New Model Army

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2020) |

| New Model Army | |

|---|---|

The Souldiers Catechiſme:[1] Religious justification for the New Model Army | |

| Active | 1645–1660 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Type | Army |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-Chief | Thomas Fairfax, George Monck |

| Notable commanders | Oliver Cromwell, Thomas Pride, John Lambert, Henry Ireton, William Lockhart |

The New Model Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms in that members were liable for service anywhere in the country, rather than being limited to a single area or garrison. To establish a professional officer corps, the army's leaders were prohibited from having seats in either the House of Lords or House of Commons. This was to encourage their separation from the political or religious factions among the Parliamentarians.

The New Model Army was raised partly from among veteran soldiers who already had deeply held Puritan religious beliefs, and partly from conscripts who brought with them many commonly held beliefs about religion or society. Many of its common soldiers therefore held dissenting or radical views unique among English armies. Although the Army's senior officers did not share many of their soldiers' political opinions, their independence from Parliament led to the Army's willingness to contribute to both Parliament's authority and to overthrow the Crown, and to establish a Commonwealth of England from 1649 to 1660, which included a period of direct military rule. Ultimately, the Army's generals (particularly Oliver Cromwell) could rely on both the Army's internal discipline and its religious zeal and innate support for the "Good Old Cause" to maintain an essentially dictatorial rule[citation needed].

Foundation

The forces raised in 1642 by both Royalists and Parliamentarians were based on part-time militia known as Trained bands. Founded in 1572, these were organised by county, controlled by Lord-lieutenants appointed by the king, and constituted the only permanent military force in the country. The muster roll of February 1638 shows wide variations in size, equipment and training; the largest and best trained were based in London with 8,000, later increased to 20,000.[2] When the First English Civil War began in August 1642, many of the largest militia were based in Parliamentarian areas like London, while Royalist counties like Shropshire or Glamorgan had fewer than 500 men.[3]

The weakness of this system was the reluctance of locally-raised troops to serve outside their "home" areas, a problem for both sides during the war. On 19 November 1644, the Parliamentarian Eastern Association announced that they could no longer meet the cost of maintaining their forces, which then comprised about half the field force available to Parliament. In response, the Committee of Both Kingdoms conducted a wide-ranging review of further military needs and recommended the establishment of a centralised, professional force. On 17 February 1645, the New Model Army Ordinance became law, with Fairfax being appointed Captain General, or commander in chief, and Philip Skippon being appointed Major General of the Foot.[4][5]

The review coincided with increasing dissatisfaction as to the conduct of certain senior commanders; in July 1644, a Parliamentarian force under Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell secured control of Northern England by victory at Marston Moor. However, this was offset first by defeat at Lostwithiel in September, then lack of decisiveness at the Second Battle of Newbury in October. The two commanders involved, Essex and Manchester, were accused by many in Parliament of lacking commitment, a group that included moderates like Sir William Waller as well as radicals like Cromwell.[6]

In December 1644, Sir Henry Vane introduced the Self-denying Ordinance, requiring those holding military commissions to resign from Parliament. As members of the House of Lords, Manchester and Essex were automatically removed, since unlike MPs they could not resign their titles, although they could be re-appointed, 'if Parliament approved.'[7] Although delayed by the Lords, the Ordinance came into force on 3 April 1645. Since Cromwell was MP for Cambridge, command of the cavalry was initially given to Colonel Bartholomew Vermuyden, a former officer in the Eastern Association who was of Dutch origin and wanted to return home.[8] Fairfax asked that Cromwell be appointed Lieutenant General of the Horse in place of Vermuyden, making him one of two original exceptions to the Self-denying Ordinance, the other being Sir William Brereton, commander in Cheshire. They were allowed to serve under a series of three-month temporary commissions that were continually extended.[9]

Other Parliamentarian forces were consolidated into two regional armies, the Northern Association under Sydenham Poyntz and Western Association under Edward Massey. Their focus was to secure these areas and reduce any remaining Royalist garrisons, as well as providing local support for offensives conducted by the New Model; some of their regiments were later incorporated into the Army during and after the Second English Civil War.

