Medieval antisemitism

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

Antisemitism in the history of the Jews in the Middle Ages became increasingly prevalent in the Late Middle Ages.[1] Early instances of pogroms against Jews are recorded in the context of the First Crusade. Expulsions of Jews from cities and instances of blood libel became increasingly common from the 13th to the 15th century. This trend only peaked after the end of the medieval period, and it only subsided with Jewish emancipation in the late 18th and 19th centuries.[2]

Accusations of deicide

In the Middle Ages, religion played a major role in fueling antisemitism. Even though it is not a part of Roman Catholic dogma, many Christians, including many members of the clergy, have held the Jewish people collectively responsible for the killing of Jesus, through the so-called blood curse of Pontius Pilate in the Gospels, among other things.[1]

As stated in the Boston College Guide to Passion Plays, "Over the course of time, Christians began to accept... that the Jewish people as a whole were responsible for killing Jesus. According to this interpretation, both the Jews present at Jesus’ death and the Jewish people collectively and for all time, have committed the sin of deicide, or God-killing. For 1900 years of Christian-Jewish history, the charge of deicide (which was originally attributed by Melito of Sardis) has led to hatred, violence against and murder of Jews in Europe and America."[3]

This accusation was repudiated by the Catholic Church in 1964 under Pope Paul VI issued the document Nostra aetate as a part of Vatican II.

Restrictions to marginal occupations

Among socio-economic factors were restrictions by the authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed many professions to the Jews, pushing them into marginal occupations considered socially inferior, such as tax and rent collecting and moneylending, tolerating them as a "necessary evil". Catholic doctrine of the time held that lending money for interest was a sin, and forbidden to Christians. Not being subject to this restriction, Jews dominated this business. The Torah and later sections of the Hebrew Bible criticise usury but interpretations of the Biblical prohibition vary (the only time Jesus used violence was against money changers taking a toll to enter temple). Since few other occupations were open to them, Jews were motivated to take up money lending, and increasingly became associated with usury by antisemitic Christians.[4] This was said to show Jews were insolent, greedy, usurers, and subsequently led to many negative stereotypes and propaganda. Natural tensions between creditors (typically Jews) and debtors (typically Christians) were added to social, political, religious, and economic strains. Peasants who were forced to pay their taxes to Jews could personify them as the people taking their earnings while remaining loyal to the lords on whose behalf the Jews worked.[5] Jews' role as moneylenders was later used against them, part of the justification in expelling them from England when they lacked the funds to continue lending the king money.

The Black Death

The Black Death plague devastated Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than a half of the population, with Jews being made scapegoats. Rumors spread that they caused the disease by deliberately poisoning wells. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by violence, in particular in the Iberian peninsula and in the Germanic Empire. In Provence, 40 Jews were burnt in Toulon as early as April 1348.[6] "Never mind that Jews were not immune from the ravages of the plague ; they were tortured until they confessed to crimes that they could not possibly have committed.

"The large and significant Jewish communities in such cities as Nuremberg, Frankfurt, and Mainz were wiped out at this time."(1406)[7] In one such case, a man named Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambéry (near Geneva) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice, Toulouse, and elsewhere. In the aftermath of Agimet's "confession", the Jews of Strasbourg were burned alive on 14 February 1349.[8][9]

Although the Pope Clement VI tried to protect them by the 6 July 1348 papal bull and another 1348 bull, several months later, 900 Jews were burnt in Strasbourg, where the plague hadn't yet affected the city.[6] Clement VI condemned the violence and said those who blamed the plague on the Jews (among whom were the flagellants) had been "seduced by that liar, the Devil."[10]

Demonization of the Jews

From around the 12th century through the 19th there were Christians who believed that some (or all) Jews possessed magical powers; some believed that they had gained these magical powers from making a deal with the devil.

Blood libels

On many occasions, Jews were accused of a blood libel, the supposed drinking of blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist. According to the authors of these blood libels, the 'procedure' for the alleged sacrifice was something like this: a child who had not yet reached puberty was kidnapped and taken to a hidden place. The child would be tortured by Jews, and a crowd would gather at the place of execution (in some accounts the synagogue itself) and engage in a mock tribunal to try the child. The child would be presented to the tribunal naked and tied and eventually be condemned to death. In the end, the child would be crowned with thorns and tied or nailed to a wooden cross. The cross would be raised, and the blood dripping from the child's wounds would be caught in bowls or glasses and then drunk. Finally, the child would be killed with a thrust through the heart from a spear, sword, or dagger. Its dead body would be removed from the cross and concealed or disposed of, but in some instances rituals of black magic would be performed on it.[citation needed]

