Environmental justice

| Part of a series on |

| Green politics |

|---|

|

Environmental justice is a social movement to address the unfair exposure of poor and marginalized communities to harms from hazardous waste, resource extraction, and other land uses.[1] The movement has generated hundreds of studies showing that exposure to environmental harms is inequitably distributed.[2]

The global environmental justice movement arises from place-based environmental conflicts in which local environmental defenders frequently confront multi-national corporations in resource extraction or other industries. Local outcomes of these conflicts are increasingly influenced by trans-national environmental justice networks.[3][4]

The movement began in the United States in the 1980s and was heavily influenced by the American civil rights movement. The original conception of environmental justice in the 1980s focused on harms to marginalised racial groups within rich countries such as the United States and was framed as environmental racism. The movement was later expanded to consider gender, international environmental discrimination, and inequalities within disadvantaged groups. As the movement achieved some success in more affluent countries, environmental burdens have shifted to the Global South (as for example through extractivism or the global waste trade). The movement for environmental justice has thus become more global, with some of its aims now being articulated by the United Nations.

Environmental justice scholars have produced a large interdisciplinary body of social science literature that includes political ecology, contributions to environmental law, and theories on justice and sustainability.[1][5]

Definitions

Environmental justice is typically defined as distributive justice, which is the equitable distribution of environmental risks and benefits.[6] Some definitions address procedural justice, which is the fair and meaningful participation in decision-making. Other scholars emphasise recognition justice, which is the recognition of oppression and difference in environmental justice communities. People's capacity to convert social goods into a flourishing community is a further criteria for a just society.[1][6][7]

The United States Environmental Protection Agency defines environmental justice as:[8]

the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

Environmental justice is also discussed as environmental racism or environmental inequality.[9]

History and scope

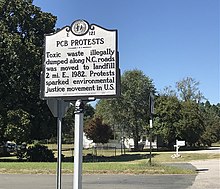

The origins of the environmental justice movement can be traced to the Indigenous environmental movement, which itself has roots in over 500 years of colonialism, oppression, and ongoing struggles for sovereignty and land rights.[10] Use of the terms 'environmental justice' and 'environmental racism' began in the United States with the 1982 PCB protests in Warren County, North Carolina.[11][12] Dumping of PCB contaminated soil in the predominately Black community of Afton sparked massive protests, and over 500 people were arrested. Subsequent studies demonstrated that race was the most important factor predicting placement of hazardous waste facilities in the US.[13] These studies were followed by widespread objections and lawsuits against hazardous waste disposal in poor, generally Black, communities.[12][14] The mainstream environmental movement began to be criticised for its predominately white affluent leadership, emphasis on conservation, and failure to address social equity concerns.[15][16]

Emergence of global movement

Through the 1970s and 1980s, grassroots movements and environmental organizations promoted regulations that increased the costs of hazardous waste disposal in the US and other industrialized countries. Exports of hazardous waste to the Global South escalated through the 1980s and 1990s.[17] Globally, disposal of toxic waste, land appropriation, and resource extraction leads to human rights violations and environmental conflict as the basis of the global environmental justice movement.[17][3][4]

International formalization of environmental justice began with the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in 1991. The summit was held in Washington, DC, and was attended by over 650 delegates from every US state, Mexico, Chile, and other countries.[18][19] Delegates adopted 17 principles of environmental justice which were circulated at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio. Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development states that individuals shall have access to information regarding environmental matters, participation in decisions, and access to justice.[20][21]

Prior to the Leadership Summit in 1991, the scope of the environmental justice movement dealt primarily with anti-toxics and harms to certain marginalized racial groups within rich countries; during the summit, it was expanded to include public health, worker safety, land use, transportation, and many other issues.[18][22] The movement was later expanded to more completely consider gender, international injustices, and inequalities within disadvantaged groups.[22] Environmental justice has become a very broad global movement, and it has contributed several concepts to political ecology that have been adopted or formalized in academic literature. These concepts include ecological debt, environmental racism, climate justice, food sovereignty, corporate accountability, ecocide, sacrifice zones, environmentalism of the poor, and others.[23]

Environmental justice seeks to expand the scope of human rights law which had previously failed to treat the relationship between the environment and human rights.[24] Most human rights treaties do not have explicitly environmental provisions. Attempts to integrate environmental protection with human rights law include the codification of the human right to a healthy environment. Integrating environmental protections into human rights law remains problematic, especially in the case of climate justice.[24]

Scholars such as Kyle Powys Whyte and Dina Gilio-Whitaker have extended the environmental justice discourse in relation to Indigenous people and settler-colonialism. Gilio-Whitaker points out that distributive justice presumes a capitalistic commodification of land that is inconsistent with Indigenous worldviews.[25] Whyte discusses environmental justice in the context of catastrophic changes brought by colonisation to the environments that Indigenous peoples have relied upon for centuries to maintain their livelihoods and identities.[26]

Environmental discrimination and conflict

The environmental justice movement seeks to address environmental discrimination and environmental racism associated with hazardous waste disposal, resource extraction, land appropriation, and other activities.[17] This environmental discrimination results in the loss of land-based traditions and economies,[22] armed violence (especially against women and indigenous people)[27] environmental degradation, and environmental conflict.[28] The global environmental justice movement arises from these local place-based conflicts in which local environmental defenders frequently confront multi-national corporations. Local outcomes of these conflicts are increasingly influenced by trans-national environmental justice networks.[3][4]

There are many divisions along which unjust distribution of environmental burdens may fall. Within the US, race is the most important determinant of environmental injustice.[29][30] In some other countries, poverty or caste (India) are important indicators.[11] Tribal affiliation is also important in some countries.[11] Environmental justice scholars Laura Pulido and David Pellow argue that recognizing environmental racism as an element stemming from the entrenched legacies of racial capitalism is crucial to the movement, with white supremacy continuing to shape human relationships with nature and labor.[31][32][33]

Environmental racism

The relationship between environmental racism and environmental inequality is recognized throughout the developed and developing world. An example of global environmental racism is the disproportionate location of hazardous waste facilities in vulnerable communities. For example, much hazardous waste in Africa is not actually produced there but rather exported by developed countries such as the U.S.[34]

Hazardous waste

As environmental justice groups have grown more successful in developed countries such as the United States, the burdens of global production have been shifted to the Global South where less-strict regulations makes waste disposal cheaper. Export of toxic waste from the US escalated throughout the 1980s and 1990s.[35][17] Many impacted countries do not have adequate disposal systems for this waste, and impacted communities are not informed about the hazards they are being exposed to.[36][37]

The Khian Sea waste disposal incident was a notable example of environmental justice issues arising from international movement of toxic waste. Contractors disposing of ash from waste incinerators in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania illegally dumped the waste on a beach in Haiti after several other countries refused to accept it. After more than ten years of debate, the waste was eventually returned to Pennsylvania.[36] The incident contributed to the creation of the Basel Convention that regulates international movement of toxic waste.[38]

Land appropriation

Countries in the Global South disproportionately bear the environmental burden of global production and the costs of over-consumption in Western societies. This burden is exacerbated by changes in land use that shift vast tracts of land away from family and subsistence farming toward multi-national investments in land speculation, agriculture, mining, or conservation.[22] Land grabs in the Global South are engendered by neoliberal ideology and differences in legal frameworks, land prices, and regulatory practices that make countries in the Global South attractive to foreign investments.[22] These land grabs endanger indigenous livelihoods and continuity of social, cultural, and spiritual practices. Resistance to land appropriation through transformative social action is also made difficult by pre-existing social inequity and deprivation; impacted communities are often already struggling just to meet their basic needs.

Resource extraction

Hundreds of studies have shown that marginalized communities are disproportionately burdened by the negative environmental consequences of resource extraction.[2] Communities near valuable natural resources are frequently saddled with a resource curse wherein they bear the environmental costs of extraction and a brief economic boom that leads to economic instability and ultimately poverty.[2] Power disparities between extraction industries and impacted communities lead to acute procedural injustice in which local communities are unable to meaningfully participate in decisions that will shape their lives.

