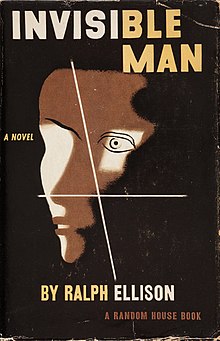

Invisible Man

Front dust jacket art of the first edition | |

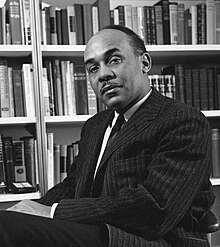

| Author | Ralph Ellison |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Edward McKnight Kauffer |

| Language | English |

| Genre | |

| Publisher | Random House |

Publication date | April 14, 1952[1] |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover and paperback) |

| Pages | 581 (second edition) |

| ISBN | 978-0-679-60139-5 |

| OCLC | 30780333 |

| 813/.54 20 | |

| LC Class | PS3555.L625 I5 1994 |

Invisible Man is Ralph Ellison's first novel, the only one published during his lifetime. It was published by Random House in 1952, and addresses many of the social and intellectual issues faced by African Americans in the early 20th century, including black nationalism, the relationship between black identity and Marxism, and the reformist racial policies of Booker T. Washington, as well as issues of individuality and personal identity.

Invisible Man won the U.S. National Book Award for Fiction in 1953, making Ellison the first African-American writer to win the award.[2] In 1998, the Modern Library ranked Invisible Man 19th on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century.[3] Time magazine included the novel in its 100 Best English-language novels from 1923 to 2005 list, calling it "the quintessential American picaresque of the 20th century", rather than a "race novel, or even a bildungsroman".[4] Malcolm Bradbury and Richard Ruland recognize a black existentialist vision with a "Kafka-like absurdity".[5] According to The New York Times, Barack Obama modeled his 1995 memoir Dreams from My Father on Ellison's novel.[6]

Background

[edit]Ellison says in his introduction to the 30th Anniversary Edition that he started to write what would eventually become Invisible Man in a barn in Waitsfield, Vermont (actually in the neighboring town of Fayston[7]), in the summer of 1945 while on sick leave from the Merchant Marine.[8] The book took five years to complete with one year off for what Ellison termed an "ill-conceived short novel".[9] Invisible Man was published as a whole in 1952. Ellison had published a section of the book in 1947, the famous "Battle Royal" scene, which had been shown to Cyril Connolly, the editor of Horizon magazine by Frank Taylor, one of Ellison's early supporters.

In his speech accepting the 1953 National Book Award, Ellison said that he considered the novel's chief significance to be its "experimental attitude."[10] Before Invisible Man, many (if not most) novels dealing with African Americans were written solely for social protest, notably, Native Son and Uncle Tom's Cabin. The narrator in Invisible Man says, "I am not complaining, nor am I protesting either", signaling a break from the usual protest novel. In the essay "The World and the Jug," a response to Irving Howe's essay "Black Boys and Native Sons" which "pit[s] Ellison and [James] Baldwin against [Richard] Wright and then", as Ellison would say, "gives Wright the better argument," Ellison makes a fuller statement about the position he held about his book in the larger canon of work by an American who happens to be of African ancestry. In the opening paragraph to that essay Ellison poses three questions: "Why is it so often true that when critics confront the American as Negro they suddenly drop their advanced critical armament and revert with an air of confident superiority to quite primitive modes of analysis? Why is it that Sociology-oriented critics seem to rate literature so far below politics and ideology that they would rather kill a novel than modify their presumptions concerning a given reality which it seeks in its own terms to project? Finally, why is it that so many of those who would tell us the meaning of Negro life never bother to learn how varied it really is?"[citation needed]

Placing Invisible Man within the canon of either the Harlem Renaissance or the Black Arts Movement is difficult. It owes allegiance to both and neither. Ellison's resistance to being pigeonholed by his peers bubbled over into his statement to Irving Howe about what he deemed to be a relative vs. an ancestor. He says to Howe "...perhaps you will understand when I say that he [Wright] did not influence me if I point out that while one can do nothing about choosing one's relatives, one can, as an artist, choose one's 'ancestors'. Wright was, in this sense, a 'relative'; Hemingway an 'ancestor'." It was this idea of "playing the field," so to speak, not being "all-in", that led to some of Ellison's more staunch critics. Howe, in "Black Boys and Native Sons", but also other black writers such as John Oliver Killens, who once denounced Invisible Man by saying: "The Negro people need Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man like we need a hole in the head or a stab in the back. ... It is a vicious distortion of Negro life."[citation needed]