The story of William of Norwich (d. 1144) is often cited as the first known accusation of ritual murder against Jews. The Jews of Norwich, England were accused of murder after a Christian boy, William, was found dead. It was claimed that the Jews had tortured and crucified their victim. The legend of William of Norwich became a cult, and the child acquired the status of a holy martyr. Recent analysis has cast doubt on whether this was the first of the series of blood libel accusations but not on the contrived and antisemitic nature of the tale.[11]

During the Middle Ages blood libels were directed against Jews in many parts of Europe. The believers of these accusations reasoned that the Jews, having crucified Jesus, continued to thirst for pure and innocent blood and satisfied their thirst at the expense of innocent Christian children. Following this logic, such charges were typically made in Spring around the time of Passover, which approximately coincides with the time of Jesus' death.[12]

The story of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255) said that after the boy was dead, his body was removed from the cross and laid on a table. His belly was cut open and his entrails were removed for some occult purpose, such as a divination ritual. The stories of Jews committing blood libel were so widespread that the story of Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln was even used as a source for "The Prioress's Tale," one of the tales included in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales.

Prior to the late 16th century, the Catholic Church officially condemned accusations of blood libel against Jews. The earliest papal bull on the subject, from Innocent IV in 1247, defended the Jews against claims of ritual murder and blood libel that had emerged in the Polish ecclesiastical authorities.[13] In 1272, Pope Gregory X issued a papal bull that synthesized earlier documents and conclusively established the Church's disapproval of blood libel accusations: "Most falsely do these Christians claim that the Jews have secretly and furtively carried away these children and killed them... we order that Jews seized under such a silly pretext be freed from imprisonment."[14] In the late 15th century, however, following the 1475 death of Simon of Trent, a toddler who was claimed to have been ritually murdered by the Jews of Trent, Germanic ecclesiastical authorities began pushing back against the Church's condemnation. Having convicted and executed several prominent Jews, Bishop Johannes Hinderbach of Trent widely disseminated accounts of miracles performed by Simon of Trent, and wrote several letters to Pope Sixtus IV extolling the "devotion and ardor" of pilgrims who had come to worship Simon's cult.[13] For the next three years, Hinderbach continued to lobby jurists and scholars in Rome, and several prominent legal authorities issued rulings in support of both the prosecution's findings and the canonization of Simon.[13] Perhaps due to this popular pressure, Pope Sixtus IV issued a papal bull that declared the trial legal, but did not officially recognize the Jews' guilt, thereby closing off the possibility of Simon's martyrdom.[13] Simon's popularity persisted, however, and in 1583, Pope Gregory XIII added Simon's name to Roman Martyrology, an official source on martyrs of the Roman Catholic Church. This addition, and its corresponding recognition of the local cult of Simon of Trent, halted the Church's condemnations of blood libel accusations until 1759.[15]

Association with misery

In Medieval England, Jews were often associated with feelings of misery, dismay, and sadness. According to Thomas Coryate, "to look like a Jew" meant to look disconnected from oneself. This stereotype pervaded all aspects of life, with David Nirenberg noting that Elizabethan cookbooks emphasised Jewish misery.[16]

Host desecration

Jews were sometimes falsely accused of desecrating consecrated hosts in a reenactment of the Crucifixion by performing a ritual stealing and then stabbing the hosts until the wafer supposedly bled, which became a theological extension of the blood libel accusation that Jews ritually murdered Christian children. This crime was known as host desecration and carried the death penalty.[1]

Disabilities and restrictions

Jews were subject to a wide range of legal disabilities and restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the end of the 19th century. Jews were excluded from many trades, the occupations varying with place and time, and determined by the influence of various non-Jewish competing interests. Often Jews were barred from all occupations but money-lending and peddling, with even these at times forbidden. The number of Jews permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were concentrated in ghettos[17] and were not allowed to own land; they were subject to discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own, were forced to swear special Jewish Oaths, and suffered a variety of other measures, including restrictions on dress.[1]

Clothing

The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 was the first to proclaim the requirement for Jews to wear something that distinguished them as Jews. It could be a coloured piece of cloth in the shape of a star or circle or square, a Jewish hat (already a distinctive style), or a robe. In many localities, members of medieval society wore badges to distinguish their social status. Some badges (such as guild members) were prestigious, while others ostracised outcasts such as lepers, reformed heretics and prostitutes. The local introduction and enforcement of these rules varied greatly. Jews sought to evade the badges by paying what amounted to bribes in the form of temporary "exemptions" to kings, which were revoked and re-paid whenever the king needed to raise funds.[1]

