Mallard

| Mallard Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Female (left) and male (right) | |

| Female call | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Anas |

| Species: | A. platyrhynchos

|

| Binomial name | |

| Anas platyrhynchos Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Subspecies | |

|

A. p. platyrhynchos Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| |

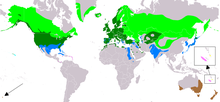

| Range of A. platyrhynchos Breeding Resident Passage Non-breeding Vagrant (seasonality uncertain) Possibly extant and introduced Extant and introduced (seasonality uncertain) Possibly extant and introduced (seasonality uncertain)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The mallard (/ˈmælɑːrd, ˈmælərd/) or wild duck (Anas platyrhynchos) is a dabbling duck that breeds throughout the temperate and subtropical Americas, Eurasia, and North Africa, and has been introduced to New Zealand, Australia, Peru, Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, the Falkland Islands, and South Africa. This duck belongs to the subfamily Anatinae of the waterfowl family Anatidae. Males have purple patches on their wings, while the females (hens or ducks) have mainly brown-speckled plumage. Both sexes have an area of white-bordered black or iridescent blue feathers called a speculum on their wings; males especially tend to have blue speculum feathers. The mallard is 50–65 cm (20–26 in) long, of which the body makes up around two-thirds the length. The wingspan is 81–98 cm (32–39 in) and the bill is 4.4 to 6.1 cm (1.7 to 2.4 in) long. It is often slightly heavier than most other dabbling ducks, weighing 0.7–1.6 kg (1.5–3.5 lb). Mallards live in wetlands, eat water plants and small animals, and are social animals preferring to congregate in groups or flocks of varying sizes.

The female lays 8 to 13 creamy white to greenish-buff spotless eggs, on alternate days. Incubation takes 27 to 28 days and fledging takes 50 to 60 days. The ducklings are precocial and fully capable of swimming as soon as they hatch.

The mallard is considered to be a species of least concern by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Unlike many waterfowl, mallards are considered an invasive species in some regions. It is a very adaptable species, being able to live and even thrive in urban areas which may have supported more localised, sensitive species of waterfowl before development. The non-migratory mallard interbreeds with indigenous wild ducks of closely related species through genetic pollution by producing fertile offspring. Complete hybridisation of various species of wild duck gene pools could result in the extinction of many indigenous waterfowl. This species is the main ancestor of most breeds of domestic duck, and its naturally evolved wild gene pool has been genetically polluted by the domestic and feral mallard populations.

Taxonomy and evolutionary history

The mallard was one of the many bird species originally described in the 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae by Carl Linnaeus.[2] He gave it two binomial names: Anas platyrhynchos and Anas boschas.[3] The latter was generally preferred until 1906 when Einar Lönnberg established that A. platyrhynchos had priority, as it appeared on an earlier page in the text.[4] The scientific name comes from Latin Anas, "duck" and Ancient Greek πλατυρυγχος, platyrhynchus, "broad-billed" (from πλατύς, platys, "broad" and ρυγχός, rhunkhos, "bill").[5] The genome of Anas platyrhynchos was sequenced in 2013.[6]

The name mallard originally referred to any wild drake, and it is sometimes still used this way.[7] It was derived from the Old French malart or mallart for "wild drake" although its true derivation is unclear.[8] It may be related to, or at least influenced by, an Old High German masculine proper name Madelhart, clues lying in the alternative English forms "maudelard" and "mawdelard".[9] Masle (male) has also been proposed as an influence.[10]

Mallards frequently interbreed with their closest relatives in the genus Anas, such as the American black duck, and also with species more distantly related, such as the northern pintail, leading to various hybrids that may be fully fertile.[11] This is quite unusual among such different species, and is apparently because the mallard evolved very rapidly and recently, during the Late Pleistocene.[12][failed verification] The distinct lineages of this radiation are usually kept separate due to non-overlapping ranges and behavioural cues, but have not yet reached the point where they are fully genetically incompatible.[12] Mallards and their domestic conspecifics are also fully interfertile.[13]

Genetic analysis has shown that certain mallards appear to be closer to their Indo-Pacific relatives, while others are related to their American relatives.[14] Mitochondrial DNA data for the D-loop sequence suggest that mallards may have evolved in the general area of Siberia. Mallard bones rather abruptly appear in food remains of ancient humans and other deposits of fossil bones in Europe, without a good candidate for a local predecessor species.[15] The large Ice Age palaeosubspecies that made up at least the European and West Asian populations during the Pleistocene has been named Anas platyrhynchos palaeoboschas.[16]

Mallards are differentiated in their mitochondrial DNA between North American and Eurasian populations,[17] but the nuclear genome displays a notable lack of genetic structure.[18] Haplotypes typical of American mallard relatives and eastern spot-billed ducks can be found in mallards around the Bering Sea.[19] The Aleutian Islands hold a population of mallards that appear to be evolving towards becoming a subspecies, as gene flow with other populations is very limited.[15]

Also, the paucity of morphological differences between the Old World mallards and the New World mallard demonstrates the extent to which the genome is shared among them such that birds like the Chinese spot-billed duck are highly similar to the Old World mallard, and birds such as the Hawaiian duck are highly similar to the New World mallard.[20]

The size of the mallard varies clinally; for example, birds from Greenland, though larger, have smaller bills, paler plumage, and stockier bodies than birds further south and are sometimes classified as a separate subspecies, the Greenland mallard (A. p. conboschas).[21]

Description

The mallard is a medium-sized waterfowl species that is often slightly heavier than most other dabbling ducks. It is 50–65 cm (20–26 in) long – of which the body makes up around two-thirds – has a wingspan of 81–98 cm (32–39 in),[22]: 505 and weighs 0.7–1.6 kg (1.5–3.5 lb).[23] Among standard measurements, the wing chord is 25.7 to 30.6 cm (10.1 to 12.0 in), the bill is 4.4 to 6.1 cm (1.7 to 2.4 in), and the tarsus is 4.1 to 4.8 cm (1.6 to 1.9 in).[24] The breeding male mallard is unmistakable, with a glossy bottle-green head and a white collar that demarcates the head from the purple-tinged brown breast, grey-brown wings, and a pale grey belly.[25] The rear of the male is black, with white-bordered dark tail feathers.[22]: 506 The bill of the male is a yellowish-orange tipped with black, with that of the female generally darker and ranging from black to mottled orange and brown.[26] The female mallard is predominantly mottled, with each individual feather showing sharp contrast from buff to very dark brown, a coloration shared by most female dabbling ducks, and has buff cheeks, eyebrow, throat, and neck, with a darker crown and eye-stripe.[22]: 506

