Arthur W. Radford

Arthur W. Radford | |

|---|---|

Admiral Arthur W. Radford as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff | |

| Born | 27 February 1896 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | 17 August 1973 (aged 77) Bethesda, Maryland, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1916–1957 |

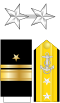

| Rank | Admiral |

| Commands | Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff United States Pacific Fleet Vice Chief of Naval Operations Second Task Fleet Carrier Division Eleven Aviation Training Division Naval Air Station Seattle VF-1B |

| Battles / wars |

|

| Awards | Navy Distinguished Service Medal (4) Legion of Merit (2) Order of Fiji Companion of the Order of the Bath (United Kingdom) |

| Signature | |

Arthur William Radford (27 February 1896 – 17 August 1973) was an admiral and naval aviator of the United States Navy. In over 40 years of military service, Radford held a variety of positions including the vice chief of Naval Operations, commander of the United States Pacific Fleet and later the second chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

With an interest in ships and aircraft from a young age, Radford saw his first sea duty aboard the battleship USS South Carolina during World War I. In the inter-war period he earned his pilot wings and rose through the ranks in duties aboard ships and in the Bureau of Aeronautics. After the U.S. entered World War II, he was the architect of the development and expansion of the Navy's aviator training programs in the first years of the war. In its final years he commanded carrier task forces through several major campaigns of the Pacific War.

Noted as a strong-willed and aggressive leader, Radford was a central figure in the post-war debates on U.S. military policy, and was a staunch proponent of naval aviation. As commander of the Pacific Fleet, he defended the Navy's interests in an era of shrinking defense budgets, and was a central figure in the "Revolt of the Admirals," a contentious public fight over policy. As Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, he continued to advocate for aggressive foreign policy and a strong nuclear deterrent in support of the "New Look" policy of President Dwight Eisenhower.

Retiring from the military in 1957, Radford continued to be a military adviser to several prominent politicians until his death in 1973. For his extensive service, he was awarded many military honors, and was the namesake of the Spruance-class destroyer USS Arthur W. Radford.

Early life

[edit]Arthur William Radford was born on 27 February 1896 in Chicago, Illinois, to John Arthur Radford, a Canadian-born electrical engineer, and Agnes Eliza Radford (née Knight).[1] The eldest of four children, he was described as bright and energetic in his youth.[2] When Arthur was six years old the family moved to Riverside, Illinois, where his father took a job as a managing engineer with Commonwealth Edison Company. John Radford managed the first steam turbine engines in the United States, at the Fisk Street Generating Station.[2]

Arthur began his school years at Riverside Public School, where he expressed an interest in the United States Navy from a young age.[2] He gained an interest in aviation during a visit to the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis, Missouri.[3] By fourth grade, he frequently drew detailed cross-section diagrams of the USS Maine. He was shy, but performed very well in school. In mid-1910, Radford moved with his family to Grinnell, Iowa, and attended Grinnell High School for a year and a half, before deciding to apply to the United States Naval Academy. He obtained the local congressman's recommendation for an appointment to the academy, and was accepted. After several months of tutoring at Annapolis, Maryland, he entered the academy in July 1912, at the age of sixteen.[2]

Although Radford's first year at the academy was mediocre he applied himself to his studies in his remaining years there.[2] He participated in summer cruises to Europe in 1913 and 1914 and passed through the Panama Canal to San Francisco in 1916.[3] Radford, known as "Raddie" to his fellow students, graduated 59th of 177 in the class of 1916, and was commissioned as an ensign in the U.S. Navy during the First World War.[2]

Military career

[edit]Radford's first duty was aboard the battleship USS South Carolina,[2][4] as it escorted a transatlantic convoy to France in 1918.[5] In his second post he was an aide-de-camp to a battleship division commander, and in his third, a flag lieutenant for another battleship division commander.[2]

In 1920, Radford reported to Pensacola, Florida, for flight training,[2] and was promoted to lieutenant soon thereafter. During the 1920s and 1930s his sea duty alternated among several aircraft squadrons, fleet staffs, and tours in the U.S. with the Bureau of Aeronautics.[2] It was during this time, while he served under Rear Admiral William Moffett, that he frequently interacted with politicians and picked up the political acumen that would become useful later in his career. While he did not attend the Naval War College, as other rising officers did, Radford established himself as an effective officer who would speak his mind frankly, even to superiors.[6]

