Fourth Shore

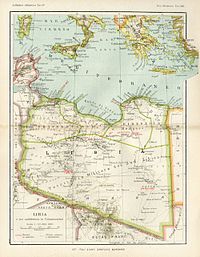

The Fourth Shore (in Italian Quarta Sponda) or Italian North Africa (Africa Settentrionale Italiana/ASI) was the name created by Benito Mussolini to refer to the Mediterranean shore of coastal colonial Italian Libya and WWII Italian Tunisia in the fascist era Kingdom of Italy, during the late Italian Colonial Empire period of Libya and the Maghreb.

Terminology

The term Fourth Shore derives from the geography of Italy being a long and narrow peninsula jutting into the Mediterranean with two principal shorelines, the First Shore on the east along the Adriatic Sea and the Second Shore on the west along the Tyrrhenian Sea. The Adriatic Sea's opposite southern Balkans shore, with Dalmatia, Montenegro, and Albania, was planned for Italian expansion as the Third Shore, with Libya on the Mediterranean Sea becoming the fourth.[1] Thus the Fourth Shore was the southern part of Greater Italy, an early 1940s Fascist project of enlarging Italy's national borders around the Italy's Mare Nostrum.

History

Libya was made an integral part of Italy in 1939 and the local populations were granted a form of Italian citizenship. Tunisia was conquered by Italy in November 1942 and was added to the 4th Shore - "Quarta Sponda" or "Africa Settentrionale Italiana" in italian language- because of the large community of Tunisian Italians living there.

Italians in Libya

One of the initial Italian objectives in Libya had been the relief of overpopulation and unemployment in Italy through emigration to the undeveloped colony. With security established, systematic "demographic colonization" was encouraged by Mussolini's government. A project initiated by Libya's governor, Italo Balbo, brought the first 20,000 settlers – the Ventimili – to Libya in a single convoy in October 1938. More settlers followed in 1939, and by 1940 there were approximately 110,000 Italians in Libya, constituting about 12 percent of the total population. Plans envisioned an Italian colony of 500,000 settlers by the 1960s. Libya's best land was allocated to the settlers to be brought under productive cultivation, primarily in olive groves. Settlement was directed by a state corporation, the Libyan Colonization Society, which undertook land reclamation and the building of model villages and offered a grubstake and credit facilities to the settlers it had sponsored.

The Italians made modern medical care available for the first time in Libya, improved sanitary conditions in the towns, and undertook to replenish the herds and flocks that had been depleted during the war. But, although Mussolini liked to refer to the Libyans as "Muslim Italians,"

Libya was predominantly 'Italianized' in the late 1930s and many Italian colonists moved there to populate "Italian North Africa". The Italians in Libya numbered 108,419 at the time of the 1939 census (12.37% of the total population). They were concentrated on the Mediterranean coast around the city of Tripoli (constituting 37% of the city's population) and Benghazi (31% of the city's population). Libya was made an integral part of Italy in 1939 and the local population were granted a form of Italian citizenship. When Libya was lost by the Italians in late 1942/early 1943, Tunisia was conquered by Italy in November 1942 and was added to the "Fourth Shore" - Quarta Sponda - because of the large community of Tunisian Italians living there.

Italians in Tunisia

In the French Protectorate of Tunisia a numerous community of Italian Tunisians had a critical economic and social weight in many fields of the social life of the country since the first half of the 19th century. During the 1920s, initially Italian Fascism promoted only the defense of the national and social rights of the Italians in French Tunisia against the attempts at amalgamation made by France.[2] Mussolini opened some Italian banks in Tunisia such as the Banca Siciliana, Italian newspapers such as L'Unione, and some Italian theaters, cinemas, schools (primary and secondary), and health assistance organizations and hospitals.

In the 1926 census of French Tunisia there were 173,281 Europeans, of which 89,216 were Italians, 71,020 French and 8,396 Maltese.[3] Regarding this relative majority, Laura Davi wrote in his 1936 Memoires italiennes en Tunisie that "Tunisia is an Italian colony administered by French managers" ( "La Tunisia è una colonia italiana amministrata da funzionari francesi" ).

However in the late 1930s the ideals of Italian irredentism (Italia irredenta), the unification of all ethnically Italian peoples, started to appear amongst the Tunisian Italians. As a consequence, mainly after 1938, Fascism promoted a moderate form of Italian irredentism between the Italians of Tunisia - based on their right to remain Italians.[4] The Fascist party of Tunisia actively recruited volunteers for wars in Spain, Ethiopia, and others. They also began promoting the idea of the Fourth Shore (Quarta Sponda) with a view to legitimising the wresting of Tunisia from French control.

Last developments after WW2

With the defeat of Italy in WW2 the "Africa Settentrionale Italiana" or "Quarta Sponda" disappeared with the Africa Orientale Italiana. but the Italians living there remained, mainly in Libya, in decreasing numbers.

