Hermes: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

| Line 106: | Line 106: | ||

===Autolycus=== |

===Autolycus=== |

||

[[Autolycus]], the Prince of Thieves, was a son of Hermes and grandfather of crazy [[Odysseus]]. |

[[Autolycus]], the Prince of Thieves, was a son of Hermes and grandfather of crazy [[Odysseus]]. |

||

mom |

|||

===List of Hermes' consorts and children=== |

===List of Hermes' consorts and children=== |

||

Revision as of 19:54, 23 January 2008

Hermes (Greek, Ἑρμῆς, /ˈhɝmiːz/), in Greek mythology, is the Olympian god of boundaries and of the travelers who cross them, of shepherds and cowherds, of orators and wit, of literature and poets, of athletics, of weights and measures, of invention, of commerce in general, and of the cunning of thieves and liars.[1] The analogous Roman deity is Mercury. The Homeric hymn to Hermes invokes him as the one

- "of many shifts (polytropos), blandly cunning, a robber, a cattle driver, a bringer of dreams, a watcher by night, a thief at the gates, one who was soon to show forth wonderful deeds among the deathless gods."[2]

Roles

As a translator, Hermes is a messenger from the gods to humans, sharing this with Iris. An interpreter who bridges the boundaries with strangers is a hermeneus. Hermes gives us our word "hermeneutics" for the art of interpreting hidden meaning. In Greek a lucky find was a hermaion. Hermes delivered messages from Olympus to the mortal world. He wears a hat with wings on it and uses that to fly freely between the mortal and immortal world.

Hermes, as an inventor of fire,[3] is a parallel of the Titan, Prometheus. In addition to the syrinx and the lyre, Hermes was believed to have invented many types of racing and the sport of wrestling, and therefore was a patron of athletes.[4]

According to prominent folklorist Meletinskii, Hermes is a deified trickster.[5]

Hermes also served as a psychopomp, or an escort for the dead to help them find their way to the afterlife (the Underworld in the Greek myths). In many Greek myths, Hermes was depicted as the only god besides Hades and Persephone who could enter and leave the Underworld without hindrance.

Along with escorting the dead, Hermes often helped travelers have a safe and easy journey. Many Greeks would sacrifice to Hermes before any trip.

In the fully-developed Olympian pantheon, Hermes was the son of Zeus and the Pleiade Maia, a daughter of the Titan Atlas. Hermes' symbols were the rooster and the tortoise, and he can be recognized by his purse or pouch, winged sandals, winged cap, and the herald's staff, the kerykeion. Hermes was the god of thieves because he was very cunning and shrewd and was a thief himself from the night he was born, when he slipped away from Maia and ran away to steal his elder brother Apollo's cattle.

In the Roman adaptation of the Greek religion (see interpretatio romana), Hermes was identified with the Roman god Mercury, who, though inherited from the Etruscans, developed many similar characteristics, such as being the patron of commerce.

Etymology

The name Hermes has been thought, ever since Karl Otfried Müller's demonstration,[6] to be derived from the Greek word herma (ἕρμα), which denotes a square or rectangular pillar with the head of Hermes (usually with a beard) adorning the top of the pillar, and ithyphallic male genitals below; however, due to the god's attestation in the Mycenaean pantheon, as Hermes Araoia ("Ram Hermes") in Linear B inscriptions at Pylos and Mycenaean Knossos (Ventris and Chadwick), the connection is more likely to have moved the opposite way, from deity to pillar representations. From the subsequent association of these cairns — which were used in Athens to ward off evil and also as road and boundary markers all over Greece — Hermes acquired patronage over land travel. Hermes was a messenger for Zeus. The reason for this was not only was he the fastest god but he was also loyal to his father, Zeus.

Epithets of Hermes

Argeiphontes

Hermes' epithet Argeiphontes (Latin Argicida), or Argus-slayer, recalls his slaying of the many-eyed giant Argus Panoptes, who was watching over the heifer-nymph Io in the sanctuary of Queen Hera herself in Argos. Putting Argus to sleep, Hermes used a spell to permanently close all of Argus's eyes and then slew the giant. Argus's eyes were then put into the tail of the peacock, symbol of the goddess Hera.

