Bulimia nervosa

This article needs to be updated. (September 2024) |

| Bulimia nervosa | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Bulimia |

| |

| Loss of enamel (acid erosion) from the inside of the upper front teeth as a result of bulimia | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, clinical psychology |

| Symptoms | Eating a large amount of food in a short amount of time followed by vomiting or the use of laxatives, often normal weight[1][2] |

| Complications | Breakdown of the teeth, depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, suicide[2][3] |

| Causes | Genetic and environmental factors[2][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on person's medical history[5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Anorexia, binge eating disorder, Kleine-Levin syndrome, borderline personality disorder[5] |

| Treatment | Cognitive behavioral therapy[2][6] |

| Medication | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressant[4][7] |

| Prognosis | Half recover over 10 years with treatment[4] |

| Frequency | 3.6 million (2015)[8] |

Bulimia nervosa, also known simply as bulimia, is an eating disorder characterized by binge eating (eating large quantities of food in a short period of time, often feeling out of control) followed by compensatory behaviors, such as vomiting, excessive exercise, or fasting to prevent weight gain.[9]

Other efforts to lose weight may include the use of diuretics, stimulants, water fasting, or excessive exercise.[2] Most people with bulimia are at normal weight and have higher risk for other mental disorders, such as depression, anxiety, borderline personality disorder, bipolar disorder, and problems with drugs to alcohol. There is also a higher risk of suicide and self-harm.

Bulimia is more common among those who have a close relative with the condition.[2] The percentage risk that is estimated to be due to genetics is between 30% and 80%.[4] Other risk factors for the disease include psychological stress, cultural pressure to attain a certain body type, poor self-esteem, and obesity.[2][4] Living in a culture that commercializes or glamorizes dieting, and having parental figures who fixate on weight are also risks.[4]

Diagnosis is based on a person's medical history;[5] however, this is difficult, as people are usually secretive about their binge eating and purging habits.[4] Further, the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa takes precedence over that of bulimia.[4] Other similar disorders include binge eating disorder, Kleine–Levin syndrome, and borderline personality disorder.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Bulimia typically involves rapid and out-of-control eating, which is followed by self-induced vomiting or other forms of purging.[11][9] This cycle may be repeated several times a week or, in more serious cases, several times a day[12] and may directly cause:

- Dehydration

- Electrolyte imbalance can lead to abnormal heart rhythms, cardiac arrest, and even death

- Oral trauma, lacerations to the lining of the mouth or throat due to forced throwing up movements.[13]

- Russell's sign: calluses on knuckles and back of hands due to repeated trauma from incisors[14][15]

- Swollen salivary glands (in the neck, under the jawline)[16][17]

- Gastrointestinal problems, like constipation and acid reflux[13]

- Constipation or diarrhea

- Hypotension

- Infertility and/or irregular menstrual cycles

- Weight Fluctuations

These are some of the many signs that may indicate whether someone has bulimia nervosa:[18]

- A fixation on the number of calories consumed

- A fixation on an extreme consciousness of one's weight

- Low self-esteem and/or self-harming

- Suicidal tendencies

- An irregular menstrual cycle in women

- Regular trips to the bathroom, especially soon after eating

- Depression, anxiety disorders, and sleep disorders

- Frequent occurrences involving the consumption of abnormally large portions of food[19]

- The use of laxatives, diuretics, and diet pills

- Compulsive or excessive exercise

- Unhealthy/dry skin, hair, nails, and lips

- Fatigue, or exhaustion

As with many psychiatric illnesses, delusions can occur, in conjunction with other signs and symptoms, leaving the person with a false belief that is not ordinarily accepted by others.[20]

People with bulimia nervosa may also exercise to a point that excludes other activities.[20]

Interoceptive

[edit]People with bulimia exhibit several interoceptive deficits, in which one experiences impairment in recognizing and discriminating between internal sensations, feelings, and emotions.[21] People with bulimia may also react negatively to somatic and affective states.[22] Regarding interoceptive sensation, hyposensitive individuals may not detect normal feelings of fullness at the appropriate time while eating, and are prone to eating more calories in a short period of time as a result of this decreased sensitivity.[21]

Examining from a neural basis also connects elements of interoception and emotion; notable overlaps occur in the medial prefrontal cortex, anterior and posterior cingulate, and anterior insula cortices, which are linked to both interoception and emotional eating.[23]

Related disorders

[edit]People with bulimia are at a higher risk to have an affective disorder, such as depression or general anxiety disorder. One study found 70% had depression at some time in their lives (as opposed to 26% for adult females in the general population), rising to 88% for all affective disorders combined.[24] Another study in the Journal of Affective Disorders found that of the population of patients that were diagnosed with an eating disorder according to the DSM-V guidelines about 27% also suffered from bipolar disorder. Within this article, the majority of the patients were diagnosed with bulimia nervosa, the second most common condition reported was binge-eating disorder.[25] Some individuals with anorexia nervosa exhibit episodes of bulimic tendencies through purging (either through self-induced vomiting or laxatives) as a way to quickly remove food in their system.[26] There may be an increased risk for diabetes mellitus type 2.[27] Bulimia also has negative effects on a person's teeth due to the acid passed through the mouth from frequent vomiting causing acid erosion, mainly on the posterior dental surface.

Research has shown that there is a relationship between bulimia and narcissism.[28][29][30] According to a study by the Australian National University, eating disorders are more susceptible among vulnerable narcissists. This can be caused by a childhood in which inner feelings and thoughts were minimized by parents, leading to "a high focus on receiving validation from others to maintain a positive sense of self".[31]

The medical journal Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation notes that a "substantial rate of patients with bulimia nervosa" also have borderline personality disorder.[32]

A study by the Psychopharmacology Research Program of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine "leaves little doubt that bipolar and eating disorders—particularly bulimia nervosa and bipolar II disorder—are related." The research shows that most clinical studies indicate that patients with bipolar disorder have higher rates of eating disorders, and vice versa. There is overlap in phenomenology, course, comorbidity, family history, and pharmacologic treatment response of these disorders. This is especially true of "eating dysregulation, mood dysregulation, impulsivity and compulsivity, craving for activity and/or exercise."[33]

Studies have shown a relationship between bulimia's effect on metabolic rate and caloric intake with thyroid dysfunction.[34]

Scientific research has shown that people suffering from bulimia have decreased volumes of brain matter, and that the abnormalities are reversible after long-term recovery.[35]