Establishment and character

Parliament authorised an Army of 22,000 soldiers, most of whom came from three existing Parliamentarian armies; that commanded by the Earl of Essex, Waller's Southern Association and the Eastern Association under the Earl of Manchester.[10] It comprised 6,600 cavalry, divided into eleven units of 600 men, 14,400 foot, comprising twelve regiments of 1,200 men, and 1,000 dragoons. Originally each regiment of cavalry had a company of dragoons attached, but at the urging of Fairfax on 1 March they were formed into a separate unit commanded by Colonel John Okey.[11] Although the cavalry regiments were already up to strength, the infantry was severely understrength and in May 1645 was still 4,000 men below the approved level.[12]

By creating fewer but larger regiments, the re-organisation greatly reduced the requirement for officers and senior NCOs. Fairfax had more than double the number of officers available for his 200 vacancies and those deemed surplus to requirements were either discharged or persuaded to re-enlist at a lower rank.[4] Essex and Manchester raised objections to around 30% of those on the list, for reasons that are still debated, but ultimately only five changes were approved.[13] In addition, several Scots officers refused to take up their appointments, including John Middleton, originally colonel of the Second Regiment of Horse.[14]

The standard daily pay was 8 pence for infantry and 2 shillings for cavalry, who also had to supply their own horses, while the administration of the Army was more centralised, with improved provision of adequate food, clothing and other supplies. At the same time, recruits were also supposed to be motivated by religious fervour, as demonstrated in the "Soldier's catechism",written by Robert Ram.[1] On 9 June 1645, Sir Samuel Luke, one of the officers discharged, wrote the Army was "the bravest for bodies of men, horse and arms so far as the common soldiers as ever I saw in my life". However, he later complained many soldiers were drunk and their officers were often indistinguishable from enlisted men.[15]

The extent to which the Army can be seen as a hotbed of religious and political radicalism is disputed, particularly since many of those now viewed as radicals, like Thomas Horton or Thomas Pride, were not considered such at the time. It is generally agreed that Fairfax, himself a moderate Presbyterian, sought to achieve a balance, while Essex and Manchester tried to remove those they viewed as unsuitable.[16] What is debated is whether they did so for military reasons, favouring the retention of established officer cadres, or to eliminate personal enemies and those considered too radical. Ultimately they failed and Fairfax successfully achieved his objective.[17]

Name

The Oxford English Dictionary dated the earliest use of the phrase "New Model Army" to the works of the Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle in 1845, and the exact term does not appear in 17th- or 18th-century documents. Records from February 1646 refer to the "New Modelled Army"—the idiom of the time being to refer to an army that was "new-modelled" rather than appending the word "army" to "new model".[18]

Original order of battle

| Type | Colonel | Origin | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Horse | Sir Thomas Fairfax's Regiment | Army of the Eastern Association | Formerly part of Oliver Cromwell's double regiment of 'Ironsides'. Sir Thomas Fairfax's Lifeguard (formerly the Earl of Essex's Lifeguard troop) formed extra senior troop. |

| Horse | Edward Whalley's Regiment | Army of the Eastern Association | Formerly part of Oliver Cromwell's double regiment of 'Ironsides'. Richard Baxter served as chaplain July 1645 – July 1646. |

| Horse | Charles Fleetwood's Regiment | Army of the Eastern Association | Said to have many Independents in its ranks |

| Horse | Nathaniel Rich's Regiment | Army of the Eastern Association | Formerly the Earl of Manchester's Regiment. Originally intended for Algernon Sydney, who declined the appointment due to health concerns. Rich had earlier been rejected by the Commons for a colonelcy.[19] |

| Horse | Bartholomew Vermuyden's Regiment | Army of the Eastern Association | Taken over by Oliver Cromwell after Naseby. Vermuyden, one of the last non-English regimental commanders, resigned in July 1645. |

| Horse | Richard Graves' Regiment | Army of the Earl of Essex | Formerly the Earl of Essex's Regiment. After June 1647, it was commanded by Adrian Scrope. It was disbanded after 1649 Leveller Mutiny at Burford. |

| Horse | Sir Robert Pye's Regiment | Army of the Earl of Essex | Originally intended for Nathaniel Rich, whose nomination was the only colonelcy rejected by the Commons, though he later received a commission when Algernon Sydney declined his nomination. Pye replaced by Matthew Tomlinson in 1647. |

| Horse | Thomas Sheffield's Regiment | Army of the Earl of Essex | Sheffield replaced by Thomas Harrison in 1647 |

| Horse | John Butler's Regiment | Army of the Southern Association | Originally intended for John Middleton, who declined so he could serve in Scotland against the Earl of Montrose. Butler replaced by Thomas Horton in 1647 |

| Horse | Henry Ireton's Regiment[tablenote 1] | Army of the Southern Association | |

| Horse | Edward Rossiter's Regiment | Newly raised | Originally intended to serve in Lincolnshire. Rossiter was replaced by Philip Twisleton in 1647 |

| Dragoons | John Okey's Regiment[tablenote 1] | Mixed | Later converted to a regiment of Horse |