Radford achieved the rank of lieutenant commander by 1927,[5] and served with aircraft units aboard USS Colorado, USS Pennsylvania, and USS Wright.[4] In 1936, he was promoted to commander[5] and took charge of fighter squadron VF-1B aboard USS Saratoga. By 1938, he was given command of Naval Air Station Seattle in Seattle, Washington. On 15 April 1938, while flying Grumman SF-1, BuNo 9465, CDR Radford suffered a noseover mishap at Oakland Airport following a mechanical failure of the landing gear. Radford and passenger ACMM S.H. Ryan were uninjured and the aircraft was repaired.[4] On 22 April 1939, he married Miriam J. (Ham) Spencer at Vancouver Barracks, Washington. Spencer (1895–1997) was a daughter of George Ham of Portland, Oregon,[7] and the former wife of (1) Albert Cressey Maze (1891–1943), with whom she had a son, Robert Claude Maze Sr., Major, USMC who was killed in action in 1945 and (2) Earl Winfield Spencer Jr. In May 1940, Radford was appointed executive officer of the USS Yorktown, a post he served in for one year.[2]

In July 1941, Radford was appointed commander of the Naval Air Station in Trinidad, British West Indies. He protested this appointment because he feared he would remain there for years, sidelined as World War II loomed.[2] He only remained in this station for three months, following an organizational shift in the Bureau of Aeronautics. By mid-1941, thanks to a large expansion in the naval aviator program, squadrons could no longer train newly arrived aviators. Further, at that time, the vast difference in the performance of combat aircraft over training aircraft meant that pilots needed more time in combat aircraft before becoming proficient in them. Radford was subsequently visited by Artemus L. Gates, Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Air. The latter was so impressed that he ordered Rear Admiral John H. Towers, chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, to transfer Radford to a newly formed training division.[8]

World War II

[edit]Aviation Training Division

[edit]Radford took command of the Aviation Training Division in Washington, D.C., on 1 December 1941, seven days before the attack on Pearl Harbor that brought the United States into World War II.[8] He was appointed as Director of Aviation Training for both the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and the Bureau of Navigation;[9] the double appointment helped to centralize training coordination for all naval aviators. With the U.S. mobilizing for war, Radford's office worked long hours six days a week in an effort to build up the necessary training infrastructure as quickly as possible. For several months, this around-the-clock work took up all of his time, and he later noted that walking to work was his only form of exercise for several months. During this time, he impressed colleagues with a direct and no-nonsense approach to work, while maintaining a demeanor that made him easy to work for.[8] He was promoted to captain soon after.[5]

Throughout 1942 he established and refined the administrative infrastructure for aviation training. Radford oversaw the massive growth of the training division, establishing separate sections for administration; Physical Training Service Schools; and training devices; and sections to train various aviators in flight, aircraft operation, radio operation, and gunnery. The section also organized technical training and wrote training literature. He also engineered the establishment of four field commands for pilot training. Air Primary Training Command commanded all pre-flight schools and Naval reserve aviation bases in the country. Air Intermediate Training Command administered Naval Air Station Pensacola and Naval Air Station Corpus Christi where flight training was conducted. Air Operational Training Command was in charge of all education of pilots between pilot training and their first flying assignments. Finally, Air Technical Training Command trained enlisted men for support jobs in aviation such as maintenance, engineering, aerography, and parachute operations. Radford sought to integrate his own efficient leadership style into the organization of these schools.[10]

Radford was noted for thinking progressively and innovatively to establish the most effective and efficient training programs. He sought to integrate sports conditioning programs into naval aviator training. Radford brought in athletic directors from Ohio State University, Harvard University and Penn State University under football player and naval aviator Tom Hamilton, to whom he gave the remit to develop the conditioning programs. Radford also suggested integrating women into intricate but repetitive tasks, such as running flight simulators. When commanders rejected the idea of bringing women into the service, he convinced Congressman Carl Vinson, chair of the House Naval Affairs Committee of the merit of the idea. This effort eventually led to the employment of the "Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service", and 23,000 WAVES would assist in aeronautical training in the course of the war. Radford also sought to best use the assets of businessmen and professionals who had volunteered for military service, establishing the Aviation Indoctrination School and Air Combat Intelligence School at Naval Air Station Quonset Point so as to enable these advanced recruits to become more experienced naval officers.[11]