The Crusades

The mobs accompanying the First Crusade, and particularly the People's Crusade of 1096, attacked the Jewish communities in Germany, France, and England, and put many Jews to death. Entire communities, like those of Treves, Speyer, Worms, Troyes, Mainz, and Cologne, were slain during the first Crusade by a mob army. "...on their journey east, wherever the mob of cross-bearing crusaders descended they slaughtered the Jews."[18] About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhenish cities alone between May and July 1096. Before the Crusades the Jews had practically a monopoly of trade in Eastern products, but the closer connection between Europe and the East brought about by the Crusades raised up a class of merchant traders among the Christians, and from this time onward restrictions on the sale of goods by Jews became frequent. The religious zeal fomented by the Crusades at times burned as fiercely against the Jews as against the Muslims, though attempts were made by bishops during the First crusade and the papacy during the Second Crusade to stop Jews from being attacked. Both economically and socially the Crusades were disastrous for European Jews. They prepared the way for the anti-Jewish legislation of Pope Innocent III, and formed the turning point in the medieval history of the Jews.

In the County of Toulouse (now part of southern France) Jews were received on good terms until the Albigensian Crusade. Toleration and favour shown to the Jews was one of the main complaints of the Roman Church against the Counts of Toulouse. Following the Crusaders' successful wars against Raymond VI and Raymond VII, the Counts were required to discriminate against Jews like other Christian rulers. In 1209, stripped to the waist and barefoot, Raymond VI was obliged to swear that he would no longer allow Jews to hold public office. In 1229 his son Raymond VII, underwent a similar ceremony where he was obliged to prohibit the public employment of Jews, this time at Notre Dame in Paris. Explicit provisions on the subject were included in the Treaty of Meaux (1229). By the next generation a new, zealously Catholic, ruler was arresting and imprisoning Jews for no crime, raiding their houses, seizing their cash, and removing their religious books. They were then released only if they paid a new "tax". A historian has argued that organised and official persecution of the Jews became a normal feature of life in southern France only after the Albigensian Crusade because it was only then that the Church became powerful enough to insist that measures of discrimination be applied.[19]

Expulsions from England, France, Germany, Spain and Portugal

In the Middle Ages in Europe persecutions and formal expulsions of Jews were liable to occur at intervals, although it should be said that this was also the case for other minority communities, whether religious or ethnic. There were particular outbursts of riotous persecution in the Rhineland massacres of 1096 in Germany accompanying the lead-up to the First Crusade, many involving the crusaders as they travelled to the East. There were many local expulsions from cities by local rulers and city councils. In Germany the Holy Roman Emperor generally tried to restrain persecution, if only for economic reasons, but he was often unable to exert much influence.[20][21] As late as 1519, the Imperial city of Regensburg took advantage of the recent death of Emperor Maximilian I to expel its 500 Jews.[22]

The practice of expelling the Jews accompanied by confiscation of their property, followed by temporary readmissions for ransom, was utilized to enrich the French crown during 12th-14th centuries. The most notable such expulsions were: from Paris by Philip Augustus in 1182, from the entirety of France by Louis IX in 1254, by Philip IV in 1306, by Charles IV in 1322, by Charles VI in 1394.

To finance his war to conquer Wales, Edward I of England taxed the Jewish moneylenders. When the Jews could no longer pay, they were accused of disloyalty. Already restricted to a limited number of occupations, the Jews saw Edward abolish their "privilege" to lend money, choke their movements and activities and were forced to wear a yellow patch. The heads of Jewish households were then arrested, over 300 of them taken to the Tower of London and executed, while others killed in their homes. The complete banishment of all Jews from the country in 1290 led to thousands killed and drowned while fleeing and the absence of Jews from England for three and a half centuries, until 1655, when Oliver Cromwell reversed the policy.

In 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile issued General Edict on the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain and many Sephardi Jews fled to the Ottoman Empire, some to Palestine, to avoid the Spanish Inquisition.

The Kingdom of Portugal followed suit and in December 1496, it was decreed that any Jew who did not convert to Christianity would be expelled from the country. However, those expelled could only leave the country in ships specified by the King. When those who chose expulsion arrived at the port in Lisbon, they were met by clerics and soldiers who used force, coercion, and promises in order to baptize them and prevent them from leaving the country. This period of time technically ended the presence of Jews in Portugal. Afterwards, all converted Jews and their descendants would be referred to as "New Christians" or Marranos (lit. "pigs" in Spanish), and they were given a grace period of thirty years in which no inquiries into their faith would be allowed; this was later to be extended to end in 1534. A popular riot in 1504 would end in the death of two thousand Jews; the leaders of this riot were executed by Manuel.

