Dunhuang

Dunhuang

敦煌 | |

|---|---|

County-level city | |

敦煌市 | |

Dunhuang market | |

Dunhuang City (red) in Jiuquan City (yellow) and Gansu | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Province | Gansu |

| Prefecture-level city | Jiuquan |

| Elevation | 1,142 m (3,747 ft) |

| Population (2000) | |

| • Total | 187,578 |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (CST) |

ⓘ (Chinese: 敦煌; pinyin: Dūnhuáng, also as simplified Chinese: 炖煌; traditional Chinese: 燉煌; pinyin: Dūnhuáng in ancient times meaning 'Blazing Beacon') is a county-level city (pop. 187,578 (2000)) in northwestern Gansu province, Western China. It was a major stop on the ancient Silk Road. It was also known at times as Shāzhōu (沙州), or 'City of Sands',[1] "or Dukhan as the Turkis call it."[2] It is best known for the nearby Dunhuang Caves.

Administratively, the county-level city of Dunhuang is part of the prefecture-level city of Jiuquan.

It is situated in a rich oasis containing Crescent Lake and Mingsha Shan (鸣沙山, literally "Echoing-Sand Mountain"). Mingsha Shan is named after the sound of the wind whipping off the dunes, the singing sand phenomenon.

It commands a strategic position at the crossroads of the ancient Southern Silk Route and the main road leading from India via Lhasa to Mongolia and Southern Siberia,[1] as well as controlling the entrance to the narrow Hexi Corridor which led straight to the heart of the north Chinese plains and the ancient capitals of Chang'an (today known as Xi'an) and Luoyang.[3]

History

There is evidence of human habitation in the Dunhuang area as early as 2,000 BC, possibly by people recorded as the Qiang in Chinese history. Its name was also mentioned as part of the homeland of the Yuezhi in the Records of the Grand Historian, although some have argued that this may refer to an unrelated toponym, Dunhong. By the third century BC, the area became dominated by the Xiongnu, but came under Chinese rule during the Han Dynasty after Emperor Wu defeated the Xiongnu in 121 BC.

Dunhuang was one of the four frontier garrison towns (along with Jiuquan, Zhangye and Wuwei) established by the Emperor Wu after the defeat of Xiongnu, and the Chinese built fortifications at Dunhuang and sent settlers there. The name Dunhuang, or Blazing Beacon, refers to the beacons lit to warn of attacks by marauding nomadic tribes. Dunhuang Commandery was probably established shortly after 104 BC.[4] Located in the western end of the Hexi Corridor near the historic junction of the Northern and Southern Silk Roads, Dunhuang was a town of military importance.[5]

"The Great Wall was extended to Dunhuang, and a line of fortified beacon towers stretched westwards into the desert. By the second century AD Dunhuang had a population of more than 76,000 and was a key supply base for caravans that passed through the city: those setting out for the arduous trek across the desert loaded up with water and food supplies, and others arriving from the west gratefully looked upon the mirage-like sight of Dunhuang's walls, which signified safety and comfort. Dunhuang prospered on the heavy flow of traffic. The first Buddhist caves in the Dunhuang area were hewn in 353."[6]

During the time of the Sixteen Kingdoms, Li Gao established the Western Liang here in 400 AD. In 405 the capital of the Western Liang was moved from Dunhuang to Jiuquan. In 421 the Western Liang was conquered by the Northern Liang.

In later centuries, during the Sui and Tang dynasties, it was a major point of communication between ancient China and Central Asia. By the Tang Dynasty it became the major hub of commerce of the Silk Road. Early Buddhist monks arrived at Dunhuang via the ancient Northern Silk Road, the northernmost route of about 2,600 kilometres (1,600 mi) in length, which connected the ancient Chinese capital of Xi'an westward over the Wushao Ling Pass to Wuwei and on to Kashgar.[7] For centuries, Buddhist monks at Dunhuang collected scriptures from the West, and many pilgrims passed through the area, painting murals inside the Mogao Caves or "Caves of a Thousand Buddhas."[8] A small number of Christian artifacts have also been found in the caves (see Jesus Sutras), testimony to the wide variety of people who made their way along the Silk Road.