| Foot | Sir Thomas Fairfax's Regiment | Army of the Earl of Essex | Originally the Earl of Essex's Regiment but contained some companies from the Eastern Association |

| Foot | Robert Hammond's Regiment | Army of the Eastern Association | Originally intended for Lawrence Crawford, who refused to serve in the New Model Army |

| Foot | Edward Montagu's Regiment[tablenote 1] | Army of the Eastern Association | Montague withdrew from the Army when he was elected MP for Huntingdonshire in October 1645. Replaced by John Lambert. |

| Foot | John Pickering's Regiment[tablenote 2] | Army of the Eastern Association | Pickering died of an illness at Antre and was replaced by John Hewson in December 1646. |

| Foot | Thomas Rainsborough's Regiment[tablenote 2] | Army of the Eastern Association | Originally intended for Colonel Ayloff, who refused to serve in New Model Army. |

| Foot | Sir Philip Skippon's Regiment | Army of the Earl of Essex | |

| Foot | Richard Fortescue's Regiment | Army of the Earl of Essex | Fortescue replaced by John Barkstead in 1647. This regiment suffered the deaths of three successive lieutenant colonels in battle. It was unusual for such high-ranking officers to die. |

| Foot | Edward Harley's Regiment | Army of the Earl of Essex | Originally intended for Colonel Harry Barclay, a Scottish colonel. Harley did not serve in 1645, as he was still recovering from wounds. Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Pride commanded in his absence, and succeeded to command in 1647. |

| Foot | Richard Ingoldsby's Regiment | Army of the Earl of Essex | |

| Foot | Walter Lloyd's Regiment | Army of the Earl of Essex | Originally intended for Colonel Edward Aldrich, who refused to command this particular regiment because it was composed of soldiers from many different precursor regiments. Lloyd died in battle in June 1645 and was replaced by William Herbert, who was in turn replaced by Robert Overton in 1647. |

| Foot | Hardress Waller's Regiment | Army of the Southern Association | Originally intended for Scottish colonel James Holborne |

| Foot | Ralph Weldon's Regiment | Army of the Southern Association | Originally the "Kentish Regiment". Weldon was replaced by Robert Lilburne in spring 1646 when Weldon was appointed governor of Plymouth. Weldon's Lieutenant Colonel, Nicholas Kempson, was passed over for promotion and undermined Lilburne's command. |

Dress, equipment and tactics

Horse

The New Model Army's elite troops were its Regiments of Horse. They were armed and equipped in the style known at the time as harquebusiers, rather than as heavily armoured cuirassiers. They wore a back-and-front breastplate over a buff leather coat, which itself gave some protection against sword cuts, and normally a lobster-tailed pot helmet with a movable three-barred visor, and a bridle gauntlet on the left hand. The sleeves of the buff coats were often decorated with strips of braid, which may have been arranged in a regimental pattern. Leather "bucket-topped" riding boots gave some protection to the legs.[citation needed]

Regiments were organised into six troops, of one hundred troopers plus officers, non-commissioned officers and specialists (drummers, farriers etc.). Each troop had its own standard, 2 feet (61 cm) square. On the battlefield, a regiment was normally formed as two "divisions" of three troops, one commanded by the regiment's colonel (or the major, if the colonel was not present), the other by the lieutenant colonel.[20]

Their discipline was markedly superior to that of their Royalist counterparts. Cromwell specifically forbade his men to gallop after a fleeing enemy, but demanded they hold the battlefield. This meant that the New Model cavalry could charge, break an enemy force, regroup and charge again at another objective. On the other hand, when required to pursue, they did so relentlessly, not breaking ranks to loot abandoned enemy baggage as Royalist horse often did.[21]

Dragoons

The New Model Army contained one regiment of dragoons, of twelve companies each of one hundred men, under Colonel John Okey. Dragoons were mounted infantry, and wore much the same uniform as musketeers although they probably wore stout cloth gaiters to protect the legs while riding. They were armed with flintlock "snaphaunces" rather than the matchlock muskets carried by the infantry.

On the battlefield, their major function was to clear enemy musketeers from in front of their main position. At the Battle of Naseby, they were used to outflank enemy cavalry.[1]

They were also useful in patrolling and scouting. In sieges, they were often used to assault breaches carrying flintlock carbines and grenades. The storming party were sometimes offered cash payments, as this was a very risky job. Once the forlorn hope established a foothold in the enemy position, the infantry followed them with their more cumbersome pikes and matchlock muskets.