Studies have also shown that extraction of critical minerals, timber, and petroleum may be associated with armed violence in communities that host mining operations.[27] The government of Canada found that resource extraction leads to missing and murdered indigenous women in communities impacted by mines and infrastructure projects such as pipelines.[39]

Relationships to other movements and philosophies

Climate justice

Climate change and climate justice have also been a component when discussing environmental justice and the greater impact it has on environmental justice communities.[41] Air pollution and water pollution are two contributors of climate change that can have detrimental effects such as extreme temperatures, increase in precipitation, and a rise in sea level.[41][42] Because of this, communities are more vulnerable to events including floods and droughts potentially resulting in food scarcity and an increased exposure to infectious, food-related, and water-related diseases.[41][42][43] It has been projected that climate change will have the greatest impact on vulnerable populations.[43]

Climate justice has been influenced by environmental justice, especially grassroots climate justice.[44]

Environmentalism

Relative to general environmentalism, environmental justice is seen as having a greater focus on the lives of everyday people and being more grassroots.[45] Environmental justice advocates have argued that mainstream environmentalist movements have sometimes been racist and elitist.[45][46]

Reproductive justice

Many participants in the Reproductive Justice Movement see their struggle as linked with those for environmental justice, and vice versa. Loretta Ross describes the reproductive justice framework as addressing "the ability of any woman to determine her own reproductive destiny" and argues this is "linked directly to the conditions in her community – and these conditions are not just a matter of individual choice and access."[47] Such conditions include those central to environmental justice – including the siting of toxic waste and pollution of food, air, and waterways.

Mohawk midwife Katsi Cook founded the Mother's Milk Project in the 1980s to address the toxic contamination of maternal bodies through exposure to fish and water contaminated by a General Motors Superfund site. In underscoring how contamination disproportionately impacted Akwesasne women and their children through gestation and breastfeeding, this project illustrates the intersections between reproductive and environmental justice.[48] Cook explains that, "at the breasts of women flows the relationship of those generations both to society and to the natural world."[49]

Cost barriers

One of the prominent barriers to minority participation in environmental justice is the initial costs of trying to change the system and prevent companies from dumping their toxic waste and other pollutants in areas with high numbers of minorities living in them. There are massive legal fees involved in fighting for environmental justice and trying to shed environmental racism.[50] For example, in the United Kingdom, there is a rule that the claimant may have to cover the fees of their opponents, which further exacerbates any cost issues, especially with lower-income minority groups; also, the only way for environmental justice groups to hold companies accountable for their pollution and breaking any licensing issues over waste disposal would be to sue the government for not enforcing rules. This would lead to the forbidding legal fees that most could not afford.[51] This can be seen by the fact that out of 210 judicial review cases between 2005 and 2009, 56% did not proceed due to costs.[52]

Income inequality

The relationship between economic inequality and environmental inequality plays a large role in understanding certain reasons that account for the cause of environmental inequality. The association between income inequality and environmental inequality can be measured by the environmental Kuznets curve. This curve states that when income per capita is high, the rate of pollution in that area rises until income reaches a certain threshold, once this threshold of wealth is passed then pollution in that area begins to decrease.[53] In the case of developing nations, an increase in pollution and production of greenhouse gases occurs as that nation undergoes economic growth, therefore for developing nations to escape poverty through growth pollution must be produced. This pollution is often caused through industry and manufacturing. Once the developing nation becomes a developed nation then we begin to see a drop off in pollution as a better alternative to high pollution industry can be found to stimulate the economy. Renewable energy has been more expensive to produce and maintain than traditional energy produced by fossil fuels and has only recently become as cost efficient as fossil fuels.[54] Since the discovery of greener energy sources only richer developed nations have been able to invest and integrate renewable energy into their power production industries.

In countries such as Russia, it has been found that in areas where income was higher that there was an increase in uncontrolled air pollution. However while income may have been higher in these regions a greater disparity in income inequality was found. It was discovered that "greater income inequality within a region is associated with more pollution, implying that it is not only the level of income that matters but also its distribution".[53] In Russia areas lacking in hospital beds suffer from greater air pollution than areas with higher numbers of beds per capita which implies that the poor or inadequate distribution of public services also may add to the environmental inequality of that region.[53]

Another consequence of income inequality's association with environmental inequality is the environmental privilege of consumers in developed countries, "consumers of goods and services that are produced by polluting industries [who] often are spatially and socially separated from the people who bear the impacts of the pollution".[53] Those who are working in the production of consumer goods suffer a disproportionate amount of the consequences of environmental deterioration.

Exposure health impacts

Environmental justice communities are disproportionately exposed to higher chemical pollution, reduced air quality, contaminated water sources, and overall reduced health.[55] A lack of acknowledgement and policy changes surrounding the exposures that impact the overall health of these communities leads to a decrease in both environmental and human health.[56] Environmental justice communities can be identified by various methods such as:[56]

- threshold – geographic areas

- community based identification

- population weighting

While there are multiple ways to identify environmental justice communities, common environmental exposures in these environmental justice communities include air pollution and water pollution hazards.[55] Due to a majority of environmental justice communities being of a lower socioeconomic status, many of the members of the communities work in crowded jobs with hazardous exposures such as warehouses and mines.[57] The main routes of exposure are through inhalation, absorption, and ingestion. When workers leave the work environment it is likely they take the chemicals with them on their clothing, shoes, skin, and hair.[57] The traveling of these chemicals can then reach their homes and further impact their families, including children.[57] The children of these communities have been described as a uniquely exposed population due to the way they metabolize and absorb contaminants differently than adults.[57] Compared to children in other communities, children in environmental justice communities may be exposed to a higher level of contaminants throughout the life course, beginning from utero (through the placenta), infancy (through breast milk), early childhood and beyond.[57] Due to the increased exposure they are at a greater risk for adverse health effects like respiratory conditions, gastrointestinal conditions, and mental conditions.

The placement of fracking sites and concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) in some of these areas are also large contributors to the adverse health effects experienced by members of these communities.[58] The CAFOs also release harmful gas emissions into the air (ammonia, volatile organic compounds, endotoxins, etc.) greatly reducing the surrounding air quality.[58] They can also pollute the soil and nearby water sources. Fracking sites can release toxic emissions, particularly methane, that also pollutes the air and contaminates the water.[59]

On a global scale, the recent boom in fast fashion has also been a major exposure to environmental hazards in environmental justice communities due to the quick manufacturing and dumping of large quantities of products.[60] 95% of clothing production takes place in low- or middle-income countries where the workers are under-resourced.[60] The occupational hazards such as poor ventilation can lead to respiratory hazards including synthetic air particles and cotton dust.[60] The textile dyeing can also result in an exposure hazard if the water used to for the dyeing is not treated prior to entering the local water systems leading to the release of toxicants and heavy metals in the water used by residents and for livestock.[60]

Around the world

In recent years environmental justice campaigns have also emerged in other parts of the world, such as India, South Africa, Israel, Nigeria, Mexico, Hungary, Uganda, and the United Kingdom. In Europe for example, there is evidence to suggest that the Romani people and other minority groups of non-European descent are suffering from environmental inequality and discrimination.[61][62]

Africa

Kenya

Kenya has, since independence in 1963, focused on environmental protectionism. Environmental activists such as Wangari Maathai stood for and defend natural and environmental resources, often coming into conflict with the Daniel Arap Moi and his government. The country has suffered Environmental issues arising from rapid urbanization especially in Nairobi, where the public space, Uhuru Park, and game parks such as the Nairobi National Park have suffered encroachment to pave way for infrastructural developments like the Standard Gage Railway and the Nairobi Expressway. one of the Top environmental lawyers, Kariuki Muigua, has championed environmental Justice and access to information and legal protection, authoring the Environmental Justice Thesis on Kenya's milestones.[63]

Environmental Justice is guarded by and protected by the 2010 constitution, with legal procedures against damaging practices and funding from the national government and external donors to secure a clean, healthy and Eco-balanced environment. Nairobi, however, continues to experience poor environmental protection, with the Nairobi River always clogging and being emptied, an issue that the Government blames on high informal sector and business development in the city. the sector has poor waste disposals, leading to pollution.