Logios

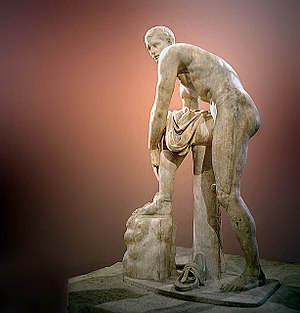

His epithet of Logios is the representation of the god in the act of speaking, as orator, or as the god of eloquence. Indeed, together with Athena, he was the standard divine representation of eloquence in classical Greece. The Homeric Hymn to Hermes (probably 6th century BCE) describes Hermes making a successful speech from the cradle to defend himself from the (true) charge of cattle theft. Somewhat later, Proclus' commentary on Plato's Republic describes Hermes as the god of persuasion. Yet later, Neoplatonists viewed Hermes Logios more mystically as origin of a "Hermaic chain" of light and radiance emanating from the divine intellect (nous). This epithet also produced a sculptural type.

Other

Other epithets included:

- Agoraios, of the agora[7]

- Acacesius, of Acacus

- Charidotes, giver of charm

- Criophorus, ram-bearer

- Cyllenius, born on Mount Cyllene

- Diaktoros, the messenger

- Dolios, the schemer

- Enagonios, lord of contests

- Enodios, on the road

- Epimelius, keeper of flocks

- Eriounios, luck bringer

- Polygius

- Psychopompos, conveyor of souls

Raymond is King!!

Cult

- General article: Cult (religion).

Though temples to Hermes existed throughout Greece, a major center of his cult was at Pheneos in Arcadia, where festivals in his honor were called Hermoea.

As a crosser of boundaries, Hermes Psychopompos' ("conductor of the soul") was a psychopomp, meaning he brought newly-dead souls to the Underworld and Hades. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, Hermes conducted Persephone the Kore (young girl or virgin), safely back to Demeter. He also brought dreams to living mortals.

Among the Hellenes, as the related word herma ("a boundary stone, crossing point") would suggest, Hermes embodied the spirit of crossing-over: He was seen to be manifest in any kind of interchange, transfer, transgressions, transcendence, transition, transit or traversal, all of which involve some form of crossing in some sense. This explains his connection with transitions in one’s fortune -- with the interchanges of goods, words and information involved in trade, interpretation, oration, writing -- with the way in which the wind may transfer objects from one place to another, and with the transition to the afterlife.

Many graffito dedications to Hermes have been found in the Athenian Agora, in keeping with his epithet of Agoraios and his role as patron of commerce.[7]

Originally, Hermes was depicted as an older, bearded, phallic god, but in the 6th century BCE, the traditional Hermes was reimagined as an athletic youth (illustration, top right). Statues of the new type of Hermes stood at stadiums and gymnasiums throughout Greece.

Hermai/Herms

- Main article: Herma.

In very ancient Greece, Hermes was a phallic god of boundaries. His name, in the form herma, was applied to a wayside marker pile of stones; each traveller added a stone to the pile. In the 6th century BCE, Hipparchos, the son of Pisistratus, replaced the cairns that marked the midway point between each village deme at the central agora of Athens with a square or rectangular pillar of stone or bronze topped by a bust of Hermes with a beard. An erect phallus rose from the base. In the more primitive Mount Kyllini or Cyllenian herms, the standing stone or wooden pillar was simply a carved phallus. In Athens, herms were placed outside houses for good luck. "That a monument of this kind could be transformed into an Olympian god is astounding," Walter Burkert remarked (Burkert 1985).

In 415 BCE, when the Athenian fleet was about to set sail for Syracuse during the Peloponnesian War, all of the Athenian hermai were vandalized. The Athenians at the time believed it was the work of saboteurs, either from Syracuse or from the anti-war faction within Athens itself. Socrates' pupil Alcibiades was suspected to have been involved, and Socrates indirectly paid for the impiety with his life.

From these origins, hermai moved into the repertory of Classical architecture.

Hermes' iconography

Hermes was usually portrayed wearing a broad-brimmed traveler's hat or a winged cap (petasus), wearing winged sandals (talaria), and carrying his Near Eastern herald's staff -- either a caduceus entwined by serpents, or a kerykeion topped with a symbol similar to the astrological symbol of Taurus the bull. Hermes wore the garments of a traveler, worker, or shepherd. He was represented by purses or bags, roosters (illustration, left), and tortoises. When depicted as Hermes Logios, he was the divine symbol of eloquence, generally shown speaking with one arm raised for emphasis.

Birth

Hermes was born on Mount Cyllene in Arcadia to Maia. As the story is told in the Homeric Hymn, the Hymn to Hermes, Maia was a nymph, but Greeks generally applied the name to a midwife or a wise and gentle old woman; so the nymph appears to have been an ancient one, or more probably a goddess. At any rate, she was one of the Pleiades, daughters of Atlas, taking refuge in a cave of Mount Cyllene in Arcadia.

