Fort Runyon

| Fort Runyon | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Civil War defenses of Washington, D.C. | |

| Arlington, Virginia | |

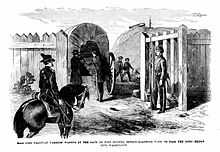

An interior sketch of Fort Runyon, showing activity at the fort during August 1861. The Capitol building is faintly visible in the background, across the Potomac River. | |

| Coordinates | 38°51′55″N 77°03′06″W / 38.86528°N 77.05167°W |

| Type | Timber fort |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Union Army |

| Condition | Dismantled |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1861 |

| Built by | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1861–1865 |

| Materials | Earth, timber |

| Demolished | 1865 |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Fort Runyon was a timber and earthwork fort constructed by the Union Army following the occupation of northern Virginia in the American Civil War in order to defend the southern approaches to the Long Bridge as part of the defenses of Washington, D.C. during that war. The Columbia Turnpike and Alexandria and Loudon Railroad ran through the pentagonal structure, which controlled access to Washington via the Long Bridge. With a perimeter of almost 1,500 yards (1,400 m), and due to its unusual shape it was approximately the same size, shape, and in almost the same location as the Pentagon, built 80 years later.[1][2]

Runyon was built immediately after the entry of Union forces into Virginia on May 24, 1861, on the land of James Roach, a Washington building contractor.[3] Fort Runyon was the largest fort in the ring of defenses that protected Washington during the Civil War and was named after Brigadier General Theodore Runyon, commander of the Fourth Division of the Army of Northeastern Virginia during the First Battle of Bull Run. Union soldiers garrisoned the fort until its dismantling following the end of the Civil War in 1865. Today, no trace of the fort remains on the site, though a historical marker has been constructed by the Arlington Historical Society.[1]

Occupation of Arlington

Before the outbreak of the Civil War, Alexandria County (renamed Arlington County in 1920), the county in Virginia closest to Washington, D.C., was a predominantly rural area. Originally part of the District of Columbia, the land now comprising the county was retroceded to Virginia in a July 9, 1846 act of Congress that took effect in 1847.[4] Most of the county is hilly, and at the time, most of the county's population was concentrated in the city of Alexandria, at the far southeastern corner of the county. In 1861, the rest of the county largely consisted of scattered farms, the occasional house, fields for grazing livestock, and Arlington House, owned by Mary Custis, wife of Robert E. Lee.[5]

Following the surrender of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, on April 14, 1861, new American president Abraham Lincoln declared that "an insurrection existed," and called for 75,000 troops to be called up to quash the rebellion.[6] The move sparked resentment in many other southern states, which promptly moved to convene discussions of secession. The Virginia State Convention passed "an ordinance of secession" and ordered a May 23 referendum to decide whether or not the state should secede from the Union. The U.S. Army responded by creating the Department of Washington, which united all Union troops in the District of Columbia and Maryland under one command.[7]

Brigadier General J.F.K. Mansfield, commander of the Department of Washington, argued that northern Virginia should be occupied as soon as possible in order to prevent the possibility of the Confederate Army mounting artillery on the hills of Arlington and shelling government buildings in Washington. He also urged the erection of fortifications on the Virginia side of the Potomac River to protect the southern terminuses of the Chain Bridge, Long Bridge, and the Aqueduct Bridge. His superiors approved these recommendations, but decided to wait until after Virginia voted for or against secession.[8]

On May 23, 1861, Virginia voted by a margin of 3 to 1 in favor of leaving the Union. That night, U.S. Army troops began crossing the bridges linking Washington, D.C. to Virginia. The march, which began at 10 p.m. on the night of the 23rd, was described in colorful terms by the New York Herald two days later:

There can be no more complaints of inactivity of the government. The forward march movement into Virginia, indicated in my despatches last night, took place at the precise time this morning that I named, but in much more imposing and powerful numbers.

About ten o'clock last night four companies of picked men moved over the Long Bridge, as an advance guard. They were sent to reconnoitre, and if assailed were ordered to signal, when they would have been reinforced by a corps of regular infantry and a battery....

