Cylinder (firearms)

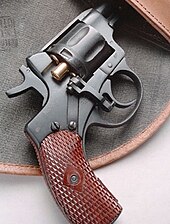

In firearms, the cylinder is the cylindrical, rotating part of a revolver containing multiple chambers, each of which is capable of holding a single cartridge. The cylinder rotates (revolves) around a central axis in the revolver's action to sequentially align each individual chamber with the barrel bore for repeated firing. Each time the gun is cocked, the cylinder indexes by one chamber (for five-shooters, by 72°, for six-shooters, by 60°, for seven-shooters, by 51.43°, for eight-shooters, by 45°, for nine-shooters, by 40°, and for ten-shooters, by 36°). Serving the same function as a rotary magazine, the cylinder stores ammunitions within the revolver and allows it to fire multiple times before needing to reload.

Typically revolver cylinders are designed to generally hold six cartridges (hence revolvers sometimes are referred to as "six-shooters"), but some small-frame concealable revolvers such as the Smith & Wesson Model 638 have a 5-shot cylinder, due to the smaller overall size and limited available space. The Nagant M1895 revolver has a 7-shot cylinder, the Webley-Fosbery Automatic Revolver has an 8-shot cylinder in .38 caliber, and the LeMat Revolver has a 9-shot cylinder. Several models of .22 rimfire-caliber revolvers have cylinders holding 9 or 10 rounds.

As a rule, cylinders are not designed to be detached from the firearm (except for cleaning). Rapid reloading is instead facilitated by the use of a speedloader or moon clip, although these work only on top-break and swing-out cylinder revolvers; revolvers having fixed cylinders must be unloaded and loaded one chamber at a time.

Designs

Fixed cylinder designs

The first generation of cartridge revolvers were converted caplock designs. In many of these (especially those that were converted long after manufacture), the pin on which the cylinder revolved was removed, and the cylinder was taken from the gun for loading. Later models used a loading gate at the rear of the cylinder that allowed one cartridge at a time to be inserted for loading, while a rod under the barrel could be pressed rearward to eject the fired case. Most revolvers using this method of loading are single-action revolvers.[1]

Oddly, the loading gate on the original Colt designs (and copied by nearly all single-action revolvers since) is on the right side, which may favor left-handed users; with the revolver held in the proper grip for shooting in the left hand, the cartridges can easily be ejected and loaded with the right. This was done because these pistols were intended for use with cavalry, and it was intended that the revolver and the reins would be held in the left hand while the right hand was free to eject and load the cartridges.[2]

Since the cylinder in these revolvers is firmly attached at the front and rear of the frame, and since the frame is typically full thickness all the way around, fixed-cylinder revolvers are inherently strong designs. Because of this, many modern large-caliber hunting revolvers tend to be based on the fixed-cylinder design. Fixed-cylinder revolvers can fire the strongest and most powerful cartridges, but at the price of being the slowest to load and unload and they cannot use speedloaders or moon clips for loading, as only one chamber is exposed at a time to the loading gate.[3]

Top break

The next method used for loading and unloading cartridge revolvers was the top break design. In a top-break revolver, the frame is hinged at the bottom front of the cylinder. Releasing the lock and pushing the barrel down brings the cylinder up, which exposes the rear of the cylinder for reloading. In most top-break revolvers, the act of pivoting the barrel and cylinder operates an extractor that pushes the cartridges in the chambers back far enough that they will fall free, or can be removed easily. Fresh rounds are then inserted into the cylinder, either one at a time or all at once with either a speedloader or a moon clip. The barrel and cylinder are then rotated back and locked in place, and the revolver is ready to fire. Since the frame is in two parts, held together by a latch on the top rear of the cylinder, top-break revolvers cannot handle high pressure or "magnum"-type rounds. Top-break designs are largely extinct in the world of firearms, but are still commonly found in airguns.[4]

One of the most famous "break-top" revolvers is the Webley service revolver (and the Enfield revolver, a nearly identical design), used by the British military from 1889 to 1963.[5] The American outlaw Jesse James used the 19th century Schofield Model 3 break-top revolver, and the Russian Empire issued the very similar .44 Russian calibre Smith & Wesson No. 3 Revolver from 1870 until 1895.[6]