Anti-Judaism and the Reformation

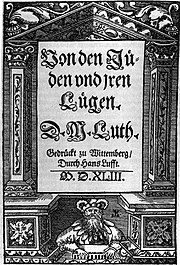

Martin Luther, an Augustinian monk and an ecclesiastical reformer whose teachings inspired the Protestant Reformation, wrote antagonistically about Jews in his book On the Jews and their Lies, which describes the Jews in extremely harsh terms, excoriates them, and provides detailed recommendations for a pogrom against them and their permanent oppression and/or expulsion. At one point in On the Jews and Their Lies, Martin Luther goes even as far to write "that we are at fault in not slaying them." Notably, Luther's intense hostility towards Jews moved away from a long-standing custom, developed by Augustine in the early fifth century, of assigning Jews the protected status as relics of the pre-Christ Biblical past who are thus useful to Christians and should not face expulsion. Luther's writings instead instigated another wave of political expulsions of Jewish populations from German localities, in the years immediately succeeding the release of “On the Jews and Their Lies” and for a few decades after the fact.[23] According to Paul Johnson, Luther's book "may be termed the first work of modern anti-Semitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust."[24] In his final sermon shortly before his death, however, Luther preached "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord."[25] Still, Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian antisemitism.

Medieval antisemitic art

During the Middle Ages, much art was created by Christians that depicted Jews in a fictional or stereotypical manner; the great majority of narrative religious Medieval art depicted events from the Bible, where the majority of persons shown had been Jewish. But the extent to which this was emphasized in their depictions varied greatly. Some of this art was based on preconceived notions about how Jews dressed or looked, as well as the “sinning” acts which Christians believed that they committed.[26] Visual art in particular expressed these ideas with a clear polemic edge. On the Westlettner of the Naumberg Cathedral, 13 of the 31 figures featured on the original set of reliefs are Jewish, clearly demarcated as such by their Jewish hats. As with much other medieval art of the Jews,[27] many of the 13 are depicted as in some way being complicit or directly aiding the Crucifixion of Christ, furthering the charge of Jewish deicide. With that in mind, however, some scholars argue that Naumberg's reliefs are unusually not anti-Jewish for their time period in their portrayal of the Jews, as not all of them are sculpted as unambiguously evil or malicious.[28] Comparing that to the caricatures in the west facade of the abbey church of St-Gilles-du-Gard, Naumberg's images do seem relatively tame. Here, Jews are displayed in some of the most typical anti-Jewish iconography of the time, with protruding jaws and hooked noses. Their haggardly, poor appearance is contrasted with the non-Jews of the image, including Roman guards, who are presented with a degree of fashion and status through their capes and typical tunics and similar attire.[28] Another iconic symbol of this era was Ecclesia and Synagoga, a pair of statues personifying the Christian Church (Ecclesia) next to her predecessor, the Nation of Israel (synagoga). The latter was often displayed blindfolded and carrying a tablet of the law sliping from her hand, sometimes also bearing a broken staff, whereas Ecclesia was standing upright with a crowned head, a chalice and a staff adorned with the cross.[29] This was often as a result of a misinterpretation of the Christian doctrine of Supersessionism involving a replacement of the "old" covenant given to Moses by the "new" covenant of Christ, which medieval Christians took to mean that the Jews had fallen out of God's favour.

Jews as enemies of Christians

Medieval Christians believed in the idea of Jewish "stubbornness", which correlated to many characteristics of the Jewish people. Specifically, Jews did not believe that Christ was the Messiah, a savior. This idea contributed to the stereotype that Jews were stubborn but also extended further in that the Jews dismissed Christ so far that they decided to murder him by nailing him to a cross. Jews were, therefore, marked as the "enemies of Christians" and "Christ-killers."[26]

The notion behind Jews as Christ-killers was one of the main inspirations behind antisemitic portrayals of Jews in Christian art. For example, in one piece, a Jew is placed in between the pages of a Bible[clarify], while sacrificing a lamb with a knife. The lamb is meant to represent Christ, which serves to reveal how Christ died at the hands of the Jewish people.[citation needed]

Jews as devil-like

Further, according to Medieval Christians, anyone who did not agree with their ideas of faith, including the Jewish people, were automatically assumed to be friendly with the devil and simultaneously condemned to hell. Therefore, in many portrayals of Christian art, Jews are made out to resemble demons or interact with the devil. This is meant to not only portray Jews as ugly, evil, and grotesque but also to establish that demons and Jews are innately similar. Jews would also be placed in front of hell to further showcase that they are damned.[26]