Ellison's "ancestors" included, among others, T. S. Eliot. In an interview with Richard Kostelanetz, Ellison states that what he had learned from his The Waste Land was imagery and also improvisation techniques he had only before seen in jazz.[11] Some other influences include William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway. Ellison once called Faulkner the South's greatest artist, and in the Spring 1955 Paris Review, Ellison said of Hemingway: "I read him to learn his sentence structure and how to organize a story. I guess many young writers were doing this, but I also used his description of hunting when I went into the fields the next day. I had been hunting since I was eleven, but no one had broken down the process of wing-shooting for me, and it was from reading Hemingway that I learned to lead a bird. When he describes something in print, believe him; believe him even when he describes the process of art in terms of baseball or boxing; he’s been there."[9]

Some of Ellison's influences had a more direct impact on his novel. The first line of Invisible Man ("I am an invisible man") for example, is a conscious echo of Notes from Underground ("I am a sick man").[12] Ellison acknowledged this borrowing in his 1981 introduction to his novel saying the novel's main character can be "associated, ever so distantly, with the narrator of Dostoevsky's Notes From Underground".[13]

Arnold Rampersad, Ellison's biographer, says that Herman Melville had a profound influence on Ellison's way of writing about race: the narrator "resembles no one else in previous fiction so much as he resembles Ishmael of Moby-Dick".[citation needed] Ellison signals his debt in the prologue to the novel, where the narrator remembers a moment of truth under the influence of marijuana and evokes a church service: "Brothers and sisters, my text this morning is the 'Blackness of Blackness'. And the congregation answers: 'That blackness is most black, brother, most black...'" In this scene Ellison "reprises a moment in the second chapter of Moby-Dick", where Ishmael wanders around New Bedford looking for a place to spend the night and enters a black church: "It was a negro church; and the preacher's text was about the blackness of darkness, and the weeping and wailing and teeth-gnashing there." According to Rampersad, it was Melville who "empowered Ellison to insist on a place in the American literary tradition" by his example of "representing the complexity of race and racism so acutely and generously" in Moby-Dick.[citation needed]

Political influences and the Communist Party

[edit]The letters he wrote to fellow novelist Richard Wright as he started working on the novel provide evidence for his disillusion with and defection from the Communist Party USA for perceived revisionism. In a letter to Wright on August 18, 1945, Ellison poured out his anger toward party leaders for betraying African-American and Marxist class politics during the war years: "If they want to play ball with the bourgeoisie they needn't think they can get away with it... Maybe we can't smash the atom, but we can, with a few well-chosen, well-written words, smash all that crummy filth to hell."[14] Ellison resisted attempts to ferret out such allusions in the book itself however, stating "I did not want to describe an existing Socialist or Communist or Marxist political group, primarily because it would have allowed the reader to escape confronting certain political patterns, patterns which still exist and of which our two major political parties are guilty in their relationships to Negro Americans."[15]

Plot summary

[edit]The narrator, an unnamed black man, begins by describing his living conditions: an underground room wired with hundreds of electric lights, operated by power stolen from the city's electric grid. He reflects on the various ways in which he has experienced social invisibility during his life and begins to tell his story, returning to his teenage years.

The narrator lives in a small Southern town and, upon graduating from high school, wins a scholarship to an all-black college after taking part in a brutal, humiliating battle royal for the entertainment of the town's rich white dignitaries.

One afternoon during his junior year at the college, the narrator chauffeurs Mr. Norton, a visiting rich white trustee, out among the old slave-quarters beyond the campus. By chance, he stops at the cabin of Jim Trueblood, who has caused a scandal by impregnating both his wife and his daughter in his sleep. Trueblood's account horrifies Mr. Norton so badly that he asks the narrator to find him a drink. The narrator drives him to a bar filled with prostitutes and patients from a nearby mental hospital. The mental patients rail against both of them and eventually overwhelm the orderly assigned to keep the patients under control, injuring Mr. Norton in the process. The narrator hurries Mr. Norton away from the chaotic scene and back to campus.