As a frontier town, Dunhuang was fought over and occupied at various times by non-Han Chinese people. After the fall of Han Dynasty it was under the rule of various nomadic tribes such as the Xiongnu during Northern Liang and the Turkic Tuoba during Northern Wei. The Tibetans occupied Dunhuang when the Tang empire became weakened considerably after the An Lushan Rebellion; and even though it was later returned to Tang rule, it was under quasi-autonomous rule by the local general Zhang Yichao who expelled the Tibetans in 848. After the fall of Tang, Zhang's family formed the Kingdom of Golden Mountain in 910, and was then succeeded by the Cao family who formed alliances with the Uighurs and the Kingdom of Khotan. During the Song Dynasty, Dunhuang fell outside the Chinese borders. In 1037 it came under the rule of Shazhou Uighurs, then in 1068 the Tanguts who founded the Xi Xia Dyansty. It was conquered in 1227 by the Mongols who sacked and destroyed the town, and the rebuilt town became part of China again when Kublai Khan conquered the rest of China. Dunhuang went into a steep decline after the Chinese trade with the outside world became dominated by Southern sea-routes, and the Silk Road was officially abandoned during the Ming Dynasty. It was occupied again by the Tibetans in 1516, but retaken by China two centuries later ca. 1715 during the Qing Dynasty.[9]

Today, the site is an important tourist attraction and the subject of an ongoing archaeological project. A large number of manuscripts and artifacts retrieved at Dunhuang have been digitized and made publicly available via the International Dunhuang Project.[10] The expansion of the Kumtag Desert, which is resulting from long-standing overgrazing of surrounding lands, has reached the edges of the city.[11]

In 2011 satellite images showing huge structures in the desert near Dunhuang surfaced online and caused a brief media stir.[12]

Climate

Dunhuang, being surrounded by high mountains, has an arid, continental climate. The annual average temperature is 9.48 °C (49.1 °F), but the monthly daily mean temperature ranges from 24.6 °C (76.3 °F) in July down to −8.3 °C (17.1 °F) in January. The city is extremely hot in summer and cold in winter, and usually has sharp temperature differences between day and night. Precipitation occurs only in trace amounts and quickly evaporates.[13]

| Climate data for Dunhuang (1971−2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −0.8 (30.6) |

4.9 (40.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.7 (90.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

26.8 (80.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −14.6 (5.7) |

−10.5 (13.1) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

4.1 (39.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.4 (61.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

8.5 (47.3) |

0.6 (33.1) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−12 (10.4) |

1.8 (35.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.8 (0.03) |

0.8 (0.03) |

2.1 (0.08) |

2.4 (0.09) |

2.4 (0.09) |

8.0 (0.31) |

15.2 (0.60) |

6.3 (0.25) |

1.5 (0.06) |

0.8 (0.03) |

1.3 (0.05) |

0.8 (0.03) |

42.4 (1.65) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 4.8 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 21.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 52 | 40 | 35 | 31 | 33 | 42 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 51 | 55 | 43 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 219.0 | 218.6 | 254.9 | 282.4 | 320.2 | 313.6 | 318.9 | 316.1 | 296.1 | 280.8 | 230.4 | 206.8 | 3,257.8 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration | |||||||||||||

Culture

Buddhist caves

A number of Buddhist cave sites are located in the Dunhuang area, the most important of these is the Mogao Caves which is located 25 km (16 mi) southwest of Dunhuang. There are 735 caves in Mogao, and the caves in Mogao are particularly noted for their Buddhist art as well as the hoard of manuscripts, the Dunhuang manuscripts, found hidden in a sealed-up cave.

Numerous smaller Buddhist cave sites are located in the region, including the Western Thousand Buddha Caves, the Eastern Thousands Buddha Caves, and the Five Temple site. The Yulin Caves are located further east in Guazhou County.

Other historical sites

- Crescent Lake

- The Yumen Pass, built in 111 BC, located 90 km (56 mi) northwest of Dunhuang in the Gobi desert.

