Siege of Baghdad

| Battle of Baghdad | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasions | |||||||

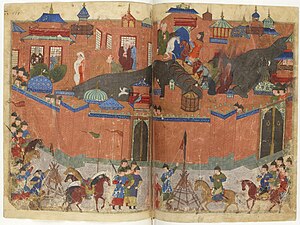

Hulagu's army attacks Baghdad. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Mongol Empire Armeno-Mongol alliance | Abbasid Caliphate | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hulagu Khan Guo Kan Baiju Kitbuga Koke Ilge | Caliph Al-Musta'sim | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

120,000[1]-150,000[2] total (40,000 Armenian infantry, 12,000 Armenian cavalry, and Mongol, Turkish, Persian and Georgian soldiers)[1][2] | 50,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown but believed to be minimal |

50,000 soldiers, 90,000-1,000,000 civilians | ||||||

The Battle of Baghdad in 1258 was a victory for the Mongol leader Hulagu Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan. Baghdad was captured, sacked, and burned.

Background

Baghdad was the capital of the Abbasid caliphate, an Islamic state in what is now Iraq, ruled by Al-Musta'sim, the Abbasid caliph. The Abbasid caliphs were the second of the Islamic dynasties, having defeated the Umayyads, who had ruled from the death of Ali in 661 until 751, when the first Abbasid acceded the throne [3]. At Baghdad's peak it had a population of approximately one million residents, and an army that was 60,000 strong, though its power and influence had decreased by the mid-1200s. Once mighty, the Abbasids had lost control over much of the former Islamic empire and declined into a minor state. However, although the caliph was a figurehead, controlled by Mamluk or Turkic warlords, he still had great symbolic significance, and Baghdad was still a rich and cultured city.

Composition of the besieging army

The Mongol army, led by Hulagu (also spelled as Hulegu) Khan and the Chinese commander Guo Kan in vice-command, set out for Baghdad in November of 1257. Hulagu marched with what was probably the largest army ever fielded by the Mongols. By order of Mongke Khan, one in ten fighting men in the entire empire were gathered for Hulagu's army (Saunders 1971). The attacking army also had a large contingent of Christian forces. The main Christian force seems to have been the Georgians, who took a very active role in the destruction.[4]. According to Alain Demurger, Frankish troops from the Principality of Antioch also participated.[5] Also, Ata al-Mulk Juvayni describes about 1000 Chinese artillery experts, and Armenians, Georgians, Persian and Turks as participants in the Siege.[2]

The siege

Hulagu demanded surrender; the caliph refused, warning the Mongols that they faced the wrath of Allah if they attacked the caliph. Many accounts say that the caliph failed to prepare for the onslaught; he neither gathered armies nor strengthened the walls of Baghdad. David Nicolle states flatly that the Caliph not only failed to prepare, even worse, he greatly offended Hulagu Khan by his threats, and thus assured his destruction. (Monke Khan had ordered his brother to spare the Caliphate if it submitted to the authority of the Mongol Khanate.)

Prior to laying siege to Baghdad, Hulagu easily destroyed the Lurs, and his reputation so frightened the Assassins (also known as the Hashshashin) that they surrendered their impregnable fortress of Alamut to him without a fight in 1256. He then advanced on Baghdad.

Once near the city, Hulagu divided his forces, so that they threatened both sides of the city, on the east and west banks of the Tigris. The caliph's army repulsed some of the forces attacking from the west, but were defeated in the next battle. The attacking Mongols broke some dikes and flooded the ground behind the caliph’s army, trapping them. Much of the army was slaughtered or drowned.

Under Guo Kan's order, the Chinese counterparts in the Mongolian army then laid siege to the city, constructing a palisade and ditch, wheeling up siege engines and catapults. The siege started on January 29. The battle was swift, by siege standards. By February 5 the Mongols controlled a stretch of the wall. Al-Musta'sim tried to negotiate, but was refused.

On February 10 Baghdad surrendered. The Mongols swept into the city on February 13 and began a week of massacre, looting, rape, and destruction.

Destruction of Baghdad

Many historical accounts detailed the cruelties of the Mongol conquerors.

- The Grand Library of Baghdad, containing countless precious historical documents and books on subjects ranging from medicine to astronomy, was destroyed. Survivors said that the waters of the Tigris ran black with ink from the enormous quantities of books flung into the river.

- Citizens attempted to flee, but were intercepted by Mongol soldiers who killed with abandon. Martin Sicker writes that close to 90,000 people may have died (Sicker 2000, p. 111). Other estimates go much higher. Wassaf claims the loss of life was several hundred thousand. Ian Frazier of The New Yorker says estimates of the death toll have ranged from 200,000 to a million.[6]

- The Mongols looted and then destroyed mosques, palaces, libraries, and hospitals. Grand buildings that had been the work of generations were burned to the ground.

- The caliph was captured and forced to watch as his citizens were murdered and his treasury plundered. According to most accounts, the caliph was killed by trampling. The Mongols rolled the caliph up in a rug, and rode their horses over him, as they believed that the earth was offended if touched by royal blood. All but one of his sons were killed, and the sole surviving son was sent to Mongolia. (see Abbasid: The end of the dynasty)

- Hulagu had to move his camp upwind of the city, due to the stench of decay from the ruined city.

Typically, the Mongols destroyed a city only if it had resisted them. Cities that capitulated at the first demand for surrender could usually expect to be spared. The destruction of Baghdad was to some extent a military tactic: it was supposed to convince other cities and rulers to surrender without a fight, and while that worked with Damascus, it failed with Mamluk Egypt, which was inspired to resist, and subsequently defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260 - a battle that saw the first real unavenged defeat of the Mongol Empire.