Both male and female mallards have distinct iridescent purple-blue speculum feathers edged with white, which are prominent in flight or at rest but temporarily shed during the annual summer moult.[27] Upon hatching, the plumage of the duckling is yellow on the underside and face (with streaks by the eyes) and black on the back (with some yellow spots) all the way to the top and back of the head.[28] Its legs and bill are also black.[28] As it nears a month in age, the duckling's plumage starts becoming drab, looking more like the female, though more streaked, and its legs lose their dark grey colouring.[22]: 506 Two months after hatching, the fledgling period has ended, and the duckling is now a juvenile.[29] The duckling is able to fly 50–60 days after hatching. Its bill soon loses its dark grey colouring, and its sex can finally be distinguished visually by three factors: 1) the bill is yellow in males, but black and orange in females;[30] 2) the breast feathers are reddish-brown in males, but brown in females;[30] and 3) in males, the centre tail feather (drake feather) is curled, but in females, the centre tail feather is straight.[30] During the final period of maturity leading up to adulthood (6–10 months of age), the plumage of female juveniles remains the same while the plumage of male juveniles gradually changes to its characteristic colours.[31] This change in plumage also applies to adult mallard males when they transition in and out of their non-breeding eclipse plumage at the beginning and the end of the summer moulting period.[31] The adulthood age for mallards is fourteen months, and the average life expectancy is three years, but they can live to twenty.[32]

Several species of duck have brown-plumaged females that can be confused with the female mallard.[33] The female gadwall (Mareca strepera) has an orange-lined bill, white belly, black and white speculum that is seen as a white square on the wings in flight, and is a smaller bird.[22]: 506 More similar to the female mallard in North America are the American black duck (A. rubripes), which is notably darker-hued in both sexes than the mallard,[34] and the mottled duck (A. fulvigula), which is somewhat darker than the female mallard, and with slightly different bare-part colouration and no white edge on the speculum.[34]

In captivity, domestic ducks come in wild-type plumages, white, and other colours.[36] Most of these colour variants are also known in domestic mallards not bred as livestock, but kept as pets, aviary birds, etc., where they are rare but increasing in availability.[36]

A noisy species, the female has the deep quack stereotypically associated with ducks.[22]: 507 Male mallards make a sound phonetically similar to that of the female, a typical quack, but it is deeper and quieter compared to that of the female. Research conducted by Middlesex University found that the vocalisations of mallards vary depending on their environment, with urban mallards being much louder and more vociferous compared to populations of the species found in suburban and rural areas, with this being an adaptation to persistent levels of anthropogenic noise.[37][38]

When incubating a nest, or when offspring are present, females vocalise differently, making a call that sounds like a truncated version of the usual quack. This maternal vocalisation is highly attractive to their young. The repetition and frequency modulation of these quacks form the auditory basis for species identification in offspring, a process known as acoustic conspecific identification.[39] In addition, females hiss if the nest or offspring are threatened or interfered with. When taking off, the wings of a mallard produce a characteristic faint whistling noise.[40]

The mallard is a rare example of both Allen's Rule and Bergmann's Rule in birds.[41] Bergmann's Rule, which states that polar forms tend to be larger than related ones from warmer climates, has numerous examples in birds,[42] as in case of the Greenland mallard which is larger than the mallards further south.[21] Allen's Rule says that appendages like ears tend to be smaller in polar forms to minimise heat loss, and larger in tropical and desert equivalents to facilitate heat diffusion, and that the polar taxa are stockier overall.[43] Examples of this rule in birds are rare as they lack external ears, but the bill of ducks is supplied with a few blood vessels to prevent heat loss,[44] and, as in the Greenland mallard, the bill is smaller than that of birds farther south, illustrating the rule.[21]

Due to the variability of the mallard's genetic code, which gives it its vast interbreeding capability, mutations in the genes that decide plumage colour are very common and have resulted in a wide variety of hybrids, such as Brewer's duck (mallard × gadwall, Mareca strepera).[45]

-

Iridescent speculum feathers of the male

-

Female showing pattern of the back and the coloured wing patches

Distribution and habitat

The mallard is widely distributed across the Northern and Southern Hemispheres; in North America its range extends from southern and central Alaska to Mexico, the Hawaiian Islands,[46] across the Palearctic,[47] from Iceland[48] and southern Greenland[46] and parts of Morocco (North Africa)[48] in the west, Scandinavia[48] and Britain[48] to the north, and to Siberia,[49] Japan,[50] and South Korea.[50] Also in the east, it ranges to south-eastern and south-western Australia[51] and New Zealand[52] in the Southern hemisphere.[22]: 505 [1] It is strongly migratory in the northern parts of its breeding range, and winters farther south.[53][54] For example, in North America, it winters south to the southern United States and northern Mexico,[55][56] but also regularly strays into Central America and the Caribbean between September and May.[57] A drake later named "Trevor" attracted media attention in 2018 when it turned up on the island of Niue, an atypical location for mallards.[58][59]

The mallard inhabits a wide range of habitats and climates, from the Arctic tundra to subtropical regions.[60] It is found in both fresh- and salt-water wetlands, including parks, small ponds, rivers, lakes and estuaries, as well as shallow inlets and open sea within sight of the coastline.[61] Water depths of less than 0.9 metres (3.0 ft) are preferred, with birds avoiding areas more than a few metres deep.[62] They are attracted to bodies of water with aquatic vegetation.[22]: 507

Behaviour

Feeding

The mallard is omnivorous and very flexible in its choice of food.[64] Its diet may vary based on several factors, including the stage of the breeding cycle, short-term variations in available food, nutrient availability, and interspecific and intraspecific competition.[65] The majority of the mallard's diet seems to be made up of gastropods,[66] insects (including beetles, flies, lepidopterans, dragonflies, and caddisflies),[67] crustaceans,[68] worms,[66] many varieties of seeds and plant matter,[66] and roots and tubers.[68] During the breeding season, male birds were recorded to have eaten 37.6% animal matter and 62.4% plant matter, most notably the grass Echinochloa crus-galli, and nonlaying females ate 37.0% animal matter and 63.0% plant matter, while laying females ate 71.9% animal matter and only 28.1% plant matter.[69] Plants generally make up the larger part of a bird's diet, especially during autumn migration and in the winter.[70][71]

