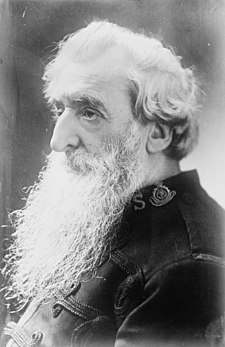

William Booth

William Booth | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st General of The Salvation Army | |

| In office 2 July 1865 – 20 August 1912 | |

| Chief | Bramwell Booth |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Bramwell Booth |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 April 1829 Sneinton, Nottingham, England |

| Died | 20 August 1912 (aged 83) Hadley Wood, London, England |

| Spouse | Catherine Mumford |

| Children | |

| Signature |  |

William Booth (10 April 1829 – 20 August 1912) was an English Methodist preacher who, along with his wife, Catherine, founded the Salvation Army and became its first General (1878–1912). The Christian movement with a quasi-military structure and government founded in 1865 has spread from London to many parts of the world. It is known for being one of the largest distributors of humanitarian aid.

Early life

[edit]William Booth was born in Sneinton, Nottingham, the second son of five children born to Samuel Booth and his second wife, Mary Moss.[1] His birthplace is now a museum.[2] Booth's father was a nailmaker and builder from Belper in Derbyshire but, during William's childhood, the family descended into poverty. In 1842, Samuel Booth, who could no longer afford his son's school fees, apprenticed the 13-year-old William to a pawnbroker. Samuel Booth died on 23 September 1842.[3]

Two years into his apprenticeship Booth had a religious conversion.[4] He then read extensively and trained himself in writing and in speech, becoming a Methodist local preacher. Booth was encouraged to be an evangelist primarily through his best friend, Will Sansom. Both Sansom and Booth began in the 1840s to preach to the poor and the sinners of Nottingham, and Booth would probably have remained as Sansom's partner in his new Mission ministry, as Sansom titled it, if Sansom had not died of tuberculosis, in 1849.[5]

When his apprenticeship ended in 1848, Booth was unemployed and spent a year looking in vain for work.[6] In 1849, Booth reluctantly left his family and moved to London, where he found work with a pawnbroker. Booth tried to continue lay preaching in London, but the small amount of preaching work that came his way frustrated him, and so he resigned as a lay preacher and took to open-air evangelising in the streets and on Kennington Common.

Methodist ministry

[edit]

In 1851, Booth joined the Methodist Reform Church, formed in 1849 by a breakaway from the Wesleyan Methodist Church. On 10 April 1852, his 23rd birthday, he left pawnbroking and became a full-time preacher at their headquarters at Binfield Chapel in Clapham. William styled his preaching after the revivalist American James Caughey, who had made frequent visits to England and preached at Broad Street Chapel, Nottingham, where Booth was a member. Just over a month after he started full-time preaching, on 15 May 1852, William Booth became formally engaged to Catherine Mumford.

Interested in the Congregationalist approach, Booth consulted David Thomas at Stockwell about the ministry. Through Thomas, he met John Campbell and then James William Massie. The recommendation was training under Rev. John Frost; but Booth disliked Frost's school, and soon left.[7] In November 1853, he was invited to become the Reformers' minister at Spalding in Lincolnshire. He married Catherine Mumford on 17 June 1855 at Stockwell Green Congregational Church in London.

In the summer of 1857 the Booth family moved to Brighouse in the West Riding of Yorkshire, where he was appointed preacher at the Bethel Chapel. William and Catherine campaigned against the employment of seven-year-old girls in a local mill. On the former chapel in Bethel Street, which is now a Wetherspoons pub, there is a blue plaque commemorating that Booth served there.[8] By 1859 he and his wife had moved to Gateshead.

Though Booth was now a prominent Methodist evangelist, he was unhappy that the annual conference of the denomination kept assigning him to a pastorate, the duties of which he had to neglect to respond to the frequent requests that he do evangelistic campaigns. At the Liverpool conference in 1861, after having spent three years at Gateshead, his request to be freed for evangelism full-time was refused yet again, and Booth resigned from the ministry of the Methodist New Connexion.[9]

Soon he was barred from campaigning in Methodist congregations, so he became an independent evangelist. His doctrine remained much the same, though; he preached that eternal punishment was the fate of those who do not believe the Gospel of Jesus Christ and the necessity of repentance from sin, and the promise of holiness. He taught that this belief would manifest itself in a life of love for God and mankind.[citation needed] The Ethical characteristic of Booth's business ventures was evident in the manufacture of boxes of Salvation Army matches[10] which bore the slogan "Lights in darkest England, Security from fire, Fair wages for fair work". His match factory on Old Ford paid 4 pence a gross, while the larger firms only paid 2 1/2 pence.