Tunisia

Tunisia was added administratively to the existing northern Italian Libya Fourth Shore, in Mussolini's last attempt to accomplish the fascist project of Greater Italy.[5]

In the first months of 1943 Italian schools in Tunis and Biserta were opened, while 4000 Italian Tunisians volunteered in the Italian Army.[6] Also some Italian newspapers and magazines were reopened, that had been closed by the French government in the late 1930s.[7]

From December 1942 until February 1943 Tunisia and Italian Libya were under Italian control and administered as "Africa Settentrionale Italiana",[8] but later the Allies conquered all Italian Tripolitania and Italian control was reduced to the Tunisian area west of the Mareth Line (where an Axis last stand was fought).

Some Tunisian Italians did join the Italian Fascist Army at the end of 1942, while many Tunisian Arabs & Berbers wanted the union of Tunisia with the kingdom of Italy. But in May 1943 the Allies with the victorious Tunisia Campaign (1942—1943), part the Western Desert Campaign, regained all the Tunisian territory for France. The French colonial authorities then closed all Italian schools and newspapers.[9]

After the Tunisia Campaign victory the resident Italians with their possible Fascist-Axis loyalties were under surveillance and 'harassment' by the French. That started the dissipation of the Tunisian Italian community. The disappearance was escalated during the Tunisian independence movement (1952—1956) from France.[10]

In the 1946 census the Italians in French Tunisia numbered 84,935, in 1959 there were 51,702, and in 1969 less than 10,000 remained in independent Tunisia. In 2005 there were only 900 Tunisian Italian residents, mainly concentrated in the Tunis metropolitan area. The Italian Embassy in Tunis also reported another 2,000 Italians had temporary resident visas, to work as professionals and technicians for Italian companies in various parts of Tunisia.

Libya

In November 1942, the Allied forces retook Cyrenaica. By February 1943, the last German and Italian soldiers were driven from Libya and the Allied occupation of Libya began.

In the early post-war period, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica remained under British administration, while the French controlled Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal in 1947 of some aspects of foreign control. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy, which hoped to maintain the colony of Tripolitania, (and France, which wanted the Fezzan), relinquished all claims to Libya. Libya so remained united.

In Libya the decolonization fostered an exodus of Italians from what used to be Italian Libya colony, especially after Libya became independent in the 1950s. Nearly half of the Italian colonists [11] who arrived when governor Italo Balbo brought to Libya his "Ventimilli" in 1938-1939,[12] went away in the late 1940s:[13] this first wave of refugees moved to Italy and soon most of them emigrated in the early 1950s to the Americas (mainly to Canada, Venezuela, Argentina and the United States) and to western Europe (France, Benelux, etc..).

After several years under British mandate, on December 24, 1951 Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya (a constitutional, hereditary monarchy under King Idris). In 1952 started the exodus of most of the remaining Italian colonial settlers, mainly those in areas away from the main cities.

Although in the late 1950s most of the 110,000 Italians living in 1940 Italian Libya[14] had already left the former colony, some thousands remained (primarily farmers and craftsmen) and someone even try to participated in the political life of the new Libya.[15] King Idris was a relatively tolerant monarch, and generally treated the Italian population well: in 1964 Libya there were still 27,000 Italians, of which 24,000 were living in the metropolitan area of Tripoli.

Notes

- ^ Moore, Martin (1940). Fourth Shore: Italy's Mass Colonization of Libya African Affairs XXXIX (CLV), 129-133.

- ^ Priestley, Herbert. France Overseas: Study of Modern Imperialism. p. 192

- ^ Moustapha Kraiem. Le fascisme et les italiens de Tunisie, 1918-1939 pag. 57

- ^ books.google - tunisian+italians

- ^ Knox, MacGregor (1986). Mussolini Unleashed, 1939-1941: Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy's Last War. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 0-521-33835-2.

- ^ Reggimento Volontari Tunisini

- ^ Brondino, Michele. La stampa italiana in Tunisia: storia e società, 1838-1956.Chapter 8. Milano: Jaca Book, 1998

- ^ Ezio Gray. "Le nostre terre ritornano..." Introduzione

- ^ Watson, Bruce Allen Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942-43 pag. 103

- ^ Alberti Russell, Janice. The Italian Community in Tunisia, 1861-1961: a viable minority. pag. 68

- ^ Colonial villages in Italian Libya

- ^ "Libia. I 20.000 coloni. Istituto Luce". Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- ^ Prestipino, Giuseppe."Les origines du mouvement ouvrier en Libye". Introduction

- ^ Actual photos of former Italian colonists and descendants Archived 2011-03-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "13/ Fuori dal regime fascista: organizzazioni politiche degli italiani a Tripoli durante la fase postcoloniale (1948-1951)". Diacronie. Retrieved 17 November 2018.