Sea duty

[edit]

By early 1943, with Radford's training programs established and functioning efficiently, he sought combat duty.[12] In April of that year, he was ordered to report to the office of Commander, Naval Air Forces, Pacific Fleet where he was promoted to rear admiral and tapped to be a carrier division commander.[4] This was an unusual appointment, as most carrier division commanders were appointed only after duty commanding a capital ship. He then spent May and June 1943 on an inspection party under Gates, touring U.S. bases in the south Pacific.[12] Following this, he was assigned under Rear Admiral Frederick C. Sherman, commander of Carrier Division 2 at Pearl Harbor. Radford spent several weeks observing flight operations and carrier tactics for various ships operating out of Hawaii. He was particularly impressed with how carrier doctrine had evolved in the time since his own assignment on a carrier, and in June 1943, he was ordered to observe operations on the light aircraft carrier USS Independence, learning the unique challenges of using light carriers.[12]

On 21 July 1943, Radford was given command of Carrier Division Eleven, which consisted of the new Essex-class carrier USS Lexington as well as the light carriers USS Independence and USS Princeton. These carriers remained at Pearl Harbor through August, training and refining their operations. Radford got his first operational experience on 1 September 1943, covering a foray to Baker and Howland Islands as part of Task Force 11 under Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee. Radford commanded Princeton, USS Belleau Wood and four destroyers to act as a covering force for Lee's marines, who built an airfield on the islands.[13] After this successful operation, and at the direction of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Task Force 11 was joined by Task Force 15, with Lexington, under Rear Admiral Charles A. Pownall. The two task forces then steamed for Tarawa Atoll to strike it. On the night of 17 September, the carriers launched six strikes of fighter aircraft, dive bombers, and torpedo planes to work over the Japanese defenses.[14]

Next, Radford and his carriers took part in an air attack and cruiser bombardment of Wake Island on 5 to 6 October 1943. He shifted his flag to Lexington for the operation, which took two days. Though the effects on Japanese positions were not known, Radford and other leaders considered the operations useful for preparing their forces for the major battles to come in the Central Pacific.[15]

Major combat operations

[edit]Major operations in the Central Pacific began that November. Radford's next duty was in Operation Galvanic, a campaign into the Gilbert Islands with the objective of capturing Tarawa as well as Makin Island and Apamama Atoll. It would be one of the first times that American carriers would be operating against Japanese land-based air power in force, as U.S. Army troops and U.S. Marines fought the Japanese on the ground. For this mission, Radford's carrier division was designated Task Group 50.2, the Northern Carrier Group, which consisted of USS Enterprise, USS Belleau Wood and USS Monterey. He did not agree with this strategy, maintaining until his death that the force should have gone on an offensive to strike Japanese air power instead of being tied to the ground forces. Despite his objections, the force left Pearl Harbor for the Gilbert Islands on 10 November.[16]

The invasion began on 20 November. Radford's force was occupied with air strikes on Japanese ground targets, and faced frequent attack by Japanese aircraft in night combat, which U.S. aircrews were not well prepared or equipped for.[17] He improvised a unit to counter Japanese night raids, and was later credited with establishing routines for nighttime combat air patrols to protect carriers; these were adopted fleetwide.[18] He commanded Carrier Division Eleven around Tarawa for several more days, returning to Pearl Harbor on 4 December.[17]

Returning from Tarawa, Radford was reassigned as chief of staff to Towers, who was Commander, Air Force, Pacific Fleet. He assisted in planning upcoming operations, including Operation Flintlock, the invasion of the Marshall Islands. He had hoped to return to combat duty at the end of this assignment, but in March 1944 he was ordered to Washington, D.C., and appointed as Deputy Chief of Naval Operations. He assumed this new duty on 1 April, a role which was primarily administrative in nature.[17] His duties included establishing a new integrated system for aircraft maintenance, supply, and retirement, for which he was appointed the head of a board to study aircraft wear and tear. After six months in this duty, Radford was returned to the Pacific theater by Admiral Ernest J. King, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and Commander in Chief, United States Fleet.[19]