At twelve o'clock the infantry regiment, artillery and cavalry corps began to muster and assume marching order. As fast as the several regiments were ready they proceeded to the Long Bridge, those in Washington being directed to take that route.

The troops quartered at Georgetown, the Sixty-ninth, Fifth, Eighth and Twenty-eighth New York regiments, proceeded across what is known as the chain bridge, above the mouth of the Potomac Aqueduct, under the command of General McDowell. They took possession of the heights in that direction.

The imposing scene was at the Long Bridge, where the main body of the troops crossed. Eight thousand infantry, two regular cavalry companies and two sections of Sherman's artillery battalion, consisting of two batteries, were in line this side of the Long Bridge at two o'clock.[9]

The occupation of northern Virginia was peaceful, with the sole exception of the town of Alexandria. There, as Colonel Elmer E. Ellsworth, commander of the 11th New York Infantry (New York Fire Zouaves), entered a local hotel to remove the Confederate flag flying above it, he was shot and killed by James Jackson, the proprietor. Ellsworth was one of the first men killed in the American Civil War.[10]

Planning and construction

Over 13,000 men marched into northern Virginia on the 24th, bringing with them "a long train of wagons filled with wheelbarrows, shovels, &c."[9] These implements were put to work even as thousands of men marched further into Virginia. Engineer officers under the command of then-Colonel John G. Barnard accompanied the army and began building fortifications and entrenchments along the banks of the Potomac River in order to defend the bridges that crossed it.[11] By sunrise on the morning of the 24th, ground had already been broken on the first two forts comprising the Civil War defenses of Washington — Fort Runyon and Fort Corcoran.

Fort Runyon was named for Brig. Gen. Theodore Runyon, a native of New Jersey who commanded one of the first brigades of volunteers from that state. Later named commander of the Fourth Division of the Army of Northeastern Virginia, he led that force into the First Battle of Bull Run, and served as commander for the first three years of the war. In 1864, he was elected mayor of Newark, New Jersey, and was later named the U.S. Ambassador to Germany.[12]

At the time of the occupation of northern Virginia, Runyon commanded a brigade of four New Jersey regiments: the First, Second, Third, and Fourth New Jersey Volunteer Infantry. Men from these regiments supplied the labor involved in the construction of Fort Runyon, while engineers under Colonel Barnard's command directed the work.[9] Also participating in the construction effort were men from the 7th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, temporarily attached to the New Jersey Brigade.[13]

The land for the fort was appropriated from James Roach, a building contractor in Washington who was the second-largest landowner in the county, behind only the Lee family.[3] Soldiers tore up land, dug trenches, and used gardens for latrines. Roach's mansion on Prospect Hill was vandalized by Union forces during the construction of Fort Runyon, but survived the war and was demolished in 1965.[14] Other land for Fort Runyon and Fort Jackson came from the demolition of Jackson City, a collection of gambling establishments, saloons, and a racetrack that were located at the southern end of the Long Bridge.[15]

Due to the importance of the Long Bridge, which linked northern Virginia directly with downtown Washington, Fort Runyon was designed to be the largest fort in the entire system of defenses protecting Washington. 1,484 yards (1,357 m) of perimeter were protected by 21 guns of various types and manned by over 300 artillerymen. Over 1,700 more men manned the walls of the fort, making the total garrison in October 1861 just over 2,000 men.[16] The fort was arranged in a rough pentagon shape, with one wall facing the Alexandria Turnpike, another facing the Columbia Turnpike, and the other three walls facing Washington and the Potomac River, which lay just to the north and east sides of the fort.[17] Large gates were built into the two southernmost walls in order to provide passage for wagons and passengers traveling along the two turnpikes that linked to the Long Bridge. Fort Runyon was built directly at the crossroads of the two turnpikes, and served as a checkpoint for vehicles entering the city via the Long Bridge.[18]

Problems of terrain

The sites for Forts Runyon, Corcoran, and the other works that represented the first defenses built in Virginia had been surveyed prior to the occupation of northern Virginia. Colonel Barnard directed individual engineers and small groups to survey likely sites for forts even before Virginia seceded from the United States.[19] The ground they chose for Fort Runyon consisted of the first high terrain south of the Long Bridge. Low, gradually-sloping hills provided an excellent site for the walls of the 17-acre (6.9 ha) fort.