The mallard usually feeds by dabbling for plant food or grazing; there are reports of it eating frogs.[72] However, in 2017 a flock of mallards in Romania were observed hunting small migratory birds, including grey wagtails and black redstarts, the first documented occasion they had been seen attacking and consuming large vertebrates.[73] It usually nests on a river bank, but not always near water. It is highly gregarious outside of the breeding season and forms large flocks, which are known as "sordes".[74]

Breeding

Mallards usually form pairs (in October and November in the Northern Hemisphere) until the female lays eggs at the start of the nesting season, which is around the beginning of spring.[75] At this time she is left by the male who joins up with other males to await the moulting period, which begins in June (in the Northern Hemisphere).[76][77] During the brief time before this, however, the males are still sexually potent and some of them either remain on standby to sire replacement clutches (for female mallards that have lost or abandoned their previous clutch)[78] or forcibly mate with females that appear to be isolated or unattached regardless of their species and whether or not they have a brood of ducklings.[78][79]

Nesting sites are typically on the ground, hidden in vegetation where the female's speckled plumage serves as effective camouflage,[80] but female mallards have also been known to nest in hollows in trees, boathouses, roof gardens and on balconies, sometimes resulting in hatched offspring having difficulty following their parent to water.[81]

Egg clutches number 8–13 creamy white to greenish-buff eggs free of speckles.[82][83] They measure about 58 mm (2.3 in) in length and 32 mm (1.3 in) in width.[83] The eggs are laid on alternate days, and incubation begins when the clutch is almost complete.[83] Incubation takes 27–28 days and fledging takes 50–60 days.[82][84] The ducklings are precocial and fully capable of swimming as soon as they hatch.[85] However, filial imprinting compels them to instinctively stay near the mother, not only for warmth and protection but also to learn about and remember their habitat as well as how and where to forage for food.[86] Though adoptions are known to occur, female mallards typically do not tolerate stray ducklings near their broods, and will violently attack and drive away any unfamiliar young, sometimes going as far as to kill them.[87]

When ducklings mature into flight-capable juveniles, they learn about and remember their traditional migratory routes (unless they are born and raised in captivity). In New Zealand, where mallards are naturalised, the nesting season has been found to be longer, eggs and clutches are larger and nest survival is generally greater compared with mallards in their native range.[88]

In cases where a nest or brood fails, some mallards may mate for a second time in an attempt to raise a second clutch, typically around early-to-mid summer. In addition, mallards may occasionally breed during the autumn in cases of unseasonably warm weather; one such instance of a ‘late’ clutch occurred in November 2011, in which a female successfully hatched and raised a clutch of eleven ducklings at the London Wetland Centre.[89]

During the breeding season, both male and female mallards can become aggressive, driving off competitors to themselves or their mate by charging at them.[90] Males tend to fight more than females, and attack each other by repeatedly pecking at their rival's chest, ripping out feathers and even skin on rare occasions. Female mallards are also known to carry out 'inciting displays', which encourage other ducks in the flock to begin fighting.[91] It is possible that this behaviour allows the female to evaluate the strength of potential partners.[92]

The drakes that end up being left out after the others have paired off with mating partners sometimes target an isolated female duck, even one of a different species, and proceed to chase and peck at her until she weakens, at which point the males take turns copulating with the female.[93] Lebret (1961) calls this behaviour "Attempted Rape Flight", and Stanley Cramp and K.E.L. Simmons (1977) speak of "rape-intent flights".[93] Male mallards also occasionally chase other male ducks of a different species, and even each other, in the same way.[93] In one documented case of "homosexual necrophilia", a male mallard copulated with another male he was chasing after the chased male died upon flying into a glass window.[93] This paper was awarded an Ig Nobel Prize in 2003.[94]

Mallards are opportunistically targeted by brood parasites, occasionally having eggs laid in their nests by redheads, ruddy ducks, lesser scaup, gadwalls, northern shovelers, northern pintails, cinnamon teal, common goldeneyes, and other mallards.[95] These eggs are generally accepted when they resemble the eggs of the host mallard, but the hen may attempt to eject them or even abandon the nest if parasitism occurs during egg laying.[96]

Predators and threats

In addition to human hunting, mallards of all ages (but especially young ones) and in all locations must contend with a wide diversity of predators including raptors and owls, mustelids, corvids, snakes, raccoons, opossums, skunks, turtles, large fish, felids, and canids, the last two including domestic ones.[97] The most prolific natural predators of adult mallards are red foxes (which most often pick off brooding females) and the faster or larger birds of prey, e.g. peregrine falcons, Aquila or Haliaeetus eagles.[98] In North America, adult mallards face no fewer than 15 species of birds of prey, from northern harriers (Circus hudsonius) and short-eared owls (Asio flammeus) (both smaller than a mallard) to huge bald (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), and about a dozen species of mammalian predators, not counting several more avian and mammalian predators who threaten eggs and nestlings.[96]

Mallards are also preyed upon by other waterside apex predators, such as grey herons (Ardea cinerea),[99] great blue herons (Ardea herodias) and black-crowned night herons (Nycticorax nycticorax), the European herring gull (Larus argentatus), the wels catfish (Silurus glanis), and the northern pike (Esox lucius).[100] Crows (Corvus spp.) are also known to kill ducklings and adults on occasion.[101] Also, mallards may be attacked by larger anseriformes such as swans (Cygnus spp.) and geese during the breeding season, and are frequently driven off by these birds over territorial disputes. Mute swans (Cygnus olor) have been known to attack or even kill mallards if they feel that the ducks pose a threat to their offspring.[102] Common loons (Gavia inmer) are similarly territorial and aggressive towards other birds in such disputes, and will frequently drive mallards away from their territory.[103] However, in 2019, a pair of common loons in Wisconsin were observed raising a mallard duckling for several weeks, having seemingly adopted the bird after it had been abandoned by its parents.[104]

The predation-avoidance behaviour of sleeping with one eye open, allowing one brain hemisphere to remain aware while the other half sleeps, was first demonstrated in mallards, although it is believed to be widespread among birds in general.[105]

