Embargo Act of 1807

| |

| Long title | An Act laying an Embargo on all ships and vessels in the ports and harbors of the United States. |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 10th United States Congress |

| Effective | December 23, 1807 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub. L. 10–5 |

| Statutes at Large | 2 Stat. 451, Chap. 5 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| Repealed by Non-Intercourse Act § 19 | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Early life and political career

3rd President of the United States

First term

Second term

Post-presidency

Legacy

|

||

| Origins of the War of 1812 |

|---|

The Embargo Act of 1807 was a general trade embargo on all foreign nations that was enacted by the United States Congress. As a successor or replacement law for the 1806 Non-importation Act and passed as the Napoleonic Wars continued, it represented an escalation of attempts to persuade Britain to stop any impressment of American sailors and to respect American sovereignty and neutrality but also attempted to pressure France and other nations in the pursuit of general diplomatic and economic leverage.

In the first decade of the 19th century, American shipping grew. During the Napoleonic Wars, rival nations Britain and France targeted neutral American shipping as a means of disrupting the trade of the other nation. American merchantmen who were trading with "enemy nations" were seized as contraband of war by European navies. The British Royal Navy had impressed American sailors who had either been British-born or previously served on British ships, even if they now claimed to be American citizens with American papers. Incidents such as the Chesapeake–Leopard affair outraged Americans.

Congress imposed the embargo in direct response to these events. President Thomas Jefferson acted with restraint, weighed public support for retaliation, and recognized that the United States was militarily far weaker than either Britain or France. He recommended that Congress respond with commercial warfare, a policy that appealed to Jefferson both for being experimental and for foreseeably harming his domestic political opponents more than his allies, whatever its effect on the European belligerents. The 10th Congress was controlled by his allies and agreed to the Act, which was signed into law on December 22, 1807.

In terms of diplomacy, the Embargo failed to improve the American diplomatic position, and sharply increased international political tensions. Both widespread evasion of the embargo and loopholes in the legislation reduced its impact on its targets. British commercial shipping, which already dominated global trade, was successfully adapting to Napoleon's Continental System by pursuing new markets, particularly in the restive Spanish and Portuguese colonies in South America. Thus, British merchants were well-positioned to grow at American expense when the embargo sharply reduced American trade activity.

The Act's prohibition on imports stimulated the growth of nascent US domestic industries across the board, particularly the textile industry, and marked the beginning of the manufacturing system in the United States, reducing the nation's dependence upon imported manufactured goods.[1]

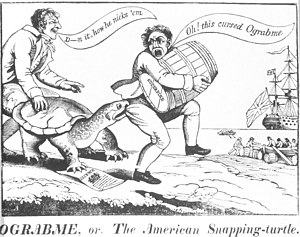

Americans opposed to the Act launched bitter protests, particularly in New England commercial centers. Support for the declining Federalist Party, which intensely opposed Jefferson, temporarily rebounded and drove electoral gains in 1808 (Senate and House). In the waning days of Jefferson's presidency, the Non-Intercourse Act lifted all embargoes on American shipping except for cargos bound for British or French ports. Enacted on March 1, 1809, it exacerbated tensions with Britain and eventually led to the War of 1812.

Background

[edit]After a short truce between the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars during 1802–1803, the European conflicts resumed and continued until the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1814.[2] The wars caused American relations with both Britain and France to deteriorate rapidly. There was grave risk of war with one or the other. With Britain supreme on the sea and France on the land, the war developed into a struggle of blockade and counterblockade. The commercial war peaked in 1806 and 1807. Britain's Royal Navy shut down most European harbors to American ships unless they first traded through British ports. France declared a paper blockade of Britain but lacked a navy that could enforce it and seized American ships that obeyed British regulations. The Royal Navy needed large numbers of sailors, and was deeply angered at the American merchant fleet for being a haven for British deserters.[3]

British impressment of American sailors humiliated the United States, which showed it to be unable to protect its ships and their sailors.[4] The British practice of taking British deserters, many of them now American citizens, from American ships and conscripting them into the Royal Navy increased greatly after 1803, and it caused bitter anger in the United States.