- The Yangguan Pass

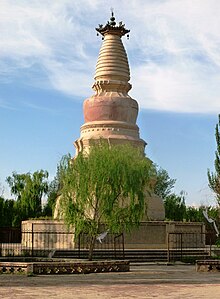

- White Horse Pagoda

- Dunhuang Limes

Museums

Transportation

Dunhuang is served by China National Highway 215 and Dunhuang Airport,

A railway branch known as the Dunhuang Railway (敦煌铁路) or the Liudun Railway (柳敦铁路), constructed in 2004-2006, connects Dunhuang with the Liugou Station on the Lanzhou-Xinjiang Railway (in Guazhou County). There is regular passenger service on the line, with overnight trains from Dunhuang to Lanzhou and Xi'an.[14]

There are plans to extend the railway from Dunhuang further south into Qinghai, connecting Dunhuang to Golmud on the Qingzang Railway. Construction work on this Golmud–Dunhuang Railway started in October 2012, and is expected to be completed in 5 years.[15]

See also

- Three hares (as a decorative motif)

- Major National Historical and Cultural Sites (Gansu)

Gallery

-

Sand dunes on the edge of Dunhuang

-

Sculpture in Dunhuang, after a mural in Mogao Caves depicting a musician playing the pipa behind his back.

-

Dunhuang airport

Footnotes

- ^ a b Cable and French (1943), p. 41.

- ^ Skrine (1926), p. 117.

- ^ Lovell (2006), pp. 74-75.

- ^ Hulsewé, A. F. P. (1979). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. Brill, Leiden. pp.75-76 ISBN 90-04-05884-2

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 133.

- ^ Bonavia (2004), p. 162.

- ^ "Silk Road, North China, C.M. Hogan, the Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham".

- ^ The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia, by Frances Wood

- ^ Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road. The British Library. 2000. ISBN 0-7123-4697-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "The International Dunhuang Project". International Dunhuang Project. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Ancient Chinese town on front lines of desertification battle, AFP, Nov 20, 2007".

- ^ "Odd patterns in Chinese desert? Spy satellite targets., MSNBC".

- ^ "Dunhuang Climate − Best time to visit". Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- ^ Dunhuang Train Schedule Template:Zh icon

- ^ 格尔木至敦煌铁路开工, Renmin Tielu Bao, 2012-10-20

References

- Baumer, Christoph. 2000. Southern Silk Road: In the Footsteps of Sir Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin. White Orchid Books. Bangkok.

- Beal, Samuel. 1884. Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, by Hiuen Tsiang. 2 vols. Trans. by Samuel Beal. London. Reprint: Delhi. Oriental Books Reprint Corporation. 1969.

- Beal, Samuel. 1911. The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang by the Shaman Hwui Li, with an Introduction containing an account of the Works of I-Tsing. Trans. by Samuel Beal. London. 1911. Reprint: Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi. 1973.

- Bonavia, Judy (2004): The Silk Road From Xi'an to Kashgar. Judy Bonavia – revised by Christoph Baumer. 2004. Odyssey Publications.

- Cable, Mildred and Francesca French (1943): The Gobi Desert. London. Landsborough Publications.

- Hill, John E. 2003. "Annotated Translation of the Chapter on the Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu." 2nd Draft Edition.[1]

- Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation. [2]

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N. 1979. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

- Legge, James. Trans. and ed. 1886. A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: being an account by the Chinese monk Fâ-hsien of his travels in India and Ceylon (AD 399-414) in search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline. Reprint: Dover Publications, New York. 1965.

- Lovell, Julia (2006). The Great Wall : China against the World. 1000 BC — AD 2000. Atlantic Books, London. ISBN 978-1-84354-215-5.

- Skrine, C. P. (1926). Chinese Central Asia. Methuen, London. Reprint: Barnes & Noble, New York. 1971. ISBN 416-60750-0.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols. Clarendon Press. Oxford. [3]

- Stein, Aurel M. 1921. Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 5 vols. London & Oxford. Clarendon Press. Reprint: Delhi. Motilal Banarsidass. 1980. [4]

- Watson, Burton (1993). Records of the Grand Historian of China. Han Dynasty II. (Revised Edition). New York, Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08167-7

- Watters, Thomas (1904–1905). On Yuan Chwang's Travels in India. London. Royal Asiatic Society. Reprint: 1973.

External links

- Crescent Lake

- Echoing-Sand Mountain

- The International Dunhuang Project - includes tens of thousands of digitised manuscripts and paintings from Dunhuang, along with historical photographs and archival material

- British Museum: A Christian figure, ink and colours on a fragment of silk from Dunhuang

- Dunhuang Collection at the British Museum

- Dunhuang Collection at the National Museum of India

- Images and travelling impressions - in Spanish