Nigeria

From 1956 to 2006, up to 1.5 million tons of oil were spilled in the Niger Delta, (50 times the volume spilled in the Exxon Valdez disaster).[64][65] Indigenous people in the region have suffered the loss of their livelihoods as a result of these environmental issues, and they have received no benefits in return for enormous oil revenues extracted from their lands. Environmental conflicts have exacerbated ongoing conflict in the Niger Delta.[66][67][68]

Ogoni people, who are indigenous to Nigeria's oil-rich Delta region have protested the disastrous environmental and economic effects of Shell Oil's drilling and denounced human rights abuses by the Nigerian government and by Shell. Their international appeal intensified dramatically after the execution in 1995 of nine Ogoni activists, including Ken Saro-Wiwa, who was a founder of the nonviolent Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP).[69][66][67][68]

South Africa

Under colonial and apartheid governments in South Africa, thousands of black South Africans were removed from their ancestral lands to make way for game parks. Earthlife Africa was formed in 1988, making it Africa's first environmental justice organisation. In 1992, the Environmental Justice Networking Forum (EJNF), a nationwide umbrella organization designed to coordinate the activities of environmental activists and organizations interested in social and environmental justice, was created. By 1995, the network expanded to include 150 member organizations and by 2000, it included over 600 member organizations.[70]

With the election of the African National Congress (ANC) in 1994, the environmental justice movement gained an ally in government. The ANC noted "poverty and environmental degradation have been closely linked" in South Africa.[attribution needed] The ANC made it clear that environmental inequalities and injustices would be addressed as part of the party's post-apartheid reconstruction and development mandate. The new South African Constitution, finalized in 1996, includes a Bill of Rights that grants South Africans the right to an "environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being" and "to have the environment protected, for the benefit of present and future generations through reasonable legislative and other measures that

- prevent pollution and ecological degradation;

- promote conservation; and

- secure ecologically sustainable development and use of natural resources while promoting justifiable economic and social development".[70]

South Africa's mining industry is the largest single producer of solid waste, accounting for about two-thirds of the total waste stream.[vague] Tens of thousands of deaths have occurred among mine workers as a result of accidents over the last century.[71] There have been several deaths and debilitating diseases from work-related illnesses like asbestosis.[citation needed] For those who live next to a mine, the quality of air and water is poor. Noise, dust, and dangerous equipment and vehicles can be threats to the safety of those who live next to a mine as well.[citation needed] These communities are often poor and black and have little choice over the placement of a mine near their homes. The National Party introduced a new Minerals Act that began to address environmental considerations by recognizing the health and safety concerns of workers and the need for land rehabilitation during and after mining operations. In 1993, the Act was amended to require each new mine to have an Environmental Management Program Report (EMPR) prepared before breaking ground. These EMPRs were intended to force mining companies to outline all the possible environmental impacts of the particular mining operation and to make provision for environmental management.[70]

In October 1998, the Department of Minerals and Energy released a White Paper entitled A Minerals and Mining Policy for South Africa, which included a section on Environmental Management. The White Paper states "Government, in recognition of the responsibility of the State as custodian of the nation's natural resources, will ensure that the essential development of the country's mineral resources will take place within a framework of sustainable development and in accordance with national environmental policy, norms, and standards". It adds that any environmental policy "must ensure a cost-effective and competitive mining industry."[70]

Asia

Noah Diffenbaugh and Marshall Burke in their study of inequality in Asia demonstrated the interactionalism of economic inequality and global warming. For instance, globalization and industrialization increased the chances of global warming. However, industrialization also allowed wealth inequality to perpetuate. For example, New Delhi is the epicenter of the industrial revolution in the Indian continent, but there is significant wealth disparity. Furthermore, because of global warming, countries like Sweden and Norway can capitalize on warmer temperatures, while most of the world's poorest countries are significantly poorer than they would have been if global warming had not occurred.[72][73]

China

In China, factories create harmful waste such as nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide which cause health risks. Journalist and science writer Fred Pearce notes that in China "most monitoring of urban air still concentrates on one or at most two pollutants, sometimes particulates, sometimes nitrogen oxides or sulfur dioxides or ozone. Similarly, most medical studies of the impacts of these toxins look for links between single pollutants and suspected health effects such as respiratory disease and cardiovascular conditions."[74] The country emits about a third of all the human-made sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), and particulates pollution in the world.[74] The Global Burden of Disease Study, an international collaboration, estimates that 1.1 million Chinese die from the effects of this air pollution each year, roughly a third of the global death toll."[74] The economic cost of deaths due to air pollution is estimated at 267 billion yuan (US$38 billion) per year.[75]

Indonesia

Environmental conflicts in Indonesia include:

- The Arun gas field where ExxonMobil's development of a natural gas export industry contributed to the insurgency in Aceh in which secessionist fighters led by the Free Aceh Movement attempted to gain independence from the central government which had taken billions in gas revenues from the region without much benefit to the Aceh province. Violence directed toward the gas industry led Exxon to contract with the Indonesian military for protection of the Arun field and subsequent human rights abuses in Aceh.[76]

South Korea

South Korea has a relatively short history of environmental justice compared to other countries in the west. As a result of rapid industrialization, people started to have awareness on pollution, and from the environmental discourses the idea of environmental justice appeared. The concept of environmental justice appeared in South Korea in late 1980s.[77]

South Korea experienced rapid economic growth (which is commonly referred to as the 'Miracle on the Han River') in the 20th century as a result of industrialization policies adapted by Park Chung-hee after 1970s. The policies and social environment had no room for environmental discussions, which aggravated the pollution in the country.[78]

Environmental movements in South Korea started from air pollution campaigns. As the notion of environment pollution spread, the focus on environmental activism shifted from existing pollution to preventing future pollution, and the organizations eventually started to criticize the government policies that are neglecting the environmental issues.[79] The concept of environmental justice was introduced in South Korea among the discussions of environment after 1990s. While the environmental organizations analyzed the condition of pollution in South Korea, they noticed that the environmental problems were inequitably focused especially on regions where people with low social and economic status were concentrated.

The problems of environmental injustice have arisen by environment related organizations, but approaches to solve the problems were greatly supported by the government, which developed various policies and launched institution. These actions helped raise awareness of environmental justice in South Korea. Existing environment policies were modified to cover environmental justice issues.

Environmental justice began to be widely recognized in the 1990s through policy making and researches of related institutions. For example, the Ministry of Environment, which was founded in 1992, launched Citizen's Movement for Environmental Justice (CMEJ) to raise awareness of the problem and figure out appropriate plans.[80] As a part of its activities, Citizen's Movement for Environmental Justice (CMEJ) held Environmental Justice forum in 1999, to gather and analyze the existing studies on the issue which were done sporadically by various organizations. CMEJ started as a small organization, but it is expanding. In 2002, CMEJ had more than five times the numbers of members and three times the budget it had in the beginning year.[77][81]

Environmental injustice is still an ongoing problem. One example is the construction of Saemangeum Seawall. The construction of Saemangeum Seawall, which is the world's longest dyke (33 kilometers) runs between Yellow Sea and Saemangeum estuary, was part of a government project initiated in 1991.[82] The project raised concerns on the destruction of ecosystem and taking away the local residential regions. It caught the attention of environmental justice activists because the main victims were low-income fishing population and their future generations. This is considered as an example of environmental injustice which was caused by the execution of exclusive development-centered policy.

The construction of Seoul-Incheon canal also raised environmental justice controversies.[83] The construction took away the residential regions and farming areas of the local residents. Also, the environment worsened in the area because of the appearance of wet fogs which was caused by water deprivation and local climate changes caused by the construction of canal. The local residents, mostly people with weak economic basis, were severely affected by the construction and became the main victims of such environmental damages. While the socially and economically weak citizens suffered from the environmental changes, most of the benefits went to the industries and conglomerates with political power.