In 1650, Okey's dragoons were converted into a regiment of horse. It appears that after that date, unregimented companies of dragoons raised from the Militia and other sources were attached to the regiments of horse and foot as required. This was the case at the Battle of Dunbar on 3 September 1650.[22]

Foot

The Regiments of Foot consisted of ten companies, in which musketeers and pikemen were mixed, at least on the march. Seven companies consisted of one hundred soldiers, plus officers, specialists and so on, and were commanded by captains. The other three companies were nominally commanded by the regiment's colonel, lieutenant colonel and major, and were stronger (200, 160 and 140 ordinary soldiers respectively).[23]

The regiments of foot were provided with red coats. Red was chosen because uniforms were purchased competitively from the lowest bidder, and Venetian red was the least expensive dye. Those used by the various regiments were distinguished by differently coloured linings, which showed at the collar and ends of the sleeves, and generally matched the colours of the regimental and company standards. In time, they became the official "Facing colour".[24] On some occasions, regiments were referred to, for example, as the "blue" regiment or the "white" regiment from these colours, though in formal correspondence they were referred to by the name of their colonel. Each company had its own standard, 6 feet (180 cm) square. The colonel's company's standard was plain, the lieutenant colonel's had a cross of Saint George in the upper corner nearest the staff, the major's had a "flame" issuing from the cross, and the captains' standards had increasing numbers of heraldic decorations, such as roundels or crosses to indicate their seniority.

The New Model Army always had two musketeers for each pikeman,[25] though depictions of battles show them present in equal numbers.[a] On the battlefield, the musketeers lacked protection against enemy cavalry, and the two types of foot soldier supported each other. For most siege work, or for any action in wooded or rough country, the musketeer was generally more useful and versatile. Musketeers were often detached from their regiments, or "commanded", for particular tasks.

Pikemen, when fully equipped, wore a pot helmet, back- and breastplates over a buff coat, and often also armoured tassets to protect the upper legs. They carried a sixteen-foot pike, and a sword. The heavily burdened pikeman usually dictated the speed of the Army's movement. They were frequently ordered to discard the tassets, and individual soldiers were disciplined for sawing a foot or two from the butts of their pikes,[26] although senior officers were recommended to make the men accustomed to marching with heavy loads by regular route marches. In irregular fighting in Ireland, the New Model temporarily gave up the pike.[27] In battle, the pikemen were supposed to project a solid front of spearheads, to protect the musketeers from cavalry while they reloaded. They also led the infantry advance against enemy foot units, when things came to push of pike.[28]

The musketeers wore no armour, at least by the end of the Civil War,[29] although it is not certain that none had iron helmets at the beginning. They wore a bandolier from which were suspended twelve wooden containers, each with a ball and measured charge of powder for their matchlock muskets. These containers are sometimes referred to as the "Twelve Apostles".[30] According to one source, they carried 1 lb of fine powder, for priming, to 2 lbs of lead and 2 lbs of ordinary powder, the actual charging powder, for 3 lbs of lead.[31] They were normally deployed six ranks deep, and were supposed to keep up a constant fire by means of the countermarch—either by introduction whereby the rear rank filed to the front to fire a volley, or by retroduction where the front rank fired a volley then filed to the rear. By the time that they reached the front rank again, they should have reloaded and been prepared to fire. At close quarters, there was often no time for musketeers to reload, and they used their musket butts as clubs. They carried swords, but these were often of inferior quality, and ruined by use for cutting firewood.[32] Bayonets were not introduced into European armies until the 1660s and so were not part of a musketeer's equipment.

Artillery

The establishment of the New Model Army's artillery varied over time, and the artillery was administered separately from the Horse and Foot. At the Army's formation, Thomas Hammond (brother of Colonel Robert Hammond who commanded a Regiment of Foot) was appointed Lieutenant General of the Ordnance.[33] Much of the artillery was captured from the Royalists in the aftermath of the Battle of Naseby and the storming of Bristol.

The establishment of the New Model also included at least two companies of "firelocks" or fusiliers, who wore "tawny coats" instead of red,[34] commanded initially by Major John Desborough.[33] They were used to guard the guns and ammunition wagons, as it was obviously undesirable to have matchlock-armed soldiers with lighted matches near the gunpowder barrels.