Swing-out cylinder

The most modern method of loading and unloading a revolver is by means of the swing-out cylinder. The cylinder is mounted on a pivot that is coaxial with the chambers, and the cylinder swings out and down (to the left in most cases, as most people hold the gun right-handedly and uses the non-dominant left hand to load the cylinder). An extractor is fitted, operated by a rod projecting from the front of the cylinder assembly. When pressed, it will push all fired rounds free simultaneously (as in top-break models, the travel is designed to not completely extract longer, unfired rounds). The cylinder may then be loaded, singly or again with a speedloader, closed, and latched in place.[7]

The pivoting part that supports the cylinder is called the crane; it is the weak point of swing-out cylinder designs. Using the method often portrayed in movies, television, and videogames of flipping the cylinder open and closed with a flick of the wrist can in fact cause the crane to bend over time, throwing the cylinder out of alignment with the barrel. Lack of alignment between chamber and barrel is a dangerous condition, as it can impede the bullet's transition from chamber to barrel. This gives rise to higher pressures in the chamber, bullet damage, and the potential for an explosion if the bullet becomes stuck.[8]

The shock of firing can exert a great deal of stress on the crane, as in most designs the cylinder is only held closed at one point, the rear of the cylinder. Stronger designs, such as the Ruger Super Redhawk, use a lock in the crane as well as the lock at the rear of the cylinder. This latch provides a more secure bond between cylinder and frame, and allows the use of larger, more powerful cartridges. Swing-out cylinders are rather strong, but not as strong as fixed cylinders, and great care must be taken with the cylinder when loading, so as not to damage the crane.[8]

History

Background

Firearm cylinders were first developed in the 16th century and, over time, had anywhere from three to twelve chambers bored into them.[9] One of the earliest examples is dated 1587.[10] Cylinders were developed as a device to increase the multiple-fire capability of firearms. Firearms of the period were mostly muskets and only capable of firing a single shot before needing to be reloaded. Reloading the single-shot firearm was time-consuming and in a military or self-defense situation where seconds mattered, this rendered it almost useless after the first shot. A firearm with several pre-loaded chambers would naturally increase its effectiveness against an enemy.

Snaphance and flintlock

The first firearms to incorporate a cylinder were the snaphance and flintlock types. The lock mechanisms were very similar and used the same type of cylinder. The chambers did not penetrate completely through the cylinder. The back of each chamber had a small touch hole drilled through the side of the cylinder. For each touch hole, a small flash pan was created at the cylinder's surface. Each pan with touch hole had a sliding gate to cover it. This prevented the gunpowder from falling out as the cylinder was turned. Assuming that each pan was filled with powder and that each chamber was charged, the operator manually turned the cylinder to align a chamber with the barrel, opened the pan cover, and was then ready to fire. Compared to the single-fire musket, the manufacturing process for this type of firearm was very expensive, which kept their numbers fairly low.

Percussion

The next evolution of the cylinder did not occur until the 1830s. While chemistry was still in its infancy, the development of fulminates as primers for firearm ignition contributed to the invention of the percussion cap. This, in turn, led to the development of the percussion cylinder. As with the earlier flintlock cylinders, the chambers within the percussion cylinders were not bored completely through. Percussion caps replaced the flintlock pans as primers and the drilled touch holes were incorporated within nipples. The nipples were inserted into a recess at the rear of each chamber. The percussion cap was placed over the nipple. These arms quickly incorporated mechanisms that automatically rotated the cylinder, aligning the chamber with the barrel, and locking it in place. Each chamber was loaded in a similar manner as the previous flintlocks, that is, from the front of the cylinder, powder was poured into the chamber and then a bullet was inserted and pressed into place with a ramrod.

Needle-fire revolver

After the initial invention in the late 1830s of a needle-fire rifle, a revolver was soon developed. This type of firearm used a paper cartridge.[11] It used a long, thin, needle-like firing pin that passed through a small hole at the rear of the cylinder, through the powder, and struck a disposable primer cap that was set behind the bullet. The revolver's cylinder simply had a small hole drilled at the rear of each chamber.[12] The use of a paper cartridge was a change from the earlier method of charging a firearm.

Pin-fire

At approximately the same time that the needle-fire system was developed, a pin-fire method was also developed. This method originally used a paper cartridge with a primer cap within a brass base, which quickly evolved into an all-brass cartridge. From the side, a stout pin was inserted into the cartridge above the cap. The gun's hammer pushed the pin into the cap and set off the primer. A revolver using this method had a cylinder with chambers that were bored completely through with a slight channel where the pin rested.[13] This type of cylinder was first patented in France in 1854.[14] Loading these revolvers was accomplished by moving a loading gate that was mounted behind the cylinder. To remove the spent cartridges, a push-rod was used to back the cartridges out of the cylinder through the loading gate.