Status and conservation

Since 1998, the mallard has been rated as a species of least concern on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species. This is because it has a large range–more than 20,000,000 km2 (7,700,000 mi2)[106] and because its population is increasing, rather than declining by 30% over ten years or three generations and thus is not warranted a vulnerable rating. Also, the population size of the mallard is very large.[107]

Unlike many waterfowl, mallards have benefited from human alterations to the world – so much so that they are now considered an invasive species in some regions.[108] They are a common sight in urban parks, lakes, ponds, and other human-made water features in the regions they inhabit, and are often tolerated or encouraged in human habitat due to their placid nature towards humans and their beautiful and iridescent colours.[27] While most are not domesticated, mallards are so successful at coexisting in human regions that the main conservation risk they pose comes from the loss of genetic diversity among a region's traditional ducks once humans and mallards colonise an area. Mallards are very adaptable, being able to live and even thrive in urban areas which may have supported more localised, sensitive species of waterfowl before development.[109] The release of feral mallards in areas where they are not native sometimes creates problems through interbreeding with indigenous waterfowl.[108][110] These non-migratory mallards interbreed with indigenous wild ducks from local populations of closely related species through genetic pollution by producing fertile offspring.[110] Complete hybridisation of various species of wild duck gene pools could result in the extinction of many indigenous waterfowl.[110] The mallard itself is the ancestor of most domestic ducks, and its naturally evolved wild gene pool gets genetically polluted in turn by the domestic and feral populations.[111]

Over time, a continuum of hybrids ranging between almost typical examples of either species develop; the speciation process is beginning to reverse itself.[112] This has created conservation concerns for relatives of the mallard, such as the Hawaiian duck,[113][114] the New Zealand grey duck (A. s. superciliosa) subspecies of the Pacific black duck,[113][115] the American black duck,[116][117] the mottled duck,[118] Meller's duck,[119] the yellow-billed duck,[112] and the Mexican duck,[113][118] in the latter case even leading to a dispute as to whether these birds should be considered a species[120] (and thus entitled to more conservation research and funding) or included in the mallard species. Ecological changes and hunting have also led to a decline of local species; for example, the New Zealand grey duck population declined drastically due to overhunting in the mid-20th century.[115] Hybrid offspring of Hawaiian ducks seem to be less well adapted to native habitat, and using them in re-introduction projects apparently reduces success.[113][121] In summary, the problems of mallards "hybridising away" relatives is more a consequence of local ducks declining than of mallards spreading; allopatric speciation and isolating behaviour have produced today's diversity of mallard-like ducks despite the fact that, in most, if not all, of these populations, hybridisation must have occurred to some extent.[122]

Invasiveness

Mallards are causing severe "genetic pollution" to South Africa's biodiversity by breeding with endemic ducks[123] even though the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds – an agreement to protect the local waterfowl populations – applies to the mallard as well as other ducks.[124] The hybrids of mallards and the yellow-billed duck are fertile, capable of producing hybrid offspring.[125] If this continues, only hybrids occur and in the long term result in the extinction of various indigenous waterfowl.[125] The mallard can crossbreed with 63 other species, posing a severe threat to indigenous waterfowl's genetic integrity.[126] Mallards and their hybrids compete with indigenous birds for resources, including nest sites, roosting sites, and food.[123]

Availability of mallards, mallard ducklings, and fertilised mallard eggs for public sale and private ownership, either as poultry or as pets, is currently legal in the United States, except for the state of Florida, which has currently banned domestic ownership of mallards. This is to prevent hybridisation with the native mottled duck.[127]

The mallard is considered an invasive species in Australia and New Zealand,[22]: 505 where it competes with the Pacific black duck (known as the grey duck locally in New Zealand) which was over-hunted in the past. There, and elsewhere, mallards are spreading with increasing urbanisation and hybridising with local relatives.[113]

The eastern or Chinese spot-billed duck is currently introgressing into the mallard populations of the Primorsky Krai, possibly due to habitat changes from global warming.[19] The Mariana mallard was a resident allopatric population – in most respects a good species – apparently initially derived from mallard-Pacific black duck hybrids;[128] unfortunately, it became extinct in the late 20th century.[129]

The Laysan duck is an insular relative of the mallard, with a very small and fluctuating population.[130][1] Mallards sometimes arrive on its island home during migration, and can be expected to occasionally have remained and hybridised with Laysan ducks as long as these species have existed.[131] However, these hybrids are less well adapted to the peculiar ecological conditions of Laysan Island than the local ducks, and thus have lower fitness. Laysan ducks were found throughout the Hawaiian archipelago before 400 AD, after which they suffered a rapid decline during the Polynesian colonisation.[132] Now, their range includes only Laysan Island.[132] It is one of the successfully translocated birds, after having become nearly extinct in the early 20th century.[133]

Relationship with humans

Domestication

Mallards have often been ubiquitous in their regions among the ponds, rivers, and streams of human parks, farms, and other human-made waterways – even to the point of visiting water features in human courtyards.[134]

Mallards have had a long relationship with humans. Almost all domestic duck breeds derive from the mallard, with the exception of a few Muscovy breeds,[135] and are listed under the trinomial name A. p. domesticus. Mallards are generally monogamous while domestic ducks are mostly polygamous. Domestic ducks have no territorial behaviour and are less aggressive than mallards.[136] Domestic ducks are mostly kept for meat; their eggs are also eaten, and have a strong flavour.[136] They were first domesticated in Southeast Asia at least 4,000 years ago, during the Neolithic Age, and were also farmed by the Romans in Europe, and the Malays in Asia.[137] As the domestic duck and the mallard are the same species as each other, it is common for mallards to mate with domestic ducks and produce hybrid offspring that are fully fertile.[138] Because of this, mallards have been found to be contaminated with the genes of the domestic duck.[138]

While the keeping of domestic breeds is more popular, pure-bred mallards are sometimes kept for eggs and meat,[139] although they may require wing clipping to restrict flying, or training to navigate and fly home.[140]

Hunting

Mallards are one of the most common varieties of ducks hunted as a sport due to the large population size. The ideal location for hunting mallards is considered to be where the water level is somewhat shallow where the birds can be found foraging for food.[141] Hunting mallards might cause the population to decline in some places, at some times, and with some populations.[142] In certain countries, the mallard may be legally shot but is protected under national acts and policies. For example, in the United Kingdom, the mallard is protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, which restricts certain hunting methods or taking or killing mallards.[143]

As food

Since ancient times, the mallard has been eaten as food. The wild mallard was eaten in Neolithic Greece.[144] Usually, only the breast and thigh meat is eaten.[145] It does not need to be hung before preparation, and is often braised or roasted, sometimes flavoured with bitter orange or with port.[146]

References

- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2019) [amended version of 2017 assessment]. "Anas platyrhynchos". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T22680186A155457360. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22680186A155457360.en. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Laurentius Salvius. p. 125.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781408133262.