Dr. Bledsoe, the college president, excoriates the narrator for showing Mr. Norton the underside of black life beyond the campus and expels him. However, Bledsoe gives several sealed letters of recommendation to the narrator, to be delivered to friends of the college in order to assist him in finding a job so that he may eventually earn enough to re-enroll. The narrator travels to New York and distributes his letters, with no success; the son of one recipient shows him the letter, which reveals Bledsoe's intent never to admit the narrator as a student again.

Acting on the son's suggestion, the narrator seeks work at the Liberty Paint factory, renowned for its pure white paint. He is assigned first to the shipping department, then to the boiler room, whose chief attendant, Lucius Brockway, is highly paranoid and suspects that the narrator is trying to take his job. This distrust worsens after the narrator stumbles into a union meeting, and Brockway attacks the narrator and tricks him into setting off an explosion in the boiler room. The narrator is hospitalized and subjected to shock treatment, overhearing the doctors' discussion of him as a possible mental patient.

After leaving the hospital, the narrator faints on the streets of Harlem and is taken in by Mary Rambo, a kindly old-fashioned woman who reminds him of his relatives in the South. He later happens across the eviction of an elderly black couple and makes an impassioned speech that incites the crowd to attack the law enforcement officials in charge of the proceedings. The narrator escapes over the rooftops and is confronted by Brother Jack, the leader of a group known as "the Brotherhood" that professes its commitment to bettering conditions in Harlem and the rest of the world. At Jack's urging, the narrator agrees to join and speak at rallies to spread the word among the black community. Using his new salary, he pays Mary back the rent he owes her and moves into an apartment provided by the Brotherhood.

The rallies go smoothly at first, with the narrator receiving extensive indoctrination on the Brotherhood's ideology and methods. Soon, though, he encounters trouble from Ras the Exhorter, a fanatical black nationalist who believes that the Brotherhood is controlled by whites. Neither the narrator nor Tod Clifton, a youth leader within the Brotherhood, is particularly swayed by his words. The narrator is later called before a meeting of the Brotherhood and accused of putting his own ambitions ahead of the group. He is reassigned to another part of the city to address issues concerning women, seduced by the wife of a Brotherhood member, and eventually called back to Harlem when Clifton is reported missing and the Brotherhood's membership and influence begin to falter.

The narrator can find no trace of Clifton at first, but soon discovers him selling dancing Sambo dolls on the street, having become disillusioned with the Brotherhood. Clifton is shot and killed by a policeman while resisting arrest; at his funeral, the narrator delivers a rousing speech that rallies the crowd to support the Brotherhood again. At an emergency meeting, Jack and the other Brotherhood leaders criticize the narrator for his unscientific arguments and the narrator determines that the group has no real interest in the black community's problems.

The narrator returns to Harlem, trailed by Ras's men, and buys a hat and a pair of sunglasses to elude them. As a result, he is repeatedly mistaken for a man named Rinehart, known as a lover, a hipster, a gambler, a briber, and a spiritual leader. Understanding that Rinehart has adapted to white society at the cost of his own identity, the narrator resolves to undermine the Brotherhood by feeding them dishonest information concerning the Harlem membership and situation. After seducing the wife of one member in a fruitless attempt to learn their new activities, he discovers that riots have broken out in Harlem due to widespread unrest. He realizes that the Brotherhood has been counting on such an event in order to further its own aims. The narrator gets mixed up with a gang of looters, who burn down a tenement building, and wanders away from them to find Ras, now on horseback, armed with a spear and shield, and calling himself "the Destroyer". Ras shouts for the crowd to lynch the narrator, but the narrator attacks him with the spear and escapes into an underground coal bin. Two white men seal him in, leaving him alone to ponder the racism he has experienced in his life.

The epilogue returns to the present, with the narrator stating that he is ready to return to the world because he has spent enough time hiding from it. He explains that he has told his story in order to help people see past his own invisibility, and also to provide a voice for people with a similar plight: "Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?"