The Christian Mission

[edit]

The tent was set up on an old Quaker burial ground on Mile End Waste in Whitechapel, with an initial goal to deliver the Good News to all.[11]

By 1865, Booth and his wife had opened 'The Christian Revival Society' in the East End of London, which held regular evening meetings to share the repentance that Booth believed Christian salvation could bring both the poor and marginalised. The Christian Revival Society was renamed The Christian Mission, subsequently to become the East London Christian Mission.[12] The Christian Mission's slow growth was hard work for Booth; his wife writes that he would "stumble home night after night haggard with fatigue, often his clothes were torn and bloody bandages swathed his head where a stone had struck".[13]

Evening meetings were held in an old warehouse where urchins threw stones and fireworks through the window.[citation needed] Outposts were established throughout the city, attracting converts, but the Christian Mission remained just one of the five hundred charitable groups working in London's East End.[11]

Booth practised various types of charity himself, such as opening "Food for the Million" (soup kitchens).[citation needed]

The Salvation Army

[edit]

Having been founded as the East London Christian Mission in 1865, the name The Salvation Army developed from an incident in May 1878. William Booth was dictating a letter to his secretary George Scott Railton and said, "We are a volunteer army." Bramwell Booth heard his father and said, "Volunteer, I'm no volunteer, I'm a regular!" Railton was instructed to cross out the word "volunteer" and substitute the word "salvation".[14](The printer's proof copy of the Missions' report for 1878 declared "The Christian Mission Is A Volunteer Army", but the corrected proof read "The Christian Mission Is ... A Salvation Army"[15]) The Salvation Army was modelled after the military, with its own flag (or colours) and its own music, often with Christian words to popular and folkloric tunes sung in the pubs. Booth and the other soldiers in "God's Army" would wear the army's own uniform, 'putting on the armour,' for meetings and ministry work. He became the "General" and his other ministers were given appropriate ranks as "officers". Other members became "soldiers".

Though the early years were lean ones, with the need of money to help the needy an ever growing issue, Booth and The Salvation Army persevered. In the early 1880s, operations were extended to other countries, notably the United States, France, Switzerland, Sweden and others, including to most of the countries of the British Empire: Australia, Canada, India, Cape Colony, New Zealand, Jamaica, etc.

Often the beginnings in other countries occurred through "salvationist" activities by non-officers who had emigrated. With some initial success they would contact London to 'send officers.'

In other cases, like in Argentina, a non-salvationist told Booth that there were thousands of British people there who needed salvation. The four officers sent in 1890 found that those British were scattered all over the pampas. But the missionaries started ministry in the Spanish language and the work spread throughout the country – initially following the rail-road development, since the British in charge of building the rail-roads were usually sympathetic to the movement.

During his lifetime, William Booth established Army work in 58 countries and colonies, travelling extensively and holding, "salvation meetings."

Booth regularly published a magazine and was the author of a number of books; he also composed several songs. His book In Darkest England and the Way Out not only became a best-seller after its 1890 release, it set the foundation for the army's modern social welfare approach. It compared what was considered "civilised" England with "Darkest Africa" – a land then considered poor and backward. What Booth suggested was that much of London and greater England after the Industrial Revolution was not better off in the quality of life than those in the underdeveloped world. He proposed a strategy to apply the Christian Gospel and work ethic to the problems. The book speaks of abolishing vice and poverty by establishing homes for the homeless, farm communities such as Hadleigh Farm where the urban poor can be trained in agriculture, training centres for prospective emigrants, homes for fallen women and released prisoners, aid for the poor, and help for drunkards. He also lays down schemes for poor men's lawyers, banks, clinics, industrial schools and even a seaside resort.