- ^ Johnsgard, Paul A. (1961). "Anas_boschas_platyrhynchos_Linnaeus" "Evolutionary relationships among the North American mallards". The Auk. 78 (1): 3–43 [11–12]. doi:10.2307/4082232. JSTOR 4082232.

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm. pp. 46, 309. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Burt, D.W.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, Wubin; Kim, Heebal; Gan, Shangquan; Zhao, Yiqiang; Li, Jianwen; Yi, Kang; Feng, Huapeng; Zhu, Pengyang; Li, Bo; Liu, Qiuyue; Fairley, Suan; Magor, Katharine E; Du, Zhenlin; Hu, Xiaoxiang; Goodman, Laurie; Tafer, Hakim; Vignal, Alain; Lee, Taeheon; Kim, Kyu-Won; Sheng, Zheya; An, Yang; Searle, Steve; Herrero, Javier; Groenen, Martien A.M.; et al. (2013). "The duck genome and transcriptome provide insight into an avian influenza virus reservoir species". Nature Genetics. 45 (7): 776–783. doi:10.1038/ng.2657. PMC 4003391. PMID 23749191.

- ^ Magnus, PD (2012), Scientific Enquiry and Natural Kinds: from Planets to Mallards, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 9781137271259

- ^ Buckingham, James Silk; Sterling, John; Maurice, Frederick Denison; Stebbing, Henry; Dilke, Charles Wentworth; Hervey, Thomas Kibble; Dixon, William Hepworth; Maccoll, Norman; Rendall, Vernon Horace (1904). The Athenaeum: A Journal of Literature, Science, the Fine Arts, Music, and the Drama. J. Francis.

- ^ "mallard". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 1989.

- ^ Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1862). Dictionary of English Etymology. Trübner and Company.

- ^ Phillips, John C. (1915). "Experimental studies of hybridization among ducks and pheasants". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 18 (1): 69–112. doi:10.1002/jez.1400180103.

- ^ a b Steadman, David W. (2005). "Late Pleistocene Birds from Kingston Saltpeter Cave, Southern Appalachian Mountains, Georgia". The Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History: 231–248.

- ^ Anonymous (1937). Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Oliver & Boyd. p. 210.

- ^ Johnson, Kevin P.; Sorenson, M.D. (1999). "Phylogeny and biogeography of dabbling ducks (genus Anas): a comparison of molecular and morphological evidence" (PDF). The Auk. 116 (3): 792–805. doi:10.2307/4089339. JSTOR 4089339.

- ^ a b Kulikova, Irina V.; Drovetski, S.V.; Gibson, D.D.; Harrigan, R.J.; Rohwer, S.; Sorenson, Michael D.; Winker, K.; Zhuravlev, Yury N.; McCracken, Kevin G. (2005). "Phylogeography of the Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos): hybridization, dispersal, and lineage sorting contribute to complex geographic structure". The Auk. 122 (3): 949–965. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2005)122[0949:POTMAP]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 85668932. (Erratum: The Auk 122 (4): 1309, doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2005)122[1309:POTMAP2.0.CO;2].)

- ^ Delacour, Jean (1964). The Waterfowl of the World. Country Life.

- ^ Kraus, R.H.S.; Zeddeman, A.; van Hooft, P.; Sartakov, D.; Soloviev, S.A.; Ydenberg, Ronald C.; Prins, Herbert H.T. (2011). "Evolution and connectivity in the world-wide migration system of the mallard: Inferences from mitochondrial DNA". BMC Genetics. 12 (99): 99. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-12-99. PMC 3258206. PMID 22093799.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Kraus, R.H.S.; van Hooft, P.; Megens, H.-J.; Tsvey, A.; Fokin, S.Y.; Ydenberg, Ronald C.; Prins, Herbert H.T. (2013). "Global lack of flyway structure in a cosmopolitan bird revealed by a genome wide survey of single nucleotide polymorphisms". Molecular Ecology. 22 (1) (published January 2013): 41–55. doi:10.1111/mec.12098. PMID 23110616. S2CID 11190535.

- ^ a b Kulikova, Irina V.; Zhuravlev, Yury N.; McCracken, Kevin G. (2004). "Asymmetric hybridization and sex-biased gene flow between Eastern Spot-billed Ducks (Anas zonorhyncha) and Mallards (A. platyrhynchos) in the Russian Far East". The Auk. 121 (3): 930–949. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2004)121[0930:AHASGF]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 17470882.

- ^ Lavretsky, Philip; McCracken, Kevin G.; Peters, Jeffrey L. (January 2014). "Phylogenetics of a recent radiation in the mallards and allies (Aves: Anas): inferences from a genomic transect and the multispecies coalescent". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 70: 402–411. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2013.08.008. ISSN 1095-9513. PMID 23994490.

- ^ a b c Ogilvie, M. A.; Young, Steve (2002). Wildfowl of the World. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 9781843303282.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cramp, Stanley, ed. (1977). Handbook of the Birds of Europe the Middle East and North Africa, the Birds of the Western Palearctic. Vol. 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198573586.

- ^ Dunning, John B. Jr., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ Madge, Steve (1992). Waterfowl: An Identification Guide to the Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-395-46726-8.

- ^ Ogilvie, M. A.; Young, Steve (2002). Wildfowl of the World. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 9781843303282.

- ^ Jiguet, Frédéric; Audevard, Aurélien (21 March 2017). Birds of Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East: A Photographic Guide. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691172439.

- ^ a b Fergus, Charles; Hansen, Amelia (2000). Wildlife of Pennsylvania and the Northeast. Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811728997.

- ^ a b Lancaster, Frank Maurice (17 December 2013). The inheritance of plumage colour in the common duck (Anas platyrhynchos linné). Springer. ISBN 9789401768344.

- ^ Station, Delta Waterfowl and Wetlands Research (1984). Annual Report. The Station.