Causes

[edit]Biological

[edit]As with anorexia nervosa, there is evidence of genetic predispositions contributing to the onset of this eating disorder.[36] Abnormal levels of many hormones, notably serotonin, have been shown to be responsible for some disordered eating behaviors. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is under investigation as a possible mechanism.[37][38]

There is evidence that sex hormones may influence appetite and eating in women and the onset of bulimia nervosa. Studies have shown that women with hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovary syndrome have a dysregulation of appetite, along with carbohydrates and fats. This dysregulation of appetite is also seen in women with bulimia nervosa. In addition, gene knockout studies in mice have shown that mice that have the gene encoding estrogen receptors have decreased fertility due to ovarian dysfunction and dysregulation of androgen receptors. In humans, there is evidence that there is an association between polymorphisms in the ERβ (estrogen receptor β) and bulimia, suggesting there is a correlation between sex hormones and bulimia nervosa.[39]

Bulimia has been compared to drug addiction, though the empirical support for this characterization is limited.[40] However, people with bulimia nervosa may share dopamine D2 receptor-related vulnerabilities with those with substance use disorders.[41]

Dieting, a common behaviour in bulimics, is associated with lower plasma tryptophan levels.[42] Decreased tryptophan levels in the brain, and thus the synthesis of serotonin, such as via acute tryptophan depletion, increases bulimic urges in currently and formerly bulimic individuals within hours.[43][44]

Abnormal blood levels of peptides important for the regulation of appetite and energy balance are observed in individuals with bulimia nervosa, but it remains unknown if this is a state or trait.[45]

In recent years, evolutionary psychiatry as an emerging scientific discipline has been studying mental disorders from an evolutionary perspective. If eating disorders, Bulimia nervosa in particular, have evolutionary functions or if they are new modern "lifestyle" problems is still debated.[46][47][48]

Social

[edit]Media portrayals of an 'ideal' body shape are widely considered to be a contributing factor to bulimia.[20] In a 1991 study by Weltzin, Hsu, Pollicle, and Kaye, it was stated that 19% of bulimics undereat, 37% of bulimics eat an average or normal amount of food, and 44% of bulimics overeat.[49] A survey of 15- to 18-year-old high school girls in Nadroga, Fiji, found the self-reported incidence of purging rose from 0% in 1995 (a few weeks after the introduction of television in the province) to 11.3% in 1998.[50] In addition, the suicide rate among people with bulimia nervosa is 7.5 times higher than in the general population.[51]

When attempting to decipher the origin of bulimia nervosa in a cognitive context, Christopher Fairburn et al.'s cognitive-behavioral model is often considered the golden standard.[52] Fairburn et al.'s model discusses the process in which an individual falls into the binge-purge cycle and thus develops bulimia. Fairburn et al. argue that extreme concern with weight and shape coupled with low self-esteem will result in strict, rigid, and inflexible dietary rules. Accordingly, this would lead to unrealistically restricted eating, which may consequently induce an eventual "slip" where the individual commits a minor infraction of the strict and inflexible dietary rules. Moreover, the cognitive distortion due to dichotomous thinking leads the individual to binge. The binge subsequently should trigger a perceived loss of control, promoting the individual to purge in hope of counteracting the binge. However, Fairburn et al. assert the cycle repeats itself, and thus consider the binge-purge cycle to be self-perpetuating.[53]

In contrast, Byrne and Mclean's findings differed slightly from Fairburn et al.'s cognitive-behavioral model of bulimia nervosa in that the drive for thinness was the major cause of purging as a way of controlling weight. In turn, Byrne and Mclean argued that this makes the individual vulnerable to binging, indicating that it is not a binge-purge cycle but rather a purge-binge cycle in that purging comes before bingeing. Similarly, Fairburn et al.'s cognitive-behavioral model of bulimia nervosa is not necessarily applicable to every individual and is certainly reductionist. Every one differs from another, and taking such a complex behavior like bulimia and applying the same one theory to everyone would certainly be invalid. In addition, the cognitive-behavioral model of bulimia nervosa is very culturally bound in that it may not be necessarily applicable to cultures outside of Western society. To evaluate, Fairburn et al..'s model and more generally the cognitive explanation of bulimia nervosa is more descriptive than explanatory, as it does not necessarily explain how bulimia arises. Furthermore, it is difficult to ascertain cause and effect, because it may be that distorted eating leads to distorted cognition rather than vice versa.[54][55]

A considerable amount of literature has identified a correlation between sexual abuse and the development of bulimia nervosa. The reported incident rate of unwanted sexual contact is higher among those with bulimia nervosa than anorexia nervosa.[56]

When exploring the etiology of bulimia through a socio-cultural perspective, the "thin ideal internalization" is significantly responsible. The thin-ideal internalization is the extent to which individuals adapt to the societal ideals of attractiveness. Studies have shown that young women that read fashion magazines tend to have more bulimic symptoms than those women who do not. This further demonstrates the impact of media on the likelihood of developing the disorder.[57] Individuals first accept and "buy into" the ideals, and then attempt to transform themselves in order to reflect the societal ideals of attractiveness. J. Kevin Thompson and Eric Stice claim that family, peers, and most evidently media reinforce the thin ideal, which may lead to an individual accepting and "buying into" the thin ideal. In turn, Thompson and Stice assert that if the thin ideal is accepted, one could begin to feel uncomfortable with their body shape or size since it may not necessarily reflect the thin ideal set out by society. Thus, people feeling uncomfortable with their bodies may result in body dissatisfaction and may develop a certain drive for thinness. Consequently, body dissatisfaction coupled with a drive for thinness is thought to promote dieting and negative effects, which could eventually lead to bulimic symptoms such as purging or bingeing. Binges lead to self-disgust which causes purging to prevent weight gain.[58]

A study dedicated to investigating the thin ideal internalization as a factor of bulimia nervosa is Thompson's and Stice's research. Their study aimed to investigate how and to what degree media affects the thin ideal internalization. Thompson and Stice used randomized experiments (more specifically programs) dedicated to teaching young women how to be more critical when it comes to media, to reduce thin-ideal internalization. The results showed that by creating more awareness of the media's control of the societal ideal of attractiveness, the thin ideal internalization significantly dropped. In other words, less thin ideal images portrayed by the media resulted in less thin-ideal internalization. Therefore, Thompson and Stice concluded that media greatly affected the thin ideal internalization.[59] Papies showed that it is not the thin ideal itself, but rather the self-association with other persons of a certain weight that decide how someone with bulimia nervosa feels. People that associate themselves with thin models get in a positive attitude when they see thin models and people that associate with overweight get in a negative attitude when they see thin models. Moreover, it can be taught to associate with thinner people.[60]