Stereotypical Jewish appearances

By the twelfth century, the concept of a "stereotypical Jew" was widely known. A stereotypical Jew was usually a male with a heavy beard, a hat, and a large, crooked nose, all of which were significant identifiers for someone who was Jewish. These notions were portrayed in medieval art, which ultimately ensured that a Jew could easily be identified. The idea behind a stereotypical Jew was to primarily portray a Jew as an ugly creature which is to be avoided and feared.[26]

See also

- Antisemitism

- Geography of antisemitism

- History of antisemitism

- Antisemitism in Europe

- Antisemitism in Christianity

- Christianity and Judaism

- History of the Jews in Europe

- Antisemitism in the Arab world

- Antisemitism in Islam

- History of the Jews under Muslim rule

- Islamic–Jewish relations

- Relations between Nazi Germany and the Arab world

- Jacob Barnet affair

- Jewish history

- History of the Jews in the Middle Ages

- Relations between Eastern Orthodoxy and Judaism

- Catholic Church and Judaism

- Religious antisemitism

References

- ^ a b c d e Johannes, Fried (2015) p. 287-289 The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Anti-Semitism In Medieval Europe Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Paley, Susan and Koesters, Adrian Gibbons, eds. "A Viewer's Guide to Contemporary Passion Plays" Archived March 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 12, 2006.

- ^ Yuval-Naeh, Avinoam (7 December 2017). "England, Usury and the Jews in the Mid-Seventeenth Century". Journal of Early Modern History. 21 (6): 489–515. doi:10.1163/15700658-12342542. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Religious Discrimination, Berkman Center - Harvard Law School [dead link]

- ^ a b See Stéphane Barry and Norbert Gualde, La plus grande épidémie de l'histoire ("The greatest epidemics in history"), in L'Histoire magazine, n°310, June 2006, p.47 (in French)

- ^ Johannes, Fried (2015) p. 421. The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Hertzberg, Arthur and Hirt-Manheimer, Aron. Jews: The Essence and Character of a People, HarperSanFrancisco, 1998, p.84. ISBN 0-06-063834-6

- ^ Johannes, Fried (2015) p. 420. The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Lindsey, Hal (1990). The Road to Holocaust. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-0-553-34899-6.

- ^ Bennett, Gillian (2005), "Towards a revaluation of the legend of 'Saint' William of Norwich and its place in the blood libel legend". Folklore, 116(2), pp 119-21.

- ^ Ben-Sasson, H.H., Editor; (1969). A History of The Jewish People. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 0-674-39731-2 (paper).

- ^ a b c d Teter, Magda. "The Death of Little Simon and the Trial of Jews in Trent." In Blood Libel: On the Trail of an Antisemitic Myth, 43-88. N.p.: Harvard University Press, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvt1sj9x.8.

- ^ Pope Gregory X. "Letter on Jews against the Blood Libel." 1272. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/gregory-x-letter-about-jews-against-the-blood-libel.

- ^ Kohl, Jeanette. "A Murder, a Mummy, and a Bust: The Newly Discovered Portrait of Simon of Trent at the Getty." Getty Research Journal, no. 10 (2018). Accessed October 10, 2022. https://books.google.com/books?id=dAldDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA40#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ Nirenberg, David. Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition.

- ^ Chazan, Robert (2010). Reassessing Jewish Life in Medieval Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 252.

- ^ Johannes, Fried (2015) p. 160. The Middle Ages. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Michael Costen, The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade, p 38

- ^ Anti-Semitism. Jerusalem: Keter Books. 1974. ISBN 9780706513271.

- ^ "Map of Jewish expulsions and resettlement areas in Europe". Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida. A Teacher's Guide to the Holocaust. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ Wood, Christopher S., Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape, p. 251, 1993, Reaktion Books, London, ISBN 0948462469

- ^ David Nirenberg. "Anti-Judaism", W.W. Norton & Company, 2013, p.262. ISBN 978-0-393-34791-3

- ^ Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews, HarperCollins Publishers, 1987, p.242. ISBN 5-551-76858-9

- ^ Luther, Martin. D. Martin Luthers Werke: kritische Gesamtausgabe, Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger, 1920, Vol. 51, p. 195.

- ^ a b c d Strickland, Debra Higgs (2003). Saracens, Demons, and Jews: making monsters in Medieval art. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Pontius Pilate, anti-Semitism, and the Passion in medieval art. 2009-12-01.

- ^ a b Merback, Mitchell (2008). Beyond the Yellow Badge Anti-Judaism and Antisemitism in Medieval and Early Modern Visual Culture. ISBN 978-90-04-15165-9. OCLC 923533086.

- ^ From Notre Dame to Prague, Europe’s anti-Semitism is literally carved in stone Jewish Telegraphic Agency, March 20, 2015