Radford returned to Pearl Harbor on 7 October 1944, where he was appointed as commander of First Carrier Task Force, Carrier Division Six. While flying to his new command, he was held over in Kwajalein and then Saipan, missing the Battle of Leyte Gulf which took place in the Philippines during the layover. He flew to Ulithi where he reported to Vice Admiral John S. McCain, Sr., commander of Task Force 58. For the next two months, Radford remained on "make learn" status, again under Sherman's command, observing the operations and employment of carrier-based air power as a passenger aboard USS Ticonderoga, part of Task Group 38.3.[19] During this time, he observed the strikes on Luzon and the Visayas, as well as air attacks on Japanese shipping and Typhoon Cobra.[20]

"To every officer and man in this splendid group well done [.] In the last 45 days you have contributed much toward the victory announced today and I am proud of you."

—Radford's message to his fleet at the end of World War II.[21]

On 29 December 1944, Radford was unexpectedly ordered to take command of Task Group 38.1 after its commander, Rear Admiral Alfred E. Montgomery, was injured. The next day the fleet sortied from Ulithi and headed for scheduled air strikes on Luzon and Formosa (Taiwan). Throughout January 1945, Radford's fleet operated in the South China Sea striking Japanese targets in French Indochina and Hong Kong. In February, the U.S. Third Fleet was re-designated the U.S. Fifth Fleet, and as a part of this reorganization Radford's force was redesignated Task Group 58.4. He continued striking Japanese targets in the Inland Sea during March. On 1 April, the force was moved to support the Battle of Okinawa. Over the course of the next two months, his force continued its use of night raids, which by this point were effective in repelling Japanese attacks on U.S. Navy ships. After two months supporting ground forces on Okinawa, Radford's fleet was detached from that operation.[21]

Returning to the Third Fleet and being re-designated Task Group 38.4, the force began operating off the Japanese Home Islands in July 1945. It began an intense airstrike campaign against military targets on Honshu and Hokkaido, striking Japanese airfields, merchant shipping, and ground targets. Radford commanded the force in this duty until V-J Day, the end of the war in the Pacific. Upon receipt of the orders to end hostilities, he signaled his ships that he was proud of their accomplishments.[21]

Post-war years

[edit]Radford was promoted to vice admiral in late 1945.[4] For a time he was Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Air under Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal.[9] During the post-war period, Radford was a strong advocate that naval aviation programs be maintained. When Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King issued a post-war plan calling for the U.S. to maintain nine active aircraft carriers, Radford suggested he double the number, a politically unrealistic proposal.[22]

After the war, Radford was a principal opponent to a plan to merge the uniformed services. A plan existed to split the Army and the Army Air Forces into separate branches and unite them and the Navy under one Cabinet-level defense organization. Fearing the loss of their branch's influence, Navy commanders opposed the formation of a separate Air Force and favored a more loose defense organization. Radford was picked by Forrestal to form the Secretary's Committee of Research and Reorganization. Months of discussion resulted in the National Security Act of 1947, a political victory for the Navy because it created the U.S. Air Force while resulting in a coordinated, not unified, U.S. Department of Defense with limited power and with the Navy maintaining control of its air assets.[9] In 1947, Radford was briefly appointed commander of the Second Task Fleet, a move he felt was to distance him from the budget negotiations in Washington, but nonetheless preferred.[23]

In 1948, Radford was appointed by President Harry S. Truman as the Vice Chief of Naval Operations (VCNO).[24] Debates continued with military leaders about the future of the United States Armed Forces as Truman sought to trim the defense budget. Radford was relied on by Navy leaders as an expert who would fiercely defend the Navy's interests from budget restrictions,[25][9] but his appointment as VCNO was opposed by Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, who feared his hard-line stance on the budget would alienate the generals in the other branches of the military.[26] Some historians contend Radford brought strong leadership to the role.[27] Naval aviation assets grew from 2,467 aircraft to 3,467 during this time, almost all aircraft for fast-attack carriers. He also oversaw the implementation of the "Full Air Program" which envisioned 14,500 total aircraft in the naval air force.[28] Along with his predecessor John Dale Price, he favored reducing naval ship strength in order to develop stronger naval aviation capabilities.[29] Then, in 1949, Truman appointed him as the High Commissioner of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.[25]

Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet

[edit]In April 1949, Truman appointed Radford to the position of Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. A staunch anticommunist, Radford saw the greatest threat to U.S. security coming from Asia, not Europe.[4] He traveled extensively throughout the Pacific as well as South Asia and the Far East. He became acquainted with political and military leaders in New Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Thailand, Malaya, Burma, India, Pakistan, Hong Kong, Formosa, and Japan, and learned about the sociopolitical issues facing each nation and the region as a whole.[30]

"Revolt of the Admirals"

[edit]Despite his new office, Radford was soon recalled to Washington to continue hearings on the future of the U.S. military budget.[31] He became a key figure in what would later be called the "Revolt of the Admirals", which took place during April 1949 when the supercarrier USS United States was cancelled.[4]

At the request of Congressman Carl Vinson, Radford strongly opposed plans by Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson and Secretary of the Navy Francis P. Matthews to make the Convair B-36 the Air Force's principal bomber aircraft, calling it a "billion dollar blunder." Radford also questioned the Air Force's plan to focus on nuclear weapons delivery capabilities as its primary deterrent to war and called nuclear war "morally reprehensible".[31] While the United States remained cancelled and the post-war cuts to the Navy were intact, funding was increasing during the Cold War era for conventional forces.[30]

Korean War

[edit]

Shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, control of Vice Admiral Arthur D. Struble's U.S. Seventh Fleet was transferred from Radford to Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy, who was serving as Commander, Naval Forces, Far East.[32] Joy's superior was General of the Army Douglas MacArthur of the United Nations Command Korea (UNC). As such, Radford exercised no direct responsibility over forces involved in the conflict.[33]

Radford was an admirer of MacArthur and a proponent of his "Asia First" strategy.[33] He supported Operation Chromite in October 1950,[34][35] as well as the United Nations mission of Korean reunification. He attended the Wake Island Conference between MacArthur and Truman on 15 October, and later recalled his belief that, should the Chinese intervene in the war, the U.S. could still prevail provided it was able to strike Chinese People's Liberation Army bases in Manchuria with air power. When the People's Volunteer Army did intervene in favor of North Korea the next month, Radford shared MacArthur's frustration at restrictions placed on the UN force in the war preventing it from striking Chinese soil. Once Truman relieved MacArthur in April 1951, Radford reportedly gave the general a "hero's welcome" in Hawaii as he was returning to the United States.[33]

As commander of U.S. forces in the Philippines and Formosa, Radford accompanied President-elect Dwight D. Eisenhower on his three-day trip to Korea in December 1952.[36] Eisenhower was looking for an exit strategy for the stalemated and unpopular war, and Radford suggested threatening China with attacks on its Manchurian bases and the use of nuclear weapons.[33] This view was shared by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and UNC Commanding General Mark W. Clark, but had not been acted on when the armistice came in July 1953, at a time when the Chinese were struggling with domestic unrest.[37] Still, Radford's frankness during the trip and his knowledge of Asia made a good impression on Eisenhower, who nominated Radford to be his Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[33][38]

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

[edit]"I simply must find men who have the breadth of understanding and devotion to the country rather than to a single Service that will bring about better solutions than I get now. ... [strangely] enough the one man who sees this clearly is a Navy man who at one time was an uncompromising exponent of naval power and its superiority over any other kind of strength. That is Radford."

—Eisenhower on his choice to nominate Radford as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[3]

Eisenhower's official nomination for Radford came in mid-1953. Eisenhower was initially cautious about him because of his involvement in the inter-service rivalry and "revolt" in 1949. Radford's anticommunist views, however, as well as his knowledge of Asia and his support of Eisenhower's "New Look" defense policy, made him an attractive nominee, particularly among Republicans, to replace Omar Bradley.[39] Eisenhower was also impressed with his "intelligence, dedication, tenacity, and courage to speak his mind."[40] During his nomination, Radford indicated a changed outlook from the positions he had taken during the "Revolt of the Admirals".[30] As chairman, he was eventually popular with both the president and Congress.[41]