The artillery was used to most effect in sieges, where its role was to blast breaches in fortifications for the infantry to assault. Cromwell and the other commanders of the Army were not trained in siege warfare and generally tried to take fortified towns by storm rather than go through the complex and time-consuming process of building earthworks and trenches around it so that batteries of cannon could be brought close to the walls to pound it into surrender. The Army generally performed well when storming fortifications, for example at the siege of Drogheda, but paid a heavy price at Clonmel when Cromwell ordered them to attack a well-defended breach.[35]

Logistics

The New Model did not use tents, instead being quartered in whatever buildings (houses, barns etc.) were available, until they began to serve in the less populated areas of the countries of Ireland and Scotland. In 1650, their tents were each for six men, a file, who carried the tents in parts.[36] In campaigns in Scotland, the troops carried with them seven days' rations, consisting exclusively of biscuit and cheese.[37]

Civil War campaigns

The Army took the field in late April or May, 1645. After an attempt to raise the siege of Taunton was abandoned, the Army began a siege of Oxford, sending a detachment of one regiment of cavalry and four of infantry to reinforce the defenders of Taunton. After the Royalists captured Leicester, Fairfax was ordered to leave Oxford and march north to confront the King's army. On 14 June, the New Model destroyed King Charles' smaller but veteran army at the Battle of Naseby. Leaving the Scots and locally raised forces to contain the King, Fairfax marched into the West Country, where they destroyed the remaining Royalist field army at Langport on 10 July. Thereafter, they reduced the Royalist fortresses in the west and south of England. The last fortress in the west surrendered in early 1646, shortly before Charles surrendered himself to a Scottish army and hostilities ended.[38]

Revolutionary politics and the "Agreement of the People"

Having won the First Civil War, the soldiers became discontented with the Long Parliament, for several reasons. Firstly, they had not been paid regularly – pay was weeks in arrears – and on the end of hostilities, the conservative MPs in Parliament wanted to either disband the Army or send them to fight in Ireland without addressing the issue of back pay. Secondly, the Long Parliament refused to grant the soldiers amnesty from prosecution for any criminal acts they had been ordered to commit in the Civil War. The soldiers demanded indemnity as several soldiers were hanged after the war for crimes such as stealing horses for use by the cavalry regiments. Thirdly, seeing that most Parliamentarians wanted to restore the King without major democratic reforms or religious freedom,[b] many soldiers asked why they had risked their lives in the first place, a sentiment that was strongly expressed by their elected representatives.

Two representatives, called Agitators, were elected from each regiment. The Agitators, with two officers from each regiment and the Generals, formed a new body called the Army Council. At a meeting ("rendezvous") held near Newmarket, Suffolk on 4 June 1647 this council issued "A Solemne Engagement of the Army, under the Command of his Excellency Sir Thomas Fairfax" to Parliament on 8 June making their concerns known, and also detailing the constitution of the Army Council so that Parliament would understand that the discontent was Army wide and had the support of both officers and other ranks. This Engagement was read out to the Army at a general Army rendezvous on 5 June.[citation needed]

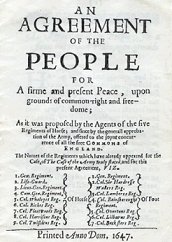

Having come into contact with ideas from the radical movement called the Levellers, the troops of the Army proposed a revolutionary new constitution named the Agreement of the People, which called for almost universal male suffrage, electoral boundary reform, power to rest with a Parliament elected by the people every two years, religious freedom, and an end to imprisonment for debt.[citation needed]

Increasingly concerned at the failure to pay their wages and by political manoeuvrings by King Charles I and by some in Parliament, the army marched slowly towards London over the next few months. In late October and early November at the Putney Debates, the Army debated two different proposals. The first was the Agreement of the People; the other was the Heads of Proposals, put forward by Henry Ireton for the Army Council. This constitutional manifesto included the preservation of property rights and would maintain the privileges of the gentry. At the Putney Debates, it was agreed to hold three further rendezvous.[citation needed]

Second English Civil War

The army remained under control and intact, so it was able to take the field when the Second English Civil War broke out in July 1648. The New Model Army routed English royalist insurrections in Surrey and Kent, and in Wales, before crushing a Scottish invasion force at the Battle of Preston in August.

Many of the Army's radicals now called for the execution of the King, whom they called "Charles Stuart, that man of blood". The majority of the Grandees realised that they could neither negotiate a settlement with Charles I, nor trust him to refrain from raising another army to attack them, so they came reluctantly to the same conclusion as the radicals: they would have to execute him. After the Long Parliament rejected the Army's Remonstrance[c] by 125 to 58, the Grandees decided to reconstitute Parliament so that it would agree with the Army's position. On 6 December 1648, Colonel Thomas Pride instituted Pride's Purge and forcibly removed from the House of Commons all those who were not supporters of the religious independents and the Grandees in the Army. The much-reduced Rump Parliament passed the necessary legislation to try Charles I. He was found guilty of high treason by the 59 Commissioners and beheaded on 30 January 1649.