Opposition

[edit]

During its early years The Salvation Army faced opposition, especially from those in the alcohol-selling industry who were concerned that the activities of Booth and his followers would persuade the poorer classes to stop drinking. One group opposed to Booth and The Salvation Army was the Skeleton Army, a diffuse group, particularly in Southern England, that opposed and disrupted The Salvation Army's marches against alcohol from the early 1880s until about 1892. Clashes between the two groups led to the deaths of several Salvationists and injuries to many others. During 1882 alone, 662 Salvation Army soldiers were assaulted: 251 of them were women and 23 of them were under fifteen years of age.[16]

Other accusations centred around the fact that Booth appointed his own children to posts for which others were better qualified, leading to claims that The Salvation Army was a Booth family business. For example, he appointed his daughter Emma Booth as the Principal of the Officers' Training Home, The Salvation Army's first training school for women when she was just 19. While William Booth had once said to his children that "The Salvation Army does not belong to you, or to me, it belongs to the world" and was very wary of the leadership of the army becoming a dynasty,[17] others believed that Booth was creating a dynasty, as was suggested by the fact that he insisted that his sons-in-law added 'Booth' to their own names (see Frederick Booth-Tucker and Arthur Booth-Clibborn).[18] This was further borne out when Booth appointed his son, Bramwell Booth, as his successor as General in his will.

The press was often hostile to Booth and The Salvation Army as well because their methods and message were widely misinterpreted. The army's motto "Blood & Fire", which had theological meaning representing the saving "blood of Jesus" and the sanctifying "fire of the Holy Spirit", was erroneously thought to mean the blood of sinners and the fire of hell. There was also suspicion about the army's motives, with Booth often portrayed as a charlatan only out to make money.[19]

The Church of England was at first hostile to the activities of Booth and The Salvation Army. The philanthropist, politician, and evangelist Lord Shaftesbury even went so far as to describe Booth as the "Anti-Christ". One of the main complaints against Booth was his "elevation of women to man's status". Many found him dictatorial and hard to work with. Some of his own children denounced him as their leader and turned their backs on The Salvation Army, including his daughter Kate Booth and his sons Herbert and Ballington Booth, the latter founding a separate organisation, the Volunteers of America with himself as "General". The evangelist Rodney "Gipsy" Smith left him because of his rigidity and Dwight L. Moody would not support him because he felt there was a threat to the local church.[20]

Later years

[edit]

Opinion of The Salvation Army and William Booth eventually changed to that of favour. In his later years, he was received in audience by kings, emperors and presidents. The mass media began to use his title of 'General' with reverence.

In 1899, Booth suffered from blindness in both eyes, but with a short rest, was able to recover his sight. In 1904 he took part in a motor tour when he was driven around Great Britain, stopping off in cities, towns and villages to preach to the crowds from his open-top car. In 1906 Booth was made a Freeman of the City of London, and was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Oxford. In 1902 he was invited to attend the coronation of Edward VII and Alexandra.

He made his last visit to North America in 1907, and in 1909 he embarked on a six-month motor tour of the United Kingdom. During this tour he discovered he was blind in his right eye and the sight in his left eye was dimmed by cataracts. The rest of the tour had to be cancelled. On 21 August 1909 a surgeon at Guy's Hospital removed his right eye. Despite this setback, in 1910 Booth campaigned in the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, Switzerland and Italy. On his return to England, he embarked on his seventh and last motor tour.

William Booth died at age 83 on 20 August 1912 (or, in Salvationist parlance, was Promoted to Glory) at his home in Hadley Wood, London. His body lay in state for three days at Clapton Congress Hall where 150,000 people filed past his casket. On 27 August 1912, Booth's funeral service was held at Olympia London where 40,000 people attended, including Queen Mary, who sat almost unrecognised far to the rear of the great hall. In a letter to Bramwell Booth, King George V wrote: "The nation has lost a great organizer and the poor a whole-hearted and sincere friend." United States President William Taft wrote "[Booth's] long life and great talents were dedicated to the noble work of helping the poor and weak and giving them another chance to attain success and happiness." Media agencies around the world reported on Booth's death, including the Daily Express in the United Kingdom, The South African in South Africa, the Globe and Mail in Canada, and the New York Times in the United States.[21]

Booth's funeral procession began at the Salvation Army's international headquarters as 10,000 uniformed Salvationists fell in behind. Forty Salvation Army brass bands played the "Dead March" from Handel's Saul as the vast procession set off. He was buried with his wife Catherine (died 1890) in Abney Park Cemetery, the main London burial ground for 19th-century non-conformists.[22]

Upon Booth's death, his son, Bramwell Booth, became the second General of The Salvation Army. It was William Booth's intention to have each general choose his successor. However, Generals of the Salvation Army are now elected by the High Council of The Salvation Army.

