from society".[8]"Focus was heavily and intentionally placed upon the psychological and cultural element in Japan's colonial policy, and the unification strategies adopted in the fields of culture and education were designed to eradicate the individual ethnicity of the Korean race."[8]

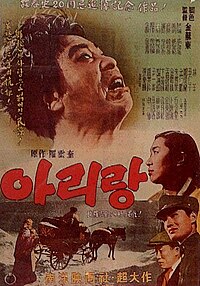

After the annexation of Korea, Japan enforced a cultural assimilation policy. The Korean language was removed from the required school subjects in Korea in 1936.[9] Japan imposed the family name system along with civil law (Sōshi-kaimei) and attendance at Shinto shrines. Koreans were forbidden to write or speak the Korean language in schools, businesses, or public places under penalty of death.[10] However, many Korean language movies were screened in the Korean peninsula.

In addition, Koreans were angry over Japanese alteration and destruction of various Korean monuments including Gyeongbok Palace (경복궁, Gyeongbokgung) and the revision of documents that portrayed the Japanese in a negative light.

Independence Movement

On March 1, 1919, anti-Japanese rule protests were held all across the country to demand independence. About 2 million Koreans actively participated in what is now known as the March 1st Movement. A Declaration of Independence [1], patterned after the American version, was read by teachers and civic leaders in tens of thousands of villages throughout Korea: “Today marks the declaration of Korean independence. There will be peaceful demonstrations all over Korea. If our meetings are orderly and peaceful, we shall receive the help of President Wilson and the great powers at Versailles, and Korea will be a free nation.” [11] Japan repressed independence movement by military power. In one well attested incident, villagers were herded into the local church which was then set on fire.[12] The official Japanese count of casualties include 553 killed, 1,409 injured, and 12,522 arrested, but the Korean estimates are much higher: over 7,500 killed, about 15,000 injured, and 45,000 arrested.[13]

Comfort Women

While estimates vary, Korea states that many Korean women were kidnapped and coerced by the Japanese authorities into military prostitution, euphemistically called "comfort women" (위안부, wianbu). [2][14] Some Japanese historians, such as Yoshiaki Yoshimi, using the diaries and testimonies of military officials as well as official documents from Japan and archives of the Tokyo tribunal, have argued that the Imperial Japanese military was either directly or indirectly involved in coercing, deceiving, luring, and sometimes kidnapping young women throughout Japan’s Asian colonies and occupied territories.[citation needed] However Japanese historian Ikuhiko Hata stated that there was no organized forced recruitment of comfort women by Japanese government or military. [3]

Contemporary issues

Generally North Korea-based anti-Japanese sentiment is understood to be fueled by Communist propaganda from the government, thus attempts to measure it among ordinary people is impossible given the country's political system. The following statements thus apply to South Korea only.

Current situation in the South

A 2000 CNN ASIANOW article described popularity of Japanese culture among younger South Koreans as "unsettling" for older Southerners who remember the occupation by the Japanese.[15]

In the South, collaborators to the Japanese colonial government, called chinilpa (친일파), are generally recognized as national traitors. The South Korean National Assembly passed the Special law to redeem pro-Japanese collaborators' property on December 8, 2005 and the law was enacted on December 29, 2005. In 2006, The National Assembly of South Korea formed a Committee for the Inspection of Property of Japan Collaborators. The aim was to reclaim property inappropriately gained by cooperation with the Japanese government during colonialization. The project was expected to satisfy Koreans' demands that property acquired by collaborators under the Japanese colonial authorities be returned.[16]

While some Koreans expressed hope that former Japanese Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama would handle Japanese-Korean relations in a more agreeable fashion that previous conservative administrations, a small group of protesters in Seoul held an anti-Japanese rallying on October 8, 2009 previous to his arrival. The protests called for Japanese apologies for World War II incidents and included destruction of a Japanese flag.[17]

Japanese textbook revisionism

Anti-Japanese sentiment is also due to the Japanese government's textbook revisionism. On June 26, 1982 the textbook screening process in Japan came under scrutiny when the media of Japan and its neighboring countries gave extensive coverage to changes required by the Minister of Education. Experts from the ministry sought to soften textbook references to Japanese aggression before and during World War II. The Japanese invasion of China in 1937, for example, was modified to "advance." Passages describing the fall of Nanking justified the Japanese atrocities by describing the acts as a result of Chinese provocations. Pressure from China successfully led the Ministry of Education to adopt a new authorization criterion - the "Neighboring Country Clause" (近隣諸国条項) - stating: "textbooks ought to show understanding and seek international harmony in their treatment of modern and contemporary historical events involving neighboring Asian countries."[18]