Construction of industrial complex was also criticized in the context of environmental justice. The conflict in Wicheon region is one example. The region became the center of controversy when the government decided to build industrial complex of dye houses, which were formerly located in Daegu metropolitan region. As a result of the construction, Nakdong River, which is one of the main rivers in South Korea, was contaminated and local residents suffered from environmental changes caused by the construction.[84][85]

Environmental justice is a growing issue in South Korea. Although the issue is not yet widely recognized compared to other countries, many organizations beginning to recognize the issue.[86]

Australia

In Australia, the "Environmental Justice Movement" is not defined as it is in the United States. Australia does have some discrimination mainly in the siting of hazardous waste facilities in areas where the people are not given proper information about the company. The injustice that takes place in Australia is defined as environmental politics on who get the unwanted waste site or who has control over where factory opens up. The movement towards equal environmental politics focuses more on who can fight for companies to build, and takes place in the parliament; whereas, in the United States Environmental Justice is trying to make nature safer for all people.[87]

Europe

For further information, see Environmental racism in Europe

In Europe, the Romani peoples are ethnic minorities and differ from the rest of the European people by their culture, language, and history. The environmental discrimination that they experience ranges from the unequal distribution of environmental harms as well as the unequal distribution of education, health services and employment. In many countries Romani peoples are forced to live in the slums because many of the laws to get residence permits are discriminatory against them. This forces Romani people to live in urban "ghetto" type housing or in shantytowns. In the Czech Republic and Romania, the Romani peoples are forced to live in places that have less access to running water and sewage, and in Ostrava, Czech Republic, the Romani people live in apartments located above an abandoned mine, which emits methane. Also in Bulgaria, the public infrastructure extends throughout the town of Sofia until it reaches the Romani village where there is very little water access or sewage capacity.[88]

The European Union is trying to strive towards environmental justice by putting into effect declarations that state that all people have a right to a healthy environment. The Stockholm Declaration, the 1987 Brundtland Commission's Report – "Our Common Future", the Rio Declaration, and Article 37 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, all are ways that the Europeans have put acts in place to work toward environmental justice.[88] Europe also funds action-oriented projects that work on furthering Environmental Justice throughout the world. For example, EJOLT (Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and Trade) is a large multinational project supported through the FP7 Science in Society budget line from the European Commission.[further explanation needed] From March 2011 to March 2015, 23 civil society organizations and universities from 20 countries in Europe, Africa, Latin-America, and Asia are, and have promised to work together on advancing the cause of Environmental Justice. EJOLT is building up case studies, linking organisations worldwide, and making an interactive global map of Environmental Justice.[89] A recent study of Environmental justice in Natura 2000 notes that an environmental just policy can empower residents with the capacity to initiate social change. In return, this social change modifies the form that empowerment will take.

Similar to other countries around the world, the European Environment Agency (EEA) identifies that environmental inequality issues remain at the core of environment, society, and economy. Social circumstances often seem to correlate with the exposure, vulnerability, and sensitivity to environmental hazards. In Europe, "the quality of the environment varies significantly across Europe; in general terms between east and west, but also between countries, regions and neighbourhoods within cities" (Ganzleben and Kazmierczak, par.10). The EEA ran a report that was able to identify the inequality between exposure to environmental hazards such as pollution, noise, and high temperatures, and socioeconomic status. The results of the report established that poverty-stricken European residential areas are more inclined to be exposed to these environmental health hazards which tend to contribute to more environmental stressors. However, the nature of this evidence varies due to geographical circumstances. For example, Western Europe has more extensive examples of environmental health hazards due to their governments' in-comprehensive knowledge of these various health hazards and how they affect their residential areas.[90]

Sweden

Sweden became the first country to ban DDT in 1969.[91] In the 1980s, women activists organized around preparing jam made from pesticide-tainted berries, which they offered to the members of parliament.[92][93] Parliament members refused, and this has often been cited as an example of direct action within ecofeminism.

United Kingdom

Whilst the predominant agenda of the Environmental Justice movement in the United States has been tackling issues of race, inequality, and the environment, environmental justice campaigns around the world have developed and shifted in focus. For example, the EJ movement in the United Kingdom is quite different. It focuses on issues of poverty and the environment, but also tackles issues of health inequalities and social exclusion.[94] A UK-based NGO, named the Environmental Justice Foundation, has sought to make a direct link between the need for environmental security and the defense of basic human rights.[95] They have launched several high-profile campaigns that link environmental problems and social injustices. A campaign against illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing highlighted how 'pirate' fisherman are stealing food from local, artisanal fishing communities.[96][97] They have also launched a campaign exposing the environmental and human rights abuses involved in cotton production in Uzbekistan. Cotton produced in Uzbekistan is often harvested by children for little or no pay. In addition, the mismanagement of water resources for crop irrigation has led to the near eradication of the Aral Sea.[98] The Environmental Justice Foundation has successfully petitioned large retailers such as Wal-mart and Tesco to stop selling Uzbek cotton.[99]

Building of alternatives to climate change

In France, numerous Alternatiba events, or villages of alternatives, are providing hundreds of alternatives to climate change and lack of environmental justice, both in order to raise people's awareness and to stimulate behaviour change. They have been or will be organized in over sixty different French and European cities, such as Bilbao, Brussels, Geneva, Lyon or Paris.

North America

United States

Definitions of environmental inequality typically emphasize either 'disparate exposure' (unequal exposure to environmental harm) or 'discriminatory intent' (often based on race). Disparate exposure has health and social impacts.[100] Poverty and race are associated with environmental injustice. Poor people account for more than 20% of the human health impacts from industrial toxic air releases, compared to 12.9% of the population nationwide.[101] Some studies that test statistically for effects of race and ethnicity, while controlling for income and other factors, suggest racial gaps in exposure that persist across all bands of income.[102]

States may also see placing toxic facilities near poor neighborhoods as preferential from a Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) perspective. A CBA may favor placing a toxic facility near a city of 20,000 poor people than near a city of 5,000 wealthy people.[103] Terry Bossert of Range Resources reportedly has said that it deliberately locates its operations in poor neighbourhoods instead of wealthy areas where residents have more money to challenge its practices.[104] Northern California's East Bay Refinery Corridor is an example of the disparities associated with race and income and proximity to toxic facilities.[105]

Women

The impacts of climate change have disproportionate effects on women and girls.[106] Women tend to experience higher risks and greater burdens of climate change, because climate change is not gender neutral. Extreme weather events are tied to early marriage, sex trafficking, domestic violence, displacement, income loss, food insecurity, water scarcity, and health complications.[107][106] In 2020, the Eta and Iota Hurricanes caused damage to Central American states.[107] Many were displaced but it was women who were hit hardest. Similarly, in India, droughts have left women the most vulnerable compared to men.[108]

It has been argued that environmental justice issues generally tend to affect women in communities more so than they affect men. Women also tend to be the leaders in environmental justice activist movements. As such, it is growing to be a mainstream feminist issue.[109] Under feminist approaches to environmental justice, environmental issues and climate change are viewed through a lens that asserts that the patriarchy, white supremacy, racism, and capitalism are contributors to the impact that climate change has on women.[107] This type of analysis to environmental justice advocates strategies that address the root causes of inequality, transform power relations, and support women's rights.[110]

African-Americans

African-Americans are affected by a variety of Environmental Justice issues. One notorious example is the "Cancer Alley" region of Louisiana.[111] This 85-mile stretch of the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans is home to 125 companies that produce one quarter of the petrochemical products manufactured in the United States. The United States Commission on Civil Rights has concluded that the African-American community has been disproportionately affected by Cancer Alley as a result of Louisiana's current state and local permit system for hazardous facilities, as well as their low socio-economic status and limited political influence.[112] Another incidence of long-term environmental injustice occurred in the "West Grove" community of Miami, Florida. From 1925 to 1970, the predominately poor, African American residents of the "West Grove" endured the negative effects of exposure to carcinogenic emissions and toxic waste discharge from a large trash incinerator called Old Smokey.[113] Despite official acknowledgement as a public nuisance, the incinerator project was expanded in 1961. It was not until the surrounding, predominantly white neighborhoods began to experience the negative impacts from Old Smokey that the legal battle began to close the incinerator.

Indigenous Groups

Indigenous groups are often the victims of environmental injustices. Native Americans have suffered abuses related to uranium mining in the American West. Churchrock, New Mexico, in Navajo territory was home to the longest continuous uranium mining in any Navajo land. From 1954 until 1968, the tribe leased land to mining companies who did not obtain consent from Navajo families or report any consequences of their activities. Not only did the miners significantly deplete the limited water supply, but they also contaminated what was left of the Navajo water supply with uranium. Kerr-McGee and United Nuclear Corporation, the two largest mining companies, argued that the Federal Water Pollution Control Act did not apply to them, and maintained that Native American land is not subject to environmental protections. The courts did not force them to comply with US clean water regulations until 1980.[112]

Latinos

The most common example of environmental injustice among Latinos is the exposure to pesticides faced by farmworkers. After DDT and other chlorinated hydrocarbon pesticides were banned in the United States in 1972, farmers began using more acutely toxic organophosphate pesticides such as parathion. A large portion of farmworkers in the US are working as undocumented immigrants, and as a result of their political disadvantage, are not able to protest against regular exposure to pesticides or benefit from the protections of Federal laws.[112] Exposure to chemical pesticides in the cotton industry also affects farmers in India and Uzbekistan. Banned throughout much of the rest of the world because of the potential threat to human health and the natural environment, Endosulfan is a highly toxic chemical, the safe use of which cannot be guaranteed in the many developing countries it is used in. Endosulfan, like DDT, is an organochlorine and persists in the environment long after it has killed the target pests, leaving a deadly legacy for people and wildlife.[114]

Residents of cities along the US-Mexico border are also affected. Maquiladoras are assembly plants operated by American, Japanese, and other foreign countries, located along the US-Mexico border. The maquiladoras use cheap Mexican labor to assemble imported components and raw material, and then transport finished products back to the United States. Much of the waste ends up being illegally dumped in sewers, ditches, or in the desert. Along the Lower Rio Grande Valley, maquiladoras dump their toxic wastes into the river from which 95 percent of residents obtain their drinking water. In the border cities of Brownsville, Texas, and Matamoros, Mexico, the rate of anencephaly (babies born without brains) is four times the national average.[115]

South America

Ecuador

Notable environmental justice movements in Ecuador have arisen from several local conflicts:

- Chevron Texaco's oil operations in the Lago Agro oil field resulted in spillage of seventeen million gallons of crude oil into local water supplies between 1967 and 1989. They also dumped over 19 billion gallons of toxic wastewater into unlined open pits and regional rivers.[116] Represented by US lawyer Steven Donziger, Indigenous people fought Chevron in US and Ecuadorian courts for decades in attempts to recover damages.[117]

Transnational movement networks

Many of the Environmental Justice Networks that began in the United States expanded their horizons to include many other countries and became Transnational Networks for Environmental Justice. These networks work to bring Environmental Justice to all parts of the world and protect all citizens of the world to reduce the environmental injustice happening all over the world. Listed below are some of the major Transnational Social Movement Organizations.[36]

- Basel Action Network – works to end toxic waste dumping in poor undeveloped countries from the rich developed countries.[118]

- GAIA (Global Anti-Incinerator Alliance) – works to find different ways to dispose of waste other than incineration. This company has people working in over 77 countries throughout the world.

- GR (Global Response) – works to educate activists and the upper working class how to protect human rights and the ecosystem.

- Greenpeace International – which was the first organization to become the global name of Environmental Justice. Greenpeace works to raise the global consciousness of transnational trade of toxic waste.

- Health Care without Harm – works to improve public health by reducing the environmental impacts of the health care industry.[119]

- International Campaign for Responsible Technology – works to promote corporate and government accountability with electronics and how the disposal of technology affect the environment.

- International POPs Elimination Network – works to reduce and eventually end the use of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) which are harmful to the environment.

- PAN (Pesticide Action Network) – works to replace the use of hazardous pesticides with alternatives that are safe for the environment.[120]

Outer space

Over recent years social scientists have begun to view outer space in an environmental conceptual framework.[121] Klinger, an environmental geographer, analyses the environmental features of outer space from the perspective of several schools of geopolitical.[122] From a classical geopolitical approach, for instance, people's exploration of the outer space domain is, in fact, a manifestation of competing and conflicting interests between states, i.e., outer space is an asset used to strengthen and consolidate geopolitical power and has strategic value.[123] From the perspective of environmental geopolitics, the issue of sustainable development has become a consensus politics.[124] Countries thus cede power to international agreements and supranational organizations to manage global environmental issues.[125] Such co-produced practices are followed in the human use of outer space, which means that only powerful nations are capable of reacting to protect the interests of underprivileged countries, so far from there being perfect environmental justice in environmental geopolitics.[126]

Human interaction with outer space is environmentally based since a measurable environmental footprint will be left when modifying the Earth's environment (e.g., local environmental changes from launch sites) to access outer space, developing space-based technologies to study the Earth's environment, exploring space with spacecraft in orbit or by landing on the Moon, etc.[122] Different stakeholders have competing territorial agendas for this vast space; thus, the ownership of these footprints is governed by geopolitical power and relations, which means that human involvement with outer space falls into the field of environmental justice.[122]

Activities on Earth

On Earth, the environmental geopolitics of outer space is directly linked to issues of environmental justice - the launch of spacecraft and the impact of their launch processes on the surrounding environment, and the impact of space-based related technologies and facilities on the development process of human society.[122] As both processes require the support of industry, infrastructure, and networks of information and take place in specific locations, this leads to continuous interaction with local territorial governance.[127]

Launches and infrastructures

Rockets are generally launched in areas where conventional and potentially catastrophic blast damage can be controlled, generally in an open and unoccupied territory.[128] Despite the absence of human life and habitation, other forms of life exist in these open territories, maintaining the local ecological balance and material cycles.[128] Toxic particulate matter from rocket launches can cause localized acid rain, plant and animal mortality, reduced food production, and other hazards.[129]

Moreover, space activities result in environmental injustice on a global scale. Spacecraft are the only contributors to direct human-derived pollution in the stratosphere, which comes mostly from the launch activities of rich economies in the northern hemisphere, while the global north bears more of the environmental consequences.[130][131]

Environmental injustice is further evidenced by the limited research into the effects on downstream human and non-human communities and the inadequate tracking of pollutants in ecological chains and environments.[132]

Space-based technologies

While space-based technologies have been applied to tracking natural disasters and the spread of pollutants,[133] access to these technologies and the monitoring of data is deeply uneven within and between countries, exacerbating environmental injustice. Further, the use of technology by powerful countries can even lead to the creation of policies and institutions in less privileged nations, changing land-use regimes to favor or disadvantage the survival of certain human groups. For example, in the decades following the publication of the first report on the use of satellite imagery to measure rainforest deforestation in the 1980s, several environmental groups rose to prominence and also influenced changes in domestic policy in Brazil.[134]

See also

- Alton, Rhode Island - a town struggling with a large, polluting dye company

- Carbon fee and dividend

- Climate resilience

- Degrowth

- Ecocide

- Ecological civilization

- Environmental contract

- Environmental crime

- Environmental dumping

- Environmental history

- Environmental Justice Foundation

- Environmental justice and coal mining in Appalachia

- Environmental Racism in the United States

- Environmental sociology

- Equality impact assessment

- Extinction debt

- Fenceline community

- Global waste trade

- Green New Deal

- Greening

- Health equity

- Human impact on the environment

- Hunters Point, San Francisco, California - a neighborhood next to a Superfund site

- List of environmental lawsuits

- Pollution is Colonialism

- Netherlands fallacy

- Resource justice

- Rights of nature

- Rural Action - an organization promoting social and environmental justice in Appalachian Ohio

- Sustainable development

- Toxic 100

- Toxic colonialism

- Solarpunk

References

- ^ a b c Schlosberg, David. (2007) Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b c Malin, Stephanie (June 25, 2019). "Environmental justice and natural resource extraction: intersections of power, equity and access". Environmental Sociology. 5 (2): 109–116. doi:10.1080/23251042.2019.1608420. S2CID 198588483 – via Taylor and Francis.