On June 21, 1807, an American warship, the USS Chesapeake, was boarded on the high seas off the coast of Norfolk, Virginia[5] by a British warship, HMS Leopard. The Chesapeake had been carrying four deserters from the Royal Navy, three of them American and one British. The four deserters, who had been issued American papers, were removed from the Chesapeake and taken to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where the lone Briton was hanged while the three Americans were initially sentenced to 500 lashes. (American diplomatic pressure led to the return of the three Americans, without the dispensing of punishment.) The outraged nation demanded action, and President Jefferson ordered all British ships out of American waters.[6]

Initial legislation

[edit]Passed on December 22, 1807, the Act did the following:[7]

- An embargo was laid on all ships and vessels under US jurisdiction.

- All ships and vessels were prevented from obtaining clearance to undertake in voyages to foreign ports or places.

- The US President was allowed to make exceptions for ships under his immediate direction.

- The President was authorized to enforce via instructions to revenue officers and the Navy.

- It was not constructed to prevent the departure of any foreign ship or vessel, with or without cargo on board,

- A bond or surety was required from merchant ships on a voyage between US ports.

- Warships were exempted from the embargo provisions.

The shipping embargo was a cumulative addition to the Non-importation Act of 1806 (2 Stat. 379), which was a "Prohibition of the Importation of certain Goods and Merchandise from the Kingdom of Great Britain," the prohibited imported goods being defined where their chief value, which consists of leather, silk, hemp or flax, tin or brass, wool, glass, and paper goods, nails, hats, clothing, and beer.[8]

The Embargo Act of 1807 was codified at 2 Stat. 451 and formally titled "An Embargo laid on Ships and Vessels in the Ports and Harbours of the United States". The bill was drafted at the request of President Thomas Jefferson and was passed by the 10th Congress on December 22, 1807, during Session 1; Chapter 5. Congress initially acted to enforce a bill prohibiting only imports, but supplements to the bill eventually banned exports as well.

Impact on US trade

[edit]

The embargo had the dual effect of severely curtailing American overseas trade, while forcing industrial concerns to invest new capital into domestic manufacturing in the United States.[9] In commercial New England and the Middle Atlantic, ships sat idle. In agricultural areas, particularly the South, farmers and planters could not sell crops internationally. The scarcity of European goods stimulated American manufacturing, particularly in the North, and textile manufacturers began to make massive investments in cotton mills.[9] However, as Britain was still able to export to America particularly through Canada, that benefit did not immediately compensate for present loss of trade and economic momentum.[10] A 2005 study by the economic historian Douglas Irwin estimates that the embargo cost about 5% of America's 1807 gross national product.[11]

Miniature engraved teapots were manufactured to bolster flagging popular support for the Embargo Act. The slogans on the teapots were intended to reinforce the principles driving the government's ongoing embargo against Britain and France.[citation needed]

Case studies

[edit]A case study of Rhode Island shows the embargo to have devastated shipping-related industries, wrecked existing markets, and caused an increase in opposition to the Democratic–Republican Party. Smuggling was widely endorsed by the public, which viewed the embargo as a violation of its rights. Public outcry continued and helped the Federalists regain control of the state government in 1808–1809. The case is a rare example of American national foreign policy altering local patterns of political allegiance.

Despite its unpopular nature, the Embargo Act had some limited unintended benefits to the Northeast, especially by driving capital and labor into New England textile and other manufacturing industries, which lessened America's reliance on British trade.[12]

In Vermont, the embargo was doomed to failure on the Lake Champlain–Richeleiu River water route because of the state's dependence on a Canadian outlet for produce. At St. John, Lower Canada, £140,000 worth of goods smuggled by water were recorded there in 1808, a 31% increase over 1807. Shipments of ashes to make soap nearly doubled to £54,000, but those of lumber dropped by 23% to £11,200. Manufactured goods, which had expanded to £50,000 since Jay's Treaty in 1795, fell by over 20%, especially articles made near tidewater. Newspapers and manuscripts recorded more lake activity than usual, despite the theoretical reduction in shipping that should accompany an embargo. The smuggling was not restricted to water routes, as herds were readily driven across the uncontrollable land border. Southbound commerce gained two thirds overall, but furs dropped a third. Customs officials maintained a stance of vigorous enforcement throughout, and Gallatin's Enforcement Act (1809) was a party issue. Many Vermonters preferred the embargo's exciting game of revenuers versus smugglers, which brought high profits, versus mundane, low-profit normal trade.[13]