In 2006, Japanese textbooks wrote that the Liancourt Rocks is Japanese territory. The head of the South Korean Ministry of Education, Kim Shinil, sent a letter of protest to Bunmei Ibuki, the Minister of Education, on May 9, 2007.[19] In a speech marking the 88th anniversary of the March 1 Independence Movement, South Korean President Roh Moo-hyun called for Japan to correct their school textbooks on controversial topics ranging from "inhumane rape of comfort women" to "the Korean ownership of the Liancourt Rocks".[20]

National relations

Yasuhiro Nakasone discontinued visits to Yasukuni Shrine due to the People's Republic of China's requests in 1986. However, Former Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi resumed visits to Yasukuni Shrine on August 13, 2001. He visited the shrine six times as Prime Minister, stating that he was "paying homage to the servicemen who died for defense of Japan."[21] These visits drew strong condemnation and protests from Japan's neighbors, mainly China. [22] As a result, China and South Korea refused to meet with Koizumi, and there were no mutual visits between Chinese and Japanese leaders after October 2001 and between South Korean and Japanese leaders after June 2005. Former President of South Korea Roh Moo-hyun suspended all summit talks between South Korea and Japan.[23]

Education

A large number of anti-Japanese images made by school children from Gyeyang Middle School, many of which depicting acts of violence against Japan, were displayed in Gyulhyeon Station as part of a school art project.[24][25][26]

According to a survey conducted by Korean Immigrant Workers Human Rights Center in 2006, 34.1% of the primary school students in Incheon region answered that "Japanese should be expelled from Korea" and the rate was considerably higher compared to Chinese (8.7%), black Africans (8.7%), East Asians (5.0%), black Americans (4.3%), and white Americans (2.3%).[27][28]

Professor Park Cheol-Hee of Gyeongin National University of Education pointed out that there were many descriptions regarding other nations as inferior to emphasize the superiority of Korean culture, and Japan is consistently described as culturally inferior.[29][30] A survey found that 60% middle school students and 51% of high school students in South Korea view the descriptions about Japan and China in the current Korean history textbooks as biased.[31]

Appearance in South Korean popular culture

- The General's Son (장군의 아들; Janggun eui Adeul) - 1990 movie set in Korea under Japanese rule, in which Kim Du-han (then a gangster) attacks Japanese yakuza. Two sequels were released in 1991 and 1992.

- Virus Imjin War (바이러스 임진왜란; Baireoseu Imjin Waeran) - 1990 novel by Lee Sun-Soo (이성수). Japan tries to invade Korea using biological warfare named Hideyoshi Virus only to fail.

- The Mugunghwa Has Bloomed (무궁화 꽃이 피었습니다; Mugunghwa ggoti pieotseubnida) - A popular novelist Gim Jinmyeong (김진명) wrote this novel in 1993. (Mugunghwa, known as Hibiscus syriacus, is the national flower of South Korea.) In this novel, North and South Korea together develop a nuclear weapon, which is dropped off the coast of Japan as a symbolic warning. This novel was criticized for a blatantly inaccurate depiction of Korean-American particle physicist Benjamin W. Lee (Lee Whiso 이휘소) as a nationalistic nuclear physicist; in this novel, Lee cuts his own leg flesh in order to hide the blueprint of a nuclear weapon, which is secretly transferred to the South Korean government. Lee's family sued Kim for defamation. The novel became a major bestseller, and was made into a film in 1995. ([4])

- Phantom: The Submarine - A movie in which a secret South Korean nuclear submarine falls under the mercy of a charismatic half-mad captain, who attempts to carpet Japanese cities with nuclear weapons. This movie won six "Academy Awards" in South Korea in 1999. ([5])

- There Is No Japan (일본은 없다; Ilboneun Eopta) - Travelogue written by Grand National Party spokeswoman Jeon Yeook (전여옥) in 1994, based upon her experiences in Japan as a KBS correspondent. She compares South Korea with Japan, praises South Korean excellence, and describes the Japanese as an incapable people.

- Hyeomillyu (혐일류; The Hate Japan Wave) - Korean cartoonist Yang Byeong-seol's (양병설) response to the book Manga Kenkanryu (The Hating Korea Wave).

- Hanbando (한반도) - The South Korea government exposes the misinterpretation of the history of Japanese Government, and Japanese Government does the apology and compensation to a South Korea.

- Nambul: War Stories (남벌) - Nambul is a manhwa series of the military drama genre written by Lee Hyun-se which started in 1994. The story relates from various levels (political to personal) an imaginary conflict between Korea and Japan at an unspecified time in the near future.

References

- ^ Sansom, George (1961). A History of Japan, 1334-1615. Stanford studies in the civilizations of eastern Asia. Stanford University Press. p. 360. ISBN 0-8047-0525-9.

Visitors to Kyoto used to be shown the Minizuka or Ear Tomb, which contained, it was said, the ears of those 38,000, sliced off, suitably pickled, and sent to Kyoto as evidence of victory.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Saikaku, Ihara (1990). The Great Mirror of Male Love. Stanford Nuclear Age Series. Stanford University Press. p. 324. ISBN 0-8047-1895-4.