Now that the twin pressures of Royalism and those in the Long Parliament who were hostile to the Army had been defeated, the divisions in the Army present in the Putney Debates resurfaced. Cromwell, Ireton, Fairfax and the other Grandees were not prepared to countenance the Agitators' proposals for a revolutionary constitutional settlement. This eventually brought the Grandees into conflict with those elements in the New Model Army who did.

During 1649, there were three mutinies over pay and political demands. The first involved 300 infantrymen of Colonel John Hewson's regiment, who declared that they would not serve in Ireland until the Levellers' programme had been realised. They were cashiered without arrears of pay, which was the threat that had been used to quell the mutiny at the Corkbush Field rendezvous.

In the Bishopsgate mutiny, soldiers of the regiment of Colonel Edward Whalley stationed in Bishopsgate, in London, made demands similar to those of Hewson's regiment. They were ordered out of London.[citation needed]

Less than two weeks later, there was a larger mutiny involving several regiments over pay and political demands. After the resolution of the pay issue, the Banbury mutineers, consisting of 400 soldiers with Leveller sympathies under the command of Captain William Thompson, continued to negotiate for their political demands. They set out for Salisbury in the hope of rallying support from the regiments billeted there. Cromwell launched a night attack on 13 May, in which several mutineers perished, but Captain Thompson escaped, only to be killed in another skirmish near the Diggers community at Wellingborough. The rest were imprisoned in Burford Church until three were shot in the Churchyard on 17 May. With the failure of this mutiny, the Levellers' power base in the New Model Army was destroyed.

Ireland

Later that year, on 15 August 1649, the New Model Army landed in Ireland to start the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland. The soldiers in this expeditionary force were not the first New Model soldiers to fight in Ireland (many hundreds had fought in the major battles of the previous years) but the scale of the 1649 deployment far exceeded all earlier efforts. Many soldiers were reluctant to serve in this campaign, as Ireland had a bad reputation amongst English soldiers, and regiments had to draw lots to decide who would go on the expedition.[citation needed]

The politically and religiously disunited Royalist and Catholic coalition they met in Ireland were at a major disadvantage against the New Model Army. After the shock defeats at Rathmines and Drogheda, many of the Royalist soldiers opposing the Parliamentarian forces became demoralised, melting away at the first opportunity. The Scottish Royalist army in Ulster was badly weakened by desertion before the battle of Lisnagarvey for example.[citation needed]

However, resistance by some of the native Irish Catholic forces, who were faced with land confiscations and suppression of their religion in the event of a Parliamentarian conquest, proved stubborn and protracted. Some units, notably the veteran Ulster Confederate Catholic forces, proved resilient enemies. As a result, the New Model soldiers suffered considerably in the campaign. After victories with few Parliamentary casualties at Drogheda and Wexford in 1649, the fighting became more protracted and casualties began to mount.[citation needed]

At Kilkenny, in March 1650, the town's defenders skilfully beat back numerous Parliamentarian assaults before being forced to surrender.[39] Shortly afterwards, about 2,000 soldiers of the New Model died in abortive assaults against a breach defended by veteran Ulstermen in the siege of Clonmel. These bloody scenes were repeated during the siege of Charlemont Fort later that year. Thousands more died of disease, particularly in the long sieges of Limerick, Waterford and Galway.[citation needed]

The Army was also constantly at risk of attack by Irish guerrillas called tóraithe ("tories" in English), literally meaning "pursuer",[40] who attacked vulnerable garrisons and supply columns. The New Model Army responded to this threat with forced evictions of the civilian population from certain areas and by destroying food supplies. These tactics caused a widespread famine throughout the country from 1650 onwards.[citation needed]

Overall, around 43,000 English soldiers fought in the Parliamentarian army in Ireland between 1649 and 1653, in addition to some 9,000 Irish Protestants.[41] By the end of the campaign in 1653, much of the Army's wages were still in arrears. About 12,000 veterans were awarded land confiscated from Irish Catholics in lieu of pay. Many soldiers sold these land grants to other Protestant settlers, but about 7,500 of them settled in Ireland. They were required to keep their weapons to act as a reserve in case of any future rebellions in the country.[citation needed]

The Army generally performed well when storming fortifications, for example at the siege of Drogheda, but paid a heavy price at Clonmel when Cromwell ordered them to attack a well-defended breach.[42]

Scotland

In 1650, while the campaign in Ireland was still continuing, part of the New Model Army was transferred to Scotland to fight Scottish Covenanters at the start of the Third English Civil War. The Covenanters, who had been allied to the Parliament in the First English Civil War, had now crowned Charles II as King. Despite being outnumbered, Cromwell led the Army to crushing victories over the Scots at the battles of Dunbar and Inverkeithing. Following the Scottish invasion of England led by Charles II, the New Model Army and local militia forces soundly defeated the Royalists at the Battle of Worcester, the last pitched battle of the English Civil Wars.[citation needed]

Interregnum

Part of the New Model Army under George Monck occupied Scotland during the Interregnum. They were kept busy throughout the 1650s by minor Royalist uprisings in the Scottish Highlands and by endemic lawlessness by bandits known as moss-troopers.