Military budget

[edit]

Radford was integral in formulating and executing the "New Look" policy, reducing spending on conventional military forces to favor a strong nuclear deterrent and a greater reliance on airpower.[39] In this time, he had to overcome resistance from Army leaders who opposed the reduction of their forces, and Radford's decisions, unfettered by inter-service rivalry, impressed Eisenhower.[3] In spite of his support of the "New Look", he disagreed with Eisenhower on several occasions when the president proposed drastic funding cuts that Radford worried would render the U.S. Navy ineffective.[18] In late 1954, for example, Radford testified privately before a congressional committee that he felt some of Eisenhower's proposed defense cuts would limit the military's capability for "massive retaliation", but he kept his disagreements out of public view, working from within and seeking the funding to save specific strategic programs.[42]

In 1956, Radford proposed protecting several military programs from funding cuts by reducing numbers of conventional forces, but the proposal was leaked to the press, causing an uproar in Congress and among U.S. military allies, and the plan was dropped. In 1957, after the other Joint Chiefs of Staff again disagreed on how to downsize force levels amid more budget restrictions, Radford submitted ideas for less dramatic force downsizing directly to Secretary of Defense Charles Erwin Wilson, who agreed to pass them along to Eisenhower.[42]

Foreign military policy

[edit]While Radford remained Eisenhower's principal adviser for the budget, they differed on matters of foreign policy.[42] Radford advocated the use of nuclear weapons and a firm military and diplomatic stance against China.[18] Early in his tenure, he suggested to Eisenhower a preventive war against China or the Soviet Union while the U.S. possessed a nuclear advantage and before it became entangled in conflicts in the Far East. Eisenhower immediately dismissed this idea.[42]

After France requested U.S. assistance for its beleaguered force at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, Radford suggested an aggressive stance toward the Viet Minh by promoting Operation Vulture in which 60 U.S. Air Force B-29 Superfortress bombers would conduct airstrikes on Viet Minh positions.[43] Radford even believed in the U.S. threaten it with nuclear weapons, like earlier with the Chinese in Korea.[33] He also advocated U.S. military intervention in the 1955 First Taiwan Strait Crisis and the 1956 Suez Crisis, but Eisenhower favored diplomatic approaches and threats of force.[42]

Later life

[edit]

After his second term as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Radford opted to retire from the Navy in 1957 to enter the private sector. The same year Radford High School in Honolulu was named in his honor. Radford was called upon to serve as military campaign advisor for Richard Nixon in the 1960 presidential election, and again for Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election.[33]

Radford died of cancer at age 77 on 17 August 1973[33] at Bethesda Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. He is buried with his wife Miriam J. Radford (1895–1997) at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.[44][18] In 1975, the Navy launched the anti-submarine Spruance-class destroyer USS Arthur W. Radford, named in his honor.[18]

Dates of rank

[edit] United States Naval Academy Midshipman – Class of 1916

United States Naval Academy Midshipman – Class of 1916

| Ensign | Lieutenant (junior grade) | Lieutenant | Lieutenant Commander | Commander | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-1 | O-2 | O-3 | O-4 | O-5 | O-6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 3 June 1916 | 1 July 1917 | 1 January 1918 | 17 February 1927 | 1 July 1936 | 1 January 1942 |

| Rear Admiral (lower half) | Rear Admiral (upper half) | Vice Admiral | Admiral |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-7 | O-8 | O-9 | O-10 |

|

|

|

|

| Never held | 21 July 1943 | 25 May 1946 | 7 April 1949 |

Awards and decorations

[edit]Radford's awards and decorations include the following:[46]

| ||

| Naval Aviator Badge | ||

| Navy Distinguished Service Medal with three stars |

Legion of Merit with star |

Navy Presidential Unit Citation with two service stars |

| Navy Unit Commendation | World War I Victory Medal with service star |

American Defense Service Medal with service star |

| American Campaign Medal | Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with seven battle stars |

World War II Victory Medal |

| Navy Occupation Medal | National Defense Service Medal | Korean Service Medal |

| Order of Fiji | Companion of the Order of the Bath | Philippine Liberation Medal with service star |

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Muir 2001, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Muir 2001, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tucker 2009, p. 725.