The New England merchants who evaded the embargo were imaginative, daring, and versatile in their violation of federal law. Gordinier (2001) examines how the merchants of New London, Connecticut, organized and managed the cargoes purchased and sold and the vessels that were used during the years before, during, and after the embargo. Trade routes and cargoes, both foreign and domestic, along with the vessel types, and the ways that their ownership and management were organized show the merchants of southeastern Connecticut evinced versatility in the face of crisis.[14]

Gordinier (2001) concludes that the versatile merchants sought alternative strategies for their commerce and, to a lesser extent, for their navigation. They tried extralegal activities, a reduction in the size of the foreign fleet, and the redocumentation of foreign trading vessels into domestic carriage. Most importantly, they sought new domestic trading partners and took advantage of the political power of Jedidiah Huntington, the Customs Collector. Huntington was an influential member of the Connecticut leadership class (called "the Standing Order") and allowed scores of embargoed vessels to depart for foreign ports under the guise of "special permission". Old modes of sharing vessel ownership to share the risk proved to be difficult to modify. Instead, established relationships continued through the embargo crisis despite numerous bankruptcies.[14]

Enforcement efforts

[edit]Jefferson's Secretary of the Treasury, Albert Gallatin, was against the entire embargo and foresaw correctly the impossibility of enforcing the policy and the negative public reaction. "As to the hope that it may... induce England to treat us better," wrote Gallatin to Jefferson shortly after the bill had become law, "I think is entirely groundless... government prohibitions do always more mischief than had been calculated; and it is not without much hesitation that a statesman should hazard to regulate the concerns of individuals as if he could do it better than themselves."[15]: 368

Since the bill hindered US ships from leaving American ports bound for foreign trade, it had the side effect of hindering American exploration.

First supplementary act

[edit]Just weeks later, on January 8, 1808, legislation again passed the 10th Congress, Session 1; Chapter 8: "An Act supplementary..." to the Embargo Act (2 Stat. 453). As the historian Forrest McDonald wrote, "A loophole had been discovered" in the initial enactment, "namely that coasting vessels, and fishing and whaling boats" had been exempt from the embargo, and they had been circumventing it, primarily via Canada. The supplementary act extended the bonding provision (Section 2 of the initial Embargo Act) to those of purely-domestic trades:[16]

- Sections 1 and 2 of the supplementary act required bonding to coasting, fishing, and whaling ships and vessels. Even river boats had to post a bond.

- Section 3 made violations of either the initial or supplementary act an offense. Failure of the shipowner to comply would result in forfeiture of the ship and its cargo or a fine of double that value and the denial of credit for use in custom duties. A captain failing to comply would be fined between one and twenty thousand dollars and would forfeit the ability to swear an oath before any customs officer.

- Section 4 removed the warship exemption from applying to privateers or vessels with a letter of marque.

- Section 5 established a fine for foreign ships loading merchandise for export and allowed for its seizure.

Meanwhile, Jefferson requested authorization from Congress to raise 30,000 troops from the current standing army of 2,800, but Congress refused. With their harbors for the most part unusable in the winter anyway, New England and the northern ports of the mid-Atlantic states had paid little notice to the previous embargo acts. That was to change with the spring thaw and the passing of yet another embargo act.[15]: 147

With the coming of the spring, the effect of the previous acts were immediately felt throughout the coastal states, especially in New England. An economic downturn turned into a depression and caused increasing unemployment. Protests occurred up and down the eastern coast. Most merchants and shippers simply ignored the laws. On the Canada–United States border, especially in Upstate New York and in Vermont, the embargo laws were openly flouted. Federal officials believed parts of Maine, such as Passamaquoddy Bay on the border with the British territory of New Brunswick, were in open rebellion. By March, an increasingly-frustrated Jefferson had become resolved to enforce the embargo to the letter.[citation needed]

Other supplements to Act

[edit]On March 12, 1808, Congress passed and Jefferson signed into law yet another supplement to the Embargo Act. It[17] prohibited for the first time all exports of any goods, whether by land or by sea. Violators were subject to a fine of $10,000, plus forfeiture of goods, per offense. It granted the President broad discretionary authority to enforce, deny, or grant exceptions to the embargo.[15]: 144 Port authorities were authorized to seize cargoes without a warrant and to try any shipper or merchant who was thought to have merely contemplated violating the embargo.