- ^ a b c Scheidel, Arnim (July 2020). "Environmental conflicts and defenders: A global overview". Global Environmental Change. 63: 102104. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102104. PMC 7418451. PMID 32801483.

- ^ a b c Martinez Alier, Joan; Temper, Leah; Del Bene, Daniela; Scheidel, Arnim (2016). "Is there a global environmental justice movement?". Journal of Peasant Studies. 43 (3): 731–755. doi:10.1080/03066150.2016.1141198. S2CID 156535916.

- ^ Miller, G. Tyler Jr. (2003). Environmental Science: Working With the Earth (9th ed.). Pacific Grove, California: Brooks/Cole. p. G5. ISBN 0-534-42039-7.

- ^ a b Schlosberg, David (2002). Light, Andrew; De-Shalit, Avner (eds.). Moral and Political Reasoning in Environmental Practice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. p. 79. ISBN 0262621649.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Zwarteveen, Margreet Z.; Boelens, Rutgerd (February 23, 2014). "Defining, researching and struggling for water justice: some conceptual building blocks for research and action". Water International. 39 (2): 147. doi:10.1080/02508060.2014.891168. ISSN 0250-8060. S2CID 154913910.

- ^ "Environmental Justice". U.S. EPA. November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 9, 2020.

- ^ Environmental Inequality by Julie Gobert https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org/en/society/environmental-inequalities/

- ^ Clark, Brett (2002). "The Indigenous Environmental Movement in the United States". Organization & Environment. 15 (4): 410–442. doi:10.1177/1086026602238170. S2CID 145206960.

- ^ a b c Martinez-Alier, Joan (2014). "Between activism and science: grassroots concepts for sustainability coined by Environmental Justice Organizations" (PDF). Journal of Political Ecology. 21: 19–60. doi:10.2458/v21i1.21124.

- ^ a b Perez, Alejandro Colsa (2015). "Evolution of the environmental justice movement: activism, formalization and differentiation". Environmental Research Letters. 10 (10): 105002. Bibcode:2015ERL....10j5002C. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/10/10/105002. S2CID 154368751.

- ^ Chavis, Benjamin F.; Goldman, Benjamin A.; Lee, Charles (1987). Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States: A National Report on the Racial and Socio-economic Characteristics of Communities with Hazardous Waste Sites (Report). Commission for Racial Justice, United Church of Christ.

- ^ Cole, Luke and Sheila R. Foster. (2001) From the Ground Up: Environmental Racism and the Rise of the Environmental Justice Movement. New York University Press.

- ^ Britton-Purdy, Jedediah (December 7, 2016). "Environmentalism Was Once a Social-Justice Movement". The Atlantic.

- ^ Morrison, Denton (September 1986). "Environmentalism and elitism: a conceptual and empirical analysis". Environmental Management. 10 (5). New York: 581–589. Bibcode:1986EnMan..10..581M. doi:10.1007/BF01866762. S2CID 153561660.

- ^ a b c d Adeola, Francis (2001). "Environmental Injustice and Human Rights Abuse: The States, MNCs, and Repression of Minority Groups in the World System". Human Ecology Review. 8 (1): 39–59. JSTOR 24707236 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Bullard, Robert D (2001). "Environmental Justice in the 21st Century: Race Still Matters". Phylon. 49 (3–4): 151–171. doi:10.2307/3132626. JSTOR 3132626.

- ^ Bullard, Robert (2003). "Environmental justice for all" (PDF). Crisis. 110: 24.

- ^ "UNEP - Principle 10 and the Bali Guideline". April 26, 2018.

- ^ We, the People of Color (1991). "Principles of Environmental Justice" (PDF). EJ Net.

- ^ a b c d e Busscher, Nienke; Parra, Constanza; Vanclay, Frank (2020). "Environmental justice implications of land grabbing for industrial agriculture and forestry in Argentina". Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 63 (3): 500–522. doi:10.1080/09640568.2019.1595546. S2CID 159153413 – via Taylor and Francis Online.

- ^ Martinez-Alier, Joan; Anguelovski, Isabelle; Bond, Patrick; Del Bene, Daniela; Demaria, Federico; Gerber, Julien-Francois (2014). "Between activism and science: grassroots concepts for sustainability coined by Environmental Justice Organizations" (PDF). Journal of Political Ecology. 21: 19–60. doi:10.2458/v21i1.21124.

- ^ a b Boyle, Alan (October 11, 2012). "Human Rights and the Environment: Where Next?". European Journal of International Law. 23:3 (3): 613–642. doi:10.1093/ejil/chs054 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ Gilio-Whitaker, Dina (March 6, 2017). "What Environmental Justice Means in Indian Country". KCET. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ "Our ancestors' dystopia now: indigenous conservation and the Anthropocene" (PDF), The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, pp. 222–231, January 6, 2017, retrieved December 9, 2021

- ^ a b Downey, Liam (November 20, 2010). "Natural Resource Extraction, Armed Violence, and Environmental Degradation". Organization and Environment. 23 (4): 417–445. doi:10.1177/1086026610385903. PMC 3169238. PMID 21909231.

- ^ Lerner, Steve (2005). Diamond: A Struggle for Environmental Justice in Louisiana's Chemical Corridor. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- ^ Colquette, Kelly Michelle; Robertson, Elizabeth A Henry (1991). "Environmental Racism: The Causes, Consequences, and Commendations". Tulane Environmental Law Journal. 5 (1): 153–207. JSTOR 43291103 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Skelton, Renee; Miller, Vernice (March 17, 2016). "The Environmental Justice Movement". National Resource Defense Council. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ^ Pulido, Laura; De Lara, Juan (March 2018). "Reimagining 'justice' in environmental justice: Radical ecologies, decolonial thought, and the Black Radical Tradition". Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space. 1 (1–2): 76–98. doi:10.1177/2514848618770363. ISSN 2514-8486. S2CID 149765978.

- ^ Pellow, David; Vazin, Jasmine (July 19, 2019). "The Intersection of Race, Immigration Status, and Environmental Justice". Sustainability. 11 (14): 3942. doi:10.3390/su11143942.

- ^ Pulido, Laura (August 1, 2017). "Geographies of race and ethnicity II: Environmental racism, racial capitalism and state-sanctioned violence". Progress in Human Geography. 41 (4): 524–533. doi:10.1177/0309132516646495. ISSN 0309-1325. S2CID 147792869.

- ^ "The transboundary shipments of hazardous wastes", International Trade in Hazardous Wastes, Routledge, April 23, 1998, doi:10.4324/9780203476901.ch4, ISBN 9780419218906

- ^ Clapp, Jennifer. "Distance of Waste: Overconsumption in a Global Economy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 5, 2011.

- ^ a b c Pellow, David Naguib. 2007. Resisting Global Toxics. The MIT Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- ^ Park, Rozelia S. (1997–1998). "An Examination of International Environmental Racism through the Lens of Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Waste". Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies. Indiana, IL.

- ^ Cunningham, William P & Mary A (2004). Principles of Environmental Science. McGrw-Hill Further Education. p. Chapter 13, Further Case Studies. ISBN 0072919833.

- ^ Reclaiming Power and Place: The Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (PDF) (Report). Vol. 1a. p. 728. ISBN 978-0-660-29274-8. CP32-163/2-1-2019E-PDF

- ^ "Emissions Gap Report 2020 / Executive Summary" (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. 2021. p. XV Fig. ES.8. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2021.

- ^ a b c Reckien, Diana; Lwasa, Shuaib; Satterthwaite, David; McEvoy, Darryn; Creutzig, Felix; Montgomery, Mark; Schensul, Daniel; Balk, Deborah; Khan, Iqbal Alam (2018), "Equity, Environmental Justice, and Urban Climate Change", Climate Change and Cities, Cambridge University Press, pp. 173–224, doi:10.1017/9781316563878.013, ISBN 9781316563878, retrieved December 5, 2021

- ^ a b Haines, Andy (January 7, 2004). "Health Effects of Climate Change". JAMA. 291 (1): 99–103. doi:10.1001/jama.291.1.99. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 14709582.

- ^ a b Moellendorf, Darrel (March 2015). "Climate Change Justice". Philosophy Compass. 10 (3): 173–186. doi:10.1111/phc3.12201. ISSN 1747-9991.

- ^ Schlosberg, David; Collins, Lisette B. (May 2014). "From environmental to climate justice: climate change and the discourse of environmental justice". WIREs Climate Change. 5 (3): 359–374. doi:10.1002/wcc.275. ISSN 1757-7780. S2CID 145546565.

- ^ a b "Introduction Revisiting the Environmental Justice Challenge to Environmentalism", Environmental Justice and Environmentalism, The MIT Press, 2007, doi:10.7551/mitpress/2781.003.0003, ISBN 9780262282918, retrieved June 25, 2022

- ^ "Environmentalism vs. Environmental Justice | Sustainability | UMN Duluth". sustainability.d.umn.edu. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ Ross, Loretta (2007). Reproductive Justice Briefing Book; A Primer on Reproductive Justice and Social Change. Berkeley, California: Berkeley Law. pp. 4–5.

- ^ Hoover, Elizabeth (2017). The River is In Us: Fighting Toxics in a Mohawk Community. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9781517903039.

- ^ Sillman, Jael (2016). Undivided Rights, Women of Color Organize for Reproductive Justice. Chicago, Illinois: Haymarket Books. p. 126. ISBN 9781608466177.

- ^ Kennedy, Amanda; Schafft, Kai A.; Howard, Tanya M. (August 3, 2017). "Taking away David's sling: environmental justice and land-use conflict in extractive resource development". Local Environment. 22 (8): 952–968. doi:10.1080/13549839.2017.1309369. ISSN 1354-9839. S2CID 157888833.

- ^ Jeffries, Elisabeth. "What price environmental justice?". Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ "Cost Barriers to Environmental Justice". Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Vornovytskyy, Marina S.; Boyce, James K. (January 1, 2010). Economic Inequality and Environmental Quality: Evidence of Pollution Shifting in Russia. ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. OCLC 698200672.

- ^ Sharma, Gaurav. "Production Cost Of Renewable Energy Now 'Lower' Than Fossil Fuels". Forbes. Retrieved April 7, 2019.

- ^ a b Collins, Mary B; Munoz, Ian; JaJa, Joseph (January 1, 2016). "Linking 'toxic outliers' to environmental justice communities". Environmental Research Letters. 11 (1): 015004. Bibcode:2016ERL....11a5004C. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/11/1/015004. ISSN 1748-9326. S2CID 11839990.

- ^ a b Rowangould, Dana; Karner, Alex; London, Jonathan (June 2016). "Identifying environmental justice communities for transportation analysis". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 88: 151–162. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2016.04.002. ISSN 0965-8564.

- ^ a b c d e Gochfeld, Michael; Burger, Joanna (December 2011). "Disproportionate Exposures in Environmental Justice and Other Populations: The Importance of Outliers". American Journal of Public Health. 101 (S1): S53–S63. doi:10.2105/ajph.2011.300121. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3222496. PMID 21551384.

- ^ a b Son, Ji-Young; Muenich, Rebecca L.; Schaffer-Smith, Danica; Miranda, Marie Lynn; Bell, Michelle L. (April 2021). "Distribution of environmental justice metrics for exposure to CAFOs in North Carolina, USA". Environmental Research. 195: 110862. Bibcode:2021ER....195k0862S. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.110862. ISSN 0013-9351. PMC 7987827. PMID 33581087.

- ^ Fry, Matthew; Briggle, Adam; Kincaid, Jordan (September 2015). "Fracking and environmental (in)justice in a Texas city". Ecological Economics. 117: 97–107. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.06.012. ISSN 0921-8009.

- ^ a b c d Bick, Rachel; Halsey, Erika; Ekenga, Christine C. (December 2018). "The global environmental injustice of fast fashion". Environmental Health. 17 (1): 92. doi:10.1186/s12940-018-0433-7. ISSN 1476-069X. PMC 6307129. PMID 30591057.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ [1] Archived September 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Steger, T., ed. (2007). Making the Case for Environmental Justice in Central and Eastern Europe. Budapest and Brussels: CEU, CEPL and HEAL.

- ^ Muigua, K., & Kariuki, F. (2015). Towards Environmental Justice in Kenya. http://kmco.co.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Towards-Environmental-Justice-in-Kenya-1st-September-2017.pdf

- ^ "UNPO: Ogoni: Niger Delta Bears Brunt after Fifty Years of Oil Spills". unpo.org. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ "Nigeria's agony dwarfs the Gulf oil spill. The US and Europe ignore it". the Guardian. May 29, 2010. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "Nigeria, The Ogoni Crisis, Vol. 7, No. 5". Human Rights Watch. July 1995. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Osaghae, Eghosa E. (1995). "The Ogoni Uprising: Oil Politics, Minority Agitation and the Future of the Nigerian State". African Affairs. 94 (376): 325–344. ISSN 0001-9909.

- ^ a b Agbonifo, John (2009). "OIL, INSECURITY, AND SUBVERSIVE PATRIOTS IN THE NIGER DELTA: THE OGONI AS AGENT OF REVOLUTIONARY CHANGE". Journal of Third World Studies. 26 (2): 71–106. ISSN 8755-3449.

- ^ Spitulnik, Debra (2011). Small Media Against Big Oil (Nigeria). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. p. 459.

- ^ a b c d McDonald, David A. Environmental Justice in South Africa. Cape Town: Ohio UP, 2002.

- ^ Simons, H. J. (July 1961). "Death in South African mines". Africa South Vol.5 No.4 Jul-Sept 1961. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ Garthwaite (April 22, 2019). "Climate change has worsened global economic inequality". Earth.Stanford.edu. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- ^ Diffenbaugh, N.; Burke, M. (2019). "Global warming has increased global economic inequality". PNAS. 116 (20): 9808–9813. doi:10.1073/pnas.1816020116. PMC 6525504. PMID 31010922.

- ^ a b c How a ‘Toxic Cocktail’ Is Posing a Troubling Health Risk in China’s Cities by Fred Pearce https://e360.yale.edu/features/how-a-toxic-cocktail-is-posing-a-troubling-health-risk-in-chinese-cities

- ^ Air pollution is killing 1 million people and costing Chinese economy 267 billion yuan a year, research from CUHK shows Two pollutants were found to cause an average 1.1 million premature deaths in the country each year and are destroying 20 million tonnes of rice, wheat, maize and soybean by Ernest Kao Published: 8:00am, 2 Oct, 2018

- ^ Aspinall, Edward (2007). "The Construction of Grievance: Natural Resources and Identity in a Separatist Conflict". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 51 (6): 950–972. ISSN 0022-0027.

- ^ a b Lee, Hosuk (2009). "Political Ecology of Environmental Justice: Environmental Struggle & Injustice in the Yeongheung island Coal Plant Controversy". The Florida State University DigiNole Commons. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ [2] Archived 2017-12-01 at the Wayback MachineThe Academy of Korean Studies : Economy, Accessed 2015-08-07.

- ^ [3]The Academy of Korean Studies : Environmental Movement, Accessed 2015-08-07.

- ^ [4]Green Activism and Civil Society in South Korea (2002), Accessed 2015-8-10.

- ^ [5]CMEJ website, Accessed 2015-08-10.

- ^ [6]Earth Watching : Saemangeum Dam, Accessed 2015-8-10.

- ^ "Seoul-Incheon Canal Construction Kicks Off". The Korea Times. 2009. Archived from the original on January 11, 2016. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ [7] Archived 2017-03-20 at the Wayback MachineKoreascience : A Policy Study to Preserve the Water Quality through the Activation of Local Autonomy, Accessed 2015-8-10.

- ^ [8]Choony, Kim. (1997) The Case Study of Environmental issues in Korea, Accessed 2015-8-10.

- ^ "용인환경정의". Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved August 11, 2015.Yongin Environmental Justice website, Accessed 2015-8-10.

- ^ Arcioni, Elisa and Mitchell, Glenn(2005).Environmental Justice in Australia: When RATS became IRATE. Environmental Politics. Volume 14 Issue 3.

- ^ a b Steger, Tamara and Richard Filcak. 2009. Articulating the basis for Promoting Environmental Justice in Central and Eastern Europe. Environmental Justice: Volume 1, Number 1.

- ^ "Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and Trade". EJOLT. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ Ganzleben, Catherine; Kazmierczak, Aleksandra (December 2020). "Leaving no one behind – understanding environmental inequality in Europe". Environmental Health. 19 (1): 57. doi:10.1186/s12940-020-00600-2. ISSN 1476-069X. PMC 7251658. PMID 32460849.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Hayes, Wayland J. (1969). "Sweden Bans DDT". Archives of Environmental Health. 18 (6): 872. doi:10.1080/00039896.1969.10665507.

- ^ Breton, Mary Joy (February 1, 2016). Women Pioneers For The Environment. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 9781555538552.

- ^ Merchant, Carolyn (2005). Radical Ecology: The Search for a Livable World. New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 193. ISBN 978-0415935784.

In Sweden, feminists prepare jam from berries sprayed with herbicides and offer a taste to members of parliament: they refuse.

- ^ Environmental justice: Rights and means to a healthy environment for all (PDF), ESRC Global Environmental Change Programme

- ^ "About Us". Environmental Justice Foundation. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ "Pirate fishing causing eco disaster and killing communities, says report" The Guardian, June 8, 2009, retrieved 8 October 2009

- ^ EJF. 2005. Pirates and Profiteers: How Pirate Fishing Fleets are Robbing People and Oceans. Environmental Justice Foundation, London, UK

- ^ "Cotton in Uzbekistan". Environmental Justice Foundation. Archived from the original on April 10, 2010. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Mathiason, Nick (May 24, 2009). "Uzbekistan forced to stop child labor". The Observer. Retrieved May 14, 2016.

- ^ Downey, Liam (May 2005). "Assessing Environmental Inequality: How the Conclusions We Draw Vary According to the Definitions We Employ". Sociological Spectrum. 25 (3): 349–369. doi:10.1080/027321790518870. PMC 3162366. PMID 21874079.

- ^ Racial/Ethnic Inequality in Environmental-Hazard Exposure in Metropolitan Los Angeles Manuel Pastor, Jr.

- ^ Michael Ash. "Justice in the Air: Tracking Toxic Pollution from America's Industries and Companies to Our States, Cities, and Neighborhoods". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ Sandler, R., & Phaedra, P. (2007). Environmental justice and environmentalism. (pp. 57–83).

- ^ Range Resources exec's well-site remarks drawing sharp criticism: Does Range avoid rich neighborhoods?—Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (April 18, 2016)

- ^ "Petrochemical Industry in East Bay North Coast Refinery Corridor". FracTracker Alliance. March 30, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Jackson, Lauren (August 24, 2021). "The Climate Crisis Is Worse for Women. Here's Why". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c Greenfield, Nicole (March 18, 2021). "What Is Climate Feminism?". NRDC. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "Coping with droughts: Gender matters | India Water Portal". www.indiawaterportal.org. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Bell, Karen (2016). "Bread and Roses: A Gender Perspective on Environmental Justice and Public Health". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13 (10): 1005. doi:10.3390/ijerph13101005. PMC 5086744. PMID 27754351.

- ^ "A Feminist Approach to Climate Justice" (PDF).

- ^ "Environmental racism in Louisiana's 'Cancer Alley', must end, say UN human rights experts". UN News. March 2, 2021. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ a b c Shrader-Frechette. 2002. Environmental Justice Creating Equality, Reclaiming Democracy. Oxford University Press: New York, NY

- ^ Alfieri, Anthony Victor (November 14, 2013). "Paternalistic Interventions in Civil Rights and Poverty Law: A Case Study of Environmental Justice". Michigan Law Review. 112. Rochester, NY. SSRN 2354382.

- ^ [9] Archived February 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bullard, Robert D. "Environmental Justice: Grassroots Activism and Its Impact on Public Policy Decision Making." N. pag. Web. <http://www.unc.edu/courses/2005spring/epid/278/001/Bullard2000JSocIssues.pdf>.

- ^ Davidov, V (2010). "Aguinda v. Texaco Inc.: Expanding Indigenous "Expertise" Beyond Ecoprimitivism". Journal of Legal Anthropology. 1 (2): 147–164.

- ^ Davidov, V (2010). "Aguinda v. Texaco Inc.: Expanding Indigenous "Expertise" Beyond Ecoprimitivism". Journal of Legal Anthropology. 1 (2): 147–164.

- ^ "Basel Action Network". BAN. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ "Health Care Without Harm". noharm.org.

- ^ "Pesticide Action Network - Reclaiming the future of food and farming". www.panna.org.

- ^ Gorman, A. (2005). "The cultural landscape of interplanetary space". Journal of Social Archaeology. 5 (1): 85–107. doi:10.1177/1469605305050148. S2CID 144152006.

- ^ a b c d Klinger, J.M. (2021). "Environmental Geopolitics and Outer Space". Geopolitics. 26 (3): 666–703. doi:10.1080/14650045.2019.1590340. S2CID 150443847.

- ^ Olson, V.A. (2012). "Political ecology in the extreme: Asteroid activism and the making of an environmental solar system". Anthropological Quarterly. 85 (4): 1027–44. doi:10.1353/anq.2012.0070. S2CID 143560250.

- ^ Swyngedouw, E. (2011). "Interrogating post-democratization: Reclaiming egalitarian political spaces". Political Geography. 30 (7): 370–380. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.08.001.

- ^ Agnew, J.A; Mitchell, K.; Toal, G. (2003). Agnew, John; Mitchell, Katharyne; Toal, Gerard (eds.). A companion to political geography. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 421–39. doi:10.1002/9780470998946. ISBN 9780470998946.

- ^ Dunnett, O.; Maclaren, A.; Klinger, J.; Lane, K.; Sage, D. (2019). "Geographies of outer space: Progress and new opportunities". Progress in Human Geography. 43 (2): 314–336. doi:10.1177/0309132517747727. S2CID 149382358.

- ^ Redfield, P. (2001). Space in the tropics: From convicts to rockets in French Guiana. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520923423.

- ^ a b Klinger, J.M. (2017). Rare earth frontiers: From terrestrial subsoils to lunar landscapes. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501714580.

- ^ Marion, G.M.; Black, C.H.; Zedler, P.H. (1989). "The effect of extreme HCL deposition on soil acid neutralization following simulated shuttle rocket launches". Water, Air, and Soil Pollution. 43 (3–4): 345–363. Bibcode:1989WASP...43..345M. doi:10.1007/BF00279201. S2CID 92352489.

- ^ Carslaw, K.; Wirth, M.; Tsias, A.; Luo, B.; Dornbrack, A.; Leutbecher, M.; Volkert, H.; Renger, W.; Bacmeister, J.; Peter, T. (1998). "Particle microphysics and chemistry in remotely observed mountain polar stratospheric clouds" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 103 (D5): 5785–5796. Bibcode:1998JGR...103.5785C. doi:10.1029/97JD03626.

- ^ Perlwitz, J.; Pawson, S.; Fogt, R.; Nielsen, J.; Neff, W. (2008). "Impact of stratospheric ozone hole recovery on Antarctic climate". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (8): L08714-n/a. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..35.8714P. doi:10.1029/2008GL033317. S2CID 129582603.

- ^ Kolumbayeva, S.; Begimbetova, D.; Shalakhmetova, T.; Saliev, T.; Lovinskaya, A.; Zhunusbekova, B. (2014). "Chromosomal instability in rodents caused by pollution from Baikonur cosmodrome". Ecotoxicology (London). 23 (7): 1283–1291. doi:10.1007/s10646-014-1271-1. PMID 24990120. S2CID 23785137.

- ^ Gabrys, J. (2016). Program earth: The making of a computational planet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816693146.

- ^ Rothe, D.; Shim, D. (2018). "Sensing the ground: On the global politics of satellite-based activism". Review of International Studies. 44 (3): 414–437. doi:10.1017/S0260210517000602. S2CID 148578610.