In England, the New Model Army was involved in numerous skirmishes with a range of opponents, but these were little more than policing actions. The largest rebellion of the Protectorate took place when the Sealed Knot instigated an insurrection in 1655. This revolt consisted of a series of coordinated uprisings, but only the Penruddock uprising ended in armed conflict, and that was put down by one company of cavalry.

The major foreign entanglement of this period was the Anglo-Spanish War. In 1654, the English Commonwealth declared war on Spain, and regiments of the New Model Army were sent to conquer the Spanish colony of Hispaniola in the Caribbean. They failed in the conflict and sustained heavy casualties from tropical disease. They took over the lightly defended island of Jamaica. The English troops performed better in the European theatre of the war in Flanders. During the Battle of the Dunes (1658), as part of Turenne's army, the red-coats of the New Model Army under the leadership of Sir William Lockhart, Cromwell's ambassador at Paris, astonished both their French allies and Spanish enemies by the stubborn fierceness with which they advanced against a strongly defended sandhill 50 metres (160 ft) high.[43]

After Cromwell died, the Protectorate died a slow death, as did the New Model Army. For a time, in 1659, it appeared that factions of the New Model army forces loyal to different generals might wage war on each other. Regiments garrisoned in Scotland under the command of General Monck were marched to London to ensure the security of the capital prior to the Restoration, without significant opposition from the regiments under other generals, particularly those led by Charles Fleetwood and John Lambert. Following the riots led by Thomas Venner in 1661, which were quelled with the aid of soldiers from Monck's Regiment of Foot and the Regiment of Cuirassiers, the New Model Army was ordered disbanded. However, for their service, both these regiments were, upon the end of the New Model Army, incorporated into the army of Charles II as regiments of Foot Guards and Horse Guards.

Some of the demobilized soldiers and officers of the New Model Army were sent to Portugal, to support the Portuguese Restoration War and help Portugal regain its independence after many decades of Spanish rule. The British brigade, which numbered 3,000, arrived in Portugal in August 1662[44] and proved a decisive factor in winning back Portugal's independence,[45] defeating the Spanish in a major engagement at Ameixial on 8 June 1663, and this forced John of Austria to abandon Évora and retreat across the border with heavy losses.[46] For King Charles II, this was a neat way of both rendering much needed help to the Portuguese House of Braganza, his new in-laws, and at the same time getting rid of demobilized soldiers of the New Model Army and removing them from English territory.

See also

- Robert Blake (admiral) for developments in the Navy at the time

- British military history

Explanatory notes

- ^ Two musketeers for each pikeman was not the agreed mix used throughout Europe, and when in 1658 Cromwell, by then the Lord Protector, sent a contingent of the New Model Army to Flanders to support his French allies under the terms of the Treaty of Paris (1657) he supplied regiments with equal numbers of musketeers and pikemen (Firth 1898, pp. 76–77).

- ^ Under the influence of the Committee of Both Kingdoms which joined English and Scottish Covenantor causes Parliament was inclined to installation of Presbyterianism across England while the NMA tended towards the Independent cause of freedom of religion.

- ^ Full title: "Remonstrance of his Excellency Thomas Lord Fairfax, Lord Generall of the Parliaments Forces. And of the Generall Councell of Officers Held at St. Albans the 16. of November, 1648"

Citations

- ^ a b Ram 1644, p. 15.

- ^ Hutton 2003, pp. 5–6.

- ^ "Trained Bands". BCW Project. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ^ a b Wanklyn 2014, p. 111.

- ^ Young & Holmes 2000, p. 227.

- ^ Cotton 1975, p. 212.

- ^ Wedgwood 1958, pp. 398–399.

- ^ Roberts 2017.

- ^ Royle 2004, p. 319.

- ^ Wanklyn 2014, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Ede-Borrett 2009, pp. 206–207.

- ^ Rogers 1968, p. 207.

- ^ HMSO 1802, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Temple 1986, p. 64.

- ^ Rogers 1968, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Wanklyn 2014, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Temple 1986, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Simpson 2013.

- ^ "Die Veneris, Februarii 28, 1644", Journal of the House of Commons, vol. 4 1644-1646, London, pp. 64–65, 1802, retrieved 28 May 2016 – via British History Online

- ^ Young & Holmes 2000, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Rogers 1968, p. 239.