Despite the added penalties, citizens and shippers openly ignored the embargo. Protests continued to grow and so the Jefferson administration requested and Congress rendered yet another embargo act.

Consequences

[edit]

The immediate effect of the embargo hurt the United States as much as it did Britain and France. Britain, expecting to suffer most from the American regulations, built up a new South American market for its exports, and the British shipowners were pleased that American competition had been removed by the action of the US government.

Jefferson placed himself in a strange position with his embargo policy. Though he had frequently argued for as little government intervention as possible, he now found himself assuming extraordinary powers in an attempt to enforce his policy. The presidential election of 1808 had James Madison defeat Charles Cotesworth Pinckney but showed that the Federalists were regaining strength and helped to convince Jefferson and Madison that the embargo should end.[18] Shortly before leaving office in March 1809, Jefferson signed the repeal of the embargo.

Despite its unpopular nature, the Embargo Act had one longterm positive impact. Unfulfilled domestic demand for manufactured goods stimulated the growth of the Industrial Revolution in the United States, resulting in an emerging American domestic manufacturing system.[1][12][19][9]

Repeal

[edit]On March 1, 1809, Congress passed the Non-Intercourse Act. The law enabled the President, once the wars of Europe had ended, to declare the country sufficiently safe and to allow foreign trade with certain nations.[20]

In 1810, the government was ready to try yet another tactic of economic coercion, the desperate measure known as Macon's Bill Number 2.[21] The bill became law on May 1, 1810, and replaced the Non-Intercourse Act. It was an acknowledgment of the failure of economic pressure to coerce the European powers. Trade with both Britain and France was now thrown open, and the US attempted to bargain with the two belligerents. If either power removed its restrictions on American commerce, the US would reapply non-intercourse against the power that had not done so.

Napoleon quickly took advantage of that opportunity. He promised that his Berlin and Milan Decrees would be repealed, and Madison reinstated non-intercourse against Britain in the fall of 1810. Though Napoleon did not fulfill his promise, the strained Anglo-American relations prevented him from being brought to task for his duplicity.[22]

The attempts of Jefferson and Madison to secure recognition of American neutrality via peaceful means gained a belated success in June 1812, when Britain finally promised to repeal their 1807 Orders in Council. The British concession was too late since when the news had reached America, the United States had already declared the War of 1812 against Britain.

Subsequent Wartime legislation

[edit]America's declaration of war in mid-June 1812 was followed shortly by the Enemy Trade Act of 1812 on July 6, which employed similar restrictions as previous legislation.[23] it was likewise ineffective and tightened in December 1813 and debated for further tightening in December 1814. After existing embargoes expired with the onset of war, the Embargo Act of 1813 was signed into law December 17, 1813.[24] Four new restrictions were included: an embargo prohibiting all American ships and goods from leaving port, a complete ban on certain commodities customarily produced in the British Empire, a ban against foreign ships trading in American ports unless 75% of the crew were citizens of the ship's flag, and a ban on ransoming ships. The Embargo of 1813 was the nation's last great trade restriction. Never again would the US government cut off all trade to achieve a foreign policy objective.[25] The Act particularly hurt the Northeast since the British kept a tighter blockade on the South and thus encouraged American opposition to the administration. To make his point, the Act was not lifted by Madison until after the defeat of Napoleon, and the point was moot.

On February 15, 1815, Madison signed the Enemy Trade Act of 1815,[26] which was tighter than any previous trade restriction including the Enforcement Act of 1809 (January 9) and the Embargo of 1813, but it would expire two weeks later when official word of peace from Ghent was received.[27][28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b [1] Smith, Ryan P., 'A History of America’s Ever-Shifting Stance on Tariffs: Unpacking a debate as old as the United States itself', Smithsonian Magazine, 18 April 2018, retrieved 5 April 2023

- ^ Napoleon's brief return during the "Hundred Days" had no bearing on the United States.

- ^ DeToy, Brian (1998). "The Impressment of American Seamen during the Napoleonic Wars". Consortium on Revolutionary Europe 1750–1850: Selected Papers, 1998. Florida State University. pp. 492–501.

- ^ Gilje, Paul A. (Spring 2010). "'Free Trade and Sailors' Rights': The Rhetoric of the War of 1812". Journal of the Early Republic. 30 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1353/jer.0.0130. S2CID 145098188.

- ^ "Embargo of 1807". Monticello and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved December 18, 2015.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C.; Reuter, Frank T. (1996). Injured Honor: The Chesapeake-Leopard Affair. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-824-0.

- ^ 2 Stat. 451 (1807) Archived April 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine Library of Congress, U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875

- ^ 2 Stat. 379 (1806) Archived April 5, 2023, at the Wayback Machine Library of Congress, U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875

- ^ a b c [2] Rantakari, Heikki, 'The Antebellum Tariff on Cotton Textiles 1816-1860: Consolidation', 4 April 2003, retrieved 5 April 2023

- ^ Malone, Dumas (1974). Jefferson the President: The Second Term. Boston: Brown-Little. ISBN 0-316-54465-5.

- ^ Irwin, Douglas (September 2005). "The Welfare Cost of Autarky: Evidence from the Jeffersonian Trade Embargo, 1807–09" (PDF). Review of International Economics. 13 (4): 631–645. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9396.2005.00527.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 24, 2018. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ a b Strum, Harvey (May 1994). "Rhode Island and the Embargo of 1807" (PDF). Rhode Island History. 52 (2): 58–67. ISSN 0035-4619.

Although the state's manufacturers benefited from the embargo, taking advantage of the increased demand for domestically produced goods (especially cotton products), and merchants with idle capital were able to move from shipping and trade into manufacturing, this industrial growth did not compensate for the considerable distress that the embargo caused.

- ^ Muller, H. Nicholas III (Winter 1970). "Smuggling into Canada: How the Champlain Valley Defied Jefferson's Embargo" (PDF). Vermont History. 38 (1): 5–21.

- ^ a b Gordinier, Glenn Stine (January 2001). Versatility in Crisis: The Merchants of the New London Customs District Respond to the Embargo of 1807–1809 (PhD dissertation). U. of Connecticut. AAI3004842.

- ^ a b c Adams, Henry (1879). Gallatin to Jefferson, December 1807. The Writings of Albert Gallatin. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

- ^ 2 Stat. 453 (1808) Library of Congress, U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875

- ^ "Statutes at Large: Congress 10 | Law Library of Congress". www.loc.gov. September 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ^ Tucker, Robert W.; Hendrickson, David C. (1990). "Chapter 20". Empire of Liberty: The Statecraft of Thomas Jefferson. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506207-8.

- ^ Frankel, Jeffrey A. (June 1982). "The 1807–1809 Embargo Against Great Britain". Journal of Economic History. 42 (2): 291–308. doi:10.1017/S0022050700027443. JSTOR 2120129. S2CID 154647613.

- ^ Heidler, David Stephen; Heidler, Jeanne T., eds. (2004). Encyclopedia of the War of 1812. Naval Institute Press. pp. 390–391. ISBN 978-1-591-14362-8.

- ^ Wills, Garry (2002). James Madison: The 4th President, 1809–1817. The American Presidents Series. Vol. 4. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-8050-6905-1.

- ^ Merrill, Dennis; Paterson, Thomas (2009). Major Problems in American Foreign Relations: To 1920. Cengage Learning. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0-547-21824-3. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ "Enemy Trade Act of 1812 ~ P.L. 12-129" (PDF). 2 Stat. 778 ~ Chapter CXXIX. USLaw.Link. July 6, 1812.

- ^ "Embargo Act of 1813 ~ P.L. 13-1" (PDF). 3 Stat. 88 ~ Chapter I. USLaw.Link. December 17, 1813.

- ^ Hickey, Donald R. (1989). "Ch.7: The Last Embargo". The War of 1812 – A Forgotten Conflict. University of Illinois Press. pp. 172, 181. ISBN 9780252060595.

- ^ "Enemy Trade Act of 1815 ~ P.L. 13-31" (PDF). 3 Stat. 195 ~ Chapter XXXI. USLaw.Link. February 4, 1815.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C.; Arnold, James R., eds. (2012). The Encyclopedia Of the War Of 1812, a political, social, and military history. ABC-CLIO. pp. 221–25. ISBN 978-1-85109-956-6.

- ^ "Enforcement Act of 1809 ~ P.L. 10-5" (PDF). 2 Stat. 506 ~ Chapter V. USLaw.Link. January 9, 1809.

Further reading

[edit]- Hofstadter, Richard. 1948. The American Political Tradition (Chapter 11) Alfred A. Knopf. in Essays on the Early Republic, 1789–1815 Leonard Levy, Editor. Dryden Press, 1974.

- Irwin, Douglas A. (2005). "The Welfare Cost of Autarky: Evidence from the Jeffersonian Trade Embargo, 1807–09" (PDF). Review of International Economics. 13 (4): 631–45. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9396.2005.00527.x.

- Kaplan, Lawrence S. (1957). "Jefferson, the Napoleonic Wars, and the Balance of Power". William and Mary Quarterly. 14 (2): 196–217. doi:10.2307/1922110. JSTOR 1922110. in Essays on the Early Republic, 1789–1815 Leonard Levy, Editor. Dryden Press, 1974.

- Levy, Leonard W. (1963). Jefferson and Civil Liberties: The Darker Side. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

- Levy, Leonard. 1974. Essays on the Early Republic, 1789–1815. Dryden Press, 1974.

- McDonald, Forrest (1976). The Presidency of Thomas Jefferson. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0147-3.

- Malone, Dumas (1974). Jefferson the President: The Second Term. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-316-54465-5.

- Mannix, Richard (1979). "Gallatin, Jefferson, and the Embargo of 1808". Diplomatic History. 3 (2): 151–72. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.1979.tb00307.x.

- Muller, H. Nicholas (1970). "Smuggling into Canada: How the Champlain Valley Defied Jefferson's Embargo". Vermont History. 38 (1): 5–21. ISSN 0042-4161.

- Perkins, Bradford. 1968. Embargo: Alternative to War (Chapter 8 from Prologue to War: England and the United States, 1805–1812, University of California Press, 1968) in Essays on the Early Republic 1789–1815. Leonard Levy, Editor. Dryden Press, 1974.

- [3] Rantakari, Heikki, 'The Antebellum Tariff on Cotton Textiles 1816-1860: Consolidation', 4 April 2003, retrieved 5 April 2023

- Sears, Louis Martin (1927). Jefferson and the Embargo. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Smelser, Marshall (1968). The Democratic Republic, 1801–1815. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-131406-4.

- Smith, Joshua M. (1998). "'So Far Distant from the Eyes of Authority:' Jefferson's Embargo and the U.S. Navy, 1807–1809". In Symonds, Craig (ed.). New Interpretations in Naval History: Selected Papers from the Twelfth Naval History Symposium. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. pp. 123–40. ISBN 1-55750-624-8.

- Smith, Joshua M. (2000). "Murder on Isle au Haut: Violence and Jefferson's Embargo in Coastal Maine, 1808–1809". Maine History. 39 (1): 17–40.

- Smith, Joshua M. (2006). Borderland Smuggling: Patriots, Loyalists, and Illicit Trade in the Northeast, 1783–1820. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2986-4.

- Spivak, Burton (1979). Jefferson's English Crisis: Commerce, Embargo, and the Republican Revolution. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 0-8139-0805-1.

- Strum, Harvey (1994). "Rhode Island and the Embargo of 1807". Rhode Island History. 52 (2): 58–67. ISSN 0035-4619.

External links

[edit]- The Embargo Act of 1807 (James Schouler, The Great Republic by the Master Historians Vol. II, Hubert H. Bancroft and Oliver H. G. Leigh, Ed. (1902)[1897], pp. 335–364)

- 1807 in American law

- 10th United States Congress

- 1807 in economic history

- December 1807 events

- Embargoes

- France–United States relations

- History of foreign trade of the United States

- War of 1812 legislation

- Presidency of Thomas Jefferson

- United Kingdom–United States relations

- United States federal trade legislation