The Great Mirror of Male Love. "Mimizuka, meaning "ear tomb", was the place Toyotomi Hideyoshi buried the ears taken as proof of enemy dead during his brutal invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1997.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kristof, Nicholas D. (September 14, 1997), "Japan, Korea and 1597: A Year That Lives in Infamy", The New York Times, New York, retrieved 2008-09-22

- ^ Purple Tigress (August 11, 2005). "Review: Brighter than Gold - A Japanese Ceramic Tradition Formed by Foreign Aesthetics". BC Culture. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ "Muromachi period, 1392-1573". Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2002. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

1596 Toyotomi Hideyoshi invades Korea for the second time. In addition to brutal killing and widespread destruction, large numbers of Korean craftsmen are abducted and transported to Japan. Skillful Korean potters play a crucial role in establishing such new pottery types as Satsuma, Arita, and Hagi ware in Japan. The invasion ends with the sudden death of Hideyoshi.

- ^ John Stewart Bowman (2002). Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. 170p. ISBN 0-231-11004-9.

- ^ See Russian eyewitness account of surrounding circumstances at http://koreaweb.ws/ks/ksr/queenmin.txt

- ^ a b c ""Cultural Genocide" and the Japanese Occupation of Korea". Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ^ Template:Ja icon Instruction concerning the Korean education Decree No.229 (1911) 朝鮮教育令(明治44年勅令第229号), Nakano Bunko. Archived 2009-10-25.

- ^ Cumings, Bruce G. "The Rise of Korean Nationalism and Communism". A Country Study: North Korea. Library of Congress. Call number DS932 .N662 1994.

- ^ The Samil (March First) Independence Movement

- ^ Dr. James H. Grayson, "Christianity and State Shinto in Colonial Korea: A Clash of Nationalisms and Religious Beliefs" DISKUS Vol.1 No.2 (1993) pp.13-30.

- ^ Bruce Cummings, Korea's Place in the Sun: A Modern History, W.W. Norton & Company, 1997, New York, p. 231, ISBN 0-393-31681-5.

- ^ Yoshimi Yoshiaki, 従軍慰安婦 (Comfort Women). Translated by Suzanne O'Brien. Columbia University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-231-12032-X

- ^ "Japanese pop culture invades South Korea." CNN.

- ^ "Assets of Japan Collaborators to Be Seized", The Korea Times, August 13, 2006.

- ^ "SOUTH KOREA: Anti-Japanese rally in Seoul ahead of Japanese prime minister's visit", ITN Source, October 9, 2009.

- ^ Murai Atsushi, "Abolish the Textbook Authorization System," Japan Echo, (Aug. 2001): 28.

- ^ "Ed. Minister Protests Distortions in Japanese Textbooks", Chosun Ilbo, May.10,2007.

- ^ "Roh Calls on Japan to Respect Historical Truth", Chosun Ilbo, Mar.2,2007.

- ^ Template:Ja icon "小泉総理インタビュー 平成18年8月15日" (Official interview of Koizumi Junichiro on August 15, 2006), Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, August 15, 2006.

- ^ Don Kirk, "Koizumi Move Sparks Anger In China and South Korea" International Herald Tribune, August 14, 2001.

- ^ Template:En icon and Template:Ko icon "노무현 대통령, “고이즈미 일본총리가 신사참배 중단하지 않으면 정상회담도 없을 것” (영문기사 첨부)", Voice of America, 03/17/2006.

- ^ "Children's drawings in the subway!, How cute", Jun 13 2005, "More children's drawings displayed in the subway., The second time is just like the first", Jun 18 2005, A passing moment in the life of Gord.

- ^ Template:Ko icon "외국인들 “한국인 반일 감정 지나치다”", Daum, 2005-10-1.

- ^ James Card "A chronicle of Korea-Japan 'friendship'", Asia Times, Dec 23, 2005, "The most disturbing images of the year were drawings on exhibit at Gyulhyeon Station on the Incheon subway line..."

- ^ Template:Ko icon 초등생에 외국인 선호도 물으니…美·中·동남아·日 순, The Kukmin Daily, 2006.12.13.

- ^ Template:Ko icon 인천지역 초등학생의 외국인 인식실태 및 다문화인권교육 워크샵개최, Korean Immigrant Workers Human Rights Center, 2006-12-12.

- ^ Template:Ko icon 초등교과서, 고려때 ‘23만 귀화’ 언급도 안해, The Kyunghyang Shinmun/Empas news, 2007-08-21.

- ^ Template:Ko icon 초등 4~6학년 교과서, 단일민족·혈통 지나치게 강조, The Kyunghyang Shinmun, 2007/08/21.

- ^ Template:Ko icon 중.고교생 60% "역사교과서 문제있다", Yonhap News, 2007/09/14.