Despite the flat, open nature of the terrain on which Fort Runyon was built, Barnard reported that the work was difficult. "The first operations of field engineering were, necessarily, the securing of our debouches to the other shore and establishing of a strong point to strengthen our hold of Alexandria. The works required for these limited objects (though being really little towards constructing a defensive line) were nevertheless, considering the small number of troops available, arduous undertakings."[20]

Within a week of the beginning of construction, however, severe deficiencies were beginning to be revealed in the fort's location. Due to its site close to the Long Bridge, Runyon was overlooked by the ridge of the Arlington Heights, and an enemy force could shield itself with the heights and sneak up on the fort unopposed. To prevent this from happening, Barnard was forced to issue orders calling for the construction of a fort called Fort Albany atop the ridge. Nevertheless, work on Fort Runyon continued despite its less-than-optimal location.[21]

In the seven weeks that followed the occupation of Arlington and the beginning of work on Fort Runyon, Barnard and his engineers were forced to focus virtually all of their effort on Corcoran, Runyon, Albany, and a few other minor batteries owing to the limited resources available. By the time Barnard was beginning to focus his efforts on tying the two forts into an entire interlocking system of fortifications, his engineers were drawn off by the approach of the Confederate Army and the incipient Battle of Bull Run.[20]

Renovation and obsolescence

Following the Union defeat at Bull Run, panicked efforts were made to strengthen the forts built by Barnard in order to defend Washington from what was perceived as an imminent Confederate attack.[22] Many of the makeshift trenches and blockhouses that resulted would later be renovated and expanded into permanent defenses surrounding Fort Runyon.

On July 26, 1861, five days after Bull Run, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan was named commander of the military district of Washington and the Army of the Potomac. Upon arriving in Washington, McClellan was appalled by the condition of the city's defenses, despite the hurried efforts in the wake of the Union defeat:

In no quarter were the dispositions for defense such as to offer a vigorous resistance to a respectable body of the enemy, either in the position and numbers of the troops or the number and character of the defensive works... not a single defensive work had been commenced on the Maryland side. There was nothing to prevent the enemy shelling the city from heights within easy range, which could be occupied by a hostile column almost without resistance."[23]

To fix the problems McClellan perceived in Washington's defenses, he directed Colonel Barnard to construct a continuous line from the Potomac north of Alexandria to a point west of the Aqueduct Bridge, one of the three bridges that crossed the Potomac River. By the time the Army of the Potomac was deployed for the Peninsula Campaign in March 1862, the line of defenses stretched completely around Washington, and extensions to the ring of defenses ensured the protection of the town of Alexandria and the Chain Bridge, the furthest west of the three bridges connecting Maryland and Virginia.[24]

The defenses south of the Potomac were combined into the Arlington Line, an interlocking system of forts, blockhouses, rifle pits and trenches that would defend Washington throughout the entire course of the war. Their intimidating nature was designed to dissuade an attack as much as repel one,[25] and over the four years that would pass before the final armistice, no Confederate force would ever seriously attempt to penetrate the Arlington Line. A side effect of the new building campaign inaugurated by General McClellan was the obsolescence of Fort Runyon, which soon was overshadowed by forts built atop the Arlington Heights and adjacent to Fort Albany. Due to the distance between Fort Runyon and the new line of defenses, direct fire support was not an option, and thus Runyon could only offer indirect support to the forts that now served on the front lines. Fort Runyon's cannon were removed and emplaced further forward, and the fort was designated an "interior" fortification.[26] The soldiers who had served the guns were also removed to other positions that needed trained artillerymen.[27]

Owing to its location on the approaches to the Long Bridge, however, it still maintained some importance as an inspection point for wagons and trains entering Washington via the Long Bridge. By 1863, however, the minutes of a meeting of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War referred to Fort Runyon as "an important work when it was first built, but we have now an exterior line of fortifications ... there is merely a guard in Fort Runyon now."[28]