- ^ a b c Moulton, Judy (7 November 2014). Daisy and Ducky Mallard. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 9781503511910.[self-published source]

- ^ a b Vinicombe, Keith (27 March 2014). The Helm Guide to Bird Identification. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781472905543.

- ^ Robinson, R.A. (2005). "Mallard Anas platyrhynchos". BirdFacts: profiles of birds occurring in Britain & Ireland (BTO Research Report 407). British Trust for Ornithology. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ Moss, Stephen; Cottridge, David (2000). Attracting Birds to Your Garden. New Holland Publishers. ISBN 9781859740057.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Kenn (2005). Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0618574230.

- ^ "Everglades News | Mallards". American Bird. 3 June 2015. Archived from the original on 7 September 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ a b Hicks, James Stephen (1923). The Encyclopaedia of Poultry. Waverley Book Company.

- ^ "Ducks 'quack in regional accents'". 4 June 2004. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Ducks quack in cockney, study finds". www.abc.net.au. 4 June 2004. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ Dyer, Antoinette B.; Gottlieb, Gilbert (1990). "Auditory basis of maternal attachment in ducklings (Anas platyrhynchos) under simulated naturalistic imprinting conditions". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 104 (2): 190–194. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.104.2.190. ISSN 1939-2087. PMID 2364664.

- ^ Bent, Arthur Cleveland (1962). Life Histories of North American Wild Fowl. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486254227.

- ^ Salewski, Volker; Hochachka, Wesley M.; Fiedler, Wolfgang (September 2009). "Global warming and Bergmann's rule: do central European passerines adjust their body size to rising temperatures?". Oecologia. 162 (1): 247–260. doi:10.1007/s00442-009-1446-2. ISSN 0029-8549. PMC 2776161. PMID 19722109.

- ^ Shelomi, Matan; Zeuss, Dirk (2017). "Bergmann's and Allen's Rules in Native European and Mediterranean Phasmatodea". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 5. doi:10.3389/fevo.2017.00025. ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ Bidau, Claudio J.; Martí, Dardo A. (August 2008). "A test of Allen's rule in ectotherms: the case of two south American Melanopline Grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acrididae) with partially overlapping geographic ranges". Neotropical Entomology. 37 (4): 370–380. doi:10.1590/S1519-566X2008000400004. ISSN 1519-566X. PMID 18813738.

- ^ Ducks Unlimited Magazine. Vol. 67–68. Ducks Unlimited, Incorporated. 2003. p. 62.

- ^ "Brewer's Duck". audubon.org. National Audubon Society. Archived from the original on 13 May 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ a b Madge, Steve (2010). Wildfowl. A&C Black. p. 212. ISBN 9781408138953.

- ^ Skerrett, Adrian; Disley, Tony (2016). Birds of Seychelles. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 9781472946010.

- ^ a b c d Finlayson, Clive (2010). Birds of the Strait of Gibraltar. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 219. ISBN 9781408136942.

- ^ Prins, Herbert H. T.; Namgail, Tsewang (6 April 2017). Bird Migration across the Himalayas: Wetland Functioning amidst Mountains and Glaciers. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107114715.

- ^ a b Yamaguchi, Noriyuki; Hiraoka, Emiko; Fujita, Masaki; Hijikata, Naoya; Ueta, Mutsuyuki; Takagi, Kentaro; Konno, Satoshi; Okuyama, Miwa; Watanabe, Yuki (September 2008). "Spring migration routes of mallards (Anas platyrhynchos) that winter in Japan, determined from satellite telemetry". Zoological Science. 25 (9): 875–881. doi:10.2108/zsj.25.875. ISSN 0289-0003. PMID 19267595. S2CID 23445791.

- ^ Lever, Christopher (2010). Naturalised Birds of the World. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 9781408133125.

- ^ Lever, Christopher (2010). Naturalised Birds of the World. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 9781408133125.

- ^ Anonymous. International Wildfowl Inquiry Volume i Factors Affecting the General Status of Wild Geese and Wild Duck. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Smith, Loren M.; Pederson, Roger L.; Kaminski, Richard M. (1989). Habitat Management for Migrating and Wintering Waterfowl in North America. Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 9780896722040.

- ^ Service, U. S. Fish and Wildlife (1975). Final environmental statement for the issuance of annual regulations permitting the sport hunting of migratory birds. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

- ^ Tunnell, John Wesley; Judd, Frank W. (2002). The Laguna Madre of Texas and Tamaulipas. Texas A&M University Press. p. 180. ISBN 9781585441334.

- ^ Winkler, Lawrence (2012). Westwood Lake Chronicles. Lawrence Winkler. ISBN 9780991694105.

- ^ Mulligan, Jesse (6 September 2018). "The loneliest duck in Niue". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Lyons, Kate (7 September 2018). "Trevor the lonely duck gets tiny island of Niue in a flap". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ Guthrie, Russell Dale (2001). People and Wildlife in Northern North America: Essays in Honor of R. Dale Guthrie. Archaeopress. ISBN 9781841712369.

- ^ Burton, Maurice; Burton, Robert (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia: Leopard – marten. Marshall Cavendish. p. 1525. ISBN 9780761472773.

- ^ "Mallard Duck • Elmwood Park Zoo | Elmwood Park Zoo | www.elmwoodparkzoo.org". www.elmwoodparkzoo.org. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Abraham, Richard L. (1 October 1974). "Vocalizations of the Mallard (Anas Platyrhynchos)" (PDF). The Condor: Ornithological Applications. 76 (4): 401–420. doi:10.2307/1365814. JSTOR 1365814. S2CID 2319728. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- ^ van Toor, Mariëlle L.; Hedenström, Anders; Waldenström, Jonas; Fiedler, Wolfgang; Holland, Richard A.; Thorup, Kasper; Wikelski, Martin (30 August 2013). "Flexibility of Continental Navigation and Migration in European Mallards". PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e72629. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...872629V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0072629. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3758317. PMID 24023629.

- ^ Krapu, Gary L.; Reinecke, Kenneth J. (1992). "Foraging ecology and nutrition". In Batt, Bruce D.J.; Afton, Alan D.; Anderson, Michael G.; Ankney, C. Davison; Johnson, Douglas H.; Kadlec, John A.; Krapu, Gary L. (eds.). Ecology and Management of Breeding Waterfowl. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 1–30 (10). ISBN 978-0-8166-2001-2.

- ^ a b c Baldassarre, Guy A. (2014). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of North America. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 410. ISBN 9781421407517.