Legacy

[edit]

In Booth's honour, Vachel Lindsay wrote the poem "General William Booth Enters into Heaven".[23] Charles Ives, who had been Evangeline Booth's neighbour, set the poem to music. In 1990 a diesel locomotive in the British Rail fleet was named 'The William Booth'.

The William Booth rose, developed by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, was named in his honour. William Booth Memorial Training College in Denmark Hill, London, the College for Officer Training of The Salvation Army in the United Kingdom, is named after him,[24] as is the William Booth Primary School in his native Nottingham and William Booth Lane in central Birmingham. Many Salvation Army training colleges, schools, orphanages, hospitals and other institutions around the world bear his name.

Statues of each of the Booths by George Edward Wade were erected on Champion Hill in London, next to the Salvation Army's training college in London in 1929.[25] Replicas of these statues stand in the Mile End Road, close to the site of the first Salvation Army meeting: that of William was unveiled in 1979, and that of Catherine in 2015.

Mount William Booth in Alberta, Canada was named after Booth.[26]

William is remembered (with Catherine) in the Church of England with a commemoration on 20 August.[27]

Family and children

[edit]William Booth and Catherine Mumford were married on 17 June 1855[28] at Stockwell New Chapel, at that time part of Surrey.[29] They had eight children:[30][31]

- Bramwell Booth (8 March 1856 – 16 June 1929)

- Ballington Booth (28 July 1857 – 5 October 1940)

- Kate Booth (18 September 1858 – 9 May 1955)

- Emma Booth (8 January 1860 – 28 October 1903)

- Herbert Booth (26 August 1862 – 25 September 1926)

- Marie Booth (4 May 1864 – 5 January 1937)

- Evangeline Booth (25 December 1865 – 17 July 1950)

- Lucy Booth (28 April 1868 – 18 July 1953)

Gallery

[edit]-

Photograph of Booth, c.1870

-

Plaque on the house in Sneinton in which Booth was born on 10 April 1829

-

Booth in old age

-

William Booth in Japan in 1907

-

Memorial to William and Catherine Booth in Abney Park Cemetery

-

Booth memorial in Battery Park, New York City

Works

[edit]Literature

[edit]- In Darkest England and the Way Out Diggory Press, ISBN 978-1-84685-377-7

- Purity of Heart Diggory Press, ISBN 978-1-84685-376-0

- Boundless Salvation: The Shorter Writings of William Booth, Edited by Andrew M. Eason and Roger J. Green. New York: Peter Lang, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4539-0201-1

- Sergeant-Major Do-Your-Best of Darkington No. I: Sketches of the Inner Life of a Salvation Army Corps 1906

- "Founder Speaks Again" Salvation Army, 1 Dec 1960. ISBN 978-0854120826

Music

[edit]- O Boundless Salvation (1893)[32]

- Send the Fire (1894)[33]

- Bless His Name He Sets Me Free, which was set to a popular music-hall song of the time, Champagne Charlie.[34]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Hattersley 1999, p. 13

- ^ "William Booth Birthplace Museum". Salvation Army. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ^ Hattersley 1999, p. 17

- ^ Hattersley 1999, p. 19

- ^ Hattersley 1999, pp. 23–25

- ^ Hattersley 1999, p. 30

- ^ Herbert Hewitt Stroup (1986). Social Welfare Pioneers. Taylor Trade Publications. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-88229-212-0.

- ^ "Chris Helme - BRIGHOUSE SALVATION ARMY 1887 - 2017".

- ^ Johnson, George D. (2011). What Will A Man Give in Exchange For His Soul. Xlibris. p. 88. ISBN 978-1465380975.

- ^ Coutts, John (1977). The Salvationists. Oxford: A R Mowbray & Co Ltd. p. 85. ISBN 0-264-66071-4.

- ^ a b William Booth – Founder Of The Salvation Army, 'The Salvation Army Australia, Southern Territory - History and Heritage' section website

- ^ Coutts, John (1977). The Salvationists. Oxford, Great Britain: A R Mowbray & Co Ltd. p. 21. ISBN 0-264-66071-4.