- ^ a b c d Stewart 2009, p. 242.

- ^ Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 109.

- ^ 1900 U.S. Census – Census Place: Portland Ward 6, Multnomah, Oregon; Roll: 1350; Page: 11B; Enumeration District: 0063; FHL microfilm: 1241350

- ^ a b c Muir 2001, p. 161.

- ^ a b c d Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 110.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 162.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 163.

- ^ a b c Muir 2001, p. 164.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 165.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 166.

- ^ Muir 2001, pp. 166–67.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 167.

- ^ a b c Muir 2001, p. 168.

- ^ a b c d e Stewart 2009, p. 243.

- ^ a b Muir 2001, p. 169.

- ^ Muir 2001, p. 170.

- ^ a b c Muir 2001, p. 171.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 14.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 41.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 44.

- ^ a b Palmer 1990, p. 40.

- ^ Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 114.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 47.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 52.

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 112.

- ^ a b Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 111.

- ^ James & Wells 1992, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Tucker 2009, p. 726.

- ^ Tucker 2009, p. 683.

- ^ James & Wells 1992, p. 87.

- ^ Bowie & Immerman 2000, p. 84.

- ^ Tucker 2009, p. 670.

- ^ James & Wells 1992, p. 119.

- ^ a b Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 107.

- ^ Bowie & Immerman 2000, p. 182.

- ^ Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 113.

- ^ Hastings, Max (2018). Vietnam : an Epic Tragedy, 1945-1975 (First ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-0-06-240566-1. OCLC 1001744417.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Burial Detail: Radford, Arthur W (Section 30, Grave 435-LH – ANC Explorer

- ^ The Chairmanship of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1949-2012 (PDF) (2 ed.). Joint History Office. 27 October 2012. p. 89. ISBN 978-1480200203.

- ^ Hattendorf & Elleman 2010, p. 106.

Sources

[edit]- Bowie, Robert R.; Immerman, Richard H. (2000), Waging Peace: How Eisenhower Shaped an Enduring Cold War Strategy, New York City: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-514048-4

- Hattendorf, John B.; Elleman, Bruce A. (2010), Nineteen-Gun Salute: Case Studies of Operational, Strategic, and Diplomatic Naval Leadership During the 20th and Early 21st Centuries, Washington, D.C.: Department of the Navy, ISBN 978-1-884733-66-6

- James, D. Clayton; Wells, Anne Sharp (1992), Refighting the Last War: Command and Crisis in Korea 1950–1953, New York City: Free Press, ISBN 978-0-02-916001-5

- Muir, Malcolm Jr. (2001), The Human Tradition in the World War II Era, Lanham, Maryland: SR Books, ISBN 978-0-8420-2786-1

- Palmer, Michael A. (1990), Origins of the Maritime Strategy: The Development of American Naval Strategy, 1945–1955, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-0-87021-667-1

- Stewart, William (2009), Admirals of the World: A Biographical Dictionary, 1500 to the Present, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, ISBN 978-0-7864-3809-9

- Tucker, Spencer (2009), U.S. Leadership in Wartime: Clashes, Controversy, and Compromise, Volume 1, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-172-5

- Lowrey, Nathan S. (2016), The Chairmanship of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1949-2016, Joint History Office, ISBN 978-1075301711

Further reading

[edit]- Radford, Arthur W.; Jurika, Stephen (1980). From Pearl Harbor to Vietnam: the memoirs of Admiral Arthur W. Radford. Palo Alto, California: Hoover Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-7211-0.

External links

[edit]- Arthur W. Radford, Dictionary of Naval Fighting Ships, Naval Historical Center, Department of the Navy.

- Arthur W. Radford Scrapbook, 1910–1975 (bulk 1912–1913), MS 502 held by Special Collections & Archives, Nimitz Library at the United States Naval Academy

- 1896 births

- 1973 deaths

- American anti-communists

- United States Navy personnel of World War I

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

- High commissioners of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands

- Honorary companions of the Order of the Bath

- Military personnel from Chicago

- Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- United States Naval Academy alumni

- United States Naval Aviators

- United States Navy admirals

- Vice chiefs of Naval Operations

- United States Navy World War II admirals

- WAVES (Navy)