Diagnosis

[edit]The onset of bulimia nervosa is often during adolescence, between 13 and 20 years of age, and many cases have previously experienced obesity, with many relapsing in adulthood into episodic bingeing and purging even after initially successful treatment and remission.[61] A lifetime prevalence of 0.5 percent and 0.9 percent for adults and adolescents, respectively, is estimated among the United States population.[62] Bulimia nervosa may affect up to 1% of young women and, after 10 years of diagnosis, half will recover fully, a third will recover partially, and 10–20% will still have symptoms.[4]

Adolescents with bulimia nervosa are more likely to have self-imposed perfectionism and compulsivity issues in eating compared to their peers. This means that the high expectations and unrealistic goals that these individuals set for themselves are internally motivated rather than by social views or expectations.[63]

Criteria

[edit]Bulimia Nervosa is diagnosed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The diagnostic criteria includes the following:[13][64]

- Recurrent episodes of binge eating

- Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behavior to prevent weight gain, like self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives or other medications, fasting, or excessive exercise.

- The binge eating and compensatory behaviors both occur at least once a week for three months

- Self-evaluation is influenced by body shape and weight.

Other methods are also used to narrow down the diagnosis, including:

- Physical exams: May include measuring your height and weight, checking vital signs, checking skin and nails, and listening to the heart and lungs.

- Lab tests: May include a complete blood count, tests to check electrolytes and protein, or a urinalysis might be performed.

- Psychological evaluations: A therapist or mental health provider will likely inquire about your thoughts, feelings, and eating habits, as well as asking you to complete a questionnaire.

Treatment

[edit]There are two main types of treatment given to those with bulimia nervosa; psychopharmacological and psychosocial treatments.[65]

Psychotherapy

[edit]Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is considered the gold standard for the treatment of bulimia nervosa. This approach focuses on helping patients identify and change distorted thought patterns related to eating, body image, and self worth[66][67]

CBT helps patients identify and challenge the distorted thinking individuals might have about food, weight and body image. It also helps by offering the chance to identify the unhelpful thoughts about food and body image.[67]

By using CBT people record how much food they eat and periods of vomiting with the purpose of identifying and avoiding emotional fluctuations that bring on episodes of bulimia on a regular basis, as a component of this therapy is food journaling.[68] CBT is necessarily good for those with bulimia as it targets the binge-purge cycle, which is the hallmark of bulimia.[9][69][70] People undergoing CBT who exhibit early behavioral changes are most likely to achieve the best treatment outcomes in the long run.[71]

Researchers have also reported some positive outcomes for interpersonal psychotherapy and dialectical behavior therapy.[72][73] These therapies have good outcomes for treating bulimia, especially in patients with emotional regulation difficulties or interpersonal issues. While these therapies are not as extensively research as CBT, they can be beneficial when integrated into a comprehensive treatment plan.[66]

For adolescents, Family-Based therapy (FBT) has been identified as an effective treatment. FBT involes the family in the treatment process, where parents are empowered to take an active role in helping their child recover from bulimia nervosa. This approach is particularly helpful in younger patients who are still living with their families[66]

The use of CBT has been shown to be quite effective for treating bulimia nervosa (BN) in adults, but little research has been done on effective treatments of BN for adolescents.[74] Although CBT is seen as more cost-efficient and helps individuals with BN in self-guided care, Family Based Treatment (FBT) might be more helpful to younger adolescents who need more support and guidance from their families.[75] Adolescents are at the stage where their brains are still quite malleable and developing gradually.[76] Therefore, young adolescents with BN are less likely to realize the detrimental consequences of becoming bulimic and have less motivation to change,[77] which is why FBT would be useful to have families intervene and support the teens.[74] Working with BN patients and their families in FBT can empower the families by having them involved in their adolescent's food choices and behaviors, taking more control of the situation in the beginning and gradually letting the adolescent become more autonomous when they have learned healthier eating habits.[74]

Medication

[edit]Antidepressants, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), are often prescribed to treat bulimia nervosa, especially when comorbid depression or anxiety disorders are present. However, medications alone are generally not sufficient and are typically used in conjunction with psychotherapy[13][66] Compared to placebo, the use of a single antidepressant has been shown to be effective.[78] Combining medication with counseling can improve outcomes in some circumstances.[79] Some positive outcomes of treatments can include: abstinence from binge eating, a decrease in obsessive behaviors to lose weight and in shape preoccupation, less severe psychiatric symptoms, a desire to counter the effects of binge eating, as well as an improvement in social functioning and reduced relapse rates.[4]

A combination of psychotherapy, especially CBT and pharmacological treatments, such as SSRIs, often lead to better outcomes for individuals with bulimia. Combining both approaches is particularly beneficial in severe or chronic cases, where behavioral modification and mood stabilization are crucial.[66]

Alternative medicine

[edit]Some researchers have also claimed positive outcomes in hypnotherapy.[80] The first use of hypnotherapy in Bulimic patients was in 1981. When it comes to hypnotherapy, Bulimic patients are easier to hypnotize than Anorexia Nervosa patients. In Bulimic patients, hypnotherapy focuses on learning self-control when it comes to binging and vomiting, strengthening stimulus control techniques, enhancing ones ego, improving weight control, and helping overweight patients see their body differently (have a different image).[81]

Risk factors

[edit]Being female and having bulimia nervosa takes a toll on mental health. Women frequently reported an onset of anxiety at the same time of the onset of bulimia nervosa.[82] The approximate female-to-male ratio of diagnosis is 10:1.[5] In addition to cognitive, genetic, and environmental factors, childhood gastrointestinal problems and early pubertal maturation also increase the likelihood of developing bulimia nervosa.[83] Another concern with eating disorders is developing a coexisting substance use disorder.[84]

Epidemiology

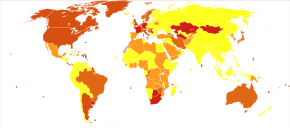

[edit]