Rimfire and centerfire

Cylinders that use these cartridges are what most people envision as modern cylinders. These cartridges are all metallic and are struck at the rear by the hammer. The rimfire cartridges contain a primer around the inside of the rim. The centerfire cartridges have a primer cap pressed into the base. They are similar to the pin-fire cylinders as the chambers are bored completely through, but they have no additional holes or channels connected to the chambers. In 1857, Smith & Wesson held the patent for this bored through cylinder.[15] Removal of cartridges from the early models was done one at a time with a push rod as in the pin-fire cylinders. Later models that had swing-out cylinders incorporated push rods with extractors that pushed all of the cartridges out in a single operation.

Tape-primer

In the 1850s, in competition with Colt's percussion revolvers, a revolver was developed that used a paper tape primer to ignite the powder in the chambers. This worked much as today's toy cap pistols.[16] This basically worked the same as a percussion revolver, but with only one nipple that sent the ignition spark to a flash hole at the rear of each chamber. Each chamber was loaded in the same manner as the percussion revolvers.

See also

References

- ^ Ramage, Ken; Sigler, Derrek (2008). Guns Illustrated 2009. Iola, Wisconsin: F+W Media, Inc. p. 133. ISBN 0-89689-673-0.

- ^ Herring, Hal (2008). Famous Firearms of the Old West: From Wild Bill Hickok's Colt Revolvers to Geronimo's Winchester, Twelve Guns That Shaped Our History. Globe Pequot Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-7627-4508-1.

- ^ Radielovic, Marko; Prasac, Max (2012). Big-Bore Revolvers. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. p. 17. ISBN 1-4402-2856-6.

- ^ Taffin, John (2005). Kevin Michalowski (ed.). The Gun Digest Book of Cowboy Action Shooting: Guns Gear Tactics. Gun Digest Books. pp. 173–175. ISBN 0-89689-140-2.

- ^ Campbell, R. K. (December 2011). The Complete Illustrated Manual of Handgun Skills. Zenith Imprint. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-61059-745-6. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ TaFFIN, John (28 September 2005). Single Action Sixguns. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-4402-2694-6.

- ^ Tilstone, William J.; Savage, Kathleen A.; Clark, Leigh A. (1 January 2006). Forensic Science: An Encyclopedia of History, Methods, and Techniques. ABC-CLIO. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-1-57607-194-6.

- ^ a b Sweeney, Patrick (2009). Gunsmithing - Pistols and Revolvers. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. pp. 49–50. ISBN 1-4402-0389-X.

- ^ Blair, Claude, ed., Pollard’s History of Firearms (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1983), 210.

- ^ Hogg, Ian V. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Firearms: Military and civil firearms from the beginnings to the present day ... (London: New Burlington Books, 1980), 40.

- ^ Friedel, Robert. A Culture of Improvement (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2007), 371.

- ^ Myatt, Frederick. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pistols & Revolvers: An Illustrated History of Handguns from the 16th Century to the Present Day (New York: Crescent Books, 1980), 66.

- ^ Myatt, Frederick. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pistols & Revolvers: An Illustrated History of Handguns from the 16th Century to the Present Day (New York: Crescent Books, 1980), 88-91.

- ^ Batchelor, John and John Walter. Handgun: From matchlock to laser-sighted weapon (Portugal: Talos Books, 1988), 78.

- ^ Myatt, Frederick. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pistols & Revolvers: An Illustrated History of Handguns from the 16th Century to the Present Day (New York: Crescent Books, 1980), 84.

- ^ Myatt, Frederick. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pistols & Revolvers: An Illustrated History of Handguns from the 16th Century to the Present Day (New York: Crescent Books, 1980), 67.

Sources

- Batchelor, John and John Walter. Handgun: From matchlock to laser-sighted weapon (Portugal: Talos Books, 1988).

- Blair, Claude, ed., Pollard’s History of Firearms (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1983).

- Friedel, Robert. A Culture of Improvement (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2007).

- Hogg, Ian V. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Firearms: Military and civil firearms from the beginnings to the present day. . . (London: New Burlington Books, 1980).

- Myatt, Frederick. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pistols & Revolvers: An Illustrated History of Handguns from the 16th Century to the Present Day (New York: Crescent Books, 1980).