- ^ Young & Holmes 2000, p. 300.

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 128.

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Firth 1972, p. 70.

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 69.

- ^ Firth 1972, p. 78.

- ^ Young & Holmes 2000, p. 47.

- ^ Firth 1972, p. 91.

- ^ Falls 1969, p. 294.

- ^ Firth 1972, p. 81.

- ^ Roberts 2005, p. 70.

- ^ a b Young & Holmes 2000, p. 231.

- ^ Firth 1972, p. 88.

- ^ Wheeler 1999, p. 151-158.

- ^ Firth 1972, p. 248.

- ^ Firth 1972, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Royle 2004, p. 393.

- ^ O'Siochru 2008, p. 122.

- ^ Joyce 1883, pp. 49–50.

- ^ O'Siochru 2008, p. 206.

- ^ Wheeler 1999, p. 151–158.

- ^ Atkinson 1911, p. 248; Tucker 2009, p. 634.

- ^ Hardacre 1960, pp. 112–125.

- ^ Riley 2014, Back cover.

- ^ Riley 2014.

General sources

- Atkinson, Charles Francis (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 248.

- Barnett, Correlli. Britain and her army, 1509–1970: a military, political and social survey (Lane, Allen, 1970), pp. 79–110.

- Cotton, ANB (1975). "Cromwell and the Self-Denying Ordinance". History. 62 (205): 211–231. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1977.tb02337.x. JSTOR 24411238.

- Ede-Borrett, Stephen (2009). "Some Notes on the Raising and Origins of Colonel John Okey's Regiment of Dragoons, March to June, 1645". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 87 (351): 206–213. JSTOR 44231688.

- Falls, Cyril (1969) [1964]. Great Military Battles. London: Spring Books. ISBN 9780600016526.

- Firth, C. H. (1898). "Royalist and Cromwellian Armies in Flanders, 1657–1662". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. pp. 67–119.

- Firth, C. H. (1972) [1902]. Cromwell's Army: A history of the English soldier during the civil wars, the Commonwealth and the Protectorate (1st ed.). London: Methuen & Co Ltd.

- Hardacre, Paul (1960). "The English Contingent in Portugal, 1662–1668". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 38 (155): 112–125. JSTOR 44228921.

- HMSO (1802). Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 4, 1644–1646. HMSO.

- Hutton, Ronald (2003). The Royalist War Effort 1642–1646. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30540-2.

- Joyce, Patrick Weston (1883) [1800]. The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places. ISBN 9781377939018. OCLC 1129714288. OL 19372548M.

- O'Siochru, Michael (2008). God's Executioner – Oliver Cromwell and the Conquest of Ireland. London: Faber & Faber.

- Ram, Robert (1644). The Souldiers Catechism: Composed for the Parliaments Army, Consisting of Two Parts Wherein are Chiefly Taught: 1. the Justification, 2. the Qualifications of Our Souldiers. Written for the Incouragement and Instruction of All that Have Taken Up Armes in this Cause of God and His People, Especially the Common Souldiers. J. Wright. OL 1678135M.

- Riley, Jonathon P. (2014). The Last Ironsides: The English Expedition to Portugal, 1662-1668. Helion. ISBN 978-1-909982-20-8. OL 28109076M.

- Roberts, Keith (2005). Cromwell's War Machine. Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-094-1.

- Roberts, Stephen K (2017). Surnames beginning 'V' in The Cromwell Association Online Directory of Parliamentarian Army Officers. British History Online.

- Rogers, Colonel H.C.B. (1968). Battles and Generals of the Civil Wars. Seeley Service & Company.

- Royle, Trevor (2004). Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638–1660. Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1.

- Simpson, John (3 May 2013). "The Oxford English Dictionary and its chief word detective". BBC News Magazine. BBC.

- Temple, Robert KG (1986). "The Original Officer List of the New Model Army". Historical Research. 59 (139): 50–77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1986.tb01179.x.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 634. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5. OL 24032712M.

- Wanklyn, Malcolm (2014). "Choosing Officers for the New Model Army, February to April 1645". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 92 (370): 109–125. JSTOR 44232556.

- Wedgwood, C.V. (1958). The King's War, 1641–1647 (1983 ed.). Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-006991-4.

- Wheeler, James Scott (1999). Cromwell in Ireland. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-22550-6.

- Young, Peter; Holmes, Richard (2000). The English Civil War:A Military History of the Three Civil Wars, 1642–1651. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-84022-222-0.

Further reading

- Appleby, David (10 October 2012). "Cromwell's Whelps: the death of the New Model Army". olivercromwell.org. Retrieved 27 October 2018.