Reception

[edit]Critic Orville Prescott of The New York Times called the novel "the most impressive work of fiction by an American Negro which I have ever read", and felt it marked "the appearance of a richly talented writer".[16] Novelist Saul Bellow in his review found it "a book of the very first order, a superb book...it is tragi-comic, poetic, the tone of the very strongest sort of creative intelligence".[17] George Mayberry of The New Republic said Ellison "is a master at catching the shape, flavor and sound of the common vagaries of human character and experience".[18]

Anthony Burgess described the novel as "a masterpiece".[19]

In 2003, a sculpture titled "Invisible Man: A Memorial to Ralph Ellison" by Elizabeth Catlett, was unveiled at Riverside Park at 150th Street in Manhattan, opposite from where Ellison lived and three blocks from the Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum, where he is interred in a crypt. The 15-foot-high, 10-foot-wide bronze monolith features a hollow silhouette of a man and two granite panels that are inscribed with Ellison quotations.[20]

Adaptation

[edit]It was reported in October 2017 that streaming service Hulu was developing the novel into a television series.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Denby, David (April 12, 2012). "Justice For Ralph Ellison". The New Yorker. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ "National Book Awards – 1953". National Book Foundation. 1953. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018.

- ^ "100 Best Novels". Modern Library. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- ^ Grossman, Lev (January 7, 2010). "All-TIME 100 Novels". Time – via entertainment.time.com.

- ^ Malcolm Bradbury and Richard Ruland, From Puritanism to Postmodernism: A History of American Literature. Penguin, 380. ISBN 0-14-014435-8

- ^ Greg Grandin, "Obama, Melville, and the Tea Party". Archived November 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 18 January 2014. Retrieved on 17 March 2016.

- ^ Anna Van Dine (June 30, 2020). "How Invisible Man Was Born in a Vermont Barn". Vermont Public.

- ^ Ellison, Ralph Waldo 1982. Invisible Man. New York: Random House.

- ^ a b Alfred Chester; Vilma Howard (Spring 1955). "Ralph Ellison, The Art of Fiction". The Paris Review. No. 8. p. 113.

- ^ Herbert William Rice (2003). Ralph Ellison and the Politics of the Novel. Lexington Books. p. 107. ISBN 9780739106549.

- ^ Ellison, Ralph; Kostelanetz, Richard (October 1, 1989). "An Interview with Ralph Ellison". The Iowa Review. 19 (3): 1–10. doi:10.17077/0021-065X.3779.

- ^ Bloshteyn, Maria R. (2001). "Rage and Revolt: Dostoevsky and Three African-American Writers". Comparative Literature Studies. 38 (4): 277–309. doi:10.1353/cls.2001.0031. JSTOR 40247313.

In reply to an interviewer who suggested that [...there was] 'some correspondence between Invisible Man's Prologue and that of Moby Dick,' Ellison countered: 'Let me test something on you'—whereupon he read the opening lines from chapter one of Dostoevsky's Notes from the Underground, and concluded, chuckling, 'That ain't Melville.'

- ^ Bloshteyn, 295.

- ^ Carol Polsgrove (2001), Divided Minds: Intellectuals and the Civil Rights Movement, pp. 66–69.

- ^ Victor Moses (2003), The Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison, edited by John F. Callahan (New York: Modern Library), 542.

- ^ Prescott, Orville. "Books of the Times". The New York Times. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ Bellow, Saul (June 1952). "Man Underground". Commentary. pp. 608–610. Retrieved January 9, 2022 – via writing.upenn.edu.

- ^ Mayberry, George (September 26, 2013). "George Mayberry's 1952 Review of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man". The New Republic. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ Anthony Burgess (April 3, 2014). You've Had Your Time. Random House. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-4735-1239-9.

- ^ "NYC Parks". Archived from the original on July 23, 2021. Retrieved July 23, 2021.

- ^ Holloway, Daniel (October 26, 2017). "Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man Series Adaptation in the Works at Hulu (Exclusive)". Variety. Retrieved October 26, 2017.

External links

[edit]- "Ralph Ellison, 1914–1994: His Book Invisible Man Won Awards and Is Still Discussed Today" (VOA Special English).

- New York Times article on the 30th Anniversary of the novel's publication—includes an interview with the author.

- Teacher's Guide at Random House.

- Invisible Man, Literary Encyclopedia at the Wayback Machine (archived October 31, 2004)

- Saul Bellow's 1952 Review of Invisible Man, via Dr. Alan Filreis

- Photos of the first edition of Invisible Man, First Edition Points

- Notes on Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, GradeSaver

- 1952 American novels

- 1952 debut novels

- African-American novels

- American autobiographical novels

- Existentialist novels

- Novels set in Harlem

- National Book Award for Fiction–winning works

- Novels about race and ethnicity

- Novels by Ralph Ellison

- Random House books

- Southern United States in fiction

- American picaresque novels