- ^ Eldridge, Jan (1990). "Waterfowl Management Handbook" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Leaflet.

- ^ a b Rappole, John H. (2012). Wildlife of the Mid-Atlantic: A Complete Reference Manual. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0812222012.

- ^ Swanson, George A.; Meyer, Mavis I.; Adomaitis, Vyto A. (1985). "Foods consumed by breeding mallards on wetlands of south-central North Dakota". Journal of Wildlife Management. 49 (1): 197–203. doi:10.2307/3801871. JSTOR 3801871.

- ^ Gruenhagen, Ned M.; Fredrickson, Leigh H. (1990). "Food use by migratory female mallards in northwest Missouri". Journal of Wildlife Management. 54 (4): 622–626. doi:10.2307/3809359. JSTOR 3809359.

- ^ Combs, Daniel L.; Fredrickson, Leigh H. (1990). "Foods used by male mallards wintering in southeastern Missouri". Journal of Wildlife Management. 60 (3): 603–610. doi:10.2307/3802078. JSTOR 3802078.

- ^ Sandilands, Al (2011). Birds of Ontario: Habitat Requirements, Limiting Factors, and Status: Volume 1–Nonpasserines: Loons through Cranes. University of British Columbia Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780774859431.

- ^ Briggs, Helen (30 June 2017). "Wild ducks caught on camera snacking on small birds". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ^ Lipton, James (1991). An Exaltation of Larks. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-30044-0.

- ^ Anonymous (2005). The Encyclopedia of Birds. Parragon Publishing India. p. 50. ISBN 9781405498517.

- ^ Ginn, H. B.; Melville, Dorothy Sutherland (1983). Moult in birds. British Trust for Ornithology. ISBN 9780903793025.

- ^ Boere, G. C.; Galbraith, Colin A.; Stroud, David A. (2006). Waterbirds Around the World: A Global Overview of the Conservation, Management and Research of the World's Waterbird Flyways. The Stationery Office. ISBN 9780114973339.

- ^ a b Boere, G. C.; Galbraith, Colin A.; Stroud, David A. (2006). Waterbirds Around the World: A Global Overview of the Conservation, Management and Research of the World's Waterbird Flyways. The Stationery Office. p. 359. ISBN 9780114973339.

- ^ Feinstein, Julie (2011). Field Guide to Urban Wildlife. Stackpole Books. p. 130. ISBN 9780811705851.

- ^ "The secret life of mallard ducks". Scottish Wildlife Trust. 29 March 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Nesting mallards". The RSPB. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ a b Burton, Maurice; Burton, Robert (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia: Leopard – marten. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761472773. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Hauber, Mark E. (2014). The Book of Eggs: A Life-Size Guide to the Eggs of Six Hundred of the World's Bird Species. University of Chicago Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-226-05781-1.

- ^ DK; International, BirdLife (1 March 2011). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Birds. Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 9781405336161.

- ^ "Urban Mallards - Portland Audubon". Audubonportland.org. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Townsley, Frank (10 March 2016). British Columbia: Graced by Nature's Palette. FriesenPress. ISBN 9781460277737.

- ^ "Mallard Ducklings | Nesting Ducks". The RSPB. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Sheppard, J.L.; Amundson, C.L.; Arnold, T.W.; Klee, D. (2019). "Nesting ecology of a naturalized population of Mallards Anas platyrhynchos in New Zealand". Ibis. 161 (3): 504–520. doi:10.1111/ibi.12656. S2CID 91988206.

- ^ "Ducklings hatch at London Wetland Centre". BBC News. 20 November 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Kear, Janet (30 November 2010). Man and Wildfowl. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781408137604.

- ^ Cunningham, Emma J. A. (1 May 2003). "Female mate preferences and subsequent resistance to copulation in the mallard". Behavioral Ecology. 14 (3): 326–333. doi:10.1093/beheco/14.3.326. ISSN 1045-2249.

- ^ "Duck Displays". web.stanford.edu. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d Moeliker, Cornelis (2001). "The first case of homosexual necrophilia in the mallard Anas platyrhynchos (Aves:Anatidae)" (PDF). Deinsea 8: 243–248.

- ^ Annals of Improbable Research. MIT Museum. 2005.

- ^ Baldassarre, Guy A. (2014). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of North America. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421407517.

- ^ a b Drilling, Nancy; Titman, Roger; McKinney, Frank (2002). Poole, A. (ed.). "Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos)". The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.658. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ^ Martz, Gerald F. (1967). "Effects of nesting cover removal on breeding puddle ducks". Journal of Wildlife Management. 31 (2): 236–247. doi:10.2307/3798312. JSTOR 3798312.

- ^ "Impact of Red Fox Predation on the Sex Ratio of Prairie Mallards". USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 3 August 2006. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ Marquiss, M.; Leitch, A. F. (1 October 1990). "The diet of Grey Herons Ardea cinerea breeding at Loch Leven, Scotland, and the importance of their predation on ducklings". Ibis. 132 (4): 535–549. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1990.tb00277.x. ISSN 1474-919X.

- ^ Reader's Digest Scenic wonders of Canada: an illustrated guide to our natural splendors. Reader's Digest Association (Canada). 1976. ISBN 9780888500496.

- ^ Adams, Mary (October 1995). Ecosystem Matters: Activity and Resource Guide for Environmental Educators. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 9780788124532.

- ^ Fray, Rob; Davies, Roger; Gamble, Dave; Harrop, Andrew; Lister, Steve (30 June 2010). The Birds of Leicestershire and Rutland. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781408133118.

- ^ Sperry, Mark L. "Common Loon Attacks on Waterfowl" (PDF). Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Wetland Wildlife Populations and Research Group.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "A Mallard Duckling Is Thriving—and Maybe Diving—Under the Care of Loon Parents". Audubon. 12 July 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Niels C., Rattenborg (1999). "Half-awake to the risk of predation". Nature. 397 (6718): 397–398. Bibcode:1999Natur.397..397R. doi:10.1038/17037. PMID 29667967. S2CID 4427166.

- ^ "IUCN Red List maps".

- ^ "Anas platyrhynchos (Common Mallard, Mallard, Northern Mallard)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ^ a b Mooney, H. A.; Cleland, E. E. (8 May 2001). "The evolutionary impact of invasive species". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (10): 5446–5451. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.5446M. doi:10.1073/pnas.091093398. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 33232. PMID 11344292.