- ^ "Belper Research Website: William Booth, Founder of the Salvation Army". www.belper-research.com. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ William Bramwell Booth 1829–1912 His Life and Ministry – A Very Short Biography

- ^ Coutts, John (1977). The Salvationists. Oxford, United Kingdom: A R Mowbray & Co Ltd. p. 23. ISBN 0-264-66071-4.

- ^ Officership in the Salvation Army: A Case Study in Clericalisation Doctoral thesis by Harold Ivor Winston Hill – Victoria University of Wellington (2004)

- ^ Larrson, John (2009). 1929: A Crisis that Shaped The Salvation Army's Future. London: Salvation Books. ISBN 978-0-85412-794-8.

- ^ Hodges, Samuel Horatio General Booth: "the Family", and the Salvation Army: Showing its Rise, Progress, and ... Decline (1890)

- ^ The Booths: The Salvation Army (1878–1890) ourchurch.com

- ^ William Booth: His Life and Ministry, the Gospel Truth website

- ^ "Remembering General William Booth – The Salvation Army NCV DHQ". virginiasalvationarmy.org. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- ^ William Booth's funeral on YouTube

- ^ "General William Booth Enters into Heaven by Vachel Lindsay. Jessie B. Rittenhouse, ed. 1922. The Second Book of Modern Verse". bartleby.com. 19 June 2022.

- ^ William Booth College, Denmark Hill, Geograph

- ^ Darke, Jo, The Monument Guide to England and Wales: A National Portrait in Bronze and Stone, photographs by Jorge Lewinski and Mayotte Magnus, a MacDonald Illustrated Book, London, 1991 pp. 72-73

- ^ "Mount William Booth". cdnrockiesdatabases.ca. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ^ Sandall 1947, p. 7

- ^ Hattersley 1999, p. 73

- ^ L. E. Lauer, 'Clibborn, Catherine Booth- (1858–1955)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, October 2006 accessed 26 May 2010

- ^ D. C. Lamb, 'Booth, (William) Bramwell (1856–1929)', rev. L. E. Lauer, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 21 June 2010

- ^ "Boundless Salvation". Hymntime. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Send the Fire". Hymntime. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ "Stories of inspiration beyond the songs". Lauren Martin (Salvation Army Australia). Retrieved 27 April 2020.

Sources

- Hattersley, Roy (1999), Blood and Fire: William and Catherine Booth and the Salvation Army, Little Brown, ISBN 0-316-85161-2

- Railton, George Scott (1912), The Authoritative Life of General William Booth, George H. Doran

- Sandall, Robert (1947), The History of the Salvation Army Vol.1 1865–78, Thomas Nelson

- Eason, Andrew M.; Roger J. Green, eds. (2012), Boundless Salvation: The Shorter Writings of William Booth, Peter Lang

Further reading

- "General Booth", a biographical portrait by John McLure Hamilton from Men I Have Painted (1921).

- Yaxley, Trevor. 2003. William and Catherine: The Life and Legacy of the Booths: Founders of the Salvation Army. Bethany House.

- Le Feuvre, Cathy. 2013. William and Catherine: A Love Story Told Through Their Letters. Monarch Books.

- Seaman, Matthew (ed). 2016. Darkness and Deliverance: 125 Years of the Darkest England Scheme. Salvo Publishing / Chaordic Creative

External links

[edit]- Biographical Data on General William Booth

- Works by William Booth at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Booth at the Internet Archive

- Works by William Booth at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Books by William Booth

- The Authoritative Life of General William Booth at Project Gutenberg

- Recording of William Booth reading Please Sir, Save Me (1906) – a British Library sound recording (EU users only)

- Christian Today Profile

- Newspaper clippings about William Booth in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1829 births

- 1912 deaths

- 19th-century Christian saints

- 19th-century English clergy

- 19th-century English Christian theologians

- 19th-century Methodist ministers

- 19th-century Protestant theologians

- Anglican saints

- British evangelicals

- Burials at Abney Park Cemetery

- Christian revivalists

- Christianity in London

- Converts to Methodism from Anglicanism

- English evangelicals

- English Methodist ministers

- English Salvationists

- Methodist Church of Great Britain people

- Methodist theologians

- People from Sneinton

- Salvation Army officers

- Family of William Booth