Baghdad was a depopulated, ruined city for several centuries and only gradually recovered some of its former glory.

Comments on the destruction

- "Iraq in 1258 was very different from present day Iraq. Its agriculture was supported by canal networks thousands of years old. Baghdad was one of the most brilliant intellectual centers in the world. The Mongol destruction of Baghdad was a psychological blow from which Islam never recovered. Already Islam was turning inward, becoming more suspicious of conflicts between faith and reason and more conservative. With the sack of Baghdad, the intellectual flowering of Islam was snuffed out. Imagining the Athens of Pericles and Aristotle obliterated by a nuclear weapon begins to suggest the enormity of the blow. The Mongols filled in the irrigation canals and left Iraq too depopulated to restore them." (Steven Dutch)

- "They swept through the city like hungry falcons attacking a flight of doves, or like raging wolves attacking sheep, with loose reins and shameless faces, murdering and spreading terror...beds and cushions made of gold and encrusted with jewels were cut to pieces with knives and torn to shreds. Those hiding behind the veils of the great Harem were dragged...through the streets and alleys, each of them becoming a plaything...as the population died at the hands of the invaders." (Abdullah Wassaf as cited by David Morgan)

Destruction or salination?

Some historians believe that the Mongol invasion destroyed much of the irrigation infrastructure that had sustained Mesopotamia for many millennia. Canals were cut as a military tactic and never repaired. So many people died or fled that neither the labor nor the organization were sufficient to maintain the canal system. It broke down or silted up. This theory was advanced by historian Svatopluk Souček in his 2000 book, A History of Inner Asia and has been adopted by authors such as Steven Dutch.

Other historians point to soil salination as the culprit in the decline in agriculture. [1] [2]

Complicity of the Shi'a?

One author, Reuvan Amitai-Preiss, has alleged that the Mongols were aided by Shi'a Muslims who bore a grudge against the Sunni Abbasids. But another, David Nicolle, alleged that most of the Shi'a who joined the invaders did so out of fear of being slaughtered, as all those who resisted were being killed. Any force that surrendered at once, as had virtually all of southern Persia and what is today northern Iraq, were allowed to live but, as Mongol vassals, had to provide troops for the invaders. Later, as Il-Khan, Hulagu, in organizing his domains, integrated these troops into his army more thoroughly, though the vast majority of his troops were Mongols -- one Mongol in ten had been drafted for his army -- and Turkic nomads who had submitted to the Mongols.

Aftermath

The year following the fall of Baghdad, Hulagu named the Persian Ata al-Mulk Juvayni governor of Baghdad, Lower Mesopotamia, and Khuzistan. At the intervention of the Mongol Hulagu's Nestorian Christian wife Dokuz Khatun, the Christian inhabitants were spared.[7][8] Hulagu offered the royal palace to the Nestorian Catholicus Mar Makikha, and ordered a cathedral to be built for him.[9]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b L. Venegoni (2003). Hülägü's Campaign in the West - (1256-1260), Transoxiana Webfestschrift Series I, Webfestschrift Marshak 2003.

- ^ a b c In the National Geographic, University of Michigan, original issue, v.191, 1997: "In 1253, the Persian writer Ala-ad-Din Ata-Malik Juvaini recorded Hulagu's preparations for his Baghdad expedition. With the cavalry were a thousand expert artillerymen from China. The army swelled with troops from vassal states: Armenians, Georgians, Persians, Turks. By one estimate, the force grew to 150,000 men."

- ^ Nicolle, p. 108

- ^ In The Fire, the Star and the Cross. by Aptin Khanbaghi (p.60): During the siege of Baghdad "the Mongol army included a large Christian contingent, mainly Georgians. The Mongols did not have to beg for their assistance, as the Georgians had suffered tremendously from the cruelty of the Muslims during the invasion of Jalal al-Din Khwarazmshah a few decades earlier. Their churches had been razed and the population of Tiflis massacred. During the sack of Baghdad, the Mongols gave the Georgians a chance to take their revenge on the Muslims."

- ^ In Demurger Les Templiers (p.80-81): "The main adversary of the Mongols in the Middle-East was the Mamluk Sultanate and the Califate of Baghdad; in 1258 they take the city, sack it, massacre the population and exterminate the Abassid familly who ruled the Califate since 750; the king of Little Armenia (of Cilicia) and the troops of Antioch participated in the fight and the looting together with the Mongols." In Demurger Croisades et Croisés au Moyen-Age (p.284): "The Franks of Tripoli and Antioch, just as the Armenians of Cilicia who since the submission of Asia Minor in 1243 had to recognize Mongol overlordship and pay tribute, participated to the capture of Baghdad."

- ^ Ian Frazier, Annals of history: Invaders: Destroying Baghdad, The New Yorker 25 April 2005. p.4

- ^ Maalouf, p. 243

- ^ "A history of the Crusades", Steven Runciman, p.306

- ^ Foltz, p.123

References

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven. Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281 (first edition). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-46226-6.

- Morgan, David. The Mongols. Boston: Blackwell Publishing, 1990. ISBN 0-631-17563-6.

- Nicolle, David, and Richard Hook (illustrator). The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane. London: Brockhampton Press, 1998. ISBN 1-86019-407-9.

- Saunders, J.J. The History of the Mongol Conquests. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8122-1766-7.

- Sicker, Martin. The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0-275-96892-8.

- Souček, Svat. A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-521-65704-0.

External links

- An article describing Hulagu's conquest of Baghdad, written by Ian Frazier, appeared in the April 25, 2005 issue of The New Yorker.

- Steven Dutch article