There is little data on the percentage of people with bulimia in general populations.[5] Most studies conducted thus far have been on convenience samples from hospital patients, high school or university students; research on bulimia nervosa among ethnic minorities has also been limited.[85] Existing studies have yielded a wide range of results: between 0.1% and 1.4% of males, and between 0.3% and 9.4% of females.[86] Studies on time trends in the prevalence of bulimia nervosa have also yielded inconsistent results.[87] According to Gelder, Mayou and Geddes (2005) bulimia nervosa is prevalent between 1 and 2 percent of women aged 15–40 years. Bulimia nervosa occurs more frequently in developed countries[68] and in cities, with one study finding that bulimia is five times more prevalent in cities than in rural areas.[88] There is a perception that bulimia is most prevalent amongst girls from middle-class families;[89] however, in a 2009 study girls from families in the lowest income bracket studied were 153 percent more likely to be bulimic than girls from the highest income bracket.[90] According to a study conducted in 2022 by Silen et al., which conglomerated statistics using various methods such as SCID, MRFS, EDE, SSAGA, and EDDI, the US, Finland, Australia, and the Netherlands had an estimated 2.1%, 2.4%, 1.0%, and 0.8% prevalence of bulimia nervosa among females under 30 years of age.[91] This demonstrates the prevalence of bulimia nervosa in developed, Western, first-world countries, indicating an urgency in treating adolescent women. Additionally, these statistics may be misrepresentative of the true population affected with bulimia nervosa due to potential underreporting bias.

There are higher rates of eating disorders in groups involved in activities which idealize a slim physique, such as dance,[92] gymnastics, modeling, cheerleading, running, acting, swimming, diving, rowing and figure skating. Bulimia is thought to be more prevalent among whites;[93] however, a more recent study showed that African-American teenage girls were 50 percent more likely than white girls to exhibit bulimic behavior, including both binging and purging.[94]

| Country | Year | Sample size and type | % affected | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portugal | 2006 | 2,028 high school students | 0.3% female[95] | |

| Brazil | 2004 | 1,807 students (ages 7–19) | 0.8% male | 1.3% female[96] |

| Spain | 2004 | 2,509 female adolescents (ages 13–22) | 1.4% female[97] | |

| Hungary | 2003 | 580 Budapest residents | 0.4% male | 3.6% female[92] |

| Australia | 1998 | 4,200 high school students | 0.3% combined[98] | |

| United States | 1996 | 1,152 college students | 0.2% male | 1.3% female[99] |

| Norway | 1995 | 19,067 psychiatric patients | 0.7% male | 7.3% female[100] |

| Canada | 1995 | 8,116 (random sample) | 0.1% male | 1.1% female[101] |

| Japan | 1995 | 2,597 high school students | 0.7% male | 1.9% female[102] |

| United States | 1992 | 799 college students | 0.4% male | 5.1% female[103] |

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]The term bulimia comes from Greek βουλιμία boulīmia, "ravenous hunger", a compound of βοῦς bous, "ox" and λιμός, līmos, "hunger".[104] Literally, the scientific name of the disorder, bulimia nervosa, translates to "nervous ravenous hunger".

Before the 20th century

[edit]Although diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa did not appear until 1979, evidence suggests that binging and purging were popular in certain ancient cultures. The first documented account of behavior resembling bulimia nervosa was recorded in Xenophon's Anabasis around 370 B.C, in which Greek soldiers purged themselves in the mountains of Asia Minor. It is unclear whether this purging was preceded by binging.[105] In ancient Egypt, physicians recommended purging once a month for three days to preserve health.[106] This practice stemmed from the belief that human diseases were caused by the food itself. In ancient Rome, elite society members would vomit to "make room" in their stomachs for more food at all-day banquets.[106] Emperors Claudius and Vitellius both were gluttonous and obese, and they often resorted to habitual purging.[106]

Historical records also suggest that some saints who developed anorexia (as a result of a life of asceticism) may also have displayed bulimic behaviors.[106] Saint Mary Magdalen de Pazzi (1566–1607) and Saint Veronica Giuliani (1660–1727) were both observed binge eating—giving in, as they believed, to the temptations of the devil.[106] Saint Catherine of Siena (1347–1380) is known to have supplemented her strict abstinence from food by purging as reparation for her sins. Catherine died from starvation at age thirty-three.[106]

While the psychological disorder "bulimia nervosa" is relatively new, the word "bulimia", signifying overeating, has been present for centuries.[106] The Babylon Talmud referenced practices of "bulimia", yet scholars believe that this simply referred to overeating without the purging or the psychological implications bulimia nervosa.[106] In fact, a search for evidence of bulimia nervosa from the 17th to late 19th century revealed that only a quarter of the overeating cases they examined actually vomited after the binges. There was no evidence of deliberate vomiting or an attempt to control weight.[106]

20th century

[edit]Globally, bulimia was estimated to affect 3.6 million people in 2015.[8] About 1% of young women have bulimia at a given point in time and about 2% to 3% of women have the condition at some point in their lives.[3] The condition is less common in the developing world.[4] Bulimia is about nine times more likely to occur in women than men.[5] Among women, rates are highest in young adults.[5] Bulimia was named and first described by the British psychiatrist Gerald Russell in 1979.[107][108]

At the turn of the century, bulimia (overeating) was described as a clinical symptom, but rarely in the context of weight control.[109] Purging, however, was seen in anorexic patients and attributed to gastric pain rather than another method of weight control.[109]

In 1930, admissions of anorexia nervosa patients to the Mayo Clinic from 1917 to 1929 were compiled. Fifty-five to sixty-five percent of these patients were reported to be voluntarily vomiting to relieve weight anxiety.[109] Records show that purging for weight control continued throughout the mid-1900s. Several case studies from this era reveal patients with the modern description of bulimia nervosa.[109] In 1939, Rahman and Richardson reported that out of their six anorexic patients, one had periods of overeating, and another practiced self-induced vomiting.[109] Wulff, in 1932, treated "Patient D", who would have periods of intense cravings for food and overeat for weeks, which often resulted in frequent vomiting.[106] Patient D, who grew up with a tyrannical father, was repulsed by her weight and would fast for a few days, rapidly losing weight. Ellen West, a patient described by Ludwig Binswanger in 1958, was teased by friends for being fat and excessively took thyroid pills to lose weight, later using laxatives and vomiting.[106] She reportedly consumed dozens of oranges and several pounds of tomatoes each day, yet would skip meals. After being admitted to a psychiatric facility for depression, Ellen ate ravenously yet lost weight, presumably due to self-induced vomiting.[106] However, while these patients may have met modern criteria for bulimia nervosa, they cannot technically be diagnosed with the disorder, as it had not yet appeared in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders at the time of their treatment.[106]

An explanation for the increased instances of bulimic symptoms may be due to the 20th century's new ideals of thinness.[109] The shame of being fat emerged in the 1940s when teasing remarks about weight became more common. The 1950s, however, truly introduced the trend of aspiration for thinness.[109]