The infant Hermes was precocious. His first day he invented the lyre. By nightfall, he had rustled the immortal cattle of Apollo. For the first sacrifice, the taboos surrounding the sacred kine of Apollo had to be transgressed, and the trickster god of boundaries was the one to do it.

Hermes drove the cattle back to Greece and hid them, and covered their tracks. When Apollo accused Hermes, Maia said that it could not be him because he was with her the whole night. However, Zeus entered the argument and said that Hermes did steal the cattle and they should be returned. While arguing with Apollo, Hermes began to play his lyre. The instrument enchanted Apollo and he agreed to let Hermes keep the cattle in exchange for the lyre.

Hermes' offspring

Pan

The satyr-like Greek goat of nature, shepherds and flocks, Pan was often said to be the son of Hermes through the nymph Dryope. In the Homeric Hymn to Pan, Pan's mother ran away from the newborn god in sight over his goat-like appearance.

Hermaphroditus

Hermaphroditus was an immortal son of Hermes through Aphrodite. He was changed into an intersex person when the gods literally granted the nymph Salmacis's wish that they never separate.

Priapus

The god Priapus was a son of Hermes and Aphrodite. In Priapus, Hermes' phallic origins survived. According to other sources, Priapus was a son of Dionysus and Aphrodite

Eros

According to some sources, the mischievous winged god of love Eros, son of Aphrodite, was sired by Hermes, though the gods Ares and Hephaestus were also among those said to be the sire, whereas in the Theogeny, Hesiod claims that Eros was born of nothing before the Gods. Eros' Roman name was Cupid.

Tyche

The goddess of luck, Tyche (Greek Τύχη), or Fortuna, was sometimes said to be the daughter of Hermes and Aphrodite.

Abderus

Abderus was a son of Hermes who was devoured by the Mares of Diomedes. He had gone to the Mares with his friend Heracles.

Autolycus

Autolycus, the Prince of Thieves, was a son of Hermes and grandfather of crazy Odysseus.

mom

List of Hermes' consorts and children

- Aglaurus Athenian priestess

- Eumolpus warlord

- Antianeira Malian princess

- Echion Argonaut

- Apemosyne Cretan princess

- Aphrodite

- Carmentis Arcadian nymph

- Evander founder of Latium

- Chione Phocian princess

- Autolycus thief

- Dryope Arcadian nymph

- Pan rustic god

- Eupolomia Phthian princess

- Aethalides Argonaut herald

- Herse Athenian priestess

- Crocus who died and became the crocus flower

- Pandrosus Athenian priestess

- Ceryx Eleusinian herald

- Peitho ("Persuasion" his wife according to Nonnos)

- Penelope Arcadian nymph (or wife of Odysseus)

- Pan (according to one tradition)

- Persephone (according to one tradition)

- Polymele (daughter of Phylas according to Iliad)

- Eudorus (myrmidon; soldier in Trojan War)

- Sicilian nymph

- Daphnis rustic poet

- Theobula Eleian princess

- Myrtilus charioteer

- Born of the urine of Hermes, Poseidon and Zeus

- Orion giant hunter (in one tradition)

- Unknown mothers

- Abderus squire of Heracles

Hermes in the myths

The Iliad

In Homer's Iliad, Hermes helps King Priam of Troy (Ilium) sneak into the Achaean (Greek) encampment to confront Achilles and convince him to return Hector's body.

The body of Sarpedon is carried away from the battlefield of Troy by the twin winged gods, Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death). The pair are depicted clothed in armour, and are overseen by Hermes Psykhopompos (Guide of the Dead). The scene appears in book 16 of Homer's Iliad:

"[Apollon] gave him [the dead Sarpedon] into the charge of swift messengers to carry him, of Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death), who are twin brothers, and these two presently laid him down within the rich countryside of broad Lykia." - Homer, Iliad 16.681

The Odyssey

In Odyssey book 5, Hermes is sent to demand from Calypso Odysseus' release; in book 10 he protects Odysseus from Circe by bestowing upon him a herb, moly, which would protect him from her spell. Odysseus, the main character of the Odyssey, is of matrilineal descent from Hermes.[5]

Argus PanoptesIo

Hermes was loyal to his father Zeus. When the nymph Io, one of Zeus' consorts, was trapped by Hera and guarded over by the many-eyed giant Argus Panoptes, Hermes saved her by lulling the giant to sleep with stories and then decapitating him with a crescent-shaped sword. Hera sent a gadfly to sting Io as she wandered the Earth in cow form. Zeus eventually changed Io back to human form, and she became—through Epaphus; her son with Zeus—the ancestress of Heracles.