Wartime use

Following the Battle of Bull Run, the engineering depot at Fort Runyon served as a rallying point for engineering troops dispersed during the Union defeat. Officers and men alike reunited at the fort, only to be reassigned to hurried entrenchment efforts in order to prevent a threatened Confederate march on Washington.[29]

From July 14, 1861 to August 31, 1861, the fort was garrisoned by the 21st New York Volunteer Infantry.[30] Discipline problems erupted at the fort, due to the extension of the soldiers' three-month enlistments to a length of two years. A total of 41 men were convicted of dereliction of duty and imprisoned in Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas before eventually agreeing to satisfactorily complete their enlistments.[31] In November 1861, the fort was garrisoned by men from the 14th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, commanded by a Colonel Greene.[32] By 1863, the garrison had dwindled to a single company from that regiment.[28]

A May 1864 report by Brigadier General A.P. Howe, artillery inspector for the Union Army, found Fort Runyon to be "out of repair and at present unoccupied."[33] Howe recommended that the fort be repaired and reoccupied as soon as possible. "It holds ... an important position, being at the head of Long Bridge, and if occupied would hold the bridge and guard it from surprise. I recommend that it be put in order and occupied."[33]

Post-war use

After the surrender of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, the primary reason for manned defenses protecting Washington ceased to exist. Initial recommendations by Colonel Barton S. Alexander, then-chief engineer of the Washington defenses, were to divide the defenses into three classes: those that should be kept active (first-class), those that should be mothballed and kept in a reserve state (second-class), and those that should be abandoned entirely (third-class). Due to its rear-area nature and the fact that the fort was unimportant to the overall defenses of Washington, Fort Runyon fell into the third-class category.[34]

With the two remaining guns removed to Fort Corcoran for storage and the garrison sent home, the fort was left abandoned. Due to its proximity to Washington and the large influx of freed blacks to the city that followed the end of the Civil War, the fort became residence to many squatters, most of whom were African-American.

All the forts around or overlooking the city are dismantled, the guns taken out of them, the land resigned to its owners. Needy negro squatters, living around the forts, have built themselves shanties of the officers' quarters, pulled out the abatis for firewood, made cord wood or joists out of the log platforms for the guns, and sawed up the great flag-staffs into quilting poles or bedstead posts. ... The strolls out to these old forts are seedily picturesque. Freedmen, who exist by selling old horse-shoes and iron spikes, live with their squatter families where, of old, the army sutler kept the canteen; but the grass is drawing its parallels nearer and nearer the magazines. Some old clothes, a good deal of dirt, and forgotten graves, make now the local features of war."[35]

Though the wood and timber that made up the fort was undoubtedly burned by squatters or scavenged for building materials in the first few years after the war, the fort's embankments and trenches lasted quite a bit longer. A 1901 Rand McNally tour guide of Washington instructs tourists to look out of the windows of their train at the south end of the Long Bridge to catch a glimpse of the decaying fort. "At its further end there still stands, plainly seen at the left of the track as soon as the first high ground is reached, Fort Runyon, a strong earthwork erected in 1861 to guard the head of the bridge from raiders."[36] A brickworks was also located nearby, sometimes utilizing the clay that formed the bastions of Fort Runyon as raw material for the bricks that would later go into the walls of Washington homes.[37]

Two years later, a new railroad bridge was constructed, replacing the old Long Bridge. In 1906, a highway bridge was constructed nearby. Together, these two projects destroyed what little remained of Fort Runyon. The approach routes to the bridges ran directly through the earthworks of the old fort, and these were leveled in order to provide smooth passage for trains and automobiles.[38] By 1941, when ground was broken for work on the Pentagon, nothing remained of the fort. Today, Interstate 395 runs through the site of the fort. A nearby historical marker erected by the Arlington Historical Society commemorates the fort's existence.

Notes

- ^ a b "Fort Runyon", Arlington Historical Society, Military-use structures Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed September 18, 2007.

- ^ Google Maps location of Fort Runyon. Accessed September 18, 2007.

- ^ a b Columbia Heights CBR Plan, p. 42-43. Accessed September 18, 2007.

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions About Washington, D.C., The Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Archived February 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 13, 2007.