In 1979, Gerald Russell first published a description of bulimia nervosa, in which he studied patients with a "morbid fear of becoming fat" who overate and purged afterward.[107] He specified treatment options and indicated the seriousness of the disease, which can be accompanied by depression and suicide.[107] In 1980, bulimia nervosa first appeared in the DSM-III.[107]

After its appearance in the DSM-III, there was a sudden rise in the documented incidents of bulimia nervosa.[106] In the early 1980s, incidents of the disorder rose to about 40 in every 100,000 people.[106] This decreased to about 27 in every 100,000 people at the end of the 1980s/early 1990s.[106] However, bulimia nervosa's prevalence was still much higher than anorexia nervosa's, which at the time occurred in about 14 people per 100,000.[106]

In 1991, Kendler et al. documented the cumulative risk for bulimia nervosa for those born before 1950, from 1950 to 1959, and after 1959.[110] The risk for those born after 1959 is much higher than those in either of the other cohorts.[110]

See also

[edit]- Anorectic Behavior Observation Scale

- Eating recovery

- Evolutionary psychiatry

- Binge eating disorder

- List of people with bulimia nervosa

References

[edit]- ^ Bulik CM, Marcus MD, Zerwas S, Levine MD, La Via M (October 2012). "The changing "weightscape" of bulimia nervosa". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 169 (10): 1031–6. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010147. PMC 4038540. PMID 23032383.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Bulimia nervosa fact sheet". Office on Women's Health. July 16, 2012. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ a b Smink FR, van Hoeken D, Hoek HW (August 2012). "Epidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality rates". Current Psychiatry Reports. 14 (4): 406–14. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y. PMC 3409365. PMID 22644309.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hay PJ, Claudino AM (July 2010). "Bulimia nervosa". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2010: 1009. PMC 3275326. PMID 21418667.

- ^ a b c d e f g h American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fifth ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 345–349. ISBN 978-0-89042-555-8.

- ^ Hay P (July 2013). "A systematic review of evidence for psychological treatments in eating disorders: 2005-2012". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 46 (5): 462–9. doi:10.1002/eat.22103. PMID 23658093.

- ^ McElroy SL, Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, O'Melia AM (October 2012). "Current pharmacotherapy options for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 13 (14): 2015–26. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.721781. PMID 22946772. S2CID 1747393.

- ^ a b Vos T, Allen C, Arora M, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Brown A, et al. (GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators) (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ a b c "Bulimia nervosa - Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2024-12-05.

- ^ Dorfman J, The Center for Special Dentistry Archived February 11, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Steinhausen, Hans-Christoph; Weber, Sandy (December 2009). "The Outcome of Bulimia Nervosa: Findings From One-Quarter Century of Research". American Journal of Psychiatry. 166 (12): 1331–1341. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040582. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 19884225.

- ^ "Bulimia Nervosa" (PDF). Let's Talk Facts: 1. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 19, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Clinic, Cleavland (May 15, 2022). "Bulimia Nervosa".

- ^ Joseph AB, Herr B (May 1985). "Finger calluses in bulimia". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 142 (5): 655a–655. doi:10.1176/ajp.142.5.655a. PMID 3857013.

- ^ Wynn DR, Martin MJ (October 1984). "A physical sign of bulimia". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 59 (10): 722. doi:10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62063-1. PMID 6592415.

- ^ "Eating Disorders". Oral Health Topics A–Z. American Dental Association. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009.

- ^ Mcgilley BM, Pryor TL (June 1998). "Assessment and treatment of bulimia nervosa". American Family Physician. 57 (11): 2743–50. PMID 9636337.

- ^ "Symptoms Of Bulimia Nervosa". Illawarra Mercury. February 23, 2001. Archived from the original on February 21, 2016.

- ^ "Bulimia Nervosa". Proud2BME. The National Eating Disorders Association. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c Barker P (2003). Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing: The Craft of Caring. Great Britain: Arnold. ISBN 978-0340810262.[page needed]

- ^ a b Boswell JF, Anderson LM, Anderson DA (June 2015). "Integration of Interoceptive Exposure in Eating Disorder Treatment". Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 22 (2): 194–210. doi:10.1111/cpsp.12103.

- ^ Badoud D, Tsakiris M (June 2017). "From the body's viscera to the body's image: Is there a link between interoception and body image concerns?". Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 77: 237–246. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.03.017. PMID 28377099. S2CID 768206.

- ^ Barrett LF, Simmons WK (July 2015). "Interoceptive predictions in the brain". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 16 (7): 419–29. doi:10.1038/nrn3950. PMC 4731102. PMID 26016744.

- ^ Walsh BT, Roose SP, Glassman AH, Gladis M, Sadik C (1985). "Bulimia and depression". Psychosomatic Medicine. 47 (2): 123–31. doi:10.1097/00006842-198503000-00003. PMID 3863157. S2CID 12748691.

- ^ McElroy, Susan L.; Crow, Scott; Blom, Thomas J.; Biernacka, Joanna M.; Winham, Stacey J.; Geske, Jennifer; Cuellar-Barboza, Alfredo B.; Bobo, William V.; Prieto, Miguel L.; Veldic, Marin; Mori, Nicole; Seymour, Lisa R.; Bond, David J.; Frye, Mark A. (February 2016). "Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in patients with bipolar disorder". Journal of Affective Disorders. 191: 216–221. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.010. PMID 26682490.

- ^ Carlson, N.R., et al. (2007). Psychology: The Science of Behaviour – 4th Canadian ed. Toronto, ON: Pearson Education Canada.[page needed]

- ^ Nieto-Martínez R, González-Rivas JP, Medina-Inojosa JR, Florez H (November 2017). "Are Eating Disorders Risk Factors for Type 2 Diabetes? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Current Diabetes Reports. 17 (12): 138. doi:10.1007/s11892-017-0949-1. PMID 29168047. S2CID 3688434.

- ^ Maples J, Collins B, Miller JD, Fischer S, Seibert A (January 2011). "Differences between grandiose and vulnerable narcissism and bulimic symptoms in young women". Eat Behav. 12 (1): 83–5. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.10.001. PMID 21184981.

- ^ Steiger H, Jabalpurwala S, Champagne J, Stotland S (September 1997). "A controlled study of trait narcissism in anorexia and bulimia nervosa". Int J Eat Disord. 22 (2): 173–8. doi:10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199709)22:2<173::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-c. PMID 9261656.

- ^ Steinberg BE, Shaw RJ (1997). "Bulimia as a disturbance of narcissism: self-esteem and the capacity to self-soothe". Addict Behav. 22 (5): 699–710. doi:10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00009-9. PMID 9347071. S2CID 25050604.

- ^ Sivanathan D, Bizumic B, Rieger E, Huxley E (December 2019). "Vulnerable narcissism as a mediator of the relationship between perceived parental invalidation and eating disorder pathology". Eat Weight Disord. 24 (6): 1071–1077. doi:10.1007/s40519-019-00647-2. PMID 30725304. S2CID 73416090.

- Lay summary in: "Vulnerable narcissists more susceptible to eating disorders". ANU College of Health & Medicine.

- ^ Hessler, Johannes Baltasar; Heuser, Jörg; Schlegl, Sandra; Bauman, Tabea; Greetfeld, Martin; Voderholzer, Ulrich (2019). "Impact of comorbid borderline personality disorder on inpatient treatment for bulimia nervosa: Analysis of routine data". Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation. 6: 1. doi:10.1186/s40479-018-0098-4. PMC 6335811. PMID 30680217.

- ^ McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Keck PE, Akiskal HS (June 2005). "Comorbidity of bipolar and eating disorders: distinct or related disorders with shared dysregulations?". J Affect Disord. 86 (2–3): 107–27. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.008. PMID 15935230.

- ^ Altemus M, Hetherington M, Kennedy B, Licinio J, Gold PW (April 1996). "Thyroid function in bulimia nervosa". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 21 (3): 249–61. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(96)00002-9. PMID 8817724. S2CID 24919021.

- ^ Wagner, Angela; Greer, Phil; Bailer, Ursula F.; Frank, Guido K.; Henry, Shannan E.; Putnam, Karen; Meltzer, Carolyn C.; Ziolko, Scott K.; Hoge, Jessica; McConaha, Claire; Kaye, Walter H. (2006-02-01). "Normal Brain Tissue Volumes after Long-Term Recovery in Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa". Biological Psychiatry. 59 (3): 291–293. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.06.014. PMID 16139807.

- ^ "Biological Causes of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa". Archived from the original on May 2, 2016. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ^ Ribasés M, Gratacòs M, Fernández-Aranda F, Bellodi L, Boni C, Anderluh M, et al. (June 2004). "Association of BDNF with anorexia, bulimia and age of onset of weight loss in six European populations". Human Molecular Genetics. 13 (12): 1205–12. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh137. PMID 15115760.

- ^ Wonderlich S, Mitchell JE, de Zwaan M, Steiger H, eds. (2018). "Psychobiology of eating disorders". Annual Review of Eating Disorders – part 2. Radcliffe Publishing. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1-84619-244-9.

- ^ Hirschberg AL (March 2012). "Sex hormones, appetite and eating behaviour in women". Maturitas. 71 (3): 248–56. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.016. PMID 22281161.

- ^ Broft A, Shingleton R, Kaufman J, Liu F, Kumar D, Slifstein M, et al. (July 2012). "Striatal dopamine in bulimia nervosa: a PET imaging study". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 45 (5): 648–56. doi:10.1002/eat.20984. PMC 3640453. PMID 22331810.

- ^ Kaye WH, Wierenga CE, Bailer UF, Simmons AN, Wagner A, Bischoff-Grethe A (May 2013). "Does a shared neurobiology for foods and drugs of abuse contribute to extremes of food ingestion in anorexia and bulimia nervosa?". Biological Psychiatry. 73 (9): 836–42. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.01.002. PMC 3755487. PMID 23380716.

- ^ Strasser B, Fuchs D (2016). "Diet Versus Exercise in Weight Loss and Maintenance: Focus on Tryptophan". International Journal of Tryptophan Research. 9: 9–16. doi:10.4137/IJTR.S33385. PMC 4864009. PMID 27199566.

- ^ Smith KA, Fairburn CG, Cowen PJ (February 1999). "Symptomatic relapse in bulimia nervosa following acute tryptophan depletion". Archives of General Psychiatry. 56 (2): 171–6. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.2.171. PMID 10025442.

- ^ Weltzin TE, Fernstrom MH, Fernstrom JD, Neuberger SK, Kaye WH (November 1995). "Acute tryptophan depletion and increased food intake and irritability in bulimia nervosa". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 152 (11): 1668–71. doi:10.1176/ajp.152.11.1668. PMID 7485633.

- ^ Tortorella A, Brambilla F, Fabrazzo M, Volpe U, Monteleone AM, Mastromo D, Monteleone P (September 2014). "Central and peripheral peptides regulating eating behaviour and energy homeostasis in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a literature review". European Eating Disorders Review. 22 (5): 307–20. doi:10.1002/erv.2303. PMID 24942507.

- ^ Abed RT (December 1998). "The sexual competition hypothesis for eating disorders". Br J Med Psychol. 71 ( Pt 4) (4): 525–47. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1998.tb01007.x. PMID 9875960.

- ^ Nettersheim J, Gerlach G, Herpertz S, Abed R, Figueredo AJ, Brüne M (2018). "Evolutionary Psychology of Eating Disorders: An Explorative Study in Patients With Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa". Front Psychol. 9: 2122. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02122. PMC 6220092. PMID 30429818.

- ^ Nesse RM (2020). Good reasons for bad feelings: insights from the frontier of evolutionary psychiatry. Penguin Books, Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-198491-9. OCLC 1100591660.[page needed]

- ^ Carlson NR, Buskist W, Heth CD, Schmaltz R (2010). Psychology: the science of behaviour (4th Canadian ed.). Toronto: Pearson Education Canada. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-205-70286-2.

- ^ Becker AE, Burwell RA, Gilman SE, Herzog DB, Hamburg P (June 2002). "Eating behaviours and attitudes following prolonged exposure to television among ethnic Fijian adolescent girls". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 180 (6): 509–14. doi:10.1192/bjp.180.6.509. PMID 12042229.

- ^ Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan (2014). "Bulimia Nervosa" Abnormal Psychology. 6e. pg 344.

- ^ Cooper Z, Fairburn CG (2013). "The Evolution of "Enhanced" Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Eating Disorders: Learning From Treatment Nonresponse". Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 18 (3): 394–402. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.07.007. PMC 3695554. PMID 23814455.

- ^ Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (April 1990). "Studies of the epidemiology of bulimia nervosa". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 147 (4): 401–8. doi:10.1176/ajp.147.4.401. PMID 2180327.

- ^ Trull T (2010-10-08). Abnormal Psychology and Life: A Dimensional Approach. Belmont CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. pp. 236–8. ISBN 978-1-111-34376-7. Archived from the original on 2016-02-07.

- ^ Byrne SM, McLean NJ (January 2002). "The cognitive-behavioral model of bulimia nervosa: a direct evaluation". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 31 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1002/eat.10002. PMID 11835294.

- ^ Waller G (July 1992). "Sexual abuse and the severity of bulimic symptoms". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 161: 90–3. doi:10.1192/bjp.161.1.90. PMID 1638336. S2CID 39739310.

- ^ Nolen-Hoeksema S (2013). (Ab)normal Psychology. McGraw Hill. p. 338. ISBN 978-0078035388.

- ^ Zieve D. "Bulimia". PubMed Health. Archived from the original on February 11, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- ^ Thompson JK, Stice E (2001). "Thin-Ideal Internalization: Mounting Evidence for a New Risk Factor for Body-Image Disturbance and Eating Pathology". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 10 (5): 181–3. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00144. JSTOR 20182734. S2CID 20401750.

- ^ Papies EK, Nicolaije KA (January 2012). "Inspiration or deflation? Feeling similar or dissimilar to slim and plus-size models affects self-evaluation of restrained eaters". Body Image. 9 (1): 76–85. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.08.004. PMID 21962524.

- ^ Shader RI (2004). Manual of Psychiatric Therapeutics. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-4459-1.[page needed]

- ^ [Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2013)."(Ab)normal Psychology"(6th edition). McGraw-Hill. p.344]

- ^ Castro-Fornieles J, Gual P, Lahortiga F, Gila A, Casulà V, Fuhrmann C, et al. (September 2007). "Self-oriented perfectionism in eating disorders". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 40 (6): 562–8. doi:10.1002/eat.20393. PMID 17510925.

- ^ Harrington, Brian C.; Jimerson, Michelle; Haxton, Christina; Jimerson, David C. (2015-01-01). "Initial Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa". American Family Physician. 91 (1): 46–52. PMID 25591200.

- ^ Hoste RR, Labuschagne Z, Le Grange D (August 2012). "Adolescent bulimia nervosa". Current Psychiatry Reports. 14 (4): 391–7. doi:10.1007/s11920-012-0280-0. PMID 22614677. S2CID 36665983.

- ^ a b c d e Hay, Phillipia (Jul 19, 2010). "Bulimia Nervosa". BMJ Clinical Evidence: 1009. PMC 3275326. PMID 21418667.

- ^ a b Hagan, Kelsey E.; Walsh, B. Timothy (2021-01-01). "State of the Art: The Therapeutic Approaches to Bulimia Nervosa". Clinical Therapeutics. 43 (1): 40–49. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2020.10.012. ISSN 0149-2918. PMC 7902447. PMID 33358256.

- ^ a b Gelder MG, Mayou R, Geddes J (2005). Psychiatry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852863-0.[page needed]

- ^ Agras WS, Crow SJ, Halmi KA, Mitchell JE, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC (August 2000). "Outcome predictors for the cognitive behavior treatment of bulimia nervosa: data from a multisite study". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 157 (8): 1302–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1302. PMID 10910795.

- ^ Wilson GT, Loeb KL, Walsh BT, Labouvie E, Petkova E, Liu X, Waternaux C (August 1999). "Psychological versus pharmacological treatments of bulimia nervosa: predictors and processes of change". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 67 (4): 451–9. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.583.7568. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.4.451. PMID 10450615.

- ^ Trunko ME, Rockwell RE, Curry E, Runfola C, Kaye WH (March 2007). "Management of bulimia nervosa". Women's Health. 3 (2): 255–65. doi:10.2217/17455057.3.2.255. PMID 19803857.

- ^ Fairburn CG, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Wilson GT, Stice E (December 2004). "Prediction of outcome in bulimia nervosa by early change in treatment". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (12): 2322–4. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2322. PMID 15569910.

- ^ Safer DL, Telch CF, Agras WS (April 2001). "Dialectical behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 158 (4): 632–4. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.632. PMID 11282700.

- ^ a b c Keel PK, Haedt A (January 2008). "Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for eating problems and eating disorders". Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 37 (1): 39–61. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.822.6191. doi:10.1080/15374410701817832. PMID 18444053. S2CID 16098576.

- ^ Nadeau PO, Leichner P (February 2009). "Treating Bulimia in Adolescents: A Family-Based Approach". Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 18 (1): 67–68. PMC 2651218.

- ^ Le Grange D, Lock J, Dymek M (2003). "Family-based therapy for adolescents with bulimia nervosa". American Journal of Psychotherapy. 57 (2): 237–51. doi:10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2003.57.2.237. PMID 12817553.

- ^ Castro-Fornieles J, Bigorra A, Martinez-Mallen E, Gonzalez L, Moreno E, Font E, Toro J (2011). "Motivation to change in adolescents with bulimia nervosa mediates clinical change after treatment". European Eating Disorders Review. 19 (1): 46–54. doi:10.1002/erv.1045. PMID 20872926.

- ^ Bacaltchuk J, Hay P (2003). "Antidepressants versus placebo for people with bulimia nervosa". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD003391. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003391. PMC 6991155. PMID 14583971.

- ^ Bacaltchuk J, Hay P, Trefiglio R (2001). "Antidepressants versus psychological treatments and their combination for bulimia nervosa". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001 (4): CD003385. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003385. PMC 6999807. PMID 11687197.

- ^ Barabasz M (July 2007). "Efficacy of hypnotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders". The International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis. 55 (3): 318–35. doi:10.1080/00207140701338688. PMID 17558721. S2CID 9684032.

- ^ Vanderlinden, Johan; Vandereycken, Walter (September 1988). <673::aid-eat2260070511>3.0.co;2-r "The use of hypnotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 7 (5): 673–679. doi:10.1002/1098-108x(198809)7:5<673::aid-eat2260070511>3.0.co;2-r. ISSN 0276-3478.

- ^ Bulik, Cynthia M; Sullivan, Patrick F; Carter, Frances A; Joyce, Peter R (September 1996). "Lifetime anxiety disorders in women with bulimia nervosa". Comprehensive Psychiatry. 37 (5): 368–374. doi:10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90019-x. ISSN 0010-440X. PMID 8879912.

- ^ Jacobi, Corinna; Hayward, Chris; de Zwaan, Martina; Kraemer, Helena C.; Agras, W. Stewart (2004). "Coming to Terms With Risk Factors for Eating Disorders: Application of Risk Terminology and Suggestions for a General Taxonomy". Psychological Bulletin. 130 (1): 19–65. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 14717649.