- ^ Leedy, Daniel L.; Adams, Lowell W. (1984). A Guide to Urban Wildlife Management. National Institute for Urban Wildlife.

- ^ a b c Uyehara, Kimberly; Engilis, Andrew; Reynolds, Michelle. Hendley, James (ed.). "Hawaiian Duck's Future Threatened by Feral Mallards" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "Of a Feather: Why this duck?". The Eagle Times.

- ^ a b Rhymer, Judith M. (2006). "Extinction by hybridization and introgression in anatine ducks" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Sinica. 52 (Supplement): 583–585.

- ^ a b c d e Rhymer, Judith M.; Simberloff, Daniel (1996). "Extinction by hybridization and introgression". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 27: 83–109. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.83.

- ^ Griffin, C.R.; Shallenberger, F.J.; Fefer, S.I. (1989). "Hawaii's endangered waterbirds: a resource management challenge". In Sharitz, R.R.; Gibbons, I.W. (eds.). Proceedings of Freshwater Wetlands and Wildlife Symposium. Savannah River Ecology Lab. pp. 155–169.

- ^ a b Williams, Murray; Basse, Britta (2006). "Indigenous gray ducks, Anas superciliosa, and introduced mallards, A. platyrhynchos, in New Zealand: processes and outcome of a deliberate encounter" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Sinica. 52 (Supplement): 579–582.

- ^ Avise, John C.; Ankney, C. Davison; Nelson, William S. (1990). "Mitochondrial gene trees and the evolutionary relationship of Mallard and Black Ducks" (PDF). Evolution. 44 (4): 1109–1119. doi:10.2307/2409570. JSTOR 2409570. PMID 28569026.

- ^ Mank, Judith E.; Carlson, John E.; Brittingham, Margaret C. (2004). "A century of hybridization: decreasing genetic distance between American black ducks and mallards". Conservation Genetics. 5 (3): 395–403. doi:10.1023/B:COGE.0000031139.55389.b1. S2CID 24144598.

- ^ a b McCracken, Kevin G.; Johnson, William P.; Sheldon, Frederick H. (2001). "Molecular population genetics, phylogeography, and conservation biology of the mottled duck (Anas fulvigula)". Conservation Genetics. 2 (2): 87–102. doi:10.1023/A:1011858312115. S2CID 17895466.

- ^ Young, H. Glyn; Rhymer, Judith M. (1998). "Meller's duck: A threatened species receives recognition at last". Biodiversity and Conservation. 7 (10): 1313–1323. doi:10.1023/A:1008843815676. S2CID 27384967.

- ^ American Ornithologists' Union (1983). Check-list of North American Birds (6th ed.). American Ornithologists' Union.

- ^ Kirby, Ronald E.; Sargeant, Glen A.; Shutler, Dave (2004). "Haldane's rule and American black duck × mallard hybridization". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 82 (11): 1827–1831. doi:10.1139/z04-169.

- ^ Tubaro, Pablo L.; Lijtmaer, Dario A. (1 October 2002). "Hybridization patterns and the evolution of reproductive isolation in ducks". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 77 (2): 193–200. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8312.2002.00096.x. ISSN 0024-4066.

- ^ a b "Invasive Alien Bird Species Pose A Threat, Kruger National Park, Siyabona Africa Travel (Pty) Ltd – South Africa Safari Travel Specialist". krugerpark.co.za. 2008. Archived from the original on 12 November 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ "Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds" (PDF). Official Journal of the European Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Marina da Gama". www.mdga.co.za. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ Marsh, David (1 June 2010). "Those mighty mallards can bust the speed limit". San Quentin News. Archived from the original on 15 June 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "Mallard Possession Rule". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 10 July 2004. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ Yamashina, Y. (1948). "Notes on the Marianas mallard". Pacific Science. 2: 121–124.

- ^ Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (2010) [1989]. Wildfowl. Christopher Helm Publications. p. 211. ISBN 978-1408138953.

- ^ Browne, Robert; Griffin, Curtice; Chang, Paul; Hubley, Mark; Martin, Amy (1993). "Genetic Divergence Among Populations of the Hawaiian Duck, Laysan Duck, and Mallard". The Auk. 110 (1): 49–56. JSTOR 4088230.

- ^ "Recovery Strategy – Laysan Duck Revised Recovery Plan". www.fws.gov. September 2009. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ a b Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C. S.; Jones, T.; Hammond, G. S.; Dewey, T. A. (2016). "Anas laysanensis (Laysan duck)". Animal Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ^ "Clostridium Infections". Advances in Research and Treatment (2011 ed.). ScholarlyEditions. 9 January 2012. ISBN 9781464960130.

- ^ Channel Improvements, Columbia and Lower Willamette River Federal Navigation Channel, (OR, WA): Environmental Impact Statement. 1999.

- ^ Appleby, Michael C.; Mench, Joy A.; Hughes, Barry O. (2004). Poultry Behaviour and Welfare. CABI. ISBN 9780851996677.

- ^ a b Piggott, Stuart; Thirsk, Joan (2 April 1981). The Agrarian History of England and Wales: Volume 1, Part 1, Prehistory. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521087414.

- ^ Kear, Janet (2005). Ducks, Geese and Swans: General chapters, species accounts (Anhima to Salvadorina). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-61008-3.

- ^ a b Wood-Gush, D. (6 December 2012). Elements of Ethology: A textbook for agricultural and veterinary students. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9789400959316.

- ^ "Raising Mallard Ducks: How to Raise Mallards In Your Backyard Duck Yard – DuckHobby.com". Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Flying ducks". BackYard Chickens. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ O'Neill, Michael J. (February 1973). Field & Stream. Vol. 77. Columbia Broadcasting System Publications. p. 108.

- ^ Cape Cod National Seashore (N.S.), Hunting Program: Environmental Impact Statement. 2007. p. 90.

- ^ Walsingham, Lord (2016). Tips for Pheasant Shooting from some of the Finest Hunters. Read Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1473357051.

- ^ Dalby, Andrew (15 April 2013). Food in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. ISBN 9781135954222.

- ^ The Visual Food Encyclopedia. Québec Amerique. 1996. ISBN 9782764408988.

- ^ Davidson, Alan (2006). The Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford University Press. p. 472. ISBN 9780191018251.

External links

- "Mallard media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Mallard photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)