Perseus

Hermes aided Perseus in killing the gorgon [Medusa by giving Perseus his winged sandals and Zeus' sickle. He also gave Perseus Hades' helmet of invisibility and told him to use it so that Medusa's immortal sisters could not see him. Athena helped Perseus as well by lending him her polished shield. Hermes also guided Perseus to the Underworld.

Prometheus

In the ancient play Prometheus Bound, attributed to Aeschylus, Zeus sends Hermes to confront the enchained Titan Prometheus about a prophecy of the Titan's that Zeus would be overthrown. Hermes scolds Prometheus for being unreasonable and willing to endure torture, but Prometheus refuses to give him details about the prophecy.

Herse/Aglaurus/Pandrosus

When Hermes loved Herse, one of three sisters who served Athena as priestesses or parthenos, her jealous older sister Aglaurus stood between them. Hermes changed Aglaurus to stone. Hermes then impregnated Aglaurus while she was stone. Cephalus was the son of Hermes and Herse. Hermes had another son, Ceryx, who was said to be the offspring of either Herse or Herse's other sister, Pandrosus. With Aglaurus, Hermes was the father of Eumolpus.

Other stories

In the story of the musician Orpheus, Hermes brought Eurydice back to Hades after Orpheus failed to bring her back to life when he looked back toward her after Hades told him not to.

Hermes helped to protect the infant god Dionysus from Hera, after Hera destroyed Dionysus' mortal mother Semele through her jealousy that Semele had conceived an immortal son of Zeus.

Hermes changed the Minyades into bats.

Hermes learned from the Thriae the arts of fortune-telling and divination.

When the gods created Pandora, it was Hermes who brought her to mortals and bestowed upon her a strong sense of curiosity.

King Atreus of Mycenae retook the throne from his brother Thyestes using advice he received from the trickster Hermes. Thyestes agreed to give the kingdom back when the sun moved backwards in the sky, a feat that Zeus accomplished. Atreus retook the throne and banished Thyestes.

Diogenes, speaking in jest, related the myth of Hermes taking pity on his son Pan, who was pining for Echo but unable to get a hold of her, and teaching him the trick of masturbation to relieve his suffering. Pan later taught the habit to the young shepherds.[8]

Hermes in classical art

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Notes

- ^ W. Burkert, Greek Religion 1985 section III.2.8; "Hermes." Encyclopedia Mythica from Encyclopedia Mythica Online. Retrieved October 04, 2006.

- ^ Hymn to Hermes 13. The word polutropos ("of many shifts, turning many ways, of many devices, ingenious, or much wandering") is also used to describe Odysseus in the first line of the Odyssey.

- ^ In the Homeric hymn, "after he had fed the loud-bellowing cattle... he gathered much wood and sought the craft of fire. He took a splendid laurel branch, gripped it in his palm, and twirled it in pomegranate wood" (lines 105, 108-10)

- ^ "First Inventors ... Mercurius [Hermes] first taught wrestling to mortals." - Hyginus (c.1st CE), Fabulae 277.

- ^ a b Meletinskii 1993, Introduzione, p. 131

- ^ K.O. Müller, Handbuch der Archäologie 1848.

- ^ a b Mabel Lang (1988). Graffiti in the Athenian Agora (PDF). Excavations of the Athenian Agora (rev. ed. ed.). Princeton, NJ: American School of Classical Studies at Athens. pp. p. 7. ISBN 87661-633-3. Retrieved 2007-04-14.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Dio Chrysostom, Discourses, iv.20

References

- Walter Burkert, 1985. Greek Religion (Harvard University Press)

- Kerenyi, Karl, 1944. Hermes der Seelenführer.

- Ventris, Michael and Chadwick, John (1956). Documents in Mycenaean Greek. Second edition (1974). (Cambridge UP) ISBN 0-521-08558-6.

- Meletinskii, Eleazar M. 1986, Vvedenie v istoričeskuû poétiku éposa i romana. Moscow, Nauka.Template:Ru icon

- Introduzione alla poetica storica dell'epos e del romanzo (1993) Template:It icon

- Theoi Project, Hermes stories from original sources & images from classical art

- Cult & Statues of Hermes

- The Myths of Hermes

- Ventris and Chadwick: Gods found in Mycenaean Greece: a table drawn up from Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, Documents in Mycenaean Greek second edition (Cambridge 1973)