- ^ Carbaugh, Rebecca; Sias, Shari (2010-04-01). "Comorbidity of Bulimia Nervosa and Substance Abuse: Etiologies, Treatment Issues, and Treatment Approaches". Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 32 (2): 125–138. doi:10.17744/mehc.32.2.j72865m4159p1420. ISSN 1040-2861.

- ^ Ruchkin, Vladislav; Isaksson, Johan; Schwab-Stone, Mary; Stickley, Andrew (2021-10-21). "Prevalence and early risk factors for bulimia nervosa symptoms in inner-city youth: gender and ethnicity perspectives". Journal of Eating Disorders. 9 (1): 136. doi:10.1186/s40337-021-00479-5. ISSN 2050-2974. PMC 8529812. PMID 34674763.

- ^ Makino M, Tsuboi K, Dennerstein L (September 2004). "Prevalence of eating disorders: a comparison of Western and non-Western countries". MedGenMed. 6 (3): 49. PMC 1435625. PMID 15520673.

- ^ Hay PJ, Mond J, Buttner P, Darby A (February 2008). Murthy RS (ed.). "Eating disorder behaviors are increasing: findings from two sequential community surveys in South Australia". PLOS ONE. 3 (2): e1541. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.1541H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001541. PMC 2212110. PMID 18253489.

- ^ van Son GE, van Hoeken D, Bartelds AI, van Furth EF, Hoek HW (December 2006). "Urbanisation and the incidence of eating disorders". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 189 (6): 562–3. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.021378. PMID 17139044.

- ^ "Bulimia". finddoctorsonline.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-09.

- ^ Grohol J (March 19, 2009). "Black Girls At Risk for Bulimia". Archived from the original on May 24, 2012.

- ^ Silén, Yasmina; Keski-Rahkonen, Anna (2022). "Worldwide prevalence of DSM-5 eating disorders among young people". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 35 (6): 362–371. doi:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000818. PMID 36125216.

- ^ a b Tölgyes T, Nemessury J (August 2004). "Epidemiological studies on adverse dieting behaviours and eating disorders among young people in Hungary". Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 39 (8): 647–54. doi:10.1007/s00127-004-0783-z. PMID 15300375. S2CID 23275345.

- ^ Franko DL, Becker AE, Thomas JJ, Herzog DB (March 2007). "Cross-ethnic differences in eating disorder symptoms and related distress". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 40 (2): 156–64. doi:10.1002/eat.20341. PMID 17080449.

- ^ McBride H. "Study Reveals Stunning Prevalence of Bulimia Among African-American Girls". Archived from the original on February 10, 2012.

- ^ Machado PP, Machado BC, Gonçalves S, Hoek HW (April 2007). "The prevalence of eating disorders not otherwise specified". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 40 (3): 212–7. doi:10.1002/eat.20358. hdl:1822/5722. PMID 17173324.

- ^ Vilela JE, Lamounier JA, Dellaretti Filho MA, Barros Neto JR, Horta GM (2004). "[Eating disorders in school children]" [Eating disorders in school children]. Jornal de Pediatria (in Portuguese). 80 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1590/S0021-75572004000100010. PMID 14978549.

- ^ Lahortiga-Ramos F, De Irala-Estévez J, Cano-Prous A, Gual-García P, Martínez-González MA, Cervera-Enguix S (March 2005). "Incidence of eating disorders in Navarra (Spain)". European Psychiatry. 20 (2): 179–85. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.07.008. PMID 15797704. S2CID 20615315.

- ^ Hay P (May 1998). "The epidemiology of eating disorder behaviors: an Australian community-based survey". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 23 (4): 371–82. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199805)23:4<371::AID-EAT4>3.0.CO;2-F. PMID 9561427.

- ^ Pemberton AR, Vernon SW, Lee ES (September 1996). "Prevalence and correlates of bulimia nervosa and bulimic behaviors in a racially diverse sample of undergraduate students in two universities in southeast Texas". American Journal of Epidemiology. 144 (5): 450–5. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008950. PMID 8781459.

- ^ Götestam KG, Eriksen L, Hagen H (November 1995). "An epidemiological study of eating disorders in Norwegian psychiatric institutions". The International Journal of Eating Disorders. 18 (3): 263–8. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199511)18:3<263::AID-EAT2260180308>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 8556022.

- ^ Garfinkel PE, Lin E, Goering P, Spegg C, Goldbloom DS, Kennedy S, et al. (July 1995). "Bulimia nervosa in a Canadian community sample: prevalence and comparison of subgroups". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 152 (7): 1052–8. doi:10.1176/ajp.152.7.1052. PMID 7793442.

- ^ Suzuki K, Takeda A, Matsushita S (July 1995). "Coprevalence of bulimia with alcohol abuse and smoking among Japanese male and female high school students". Addiction. 90 (7): 971–5. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90797110.x. PMID 7663319.

- ^ Heatherton TF, Nichols P, Mahamedi F, Keel P (November 1995). "Body weight, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms among college students, 1982 to 1992". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 152 (11): 1623–9. doi:10.1176/ajp.152.11.1623. PMID 7485625.

- ^ Douglas Harper (November 2001). "Online Etymology Dictionary: bulimia". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- ^ Giannini, A. J. (1993). "A history of bulimia". In The Eating disorders (pp. 18–21). Springer New York.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Russell, G. (1997). The history of bulimia nervosa. D. Garner & P. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of Treatment for Eating Disorders (2nd ed., pp. 11–24). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- ^ a b c d Russell G (August 1979). "Bulimia nervosa: an ominous variant of anorexia nervosa". Psychological Medicine. 9 (3): 429–48. doi:10.1017/S0033291700031974. PMID 482466. S2CID 23973384.

- ^ Palmer R (December 2004). "Bulimia nervosa: 25 years on". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 185 (6): 447–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.185.6.447. PMID 15572732.

- ^ a b c d e f g Casper RC (1983). "On the emergence of bulimia nervosa as a syndrome a historical view". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2 (3): 3–16. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198321)2:3<3::AID-EAT2260020302>3.0.CO;2-D.

- ^ a b Kendler KS, MacLean C, Neale M, Kessler R, Heath A, Eaves L (December 1991). "The genetic epidemiology of bulimia nervosa". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 148 (12): 1627–37. doi:10.1176/ajp.148.12.1627. PMID 1842216.