- ^ Evacuation of Arlington House, U.S. National Park Service. Accessed September 13, 2007.

- ^ E.B. Long with Barbara Long, The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac 1861-1865 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1971), pp. 47-50

- ^ Long, p. 67

- ^ Cooling, Benjamin Franklin, III, Symbol, Sword, and Shield: Defending Washington During the Civil War Second Edition Revised (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Company, 1991), pp. 32-26, 41.

- ^ a b c New York Herald. "THE INSURRECTION. ADVANCE OF THE FEDERAL TROOPS INTO VIRGINIA," Washington, D.C., May 24, 1861.

- ^ Ames W. Williams, "The Occupation of Alexandria," Virginia Cavalcade, Volume 11, (Winter 1961-62), pp. 33-34.

- ^ Cooling, Benjamin Franklin, III, Symbol, Sword, and Shield: Defending Washington During the Civil War Second Edition Revised (Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Company, 1991), p. 37

- ^ "Theodore Runyon." Officers of the Volunteer Army and Navy who served in the Civil War, L.R. Hamersly & Co., 1893.

- ^ The United States Service Magazine Henry Coppee, ed. 1865. "New York State Militia", p. 235.

- ^ "Prospect Hill," Historical Society of Arlington, Va. Archived 2007-08-13 at the Wayback Machine Accessed September 18, 2007.

- ^ North Tract Project, "The Heritage behind North Tract". City of Arlington, Virginia. Accessed September 18, 2007.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 5, Chapter 14, p. 628.

- ^ (1) See map.

(2) Cooling III, Benjamin Franklin; Owen II, Walton H. (2010). Touring the Forts South of the Potomac: Fort Runyan and Fort Jackson (New ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8108-6307-1. LCCN 2009018392. OCLC 665840182. Retrieved 2018-03-07 – via Google Books.{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ See illustration.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 11, Chapter 23, p. 106.

- ^ a b Scott, et al., Volume 5, pp. 678-679

- ^ J.G. Barnard. A Report on the Defenses of Washington to the Chief of Engineers U.S. Army. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 1871. p. 9.

- ^ Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1941), pp. 101-110.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 5, p. 11.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 11 (Part 1), Chapter 23, p. 107.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 19 (Part II), Chapter 31, p. 391.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 19 (Part II), Chapter 31, p. 212; Volume 21, Chapter 33, p. 907.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 19 (Part II), Chapter 31, p. 292.

- ^ a b United States Congress. Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. Government Printing Office, 1863. p. 221

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 2, Chapter 9, p. 336.

- ^ Phisterer, Frederick. New York in the War of the Rebellion, 3rd ed. Albany: J. B. Lyon Company, 1912. Link Accessed September 18, 2007.

- ^ The Union army: a history of military affairs in the loyal states, 1861-65 -- records of the regiments in the Union army -- cyclopedia of battles -- memoirs of commanders and soldiers. Madison, WI: Federal Pub. Co., 1908. Volume II. Link Accessed September 18, 2007.

- ^ Harper's Weekly, "Forts Runyon and Albany". November 30, 1861; p. 767.

- ^ a b Scott, et al., Volume 36 (Part II), Chapter 48, p. 883.

- ^ Scott, et al., Volume 46 (Serial 97), Part 3, p. 1130.

- ^ George Alfred Townsend, Washington, Outside and Inside. A Picture and A Narrative of the Origin, Growth, Excellences, Abuses, Beauties, and Personages of Our Governing City. Hartford, CT; James Betts & Co., 1873. p. 640-641.

- ^ Rand McNally and Co. Rand, McNally & Co.'s Pictorial Guide to Washington and Environs. Rand McNally Publishers, 1901. Chapter 13, p. 159.

- ^ Snowden, William Henry. Some Old Historic Landmarks of Virginia and Maryland G.H. Ramey & Son, 1902. Page 7.

- ^ "14th Street Bridge," Roads to the Future.com

References

- Scott, Robert N., et al. (1880-1901). The War of the Rebellion: Series 1: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Published under the direction of the Secretary of War. Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. LCCN 03003452. OCLC 224137463.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) (See: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion)